SEATTLE -- Behind every big league manager, there is an elite team of baseball nerds called the analytics department.

And in Seattle, manager Scott Servais isn’t afraid of the data they bring to the table.

“I'm really open to the information,” Servais said. “How can we use the data to help coach?”

Ever since Michael Lewis published Moneyball, his best-selling account of the Oakland A’s use of advanced metrics to overcome the disadvantages of a small market, clubs have adopted increasingly data-oriented approaches to fielding competitive teams.

At the front office level, the result is executive suites full of Ivy League number-crunchers. On the field, the game has seen increased employment of infield shifts, hard-throwing relievers and patient but powerful hitters.

The prevalence of data has also shaped Servais’ approach to coaching, allowing him to be more evidence-based. For example, if a specific pitch isn’t coming out right, Servais can point to precise data about that pitch’s spin rate and release point from a TrackMan data-capturing system.

“We really try to get evidence-based stuff instead of, 'Ah, it doesn't look right,’” Servais said. “That's kind of the old school. They didn't have all the data we have now.”

Throughout the regular season, Servais said he routinely receives information about defensive alignments, pitch-framing and pitch selection in addition to heat maps. Although the skipper admitted he’s not familiar with specific formulas and the ins-and-outs of all the data, he said the baseball operations group does a good job explaining how their information can impact the players’ performance.

Servais and his staff are in charge of relaying that information to the players, who almost never come face-to-face with members of the analytics team. They must do so without overloading the athletes.

Servais acknowledged that analytics has swayed many of his baseball opinions, including ideas the former big league catcher used to have about pitch framing. He wishes there had been more information available when he was playing since he’s certain the data would have made him a better player.

“I think a lot of people that have been exposed to analytics get frustrated by it -- maybe they don't understand it,” Servais said. “They look at it as a threat. It's not a threat. It should help make you a better coach.”

Here are the people behind the numbers for the Mariners.

Jesse Smith, Director of Baseball Analytics

Education: Cognitive Psychology major, University of Chicago

Smith joined the Mariners seven years ago as an intern -- before they had an analytics department.

“Good timing on my part,” Smith said. “The Mariners were behind the curve at that point, I would say.”

Smith is now starting his third year as director of the department. He’s faced with the task of ensuring his team balances short-term projects -- like answering queries from coaches or making preparations for an upcoming series -- with long-term projects, when a member of his team might develop a new tool the other 29 clubs don’t have. His group also weighs in on trades, signings and extensions.

As the leader of a big league analytics department, Smith fields multiple emails a day from people looking for jobs from a talent pool generally made up of computer science, math and statistics students.

“'Do I want to make four times as much money and have a lower quality of life, or do I want to go for it in baseball?’ is usually what we run into,” Smith said. “It's awesome to work in an industry where people really want to be there because you get your pick of the litter of really smart young people who are willing to do an internship when they otherwise wouldn't have to.”

Smith said he likes odd backgrounds that remind him of his own. During undergrad, he did statistics research in a lab studying negotiation at the University of Chicago. The plan was to pursue a PhD or Master’s and continue doing research, but a friend asked him to start a concert-promoting company in Portland.

Two years later, he realized he didn’t have the same passion for music as he had for baseball. Smith grew up a Moneyball A’s fan in the Bay Area but moved to Seattle as a 9-year-old. When he moved back to Seattle after finishing up with the concert company, he got an interview with the Mariners.

And now he’s built a team of analysts that didn’t exist when he joined the organization.

Joel Firman, Manager of Analytics

Education: Economics major, Washington State University

Area of focus: Pitch evaluation

Firman knew he wanted to get into baseball analytics very early in his academic career.

“I took an Economics course and it really spoke to me in terms of how I think about baseball is how people are thinking about real life,” Firman said. “I enjoyed that and started to do some research on my own.”

Firman began learning different computer science tools for his baseball research and also took online classes and consulted his father, a software developer.

After sending his research findings to teams across the country, Firman eventually landed internships with the Yankees and then the Mariners before getting promoted to full-time analyst and eventually a management role in the department at the end of last season. The move was a return home for the Washington native.

“I’m incredibly lucky in that regard,” Firman said. “I moved as far away as a I possibly could have, just about, to work for the Yankees and then to come back home was crazy. I was, beyond doubt, the biggest Mariners fan I had ever met as a kid.”

