A version of this story originally ran in July 2020.

One benefit to so much of life being on pause during the pandemic is the time it has allotted for the discovery of previously elusive information. Important things, obscure things, mind-bending things.

Things like Phil Jackson hitting a double off Satchel Paige.

Whoa, that’s quite a sentence. It puts Paige, one of the biggest stars of the Negro Baseball Leagues, and Jackson, an 11-time NBA champion head coach, on the same baseball field at the same time. In northwest North Dakota, no less.

“We were two ships passing in the night,” Jackson tells MLB.com, “and you would never expect it to happen.”

It happened, the then-74-year-old Jackson says, in the summer of either 1963 or ’64, when he was playing American Legion ball in his hometown of Williston, N.D., and Paige was barnstorming the country with some Negro Leagues pals.

Many great stories involving the legendary Paige are apocryphal. And perhaps this one is too good to be true, too. But this tale has been out there for a while: It popped up briefly in a few books (including “The Jordan Rules”) and newspaper articles during Jackson’s coaching career, but in the pre-Internet age it largely went unnoticed, which is why we decided to get to the bottom of it. And really: Why would the Zen Master invite bad karma upon himself by making this up?

As Jackson’s longtime friend and high school teammate Bob Sathe insists, “If he said it happened, it happened. He’s not one to embellish.”

So let’s use the story of Jackson’s performance against Paige as occasion not just to celebrate an obscure intersection of sports legends but to bring to light the baseball life you probably didn’t know Jackson once lived.

Nobody’s suggesting Jackson’s baseball past is as fascinating as that of Michael Jordan, who briefly left Jackson’s Chicago Bulls to chase a diamond dream.

But Jackson was once serious about baseball.

“If you had told me when we were kids that he would be a star in a major sports operation,” says Sathe, “I would have guessed baseball.”

Baseball was a big deal in tiny Williston, which had a population south of 10,000 when Jackson moved there in sixth grade. From 1954-57, the town had an entry in the independent Manitoba-Dakota (or “Mandak”) League -- a league that gave former Negro Leaguers (including Paige, who pitched for the Minot Mallards in 1950) an outlet to continue their careers, alongside former Major Leaguers, Minor Leaguers and local talent.

Between the presence of the Williston Oilers in that league, the annual winter baseball banquets and World Series film tours that would come to town, and his own experiences on the field as a lanky left-hander and first baseman, Jackson was a bona fide baseball fan. He was particularly enchanted by Roger Maris’ chase of the single-season home run record in 1961.

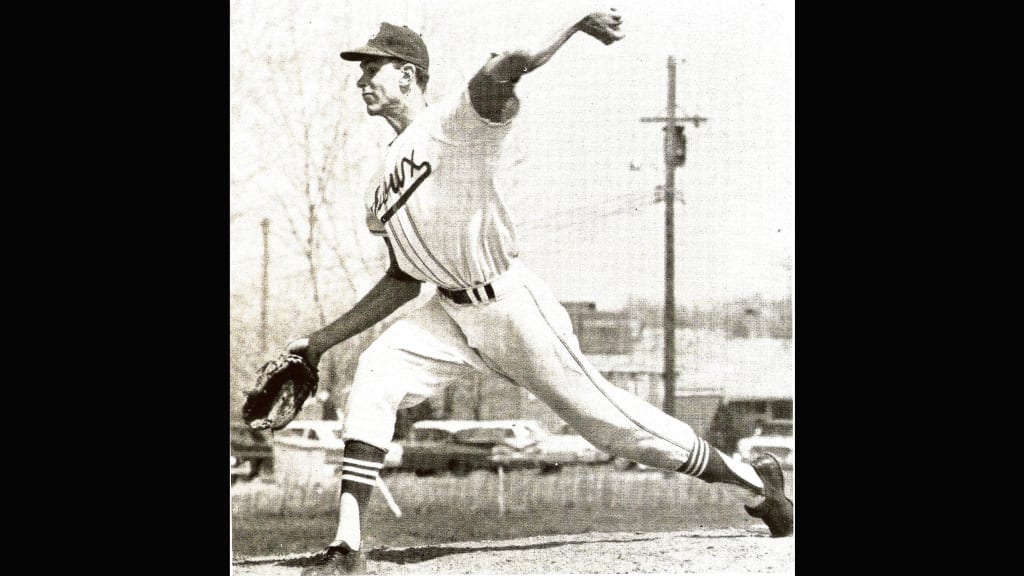

Jackson didn’t have Maris-like power. But because he stood about 6-foot-6 by the end of high school and grew another two inches in college, he had quite a long stride in his pitching motion.

