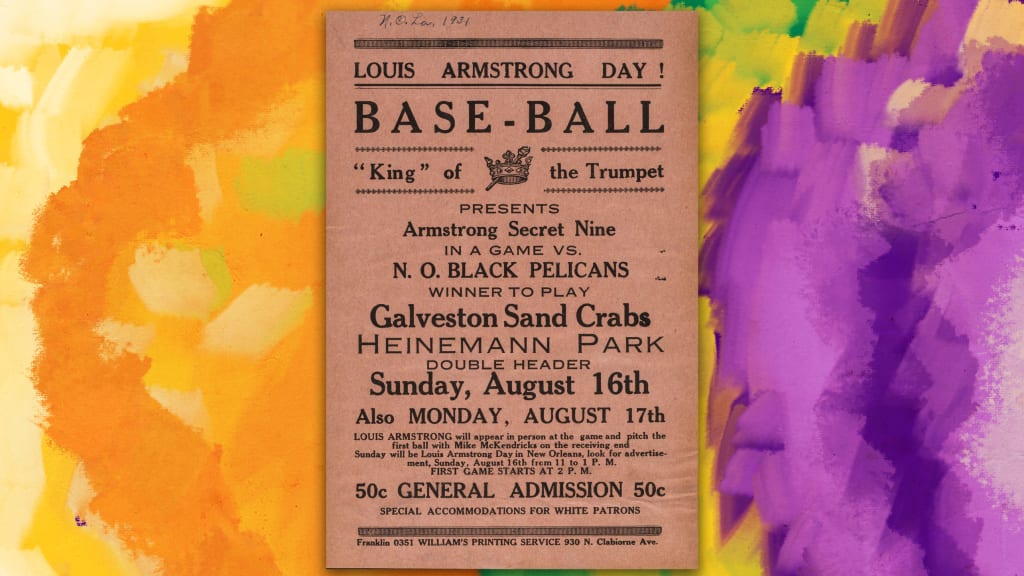

Aug. 16, 1931, was designated "Louis Armstrong Day," a holiday created for -- and perhaps made by -- Louis Armstrong on his return to his hometown of New Orleans. There would be music, there would be entertainment and there would be baseball with Armstrong's very own team, the Secret 9, taking the field. Only 30 years old, Armstrong was already a jazz legend who had forever changed the art form.

"He's the biggest selling artist in the recording industry and he had just made his first film," Ricky Riccardi, the Director of Research Collections at the Louis Armstrong House Museum in Queens, N.Y., said in a recent Zoom call. "In the '20s, he had been making what they called race records, but now he was making pop records aimed at the general community, and he was selling more records than any of the white artists. And so there was actually a bidding war for his contracts. He's hitting this new height of popularity."

There was another reason that made it the perfect time for Armstrong to make a triumphant return to New Orleans for the first time in nine years. His manager, Johnny Collins, went back on a deal with a club in Harlem that was owned by the mob. That led to a gangster going into Armstrong's dressing room before a show in Chicago and holding him at gunpoint, strongly suggesting that the musician head to New York.

"We have to stay away from Chicago, we have to stay away from New York, it's too hot," Collins said. "Let's go on tour."

Armstrong would soon take off for Europe, but first, he was back in his hometown for the summer, playing shows at The Suburban Gardens.

"He's packing the place every night," Riccardi said. "The only place that they can find for him was a whites-only establishment, but it was on the levee, and it had open windows and so the way Armstrong would tell it, every night 4,000, 5,000 African-Americans would be outside hearing him."

The hero of New Orleans, who had emerged from its jazz scene and forever changed the art form thanks to his ear for harmony and melody and daring lead lines, was now to be honored. And there was no better way to do it than with baseball -- a deep love of Armstrong's.

"He loved playing baseball," Riccardi said. "I mean, for the world's greatest trumpet player to name that as his number two hobby, it says a lot."

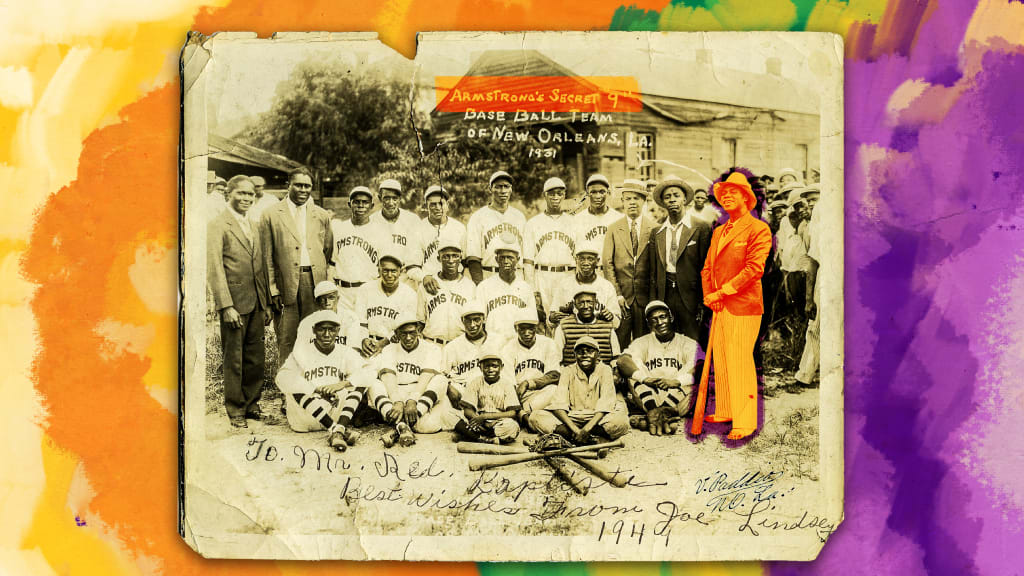

So, Armstrong found a local team -- likely made up of members of the Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club, a New Orleans "parade krewe and community organization," and Mardi Gras institution -- and outfitted them in the finest uniforms possible. These were crisp, white brand-new togs with Armstrong's name across the front and numbers on the back. At a time when some professional Black teams were wearing hand-me-downs -- the San Francisco Sea Lions wore uniforms with bear cubs on the front because they got the jerseys from a team known as the Cubs -- Armstrong’s threads stood out. They were the kind of thing made to play some serious baseball in and so, that's just what they did.