John Choiniere, Baseball Analyst

Education: Chemistry major, Carleton College; PhD in Chemistry, University of Washington

Area of focus: Catching

Most people working in baseball analytics don’t have their own family or a post-graduate degree, but Choiniere has two kids and a Chemistry PhD. He was a working chemist -- more specifically a mass-spectrometrist -- who started working in baseball so he could keep his family in Seattle.

“By the time you get to the PhD level in chemistry, you get really hyper-focused on one specific field,” Choiniere said. “When that job was no longer working, there literally just weren't any other openings in the Seattle area for someone who did what I did.”

Rather than uproot his family, Choiniere began working for Baseball Prospectus’ stats team. His only other baseball experience was a grad-school hobby: using analytical tools he learned as a PhD to help sportswriters at SB Nation’s Beyond the Box Score.

A year later, Choiniere applied for an internship with the Mariners. He was the only intern who could call himself a doctor or a father.

“There was definitely a pay cut going to the intern level, and it's hard to be an intern at age 32,” Choiniere said. “Fortunately my wife was very supportive of this whole goal and has always made a lot more money than me. So that worked out just fine.”

Choiniere was promoted to full-time analyst after his year as an intern. Though he understands he doesn’t fit the typical mold of someone working in his field, he’s made his life’s work as a family-man baseball analyst.

“I have a wife and two kids, and the stereotype of these sorts of jobs is that you're here 80 hours a week and always on call,” Choiniere said. “I've been blown away by how supportive everyone's been in terms of keeping a work-life balance. I don't know that I would get that in another organization.”

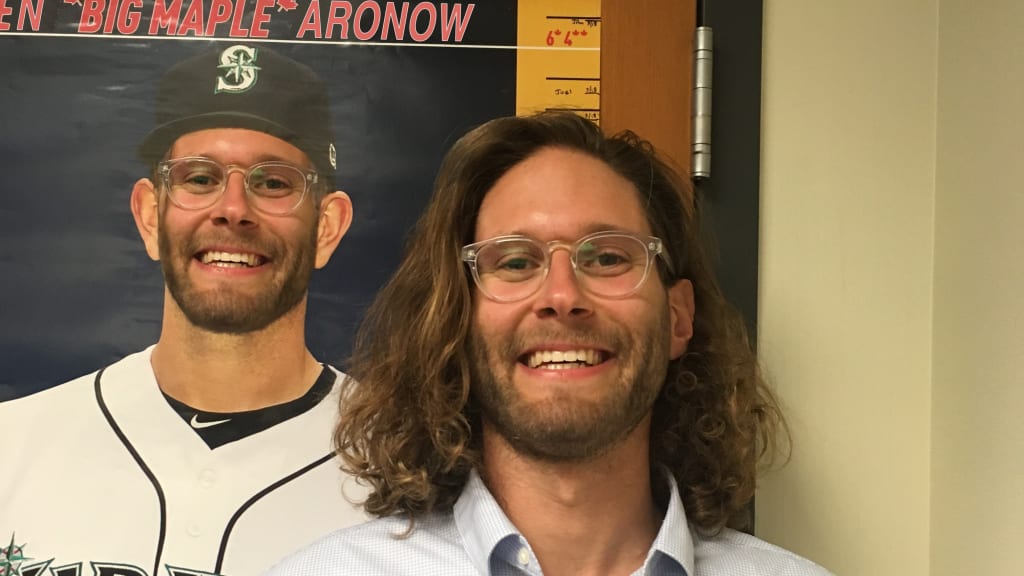

Ben Aronow, Baseball Operations Analyst

Education: Applied Mathematics and Economics major, Brown University; Master’s in Management Science and Engineering, Stanford

Area of focus: Offensive approach

Ivy League graduates commonly end up working lucrative consulting jobs or joining promising tech startups. Aronow has done both. He likes baseball better.

Aronow took a job as a management consultant working with pharmaceutical companies after he finished up at Brown, but he hated that job and quit after nine months. Next, he began working as a project manager for a software startup, an experience he said was valuable, but he wasn’t interested in staying.

“I wanted to be a little bit more intellectually stimulated in what I was doing, so I ended up applying for grad school,” Aronow said. “At the same time, I thought I'd try applying for baseball analytics internships just because it's something I had been interested in for a long time — kind of expecting I wouldn't get one because there aren't that many and a lot of people want to do it.”

