The patches decorate the desk in Jerry Reuss’ home office. Each one is a midsummer memento, featuring the logo of every MLB All-Star Game from the last 40-plus years.

“I love looking at them,” says Reuss, the two-time All-Star pitcher whose career touched four different decades from 1969 to 1990. “It’s a nice thing to collect. Every year, I look forward to the new one being available.”

It all began at the end of the 1980 season, when Reuss -- the winning pitcher in that year’s Midsummer Classic -- took the All-Star patch off his Dodgers uniform and put it away for safekeeping.

And come to think of it, a lot of things began with that ’80 All-Star Game at Dodger Stadium.

That was the year the All-Star Game began to morph from a game to a gala, from a one-day event to what has become a weeklong experience. It marked the debut of the mammoth scoreboard video screens that are now ubiquitous across sports. It was the first year an All-Star appetizer -- in this case, the Dodgers Old-Timers Game – was added to the schedule. And between the steak luncheon for the stars, the pregame Disneyland presentation and the effort put into the program and pins and other branded wares, the Dodgers left no doubt that the All-Star Game would never be the same.

As the event returns to Dodger Stadium for the first time in 42 years, those involved with the 1980 All-Star Game look back at it as an eventful exhibition, memorable not so much for the National League’s 4-2 victory but for the template it set.

“This was a major breakthrough,” says Fred Claire, then-vice president of public relations and promotions for the Dodgers. “The whole scope and significance of the All-Star Game changed.”

“The whole idea was to make this a festival”

Sometime in 1979, Claire called Willie Sanchez, general manager of the Dodgers’ Triple-A affiliate in Albuquerque, with a job offer. He wanted Sanchez to be the club’s official All-Star Game administrator, devoting himself to planning and marketing the event.

“We have an opportunity to do something that’s never been done,” Claire told Sanchez.

What Claire meant was that the Dodgers could expand the scope and seriousness of the All-Star Game and turn it into a true summer spectacle.

Oh, and they could turn a profit, too.

“The All-Star Game had always cost ballclubs money,” Sanchez says. “We wanted to make money.”

In the past, most of the game’s marketing elements had been handled by the league. Claire and team owner Peter O’Malley wanted the Dodgers to run the show. And they wanted it to be a bigger presentation than it had ever previously been.

“We wanted it to be the gold standard,” says O’Malley.

Adds Sanchez: “The whole idea was to make this a festival, where every day there is something going on.”

Sanchez’s first bit of inspiration came when he and wife went to a movie distributed by Paramount Pictures. Before the opening credits, Sanchez saw Paramount’s famous logo -- the animation of 22 stars arranging themselves in a semi-circle pattern around a mountaintop -- and envisioned a circle of stars for what became the All-Star mark.

“There were 51 stars around the logo, because it was the 51st game,” O’Malley says. “And it worked. It was a really catchy, attractive logo.”

Another of Sanchez’s ideas was to include a tear slip on the All-Star Game ballots distributed at every ballpark that people could mail in -- along with a $2.50 payment -- to receive the collector’s program. No team had ever marketed the magazine like that before.

“We sold about 150,000 of those things,” Sanchez recalls.

The program’s cover -- featuring an anonymous batter whose swing was modeled after that of former Dodgers outfielder Bill Bucker -- was also printed on posters that were put up for sale. And the star-struck logo was printed on ash trays, cocktail jiggers, pins, etc.

As for the schedule, with the All-Star Game slated for Tuesday, July 8, the Dodgers arranged their annual Old-Timers’ Day -- a tradition that had begun in 1971 -- for Sunday, July 6, to make it part of the festivities. The retirement ceremony for Duke Snider’s No. 4 was held at that event, in which Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale and other past Dodgers greats participated.

The Dodgers also decided to open the doors of Dodger Stadium to fans, free of charge, for the All-Star workout on Monday -- a precursor to what has become a ticketed workout day that features the Home Run Derby, which debuted in 1985. And in another first, a lavish luncheon was planned for the All-Stars to attend on the day of the game at Lawry’s, an iconic L.A. steakhouse in Beverly Hills.

“That was the highlight of everything, the All-Star luncheon,” Reuss says. “Once everybody cleared out, I saw all these All-Star glasses and mugs and coffee cups laying around. I found a cardboard box and grabbed as many as I could. I gave many of them way but still have some on a shelf.”

