"Well, Doby has returned since I wrote you before. He looks fine," Effa Manley, the owner of the Negro Leagues' Newark Eagles, wrote to Eagles shortstop (and future big leaguer) Monte Irvin about his double-play partner at the keystone, Larry Doby, on Jan. 28, 1946. Doby had recently returned from the war effort, and he would go on to help the Eagles win the Negro World Series championship later that year before making his Major League debut as the first Black player in the American League in 1947.

But Manley wasn't writing to Irvin about Doby's baseball abilities. Rather, she was writing about his skills on the basketball court.

"Doby played basketball with The [O]range Triangles Saturday night," her note continued. "He is some basketball player. Mr. Manley said we will have enough Eagles on the baseball team to have a basketball team."

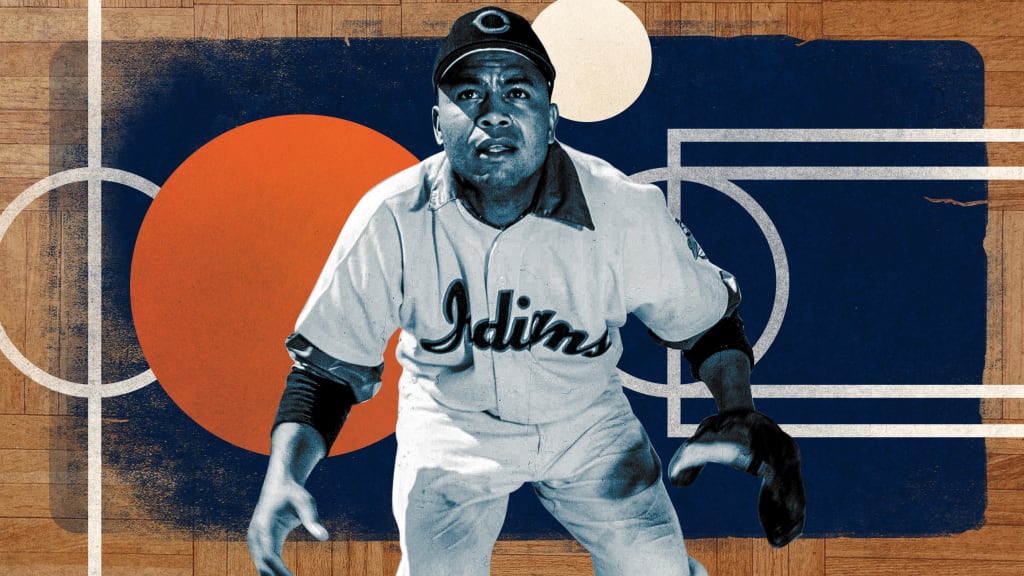

It wasn't just the Manleys who thought that Doby looked good on the court, though. Doby was a three-sport star in high school and even accepted a scholarship to then-college basketball powerhouse Long Island University, where legendary head coach Clair Bee was coaching. While the nascent war effort led Doby to attend Virginia Union University instead, it's clear that basketball was far from some ballplayer's dalliance.

In fact, according to Luke Epplin, author of "Our Team," about the 1948 World Series-winning Cleveland Indians, Doby's best sport may not have been baseball at all.

"The way that he was talked about in high school by the local paper, which is the Paterson News, they were higher on him as a basketball player, and even as a football player, than they were about him as a baseball player," Epplin said in a recent phone call with MLB.com. "It almost seemed like baseball was his third-best sport, really."

That's echoed by someone who played with Doby in high school: New Jersey legend Al Kachadurian, who lined up alongside Doby on the high school football and baseball teams. Epplin spoke to Kachadurian while writing "Our Team," and Kachadurian remembered Doby as being a standout basketball player -- one who could have possibly changed the way the game was played at the time.

"If you asked me what his best sport was, I'd say basketball," Kachadurian told Epplin. "Remember, it was an era when they had set plays. They'd go this way, and the guy would take a two-hand set shot. And [Doby] was the only one who would not do that. He would get through anybody. They didn't have to have a play for him. He was pure speed. He was the only one who had moves. No one could touch him."

In fact, if not for Jackie Robinson's emergence at this time, opening up the possibility of a future in the Major Leagues, Doby may have committed himself to basketball. It was reported in The Paterson (N.J.) News that Doby had an offer to play for the New York Renaissance -- the first Black-owned, all-Black pro basketball team that played its games in Harlem -- instead of lining up for the Triangles.

