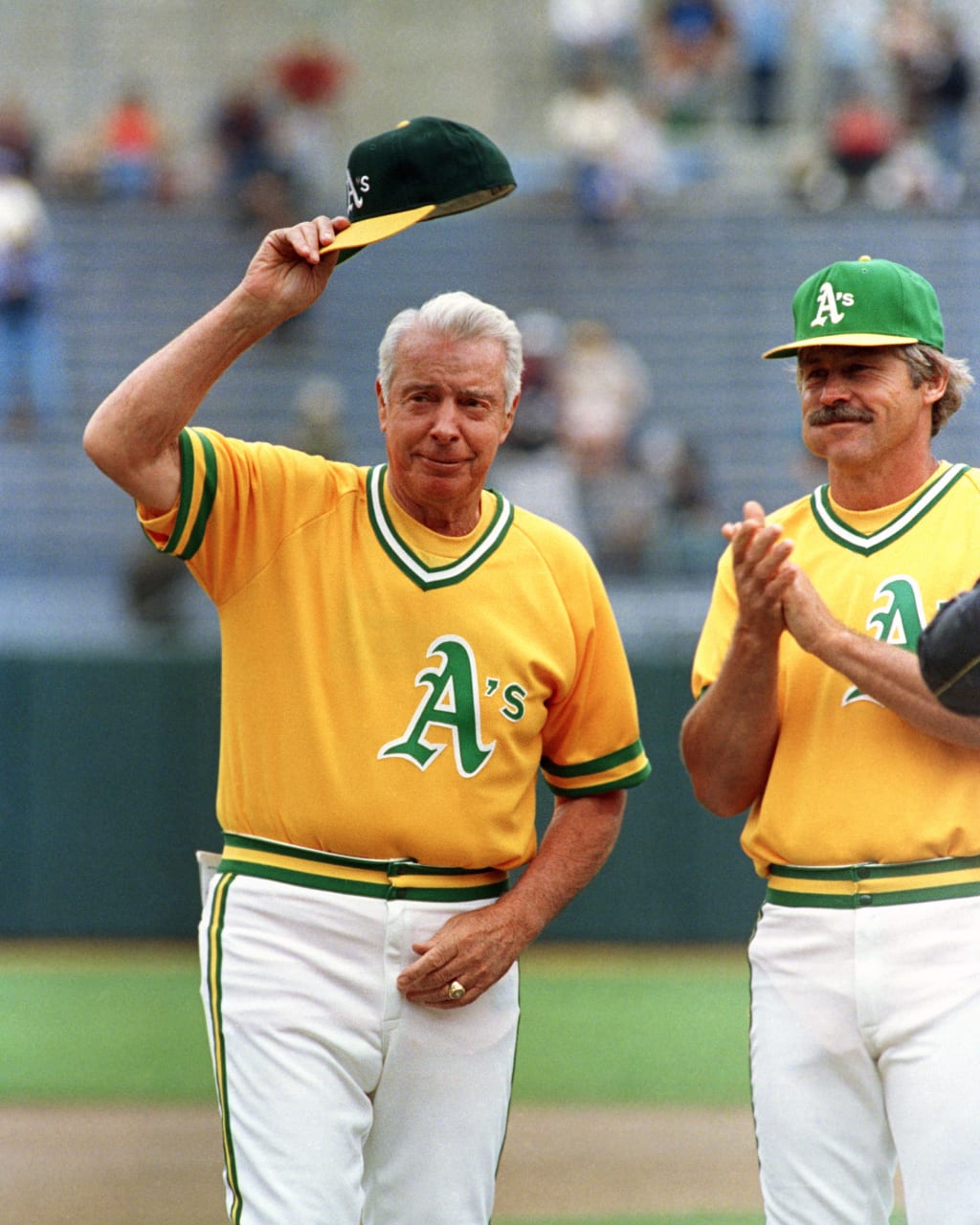

The image does not compute. It ought to come with an Error 404 message. Or maybe an Error 5 message, because that’s the number on the jersey. And while that number and the face of the man wearing it are familiar, nothing else about this picture is recognizable.

