Mike Murphy isn’t just a longtime Giants employee. He’s a legend, as legendary as the Hall of Famers he has known and befriended.

Murphy has worked continuously for the Giants since they moved from New York before the 1958 season. He ascended from batboy to visiting clubhouse attendant to home clubhouse manager. You know the saying, “If you love what you do, you never work a day in your life”? Well, that’s Murph.

Murphy has decided to tell his story. Collaborating with MLB.com's Chris Haft, who covered the Giants full-time from 2005-18, Murphy, who’s now semi-retired but can still be found at Oracle Park more often than not, shares his wealth of experiences. He talks not only about the Giants, but also about dining with Frank Sinatra, meeting John Wayne and serving as Joe DiMaggio’s chauffeur.

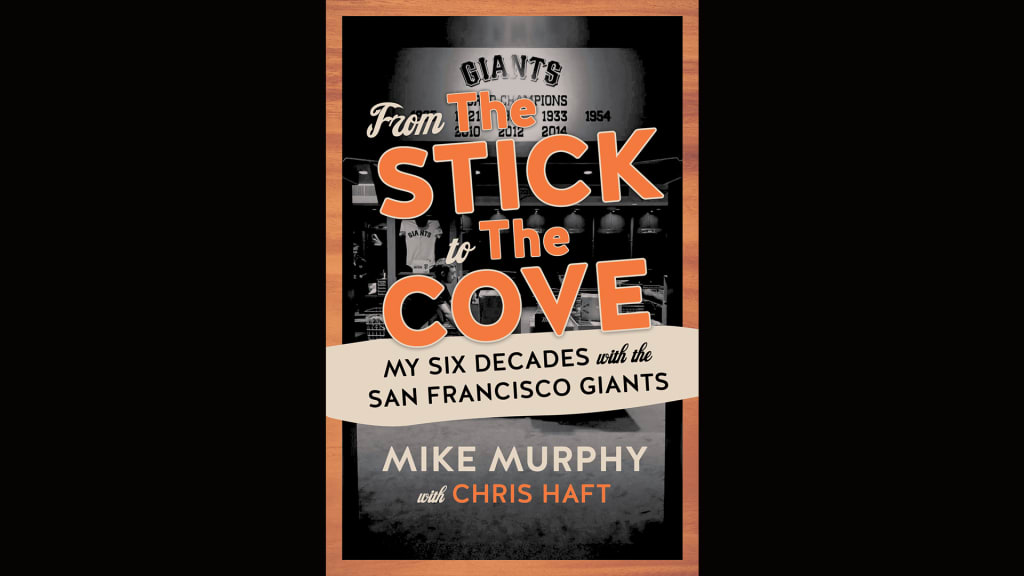

This excerpt about Murphy's friendship with Willie Mays in, "From the Stick to the Cove: My Six Decades with the San Francisco Giants" is presented with permission from Triumph Books. For more information or to order a copy, visit www.triumphbooks.com/fromthesticktothecove.

As for Mays, I still get as much of a kick out of him as I ever did. He drops by the clubhouse probably once or twice a homestand. We talk a lot, but it’s not just reminiscing about all those great times we had with the old Giants. We might talk about the current ballclub, the state of baseball -- once you get Willie started talking about baseball, it’s hard to get him to stop -- or we’ll discuss the kind of stuff that any pair of old friends might talk about, like family or mutual interests. As Mays likes to say, “Just talk.”

He will turn 89 years old in 2020. Almost everybody who has lived that long has experienced some physical challenges, and he’s no exception. His superior vision during his professional heyday enabled him to distinguish a fastball from a curveball more quickly than anybody could. But for the last few years, cataracts have virtually blinded him. His baserunning ability once bedeviled opponents and captivated fans. Now he tries to stay off his feet a lot, so he rides in a golf cart when it’s practical. He has heard more cheering than almost any human being on this planet during his years on this Earth. He can still hear the cheering as long as he keeps his hearing aids properly tuned and battery-powered.

Naturally, it’s tough to watch somebody you adore grow older. But Mays makes things better just by being himself. He can be a little grouchy at times. But he has earned the right. To this day, I get a thrill from watching him come through those clubhouse doors. Our friendship was never based on hero worship. It’s always been based on trust.

It’s funny, but before the Giants came West, I didn’t know much about him. Certainly, I had heard of him and knew that he was a fantastic center fielder. But partly because the Seals were a Boston Red Sox affiliate, Ted Williams was my first favorite ballplayer. Once the ’58 season started, it quickly became obvious Mays wasn’t just the Giants’ best player. He was the planet’s best player. I didn’t have time to help him with any special favors given how busy I was. And you know what? Mays noticed that and appreciated it.

Pretty soon, he and I became confidants. Lord knows, Mays needed friends. Despite having one of his best seasons -- the .347 batting average he recorded that season was a personal best -- he struggled to win over the San Francisco fans. Even the local newspapers took sides. The San Francisco News tended to be harsh on Mays mainly because another paper, The Call-Bulletin, signed him up to do a ghostwritten column. Purists dismissed Mays by insisting that Joe DiMaggio, a San Francisco native, was a better ballplayer. Newcomers to baseball -- and there were many of them due to the novelty of the Giants -- preferred Orlando Cepeda, the homegrown first baseman. Cepeda had a great year (.312 batting average, 25 home runs, 96 RBIs) and won the National League Rookie of the Year Award. But he was no Mays, who lost the National League batting title by .003 to Philadelphia Phillies star Richie Ashburn.

Mays and I rarely discussed such topics when we had our dugout chats. One subject Mays focused on, however, was my financial well-being. Mays was aware that we batboys and clubbies made very little money, and he intended to guarantee that I avoided any financial hardship. “I wanted to make sure that he understood that if he didn’t have enough money to buy a suit or a pair of pants,” Mays said, “I’ll take care of it. But I didn’t tell everybody about it.”

During the glimpses of game action that I was able to catch, I saw Mays do things nobody else could, especially on defense. Vin Scully, the great Dodgers broadcaster, summed it up best when he said that Mays played center field as if he were a shortstop, charging batted balls and coming up throwing. “You had to because we had some great runners in my time,” Mays said.

The other thing Mays did was play shallow in center, daring opponents to smack drives over his head. This often did them more harm than good. I asked him if he did this only at Seals Stadium, which had a relatively small outfield. “I played shallow everywhere because I figured if he hits it in the air, I could catch it. That’s the way I played. If the guy that’s hitting sees me playing shallow, he’s going to try to hit it over my head. And that’s how I got them out a lot because they hit it high and I could catch it without any problem.”

Just like the love of the game clause in Michael Jordan’s first professional contract that allowed him to participate in offseason pickup games, Mays needed something like that in his contract. There were times he wouldn’t leave Seals Stadium for three or four hours after the game ended because he’d play makeshift games with us batboys. He’d bat left-handed because if he had hit righty he couldn’t help but hit it out of the park. I played first base. “Doc” Hughes was the catcher. It was far from a real game since we never played nine-on-nine. But it was a heck of a lot of fun to play something resembling baseball with the best player in the world.

My fellow San Franciscans were still mostly unmoved. After Russian premier Nikita Khrushchev basked in a friendly reception during a 1959 visit to San Francisco, journalist Frank Coniff observed, “San Francisco is the damnedest city I ever saw in my life. They cheer Khrushchev and boo Willie Mays.”

If any of that stuff bothered Mays, he never showed it. He kept swinging as if his bat were an axe that would chop down the skepticism that loomed over him. His gargantuan home run on the final day of the 1962 regular season that helped send the Giants into a best-of-three playoff with the Los Angeles Dodgers for the National League pennant won him some believers.