We’ve all spent years cautioning against reading too much into early season stats, because they rarely ever end up looking the same at the end of the year. For example: Francisco Lindor probably isn’t going to hit .171 all season. Mike Trout probably isn’t going to keep hitting .413. (Probably, anyway. There’s nothing Trout can’t do.) Now, take that concept and cut them in half. You probably don’t want to put much of anything into splits at this point.

But that doesn’t mean we can’t at least have a little fun with some of baseball’s wildest splits over the first month-plus, can’t we? Even if these aren't likely predictive of the rest of the season, some of them may have a sliver of truth, and they're wild to look at right now nonetheless.

(All stats current entering Monday night’s games.)

Nick Castellanos, OF, Reds

Castellanos is off to red-hot start for Cincinnati, with his nine home runs tying for the Major League lead. He’s got the most hits in the National League. He is, quite simply, mashing.

He is also doing almost all of that mashing, to an absurd extent, in the friendly confines of Great American Ball Park. This is the one that got us started here.

Home: .393/.424/.893 -- 1.317 OPS -- 8 HR

Road: .260/.302/.400 -- .702 OPS -- 1 HR

Would you look at that? If he were to keep it up -- which, we cannot stress enough, he will not -- he'd have one of the best home hitting seasons ever compared with a road line that was something akin to Hanser Alberto's in 2020. Or, put another way: He has eight homers in Cincinnati, and 13 total hits on the road. That’s not entirely due to the fact that Great American Ball Park is baseball’s number one home run field, but it seems likely it’s not totally unrelated, either.

This is all the more entertaining given the fact that Castellanos spent years grumbling about the excessively deep dimensions of his long-time home in Detroit, where Comerica Park spans 420 feet to center. (“This park’s a joke,” he once said.) Of course, that all ignores the fact that he actually hit better in Detroit (.469 SLG/.807 OPS) as a Tiger than he did on the road in Detroit grays (.450 SLG/.760 OPS).

In fact, since that was also the case in his brief stint as a Cub in 2019 (1.162 OPS at home, .822 OPS on the road), one might argue that Castellanos just likes playing at home, no matter where that home is, better than anywhere else. That his current home fuels homers more than anywhere else -- there have been 745 more homers hit in Reds games at home as compared to Reds games on the road since GABP opened -- merely makes it look even more stark, even if this current split isn't likely to maintain.

Franmil Reyes, OF/DH, Indians

So what, exactly, is going on in Ohio?

Home: .400/.423/.900 -- 1.323 OPS -- 6 HR

Road: .111/.154/.222 -- .376 OPS -- 1 HR

Even that one home run on the road wasn’t crushed, really. Despite coming in Castellanos’ old Detroit home, Reyes pulled it down the line a mere 357 feet on a day where four balls went out to left field. Overall, this isn't really about contact; his strikeout rate is about the same both home and road. It's mostly about "hitting the ball hard in the air" in Cleveland as opposed to "softly and on the ground" on the road.

But wait! It gets more confusing. Here’s what Reyes did in 2020:

Home: .606 OPS

Road: .971 OPS

Taken together, these are almost assuredly two things without much greater meeting ... except for one fact we can’t help but pass along.

Coming into the season you knew two things about the Cleveland roster: One, that its pitching was likely to be very good. And two, that its lineup, aside at least from Reyes and José Ramírez, was probably going to be very weak. So far, so good on the projection front, because that's basically what's happened. The Cleveland arms are just outside the top 10 in ERA, and the bats have been tied for the second-weakest.

Why, then, has a cold-weather stadium in the first month of the season populated by a home team that has some top arms and few quality hitters been witness to the most home runs outside of Cincinnati? Progressive has generally been a somewhat neutral home run park. Is that changing?

(Our thanks to @DaveyBerris for this one.)

Evan Longoria, 3B, Giants

Did you notice who’s fueling the offense of the first-place Giants? It’s a pair of mid-30s veterans who you probably thought were well past their primes in Longoria and Buster Posey. Longoria, who turns 36 in October, posted a mere 96 OPS+ in his first three years in San Francisco. This year, he’s got a 155 OPS+, fueled in large part by a suddenly great hard-hit rate that ranks near the top of the sport. Sure, his strikeouts are at a career-high 24%, but with production like this, who cares?

You might think, given both the premise of this article and the pitcher-friendly nature of Oracle Park, that this is going to be an inverse-Castellanos situation, but that’s not it; Longoria has actually hit a little better at home this year. No, this one’s about pitchers, and which hand they’re throwing with.