“Every time I threw the ball,” he says, “my hat would fall off.”

With his long arms, Jackson had a sidearm curveball that, in Sathe’s memory, forced left-handed hitters to bail from the box.

Alas, Jackson didn’t always know where it was going.

Bill Fitch, the UND basketball coach who recruited Jackson years before going on to an NBA Hall of Fame coaching career of his own, first heard of Jackson through the baseball scouting grapevine. He once told Jackson biographer Roland Lazenby, “[Jackson] couldn’t find home plate with a Geiger counter.”

“I was wild,” Jackson admits. “I got better as I got older. I struck out a lot of batters, and I walked a lot of batters, let’s just say that. But I had a good time.”

Jackson’s height and basketball profile increased at UND, but he kept pitching, even though the brutal North Dakota winters didn’t aid his development. In his sophomore year at UND, he led the team in wins (five), ERA (2.30) and strikeouts (51). In his junior year, he threw six complete games, including two shutouts, while again leading the team in strikeouts (76).

During that junior year, Jackson’s baseball coach, Harold “Pinky” Kraft, told him the Dodgers had shown interest in him. But Kraft informed the Dodgers scout that Jackson’s future would be in basketball.

It took a little more time for Jackson to come to the same conclusion. He had his awakening that summer, when he was a pitcher for the Mobridge Lakers, a semipro team in the now-defunct South Dakota Basin League.

“We were playing a Class C team from Aberdeen [S.D.], and these kids were tattooing the right-field wall with my fastball,” Jackson recalls. “After a couple weeks of staying in boarding houses and working jobs on the side, I had lost 15 pounds. I thought, ‘Hmm, this is not going to work out very well. I’m not going to have much of a basketball body left.’”

By his senior year at UND, in 1967, Jackson was down to just one sport. In lieu of participating in baseball, he spent the spring meeting with various NBA and American Basketball Association coaches and general managers. He wound up getting selected by the New York Knicks in the second round of the NBA draft.

Interestingly, decades before Jordan’s flirtation with baseball, Jackson had wondered aloud to Danny Whelan, the longtime Knicks trainer who had previously worked with the Pittsburgh Pirates, if he could possibly go back to baseball.

The curiosity never amounted to anything (Jackson wound up playing 12 seasons in the NBA and was a key member of the Knicks’ last title in 1973). But it gave him a frame of reference in his coaching career, when a certain superstar shooting guard joined the Birmingham Barons in 1994. Jackson was empathetic toward Jordan’s unorthodox and controversial mission.

But the most direct way that baseball wound up impacting Jackson was through his experience as a coach in Williston’s Babe Ruth League (a league for teenage players) while he was still in high school and college.

When Jackson was 20, he guided his team to the state championship finals.

“The kids were only five or six years younger than I was,” Jackson said. “Without a doubt, it taught me the discipline it takes to coach.”

During his Bulls days, Jackson would joke with Bulls and White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf that if Reinsdorf was ever in need of a backup manager for the Sox, his services were available. It’s safe to say, though, that Jackson went the right route with his coaching career.

Still, baseball left him with some stories to tell -- none better than the one about facing Paige while playing American Legion ball in the summer either after his senior year of high school or his freshman year of college (Jackson wasn’t exactly sure which).

Paige, who was 6-foot-4 and quite lanky himself, spent 40 years in professional baseball, pitching in more than 2,500 games and winning around 2,000 of them, if we are to believe the records he personally kept. When he wasn’t suiting up for organized teams in the Negro Leagues, the Major Leagues or the Minor Leagues, he was barnstorming -- playing against sandlotters and semipros from coast to coast.

That’s how Paige and Jackson crossed paths in an exhibition.

“It was a collegial kind of thing, in the middle of western North Dakota, baking hot in the summertime in a dusty small town,” Jackson says. “They drew a big crowd for that. I remember [Paige and his teammates] seemed to be having a great time. I was pitching [opposite] Paige, and I was so gangly and had to pull my hat over my left eye because the sun was coming through the grandstands. They were razzing me from the dugout.”

When Jackson faced Paige at the plate (no designated hitters here), he didn’t encounter the frightening fastball that had served Paige so well on the big stage. Though Paige would go on to make one last big league appearance for the Kansas City A’s in 1965, he was, at this point, far removed from his last legitimate MLB season in 1953, and was approaching 60 years old.

“He was probably throwing 70 miles per hour,” Jackson says. “I think he gave me a pitch to hit [on purpose], and I hit it off the center-field wall. It was a fun game.”

And it’s a fun story. Phil Jackson vs. Satchel Paige. A literal tall tale.