But the biggest innovation of all -- quite literally -- was the gigantic, 875-square-foot screen installed in Dodger Stadium’s left-field scoreboard area.

“It changed the whole spectator experience”

Prior to the 1980 All-Star Game, dot matrix displays using incandescent light bulbs were the backbone of outdoor digital signage.

But Japan-based Mitsubishi Electric aimed to change that by developing a cathode-ray tube video board with color fidelity that would revolutionize sporting events. It was called Diamond Vision, and Mikio Matsubayashi, who was the North American distributor for the product, invited Peter O’Malley to travel to Japan to check it out in late 1979.

“They wanted a stadium and an event to showcase it,” Claire recalls. “We had just the place.”

O’Malley remembers being blown away by what he saw on that trip to Japan.

“The color was extraordinary, even in the daytime,” he says. “That’s what got our attention.”

Mitsubishi wanted $1 million to install and maintain the first Diamond Vision board at Dodger Stadium. Claire recalls O’Malley negotiating the cost down to just a dollar, as the Dodgers were offering themselves as the proving ground for the technology. O’Malley would only confirm that it was more than a dollar and less than $1 million.

Once the negotiating was done, the only question was whether Mitsubishi could have the board ready in time for the All-Star Game. But Diamond Vision’s debut was as important to the company as it was to the team.

“It was a photo finish,” O’Malley says, “but they got it done. So many people involved in stadiums around the world came to see it.”

That first video board changed everything -- not just for the 1980 All-Star Game but sporting and entertainment events, in general. From instant replays to close-ups to blooper reels to the “Kiss Cam,” video boards are now as integral to the ballpark as hot dogs and beer.

“It gave teams an opportunity to have a higher level of entertainment and engagement with the fans,” says Paul Kalil, who spent 25 years producing video screen shows for the Dodgers and is now CEO of Van Wagner Sports & Entertainment Productions. “It evolved to become such a part of the game that it changed the whole spectator experience.

Mitsubishi had to rush to ready the first Diamond Vision board for its big reveal.

“We were very cognizant that this thing could take over the entire game,” Kalil says. “It’s big, it’s bright, especially at night. We had to turn the brightness down about 50 percent in the early days. But it was definitely well-received.”

Built at a cost of $3.5 million, the first Diamond Vision was a 20-foot tall and 28-foot wide rectangle and replaced a hexagon-shaped dot matrix message board. By today’s standards, that’s a puny presentation. For the sake of comparison, L.A.’s Sofi Stadium now has the largest video board in sports, with a 70,000-square-foot oval whose smallest panel is 20 feet tall.

But in 1980, the first Diamond Vision board, which would remain in Dodger Stadium until 2012, was game-changing stuff.

“It was great for the fans,” says Fred Lynn, who started for the AL in center field that night. “You see the game larger than life, especially if you missed a play because you were out getting a hot dog or something.”

