Manuel Oliver sits on a Zoom call from his home in Parkland, Fla., as images and art of his son adorn the wall behind him. He is reflecting on all the ways his life has changed since his son, Joaquin, was one of 18 students murdered in a mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High on Feb. 14, 2018.

"Easy things, like going to the grocery store. You don't buy the same things -- you don't buy any more cookies, you don't buy any more hot dogs. And traditions can hurt a lot. I love that I was able to do everything I could with Joaquin -- related to music, related to baseball, related to dancing. But there's no way I can keep doing those things and enjoy them. I did love the idea that we were doing this campaign because it's a different story. The fight against injustice. But I can't enjoy watching a baseball game without Joaquin sitting next to me eating popcorn, saying 'shut up, dad, you don't know what's going on.'"

-----------------------------------

Joaquin came to America as a three-year-old from Venezuela with his mom, Patricia, and father, Manuel, in 2004. Manuel never thought something like what happened in February 2018 could ever happen -- "that somebody could get into a school and randomly shoot kids."

But Manny doesn't regret moving to the U.S. and, like many of the other survivors and families involved in the Parkland shooting, he's decided to take a stand for his son. According to Everytown for Gun Safety, an estimated 3 million kids are exposed to shootings per year. There have been 83 school shootings in the two years since Parkland. Close to 40,000 people were victims of gun violence in 2019 alone.

In response to these shocking numbers, Manny created Change the Ref -- an organization that "uses urban art and nonviolent creative confrontation to expose the disastrous effects of the mass shooting pandemic."

And this year, that creative confrontation has come in the form of Joaquin's favorite pastime: Baseball.

Manny has worked with teams around MLB to put Joaquin's cardboard cutout in 15 different stadiums. A subtle, yet powerful protest. A stinging reminder of what happened and what, somehow, continues to happen.

Here he is at a Dodgers game.

At Tropicana Field, home of the Rays.

And Angel Stadium in Anaheim.

Joaquin loved the game of baseball -- playing 10 years of local ball in Florida. A neighborhood field has since been named in his honor. He strongly believed in hometown team pride and loyalty -- cheering avidly for the Marlins all his life. He also always rooted for Venezuelan-born stars like Miguel Cabrera (but if the Tigers came to town to play the Marlins, it was always local team first, his dad reminds me).

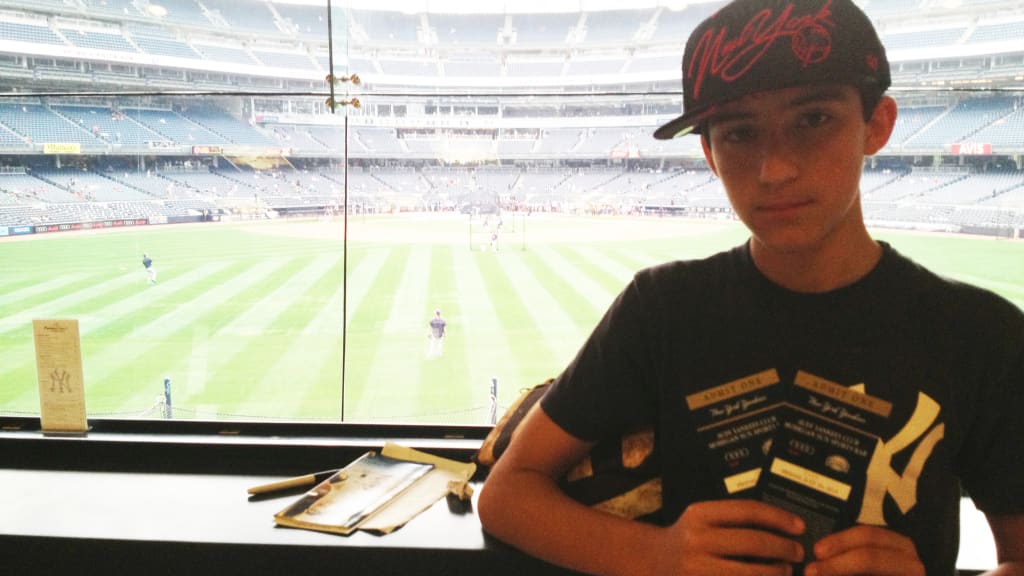

He and his dad, who was admittedly not a baseball fan until Joaquin took an interest, did ballpark tours to different parts of the country. (Manny tells me a story about not recognizing Venezuelan great Johan Santana at a local grocery store and Joaquin being incredulous with him about it once he got home).