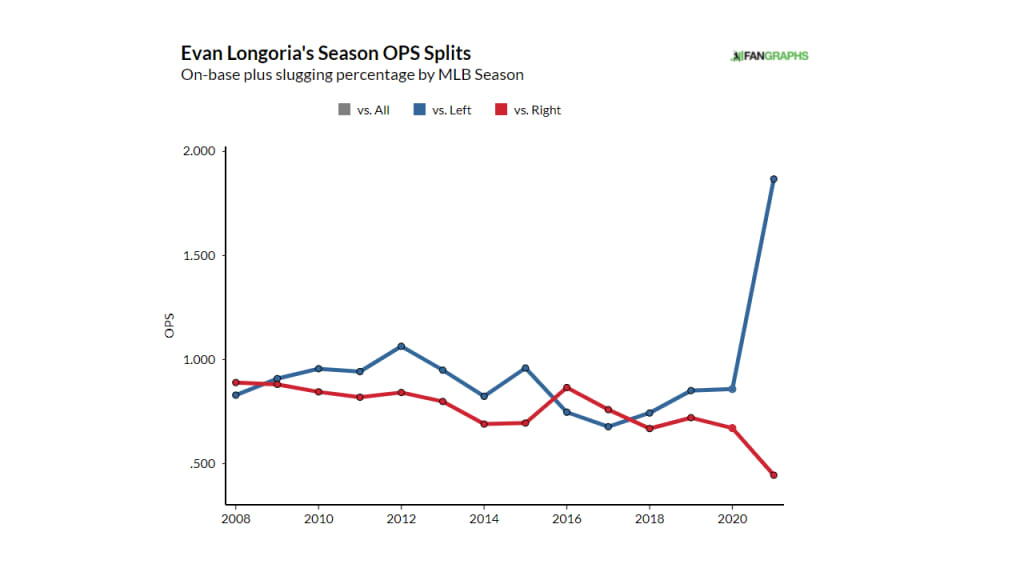

Vs. LHP: .524/.677/1.190 -- 1.868 OPS -- 4 HR

Vs. RHP: .167/.216/.229 -- .445 OPS -- 0 HR

Longoria has absolutely slammed lefties this year, better than any hitter in baseball, and by a considerable amount. So here's the real question, then: Should we be excited about what he's doing against lefties? Or worry that he's not doing any of it against righties, who he'll see more of? Maybe it's easier to see on an annual platoon split graph.

Let's go out on a limb and say he will not continue to do this against lefties all year, though of course he's long been better against southpaws over the years.

Setting aside again how early it is, it's interesting to note how much the Giants seem to be attempting to put him in position to succeed. Longoria, so far, has taken 38% of his plate appearances against lefty pitchers, which would be the highest of is career, and well above his 28% career mark, as well as the 27% he had in 2020. But maybe that 38% is also underselling it, too. Longoria was unavailable for the home opener on April 9 due to having received the COVID-19 vaccine that day; he surely would have started against lefty Austin Gomber otherwise. Then, a mild hamstring strain later in the month cost him two starts, one of which was started by a lefty.

"Putting your players in the best position to succeed" is half the point of a manager, isn't it?

That all makes sense, and it's good strategy. Or, at least, it will be once Tommy La Stella gets untracked. Since Wilmer Flores, also a righty hitter who hits lefties well, is an awkward platoon partner, Gabe Kapler would surely like to see noted righty masher La Stella offer a little more than the 83 OPS+ he's contributed so far.

Jorge Soler, OF/DH, Royals

This early split, we think, might actually have something more real to it, because it's the continuation of one we've seen for some time. Soler's best position has long been "designated hitter," and in 2019-20 that's where he spent about two-thirds of his time. That's where he started 14 of the first 17 games of this season, too. But then, Opening Day right fielder Kyle Isbel was optioned to the alternate site, and sometimes right fielder Hunter Dozier starting getting more of his playing time at third base -- which was the original plan anyway -- and now, Soler has started nine straight games in right as Ryan O'Hearn gets the bulk of the DH time.

Soler has never been a highly regarded defender, but when he's wearing the glove this year, it has particularly not gone well.

As RF: .125/.182/.225 -- .407 OPS -- 0 HR

As DH: .244/.364/.444 -- .808 OPS -- 2 HR

That is, currently, the largest split between hitting from the same player at a different position in baseball. Now, again, we're talking about 102 plate appearances, total, which would be enough to hand-wave away except for the fact that Soler had an OPS 203 points higher as a DH in 2020, and 202 points higher in 2019 as a DH than he did in right, and 231 points higher in 2018, and really it's just been like this for his entire American League career -- .914 OPS as a DH, .719 as an outfielder -- and since the glove is poor anyway, maybe the Royals might just consider letting him be a bat-only player full-time?

That might yet be what happens soon enough, anyway. When the injured Adalberto Mondesi returns to play shortstop, it might free up Nicky Lopez to move back to second and push Whit Merrifield back to right, though that would leave the defensively-limited O'Hearn without a home.

The funny thing is, there's long been a "DH penalty" in baseball, in that most batters perform worse as designated hitters than they do as fielders. For every rule, there's an exception. Soler seems to be that player.

Adam Eaton, OF, White Sox

Not every split is about home/road or lefty/righty. You can, for example, split performances in a team's wins and losses. As you'd expect, there's a very strong correlation there, because when a player performs well, his team is then more likely to win. Paul Goldschmidt, for example, has a .939 OPS when the Cardinals win and a .283 OPS when they lose. Absolutely nothing about that ought to be surprising. Nothing, except, for what Eaton is doing.

In Wins: .184/.231/.306 -- .537 OPS -- 1 HR

In Losses: .256/.373/.465 -- .838 OPS -- 2 HR

That's not the largest gap in baseball so far -- Rangers outfielder David Dahl has a slightly larger one, but since he's not performing much overall we're highlighting Eaton here -- and almost certainly this doesn't actually mean much of anything, especially because it's not true over Eaton's career. And yet: This happened in 2020, too! Last year, Eaton had a .542 OPS when his Nationals won, and a .732 OPS when they did not. File this one more under "weird yet fun" than anything else, but the 2021 White Sox have had a lot of weird things happen, and this is one of them.

Marcell Ozuna, OF, Braves

Last year, Ozuna was one of the best hitters in baseball overall, and especially so against lefties, when he mashed a .356/.463/.867 line against them. As a follow-up, this is what he's done so far in 2021.

Vs. LHP: .042/.042/.083 -- .125 OPS -- 0 HR

Vs. RHP: .250/.351/.369 -- .720 OPS -- 3 HR

That line against lefties comes out to "one hit, a double, and no walks in 24 plate appearances," which is almost inconceivable, really. This has really been part of a lineup-wide issue for the Braves, who have had baseball's second-worst line against lefties so far this year. Atlanta somehow has just 29 hits against lefties; meanwhile, Baltimore outfielder Cedric Mullins III has 16 by himself. The Braves are simply too talented to keep that up for long.