A version of this story originally ran in February 2022.

Billy Joel’s world tour had reached Japan, and that gave Larry Doby Jr. -- a member of Joel’s road crew -- an opportunity to explore an oft-forgotten piece of his famous father’s baseball history.

So on a break between concerts on that day in 1995, Doby Jr. and some fellow roadies boarded a bullet train bound for Nagoya, where the Chunichi Dragons still played in the open-air stadium with the all-dirt infield that the elder Larry Doby and his friend Don Newcombe had briefly called home more than 30 years earlier.

“When [people in Nagoya] found out who I was,” Doby Jr. recalled with a smile, “they were bowing to me.”

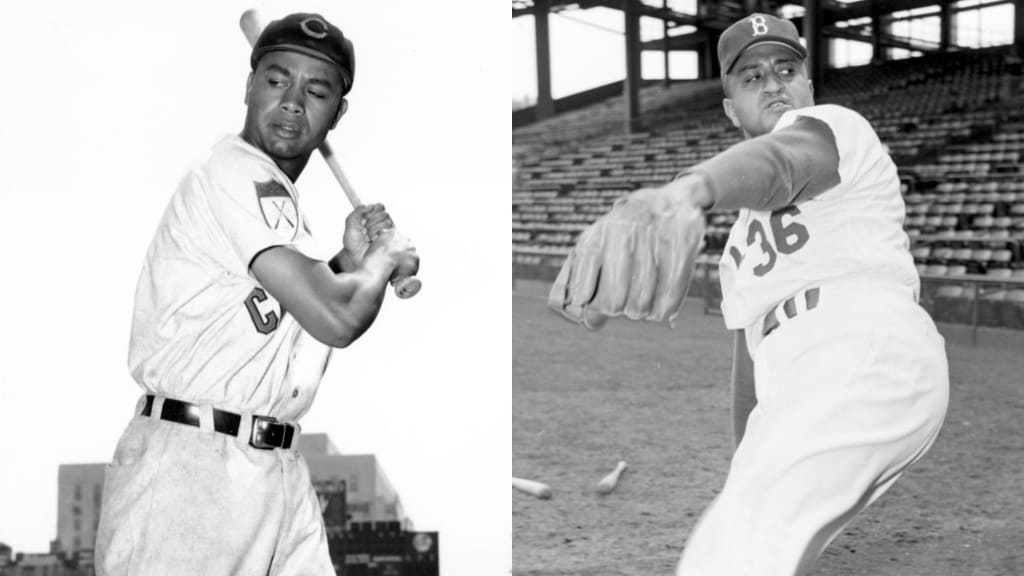

In the United States, we know Doby as the Hall of Famer who broke the American League color barrier, and we know Newcombe as both the first pitcher to win the Cy Young Award and the first Black pitcher to win 20 games in a season and start in the World Series.

The single season Doby and Newcombe played for the Dragons -- with Newcombe primarily playing at first base, not pitcher -- is a mostly forgotten footnote to the great careers of these trailblazers.

In Japan, however, they remember Doby and Newcombe as trailblazers of a different sort.

“My dad and Mr. Newcombe are still held in really high regard in Japan,” Doby Jr. said, “probably because they were the first ex-Major Leaguers to go over there and play.”

Doby and Newcombe were both on their last legs as players when they signed on with Chunichi in 1962. Doby was nearly three years removed from his final Major League game, while Newcombe had spent the previous season pitching for Spokane in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League.

But in Chunichi, these recently retired stars were revered and celebrated as potential season saviors for a Dragons team in need of a boost.

The arrival overseas of Doby and Newcombe was both a continuation of a historical trend of Black players influencing the Japanese game and the beginning of a new trend of established Major Leaguers extending or reviving their careers in Nippon Professional Baseball.

A 1934 barnstorming tour of Japan that featured Hall of Famers Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Lefty Gomez, Charlie Gehringer, Connie Mack and others is often credited with helping to launch professional baseball in the Land of the Rising Sun. After efforts to start a professional league in Japan earlier in the century had fallen flat, that tour, in which Major League luminaries competed against some of Japan’s best players from the high school and collegiate ranks, sparked enough interest to help initiate the Japan Professional Baseball League (JPBL) -- the forebearer to the present-day Nippon Professional Baseball -- in 1936.