That’s Joe DiMaggio, all right. The hair is grayer and the face a little more weathered than in his 56-game-hitting-streak prime, but we’d know that handsome Italian-American mug anywhere. That’s the man who famously said, “I’d like to thank the good Lord for making me a Yankee.”

But good Lord, what is Joe D. wearing here? Why is he in a white hat and gray sleeveless top with that Kelly green undershirt and the California gold trim? Why is he in the outfit that controversially catapulted the sport’s drab duds toward a Technicolor crescendo in the 1970s?

In other words, who the heck Photoshopped the “Yankee Clipper” into an A’s uniform?

Nobody, actually. Though Fans of a Certain Age and those who have scoured every baseball image on the internet might know this, many don’t: In the late 1960s, Joe DiMaggio really was a member of the Oakland A’s.

OK, so he didn’t actually play for the A’s. And that’s why this image catches many of us off-guard. Pictures of Willie Mays with the Mets or Hank Aaron with the Brewers are extremely odd, but at least we know and understand that those great players finished up their legendary careers with those clubs and wearing their more iconic ensembles was not an option.

DiMaggio’s Oakland stint, on the other hand, was a little more clandestine. He was a vice president for two seasons and a coach for one of those two seasons. During that lone season as a coach, in 1968, he didn’t want to work the base lines, which means he spent most of his time in the dugout, which means relatively few fans -- or photographers, for that matter -- saw him rock the green and gold.

But it did happen. And DiMaggio’s brief tenure with the A’s did, much like the uniforms themselves, have some colorful elements to it.

* * * * * * * *

By the spring of 1968, DiMaggio had been away from the game for 16 full seasons. He had announced his retirement at the age of 37 on Dec. 11, 1951, citing various aches and pains.

“When baseball is no longer fun,” he had said, “it’s no longer a game.”

Unlike many other players of his stature -- including his contemporary Ted Williams, who went straight from his Hall of Fame playing career to an executive role with the Red Sox and then a managerial role with the Washington Senators (and there’s another weird uniform for you) -- DiMaggio seemed content to put the game behind him. He had turned down a $100,000 contract to play in 1952. Instead, he was a pre- and postgame host for Yankees games for that season on WPIX, but he ultimately wasn’t comfortable with it and left after a year. He did Spring Training coaching from 1961-67 but never stayed on for the regular season because the job didn’t pay what he deemed himself to be worth.

DiMaggio did magazine ads and television commercials for Buitoni pasta and was briefly married to some woman named Marilyn Monroe. Mostly, though, he was reclusive and elusive.

Until ’68. That’s when A’s owner Charlie Finley evidently made DiMaggio an offer he couldn’t refuse.

The A’s had just moved from Kansas City (where they had perennially vied for last place) to Oakland and were in the very early stages of what would soon become an American League dynasty.

Finley -- a maverick, a meddler and a master promoter -- wanted DiMaggio to be a part of it. And though DiMaggio was associated with a very different team from a very different coast, the fit made geographical sense.

DiMaggio was born, raised and resided in the Bay Area. He had a home on Beach Street in San Francisco, a mere 18 miles from where the A’s would play their home games at Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum. Just as importantly (knowing what we know about DiMaggio), the move made financial sense, too. DiMaggio had retired when he was just two years away from qualifying for Major League Baseball’s maximum pension allowance. This was a way to reach that threshold.

No doubt, Finley, a former insurance salesman, made a pitch every bit as effective as the ones DiMaggio had made for Buitoni and would eventually make for Mr. Coffee. DiMaggio signed a two-year contract to be the A’s executive vice president and consultant.

Just five weeks into that role, however, DiMaggio’s duties expanded. After spending some time among the A’s players at Spring Training, DiMaggio decided to accept an opportunity to be a full-time coach. But he laid down a couple ground rules: He would not coach first or third base, and he reserved the right to turn down banquet invitations.