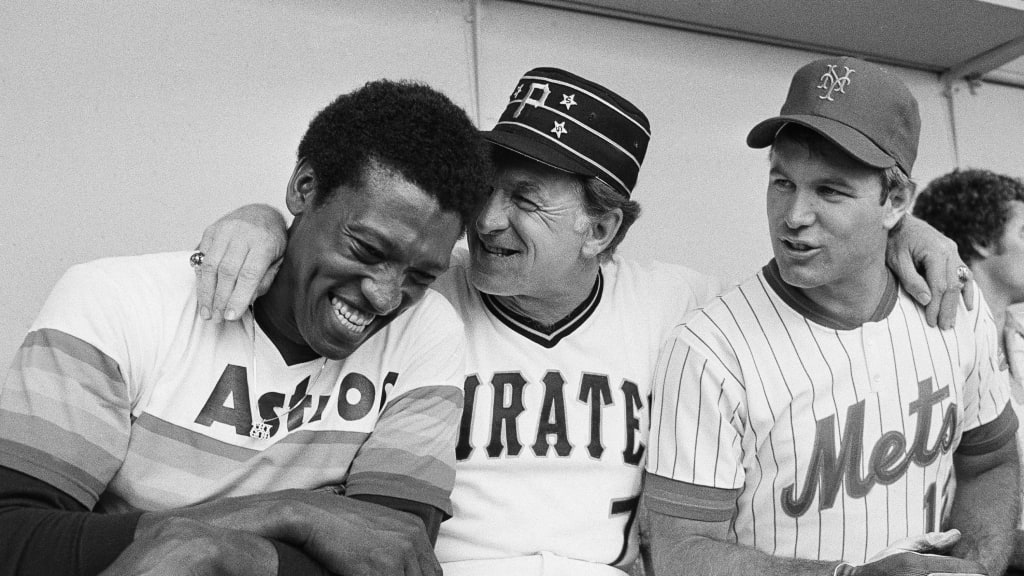

Jerry Reuss remembers coming into the game in the sixth inning and talking to second baseman Phil Garner at the mound. He pointed to the screen.

“Isn’t that the best TV you’ve ever seen?” Reuss asked.

“I’d have to buy a new house,” Garner replied, “just to put that thing in there.”

“Think about this,” Reuss added. “There are 75 million people watching this game wondering what the hell we’re talking about. They’re probably thinking we’re giving each other a scouting report. But we’re talking about the television!”

“We had an opportunity to do something great”

Reuss might have inflated the numbers a bit, but the ’80 All-Star Game did attract a large audience -- a sell-out crowd of 56,088 (including former President Gerald Ford) in the stadium and 36 million TV viewers, making it the second-most-watched All-Star Game ever. The broadcast crews were All-Star teams, too -- Howard Cosell, Keith Jackson, Al Michaels, Don Drysdale and Bob Uecker on ABC, and Vin Scully and Brent Musberger on the radio call.

The pregame presentation had stars of a different sort -- Disney stars. Disneyland sent hundreds of its costumed characters up from Anaheim for an on-field celebration prior to first pitch that also included eight marching bands and dozens of Boy Scouts. Fireworks were set off from Elysian Park, and a fire broke out in the dry summer grass.

“One of the reporters asked me if that was part of the program,” Claire recalls. “I said, ‘No, we’re not that good.’”

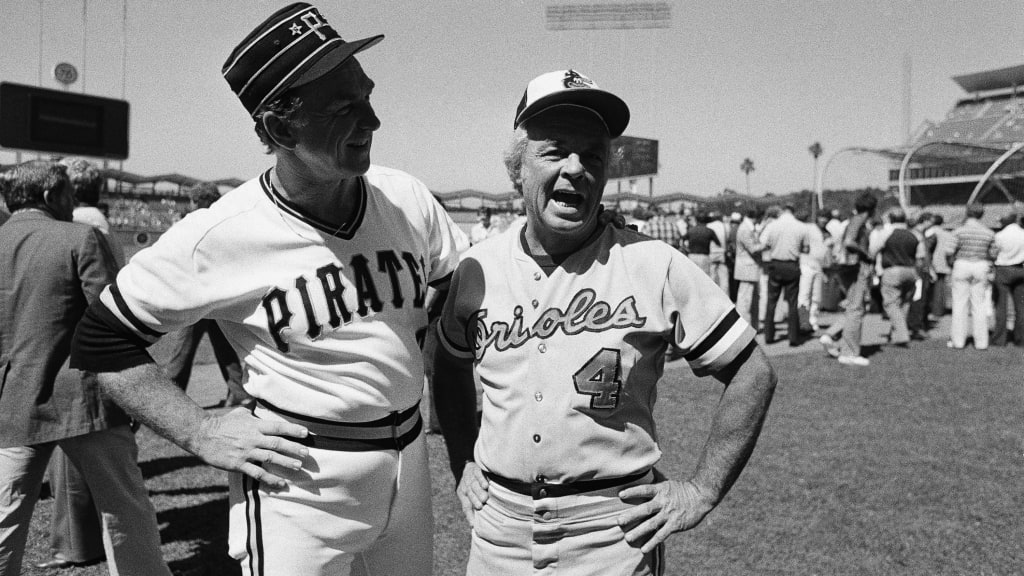

The fire was quickly extinguished, and so were many of the batters, with Dodger Stadium’s early evening shadows preventing them from picking up on pitches. AL starter Steve Stone, in the midst of a 25-win Cy Young season with the Orioles, worked three perfect innings.