But the Negro Leagues also played a part in baseball forming a professional toehold in Japan.

In 1927 -- and again a few seasons later -- a Black club known as the Philadelphia Royal Giants visited Japan and other parts of Asia on a goodwill tour. During the first tour, players like Biz Mackey (who hit the very first home run at Jingu Stadium, which was constructed in 1926 and still stands today) and Rap Dixon wowed with their prodigious power, and the Royal Giants’ speed and strong, accurate throws also left lasting, inspiring impressions on the Japanese athletes. Some Negro League researchers have suggested that the Japanese game more closely resembles the Negro Leagues -- with an emphasis on teamwork, small ball and finesse pitching -- than the American or National Leagues.

And whereas the white players on their later tours would often run up the score on their inferior Japanese opponents, the Black players were said to approach their games with respect and sportsmanship.

“Other countries rejected baseball because the visiting professionals left fledgling players disillusioned with the game through defeat,” Japanese baseball historian Kazuo Sayama once wrote. “We were lucky enough to have the chance to neutralize the shock. … The Royal Giants’ visits were the shock absorber.”

As historian and author Bill Staples Jr., a member of the board of directors for the Nisei Baseball Research Project, wrote in an email, the story of how baseball came to be such a popular and important sport in Japan can’t be told without mention of the influence of those early Black players.

“There’s no doubt that the tours of the white Major Leaguers did a lot to increase the fans’ demand for pro baseball as a form of paid entertainment,” Staples wrote. “But I argue that it was the tours of the Nikkei [Americans of Japanese ancestry] and Negro Leaguers who made the greatest impact on the supply -- the quality of the players that Japan had to put on the field. … The pre-war tours of the Nikkei and Negro Leaguers helped the Japanese elevate their level of play and maintain their passion for the game when they needed it most -- and thus, the Japanese Baseball League began in 1936.”

Ten years before Jackie Robinson’s 1946 arrival to the Dodgers’ Montreal affiliate began the integration of affiliated Major League Baseball, the nascent JPBL had its first Black player in the form of a pitcher named Jimmy Bonner.

Bonner had made a name for himself with the San Francisco Colored Giants, Oakland Black Sox and Berkeley Grays, catching the attention of Harry Kono, a West Coast businessman and agent for the Dai Tokyo Baseball Club of the JPBL. Kono recruited Bonner to play for Dai Tokyo.

“Dashing Bonner Releases an Amazing Crossfire from his Iron Arm,” read one (translated) caption from a Japanese newspaper at that time.

Alas, in his one month with the club, Bonner and his “iron arm” struggled with a tighter strike zone and different ball. He didn’t last long in Japan, but he set a precedent for an American-born player journeying across the Pacific to play professionally.

World War II, of course, changed everything -- both for the JPBL (which became NPB in 1949) and Japanese-American relations, in general. Professional baseball in Japan became a more isolated endeavor for a long while.

On April 28, 1952, however, the Treaty of San Francisco, which formally ended Japan’s role as an imperial power and ended the Allied nations' post-war occupation of the country, went into effect. That very day, third baseman John Britton and pitcher Jimmie Newberry -- two former Negro League stars then under the contractual control of Bill Veeck’s St. Louis Browns -- were lent to a Hankyu Braves team in need of talent in what was billed an “Independence Day gesture.”

“As Japan gains its independence as the world’s newest democracy, we of the St. Louis Browns are happy to aid the mutual relations between the United States and Japan by sending two of our American ballplayers to the Japanese pro leagues,” Veeck said in a statement to reporters. “In Japan, as well as in America, baseball is the national game, and we feel this gesture on the part of American baseball will go a long way towards cementing good relations with the Japanese.”

The following year, two more former Negro League stars -- Larry Raines and Jonas Gaines -- would also join Hankyu, which finished in second place in the Pacific League in 1953.

The goodwill gesture had been a success, and a bridge had been built.