Many people were understandably shocked that DiMaggio had taken the A’s role in the first place, let alone that he would coach for them. When reporters asked why he hadn’t ever taken a similar job with the Yankees, DiMaggio said he had never formally been offered one. The Yankees countered that DiMaggio had never indicated he was willing to accept such a role.

And so DiMaggio donned the green and gold.

* * * * * * * *

DiMaggio expressed excitement about the opportunity to help the next generation of players.

“I have become attached to these kids,” he told reporters shortly before Opening Day. “I have never been around a group so eager to learn.”

Those “kids” included future Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson, as well as Bert Campaneris, Joe Rudi, Sal Bando, Gene Tenace and Rick Monday -- the young position player core that would soon power the A’s up the standings.

(Incidentally, a light-hitting infielder who was also of Italian-American descent would have a cup of coffee with the ’68 A’s and therefore briefly work with DiMaggio. His name was Tony La Russa.)

DiMaggio is said to have had an instant -- and lasting -- effect via the power of observation. As the story goes, DiMaggio was walking around Oakland Coliseum in advance of the ’68 season when he noticed that the views of home plate were obscured in portions of the upper deck. So officials moved the infield further from the backstop.

To this day, the A’s home has the largest foul territory in the big leagues.

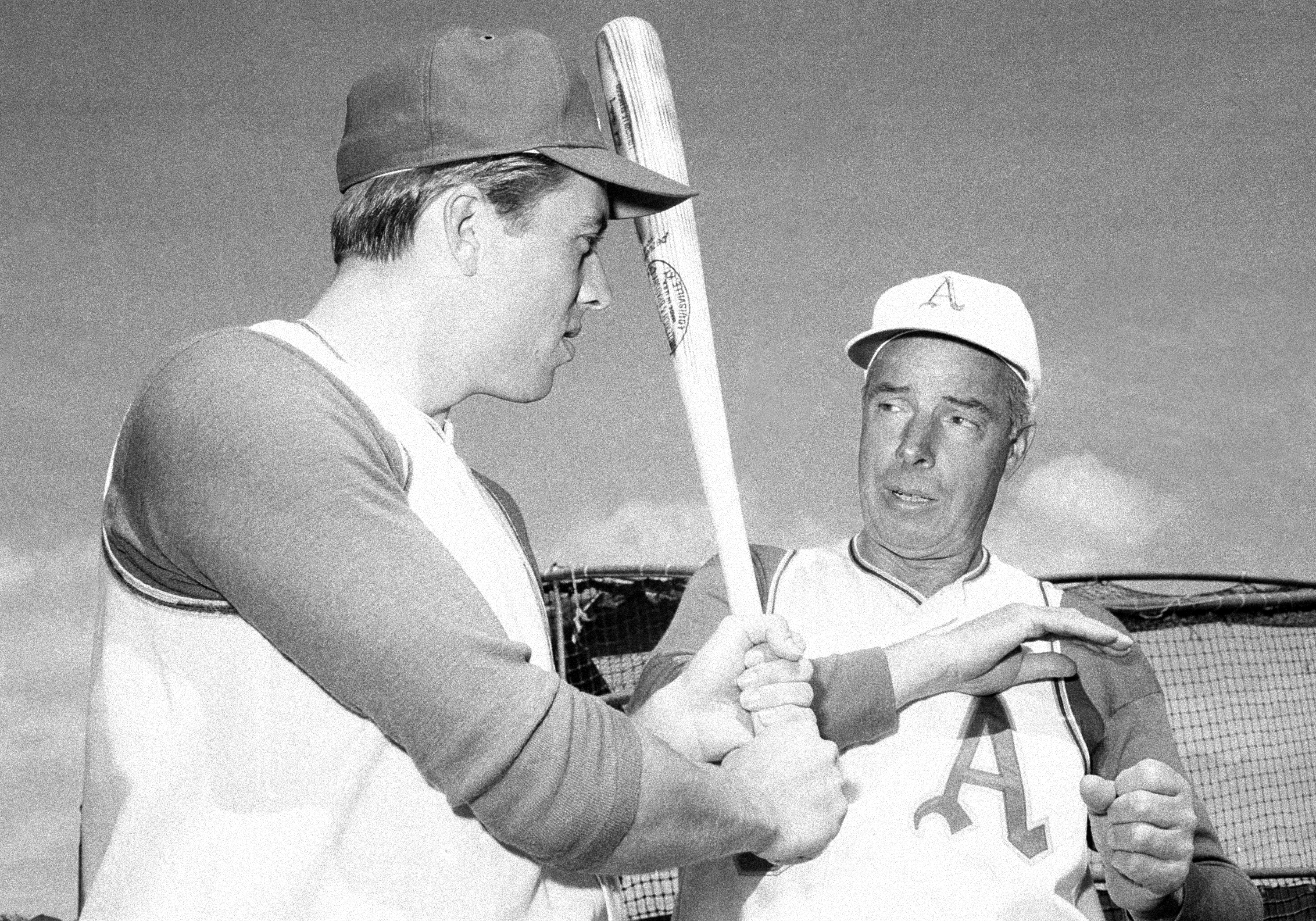

DiMaggio also made his mark with his teaching. He was the one who trained Rudi, a shortstop-turned-left fielder, how to properly handle balls hit over his head. The two worked on it for about half an hour before every game in ’68.

“Joe took me under his wing,” Rudi once told Baseball Digest. “That’s a play where you have to turn your back to the ball, find the wall, then turn back around and find the ball. It was so hard to learn. I was, like, 50 feet off-line when I started out.”

By the 1972 World Series, Rudi had mastered it. He fought the sun to make a terrific back-handed grab of a Denis Menke line drive to preserve the A’s win in Game 2 against the Reds.