Aronow landed an internship with the Yankees. He also got into Stanford. So he did both.

Like Firman, Aronow ended up making a lateral move to the Mariners. He could have returned to the Yankees, but having grown up in New York, he chose to apply to some teams on the West Coast and has found a home in Seattle.

“I just liked the people I met here. I had a good feel for the city,” Aronow said. “In an hour you could be skiing, you could be rock-climbing, you could be backpacking. So that's pretty exciting to me.”

Forrest Diamond, Baseball Operations Analyst

Education: Neuroscience and Philosophy major, Boston University

Area of focus: Holistic evaluation

Diamond, 27, was an analyst with the New Balance footwear company when he began applying to baseball operations internships. The oldest and most experienced of Seattle’s three interns last year, he had a long path of odd jobs before landing with the Mariners.

Before turning his attention to baseball full-time, Diamond worked as a night manager at an IT lab, an analyst for the now-defunct Fall Experimental Football League and an intern for TrackMan -- whose technology tracks data about pitches and batted balls across baseball.

Diamond was using data to help New Balance predict which athletes were worth sponsoring. Now, he works with the Mariners to predict how baseball players will perform.

The path to getting there wasn’t easy. Diamond applied to about 20 teams, landing first-round interviews with about half of them and ending up with an offer to join the Mariners as an intern before being promoted to a full-time analyst position this year.

“I was a consultant for New Balance, so yeah, it was a pay cut, but I really like what I'm doing here and it was worth it,” he said. “I do want to push back a little on the idea that we're not paid that much. I think they pay pretty well for interns, it's just that a lot of my coworkers could be doing stuff other than internships. But for an internship, it paid pretty well.”

And for Diamond, it paid off with a full-time job.

Emily Curtis

Title: Analytics Intern

Education: Math major and Computer Science minor, University of Oklahoma; Master’s in Applied Mathematics, University of Washington

Area of focus: Injury prediction

Last June was a loaded month for Emily Curtis.

“I finished my Master's on June 9, got married on June 16 and started here on June 25,” Curtis said. “It was quite a month.”

Curtis sped her way through her undergraduate degree in her hometown of Norman, Okla., in under three years. She had always loved Math, so she began looking for careers where she could use it. After deciding she didn’t want to be an actuary, she came to the University of Washington to get a Master’s degree and become a data scientist.

Smith offered her the flexibility of a June start date so she could finish her Master’s program and she found herself fulfilling a childhood dream by becoming a rare female with a job in baseball operations.

“In the baseball ops group, I'm the only one. Some days with my husband and my male dog, I do not see another woman,” Curtis said. “I would say this group has been outstanding. I have had no issues with anyone in the analytics group. They just treat me like I'm anyone else and that's really what I'm looking for.”

Curtis is in a small Facebook group for women in baseball analytics, guessing that she’s one of about a dozen working in the industry.

Skylar Shibayama, Analytics Intern

Education: Statistics major, Yale University

Area of focus: Pitch evaluation

Shibayama’s senior project at Yale was building a tool that used public baseball data to model pitch quality. He also did some media and broadcasting work for the Yale baseball team after a failed attempt to walk on.

“My independent background was a pretty good fit [for baseball analytics] in terms of I had done a lot of projects on it,” Shibayama said. “It just wasn't as a job before.”

Upon graduation, the Shoreline, Wash., native chose to return home, in part to make sure he didn’t miss out on his little brother’s last year of high school. He took an assistant coaching job with his old high school basketball coach.

Shibayama said most people in his position go into banking, finance and consulting, but his focus was always more fixed on his own personal interests of sports, statistics and education. He also said his freshman year roommate, who now works for the Baltimore Ravens, helped motivate him to pursue a sports path.

Shibayama found out about the Mariners position when he got an email from David Hesslink, a former pitcher at MIT who has become a jack of all trades for the Mariners baseball operations department. The two had previously met through a mutual friend.

In his first year on the job, the 22-year-old ended up receiving a lot of the credit for imagining the deal that sent Denard Span and Alex Colome from the Rays to the Mariners last May.

After the end of last season, Shibayama was promoted to a new role as an assistant advance scout.