But when Britton, Newberry, Raines and Gaines were sent across the Pacific, none of them had played in the American or National Leagues (of the four, only Raines, who played briefly for Cleveland in 1957-58, would do so). It was not until the early 1960s that a process we are now familiar with -- established Major Leaguers extending their professional careers by venturing over to Japan -- was initiated.

And it began with two particularly big names in Black baseball history.

Two Japanese baseball representatives and their interpreter walk into a bar.

That’s not the setup to a joke; it’s the setup to the story of how Newcombe and Doby changed Nippon Professional Baseball forever.

In 1962, Newcombe was no longer pitching but, rather, running a liquor store and cocktail lounge in Newark, N.J. One day, the three visitors cited above visited to gauge his interest in playing in Japan … primarily as a first baseman, not a pitcher.

The 1956 NL champion Dodgers team that included Newcombe had visited Japan after the World Series. So he was familiar with the country. And though the Dragons unsuccessfully tried to recruit the likes of Robin Roberts and Billy Martin, Newcombe accepted their offer.

“When I agreed to go,” Newcombe once told Doby biographer Joseph Thomas Moore, “and when the publicity came out about it, I got a call from Pierre Salinger.”

As in, the future U.S. Senator and ABC News correspondent and then-press secretary for President John F. Kennedy. Newcombe and Salinger had golfed together in the past.

Just 17 years after the United States dropped atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the U.S. was in the process of establishing positive relations with the newly democratic nation.

Baseball was a shared love, a crucial common ground.

“[Salinger] asked me to come to the White House for an interview,” Newcombe continued. “When I got to the White House, Salinger told me that, in effect, I would be representing President Kennedy and the United States. He said we had established pretty good relationships with the Japanese people, and through baseball, we could establish further relationships and even open up the possibility of other American players going to Japan.”

Newcombe was not given any duties to perform by the president’s office, but he was asked to comport himself respectfully. He was up to that task, and he wanted to bring along a friend. He urged the representatives from the Dragons to offer a contract to Doby, too.

“[Doby] didn’t want to play because of his ankle, and he didn’t think he could get in shape,” Newcombe recalled. “I told him, ‘Larry, here’s a chance to make some money, and you won’t have to work hard. It seems to me to be easy baseball to play. If you can get in any kind of shape, you can hit the ball.’”

Doby, who had served as a scout for the White Sox and was in the process of purchasing a Newark liquor store and bar of his own, was on board. His son was only 4 years old at the time -- yet, all these years later, he remembers it well.

“My mother took him to the airport,” Doby Jr. said. “It was raining, and I’ll never forget it. He left, and we didn’t see him for months.”

Doby went solo overseas, living alone in a Nagoya hotel room. Newcombe brought his wife and young son and lived in a house in the suburbs.

“The club has done more than we anticipated,” Newcombe told an Associated Press reporter early in his tenure. “My wife has been provided with everything from diaper pins to an electric washer-dryer combination.”

In Japan, these tall Black men (Doby stood 6-foot-1, Newcombe 6-foot-4) certainly stood out in the crowd as “gaijins,” or foreigners.

“At the time, Newcombe and Doby were two of 21 foreign players in Japan,” Staples wrote. "Others were mostly white and Nikkei players. They were the only African-Americans. The presence of all foreign players in NPB was controversial -- still not well-received by everyone in Japan.”

But the Dragons’ Hawaiian-born coach Wally Yonamine, who selflessly retired as a player to make room for Doby (NPB limited the number of foreign players on each roster), saw the big picture.

“Even if they don’t help our club, they will help our players,” he said at the time. “In the end, Japanese baseball will benefit.”

Doby and Newcombe attended a few receptions and were invited to meet Prime Minister Hayato Ikeda during their time in Japan.

Mostly, though, their business was baseball.

Newcombe was an important pitcher in MLB, but he had also swung the bat well in his career. He batted .300 or better in four seasons in his limited opportunities and even hit seven homers with nine doubles for the Dodgers in his All-Star 1955 season.