“I kept thinking back to DiMaggio, and the thousands of balls I practiced on," Rudi said. "I learned from the best."

DiMaggio was also instrumental in Bando, who had hit .192 in 47 games a year earlier, making the change that unlocked his potential.

“I was getting jammed on everything,” Bando once said. “Then Joe D. told me to close up my stance.”

Bando improved to hit a more respectable .251 with nine homers and 25 doubles in ’68, then received AL MVP votes in seven of the following eight seasons, finishing second in the voting in 1971.

DiMaggio also developed a strong relationship with Jackson.

“Reggie is still green as grass,” DiMaggio told a sportswriter in ’68. “We’ve just got to bring his talents to the surface. They’re all there, no question.”

DiMaggio encouraged Jackson to put down the thin bats he’d used at Arizona State and go to the plate with heavier lumber. Jackson struck out an MLB-high 171 times that season (this must have offended the eye of DiMaggio, who struck out just 369 times in his entire career), but he hit 29 home runs. And if one particularly great photo is any indication, DiMaggio didn’t just serve him baseball instruction but also postgame lasagna.

(Years later, DiMaggio, who was throwing out a ceremonial first pitch, visited Jackson in the Yankees’ clubhouse prior to Game 6 of the 1977 World Series against the Dodgers and told him what a great ballplayer he’d become. Jackson backed up the compliment by hitting three home runs that night in the Yankees’ clincher, forever cementing himself as “Mr. October.”)

The ’68 season -- in which the A’s won 82 games for their first winning record since 1952 in Philadelphia -- was DiMaggio’s only one in uniform. He fulfilled full-time front-office duties in ’69, and then, with his pension fully vested, went back to golfing and fishing (and, soon enough, the Mr. Coffee pitches). He left the A’s on good terms and was often invited back to throw out a first pitch and to be cheered by the Oakland fans. For a decent fee, of course.

Thankfully, we’ve got a few surviving photos to document that brief and unusual period in which DiMaggio wore another uniform. The Yankee Clipper never became the A’s skipper, but he did make an impact in Oakland.