"We did [ballpark tours] twice, two years in a row, Joaquin and myself," Manny says. "We visited different ballparks. That's how we saw Fenway Park, went to the new Yankee Stadium, we went and saw the Mets. He had his favorite player everywhere, we would buy the jersey. It was a whole magical thing. ... I was learning from Joaquin that there was this wonderful thing out there called baseball. And I was enjoying him because of it."

The two ate mostly fast food, or "crap," as Manny puts it, and would create rating systems for each stadium -- ranking hot dogs, atmosphere and other aspects of their experience. (Fenway Franks were Joaquin's favorite.)

"The plan was to really keep doing it," Manny tells me. "Me, turn into an old guy, and my grownup son along with his kids, take me to the ballpark."

Baseball even helped Manny and his wife, Patricia, make friends after immigrating from Venezuela.

"[Little League] is where we made friends, Patricia and myself, because of Joaquin," Manny says. "We started meeting people and we started enjoying the park -- the whole experience of the kids growing and getting better and better."

And now, two years after he lost his life, baseball and Joaquin have teamed up once again. He's gone on one of his own little ballpark tours. This time, to remind all of us that we need to do something about a problem that's been plaguing America for years.

"We all know that gun violence in America is totally out of control," Manny says. "We have a gun industry that is making a lot of money and we have people dying every single day. How do we fight that fact? We need to put a new narrative on the gun culture that we practice here in this country. We need to reach other demographics. Major League Baseball decided to give this option of bringing fans thrown onto cardboard cutouts. And I happen to have no other way to bring my kid to the ballpark. OK. Bingo. We have a way to send a message."

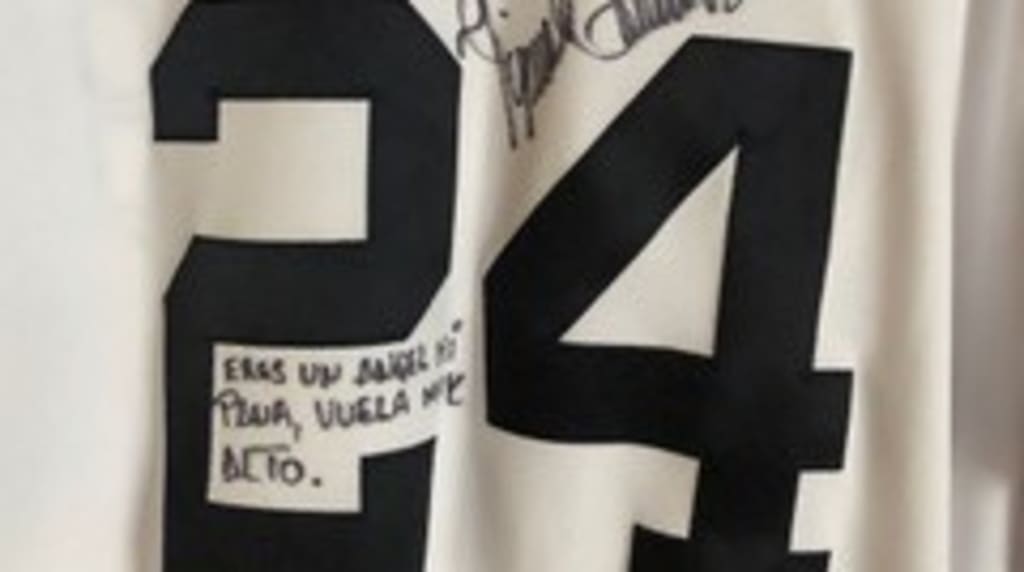

Teams have seen what Manny's been doing and have reached out about putting Joaquin in their stands. The Dodgers have him there for every game. The Blue Jays reached out and recently sat him in Buffalo for a game against the Yankees. Cabrera sent Manny a signed Tigers jersey with a personal message to "Guac," Joaquin's nickname:

To Joaquin “GUAC,” with much affection. You are an Angel buddy, fly high - Miguel Cabrera

But one of the lasting images was when Venezuelan-born pitcher Jesús Luzardo, himself a 2016 graduate of Marjory Stoneman Douglas, posed with a Joaquin cutout at the Oakland Coliseum.

"You find out how vulnerable life is," Manny says. "These two kids met at Parkland. On the basketball court. It's so fragile. ... Any of these kids could be a victim in one second. Now, we have one of them drawn on a cardboard and the other a baseball star."

October is now nearly here and Joaquin's Marlins, overcoming great adversity and low expectations, are in position to make the playoffs for the first time since 2003. Although it pains Manny too much to watch the games without his son, he hopes Joaquin's message and spirit and cardboard cutout endures throughout the postseason and World Series.

"Joaquin is making all this happen," Manny says. "Let's just spread the message. We're trying to save some lives here."