So while his move to first base was unorthodox, it wasn’t completely out of the blue. In his first 11 at-bats, he hit a homer, a double and two singles. He was an instant spark for the Dragons, who were in last place in the Central League when he arrived and gradually began to move up the standings.

“Newk may well be considered as playing the role of a stimulant for his team,” a Japanese radio commentator was quoted as saying.

All told, Newcombe played 81 games, batting .262 with 12 homers and 23 doubles. He only pitched four innings.

Doby arrived 10 days after Newcombe because he was tying up loose ends with his liquor store purchase. And Doby was rustier, having not played the previous three seasons. The transition was difficult for him.

“The first month or so, it was tough, just getting into shape,” Doby later told Moore. “But I enjoyed it there. I felt relaxed. I had Newk’s friendship. The Japanese people treated us with a lot of respect and fine hospitality. I knew I was at the end of my career, so I took the games one at a time.”

Over time, Doby’s power shone through. Though he would bat only .225 in 72 games, his 10 homers left a lasting impression, as writer Kiyoshi Nakagawa marveled in his 1976 book “40 Years of Chunichi Dragons.”

“Even today,” Nakagawa wrote, “there are still quite a few fans who remember the sound of Doby’s bat cutting the air and his special swing.”

Ultimately, Newcombe and Doby made a modest impact on the results (the Dragons wound up finishing a respectable 70-60-3, good for third place in NPB’s Central League) but a big impact at the gates, with attendance rising from about 5,000 per game to 20,000.

And Doby and Newcombe themselves were impacted by the experience.

“My dad brought back a ton of kimonos and those wooden shoes with the heels on them [geta],” Doby Jr. recalled. “He brought back these geisha dolls, a ton of that stuff.”

Doby also began to call the family German shepherd “Gondo,” after Dragons pitcher Hiroshi Gondo.

“I don’t know if [the name] was in honor of him or if he didn’t like the guy,” Doby Jr. said with a laugh. “But he was a pretty good pitcher. I’m assuming, because he didn’t say anything bad about him, that it was in honor of him.”

Doby would recall that he received letters from several of his Japanese teammates for years after that 1962 season.

“He always said his biggest mistake was that he didn’t go back,” Doby Jr. said.

Doby was lonely in Japan with his family back in New Jersey. In 1963, he asked for more money to bring his family along, but he and the Dragons could not come to an agreement.

Newcombe, meanwhile, had possibly, in Staples’ words, “scouted himself out of a job,” as he helped the Dragons sign more American players like Jim Marshall. NPB rules allowed for only three foreigners per roster. The team invited him to return as a coach, but he declined.

So their time in Nagoya proved to be just a one-year experiment, and it was the final playing opportunity for both Doby and Newcombe.

Back in the States, Newcombe battled alcoholism, then went on to become the Dodgers’ director of community affairs in the 1970s -- delivering speeches on the pitfalls of drinking and serving as an inspiration by helping others. He passed away in 2019. Doby went on to become MLB’s second Black manager with the White Sox in 1978. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame in '98 and passed in 2003.

In Japan, Newcombe and Doby set a template that would be followed by many other established Major Leaguers in the ensuing years.

Three-time All-Star George Altman went on to a long and productive NPB tenure that included time with the Lotte Orions and the Hanshin Tigers. Longtime infielder Clete Boyer spent several seasons in Japan and even roomed with all-time Japanese home run leader Sadaharu Oh. Three-time Gold Glove winner Willie Davis spent two seasons in Japan before returning to the States to finish his Major League career with the Angels. Warren Cromartie left MLB in his prime to go to NPB, where he was MVP of the Central League in 1989. Tuffy Rhodes' 464 home runs rank 13th all-time in NPB.

That’s just a smattering of the influence American players have had on NPB.

It’s a tradition that even made it to the movies. In the 1992 comedy “Mr. Baseball,” Tom Selleck plays fictional Yankees first baseman Jack Elliot, who is traded to an NPB team during Spring Training and forced to adjust to a new league and landscape.

Elliot’s new team? The Chunichi Dragons.

So Newk and Doby set a precedent for players, both real and imagined. And that’s why they are known as trailblazers, both here and abroad.