But there was one reason that Doby turned down the offer:

"Reason: If Branch Rickey calls," the paper read, "he wants to be in a position to answer."

"Doby doesn't fully commit to becoming a professional baseball player until Jackie Robinson is signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers Minor League organization," Epplin noted. "That's when he really sees there could be a future that is a little bit brighter than just scraping by in the Negro Leagues, which he was a little skeptical of. It seemed like he wanted to get an education and become a physical education instructor, and so basketball was his means of doing that."

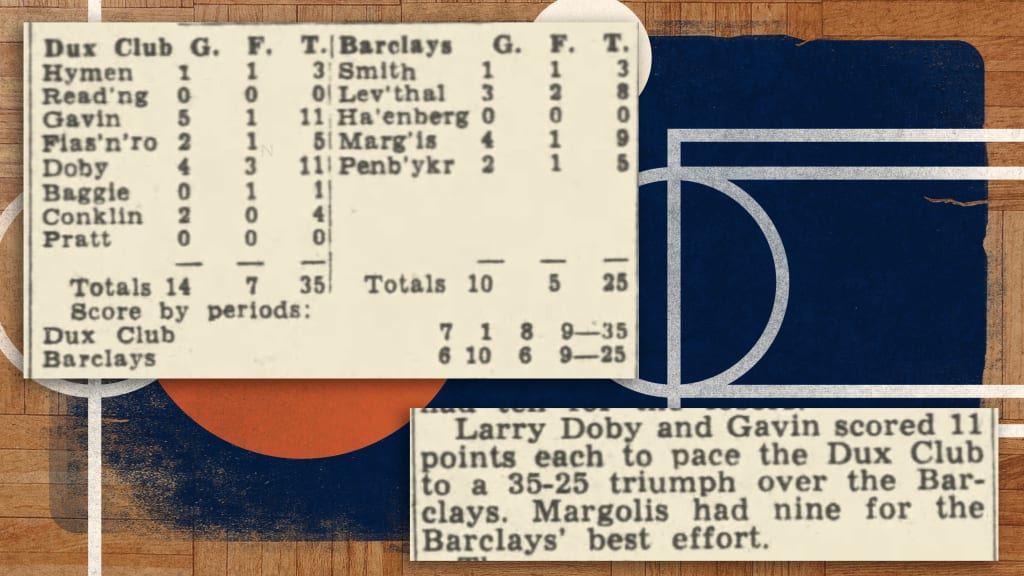

Though Doby's 1946 basketball season would end soon after Manley's note -- and he would go on to hit .354 for the Newark Eagles that summer, making his Major League debut with Cleveland the year after -- he wasn't done on the basketball court. After going 5-for-32 in brief playing time for Cleveland in the summer of '47 as the first Black player in the American League, he returned to New Jersey that winter and joined up with the Paterson Crescents of the American Basketball League, an early pro league that was a precursor to the NBA.

"You can't separate Doby's decision to play basketball in 1947 away from the context in which he's making that decision," Epplin explained. "Context of course, is that he's a tenuous Major Leaguer. He might be sent back either to the Minors or the Negro Leagues. He is not necessarily making a tremendous amount of money at that time. He doesn't have a firm grasp in the Indians roster. Back then, I would say 99 percent of the people not named Bill Veeck think that he's not going to make the roster. So, it doesn't surprise me that he would take that opportunity during the offseason to play basketball to supplement his earnings or to keep his foot into that realm."