“That was one of the crowning achievements in my entire career,” Stone says. “I always loved Dodger Stadium, because it was a park built for pitching. The major thing for me was being able to bring my parents to see the game in the stands. And then to throw three perfect innings, which hadn’t been done [in an All-Star Game] in 16 years and won’t be done again, because they’ll never let starters go three innings in an All-Star Game now.”

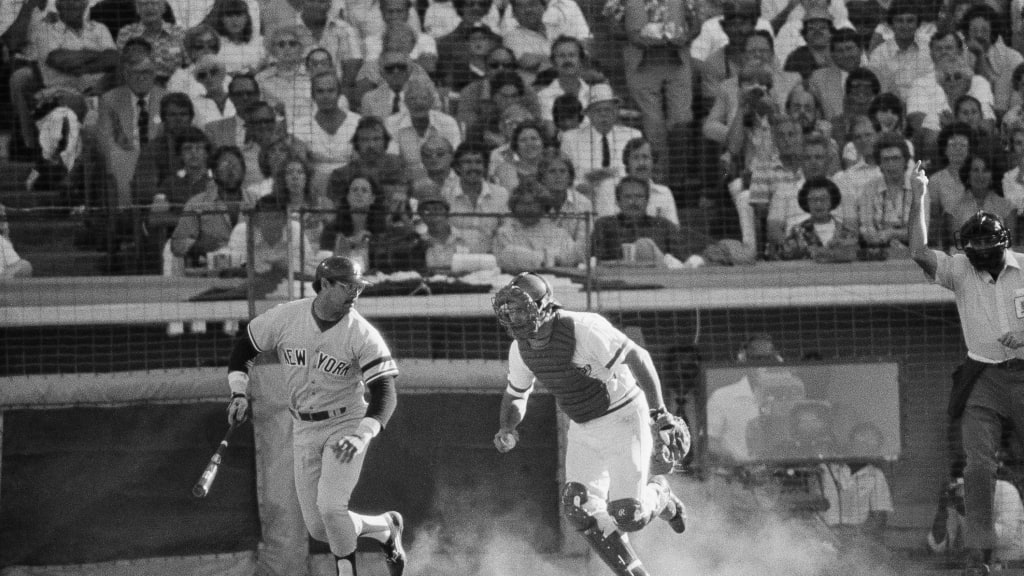

Lynn, who grew up in the L.A. suburbs, broke the scoreless tie with a two-run homer off Dodgers pitcher Bob Welch in the fifth inning.

“I went to USC, right down the street, so I had a lot of family and friends there,” Lynn says. “The last time I had played at Dodger Stadium was a USC-Dodgers exhibition at the end of Spring Training. So it was cool to come back. I hooked one down the right-field line into those low seats, just enough to get it out of the ballpark.

But the NL, which was riding an eight-game All-Star winning streak, broke up the AL’s no-hit bid with a Ken Griffey Sr. homer off Tommy John in the bottom of the fifth. And in the sixth, the NL took over when five consecutive batters reached base against John on four singles and an error, allowing two runs to score.

The NL won, 4-2, and would extend its winning streak to 11 with victories in 1981 and ’82, before Lynn’s grand slam in the ’83 game at Chicago’s Comiskey Park finally turned the tide.

“It was not an exhibition,” Lynn says. “We were out there to win.”

The biggest winners in 1980, though, were the Dodgers. They showed off their jewel of a facility in innovative ways and set a framework that future All-Star events would follow.

“It was part of the philosophy of the Dodgers and the O’Malley leadership to promote the game,” Claire says. “It was the presentation of the game, where each game had meaning. And when you had the All-Star Game, there was the realization that we had an opportunity to do something great.”

Forty two years later, the All-Star Game finally returns to Dodger Stadium. There will be a three-day oceanfront beach party at Santa Monica Pier and a baseball and softball festival at the Los Angeles Convention Center and the L.A. Live campus. The Futures Game, the amateur Draft and a celebrity softball game will be held as part of the festivities. And of course, the Home Run Derby and the game itself.

The five-day extravaganza will make the ’80 event look quaint, by comparison. But the idea of turning a nine-inning exhibition into a more ambitious celebration of the sport dates back to the only previous All-Star Game at Dodger Stadium.

And Reuss has the patches to prove it.

“Everybody wants their All-Star Game to be bigger and better than the team that hosted it the previous year,” Reuss says. “So I’m excited to see what the Dodgers do this time.”