They played throughout the city that summer, but it all culminated on "Louis Armstrong Day." The Secret Nine took to Heinemann Park, home to the New Orleans Pelicans and, occasionally, the New Orleans Black Pelicans. The latter was their opponent on the holiday.

A comedy act took the field to warm up the crowd and then Armstrong came out to throw the first pitch. When the game was ready to start, Armstrong went back to the stands to take in the action, where he could only watch as his Secret Nine were demolished by the professional club.

"I think [The Secret Nine] was a glorified sandlot team," Riccardi said. "Louis was in New Orleans for the summer of 1931 and he was friends with most of them and thought it would be cute, and so he paid for uniforms, gave them a name. ... They got their brains kicked out."

Or, as a newspaper wrote that day, Armstrong's team "couldn't make the grade against 'Lucky' Welsh's Black Pelicans" as they dropped the game, 4-0.

There was a talent discrepancy for sure, but that may not have been the only reason. Found in one of Armstrong's notebooks years later was this entry:

“Of course they lost, but I still say they wouldn't have been beaten so badly if they hadn't been too proudly to slide into the plate," Armstrong wrote. "Just because they had on their first baseball suits, and brand new ones at that, but it was all in fun, and a good time was had by all I know. I had myself a ball."

But just who was on the Secret Nine is actually still a secret to this day. In fact, it took until 2019 for the first person to be identified in the team photo. That's when researcher Ryan Whirty -- along with New Orleans' International House Hotel -- dove deep into history and discovered that Edward “Kid” Brown Sr., a local boxer of some renown and a likely Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club member, was in the photo. He's in the back row, third from the left.

That he was identified at all is thanks to Edward Brown Jr. -- the "Kid's" son -- who saw the team photo in the newspaper and remembered that his family used to have their own copy.

“I realized that this was the same picture that we had before [Hurricane] Betsy destroyed it in 1965," Brown Jr. told Whirty.

The overlap between jazz and baseball has long been known, and it was quite common for band leaders to put together games during tour stops. Count Basie had a team, and Cab Calloway had a team with their own uniforms who would play against semi-pro teams and host charity events. Duke Ellington hosted pickup games while he was on the road. The practice is still going on today: Though he's not a jazz musician, Jack White regularly plays pickup games while on tour and has his own uniforms.

"Baseball was the sport of jazz you can say, and in the Big Band era, when jazz gets as close as it'll ever get to become an America's pop music -- that's the swing era -- all the popular bands were big bands, and most of them are 15, 16 pieces. And so there's your baseball team," Riccardi said. "So the musicians themselves would spend their days sometimes playing in Central Park, or Count Basie's band would challenge Jimmy Lunsford's band. There was no league and no rules or anything, but it was definitely a way that they passed the time and they loved it."

Fortunately, thanks to the archives at the Armstrong House Museum, we know that Armstrong's attachment with the sport only grew deeper as he got older. Though he had already played at a White Sox game as a member of the King Oliver band in Chicago, Armstrong would become a big Dodgers fan -- thanks in part to Jackie Robinson. Inspired by a trip to Italy in 1949, Armstrong began making collages of things that interested him. He would then "piece them together and make a little story of my own ..."

So, in 1952, he assembled a collage of Robinson, scotch taping a variety of photos and newspapers together to tell the tale of the first Black player in the Major Leagues.

Armstrong would soon befriend a number of the Dodgers' Black stars, including Junior Gilliam and Don Newcombe. He remained a fan of the team even after they left New York. The proof is on an audiotape in the museum's archives where Armstrong brags to his manager, Joe Glaser, that the Dodgers defeated Glaser's White Sox in the '59 World Series.

He kept a box at Yankee Stadium -- though he often couldn't attend without being swarmed by autograph seekers. Comedian and baseball fanatic Billy Crystal's first game at Yankee Stadium was actually in Armstrong's seats. Thanks to his family's music connections, Crystal was there when Mantle hit one of the most majestic home runs of his career.

Later, when the Mets arrived and moved into Shea Stadium, a short eight-block walk from Armstrong's house, the legendary cornet player swapped allegiances. He was once interviewed in the late '60s or early '70s, and Armstrong was watching the Mets on the TV while listening to the Yankees on the radio at the same time. He befriended Mets players and "would show up and take out Cleon Jones and people after the games [for a] hang at Louis' house."

But perhaps the strangest story -- even more bizarre than a baseball team whose lineup is still a mystery 90 years later -- is how Armstrong wound up with Yogi Berra's catcher's mask during the 1957 World Series.

Armstrong was touring in Argentina at the time and the fans couldn't get enough of him.

"The first night the fans mobbed him, there's almost a riot on the streets," Riccardi said. "And the one thing that petrified Louis more than anything else was if a fan touched his lips. If his lips got damaged, he couldn't play the trumpet. People were trying to touch his lips, they were saying 'touch your lips, touch your lips!'"

So, he did the only thing he could do: He called Glaser and made a simple request: "Get me one of Yogi Berra's catcher's masks."

"Glaser apparently made this happen," Riccardi said with a grin. "It's October '57 while the Yankees are in the World Series against the Braves!"