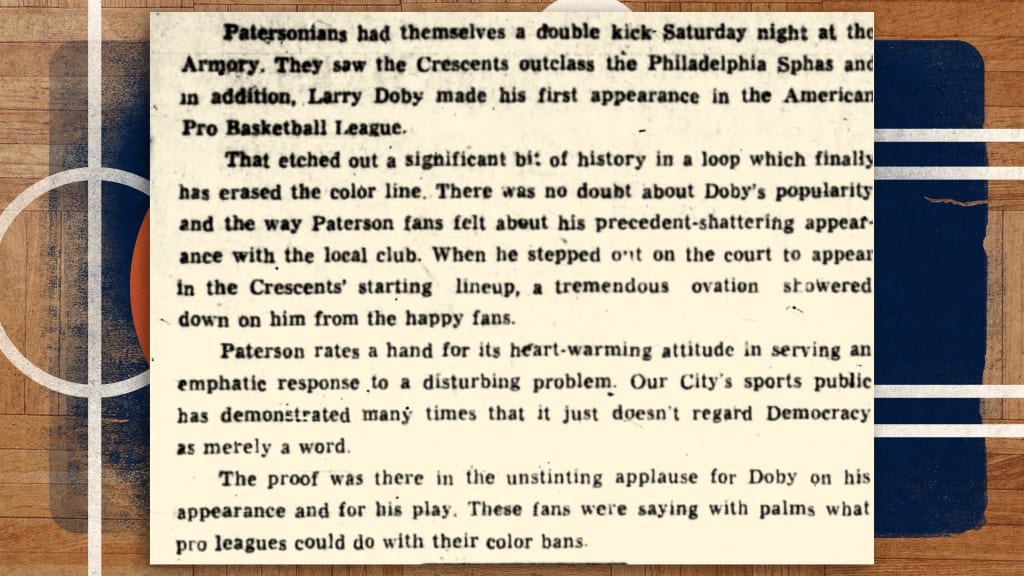

When Doby first took the court with the Paterson Crescents on Jan. 3, 1948, he made history there, too. Yes, the first Black player in the American League also became the first Black player in the ABL.

Joe Gootter wrote in the Paterson News that Doby's debut "etched out a significant bit of history in a loop which finally has erased the color line. There was no doubt about Doby's popularity and the way Paterson fans felt about his precedent-shattering appearance with the local club. When he stepped out on the court to appear in the Crescents' starting lineup, a tremendous ovation showered down on him from the happy fans."

After entering to the thunderous applause, Doby played the entire first quarter and the first eight minutes of the second before ever taking a seat on the bench.

Never known for his scoring prowess -- Doby finished the game with three points -- Gootter reported that "Larry made an impressive debut. Considering that he was making his first start in a circuit which ranks with the toughest pro competition, he did a workmanlike job in the 22 minutes he was in there," adding that Doby "displayed flawless ball-handling, court savvy, and good team play."

Doby would only play seven more games for the Crescents, finishing with 15 total points in his brief pro basketball career. But more important was the continued integration of sports leagues across the United States that was taking place.

"The proof was in the unstinting applause for Doby on his appearance and play," Gootter wrote on Doby's debut. "These fans were saying with palms what pro leagues could do with their color bans."

We know the story from there: Doby would put together a Hall of Fame baseball career, playing 13 years in the American League while hitting .283 with 253 home runs -- leading the league in dingers three times -- and earning election to seven All-Star Games.

But he wasn't quite done with basketball. After serving as the White Sox manager in 1978, Doby returned to New Jersey. When fellow Eastside High School alum, Paterson resident and lifelong friend Joe Taub bought the then-New Jersey Nets with the "Secaucus Seven" in 1979, he soon hired Doby as the Director of Community Relations.

This wasn't some ceremonial and cushy job where Doby would be expected to show up to a handful of games and make a few speeches, though: Doby was committed to giving back to the community that had supported him through his life.

"Larry and Joe Taub shared a passion for philanthropy," Rick Laughland, author of "A History of the Nets: From Teaneck to Brooklyn," and an upcoming book on the history of the Subway Series, said in a recent phone call. "They founded the Taub-Doby youth sports competition. It created opportunities for students to have scholastic as well as a sports scholarship opportunity. They maintained that [the players] had to be well-rounded, they had to maintain a certain grade level."

According to former long-time Nets executive, Lou Terminello, Doby would regularly go out into the area himself, too, giving over 400 speaking engagements at local youth centers in Newark, Paterson and beyond. Doby helped raise funds for local museums and even tried to mentor Micheal Ray Richardson, the NBA player who struggled with drug and addiction problems during his career.

"Larry took him under his wing and tried to mentor him and coach him," Laughland said. "He did everything in his power to keep him on the straight and narrow."

Despite his fame and prestige, despite the historic achievements he had made, Doby was committed to his work and the future for these young athletes rather than wanting to live in the past. There's a reason he was recently honored with a Congressional Gold Medal, after all.

"Really, when he held a title, whether it was in baseball or with the Nets," Laughland said, "he went above and beyond the job description."