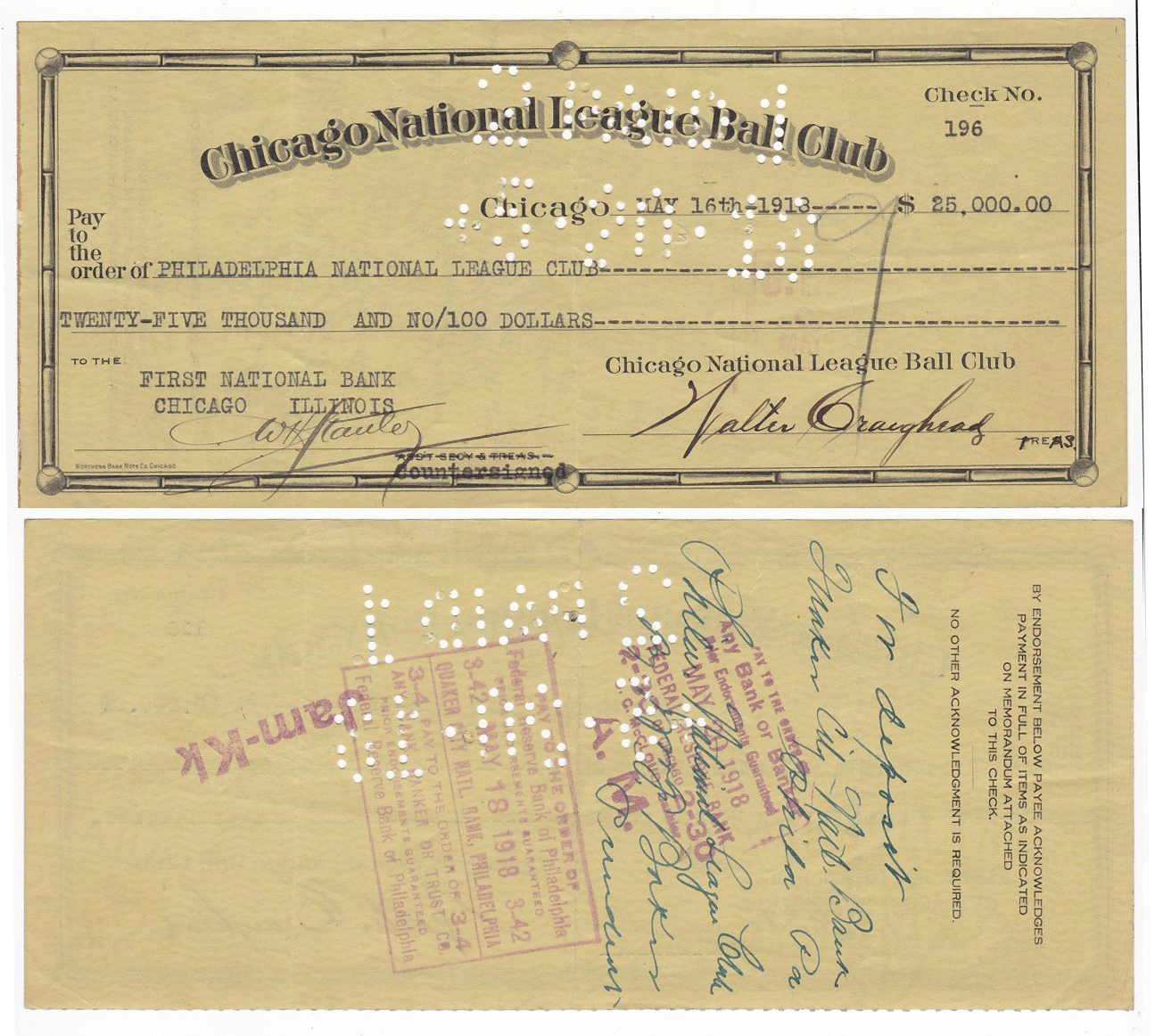

Dec. 11, 1917, is a date that lives in Phillies’ infamy. It was that day club president William F. Baker traded pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander and catcher Bill Killefer to the Chicago Cubs for two mediocre players: pitcher Mike Pendergast and catcher “Pickles” Dillhoefer. And the real prize for Baker: $55,000.

The trade spawned a profound and transformational change in the Phillies’ fortunes, condemning the club to decades of terrible baseball and cementing its reputation as the “losingest” Major League Baseball franchise ever. It can be truly said that after the Alexander trade, providence abandoned the Phillies to the purgatory of interminably doomed seasons.

How fundamental and enduring was the shift in the club’s destiny?

Consider this. During the first 35 years of the Phillies’ existence (1883-1917), their overall win-loss totals were 2,502-2,364, a winning percentage of .514. Not great, but also not awful, especially given the club’s early struggles in its formative years. Indeed, things were looking up for the team at the close of the 1917 season. The Phillies’ cumulative record was 138 games above .500, the most it had ever been at a season’s end.

After Alexander’s trade, the Phillies’ won-loss record took a nosedive over the next 31 seasons. Starting in 1918 -- the first season without Alexander -- the club finished 14 straight seasons and 30 of the next 31 (1918-1948) without a winning record. In 16 of those seasons, the Phillies ended up in last place, and in next-to-last place eight other times. In doing so, the team lost 100 or more games 11 times. The club managed to finish in the first division (fourth place) only once -- 1932 -- which was also the only season it had a winning record (barely) at 78-76. The result in terms of total victories and defeats was predictably horrendous. Between 1918-48, the Phillies went 1,752-2,941, a paltry winning percentage of .373.

Why deal Alexander in 1917? He had won 30 or more games for the Phillies each of the three preceding seasons and was regarded as one of the premier pitchers of the era. Moreover, he was 30 years old and still in the prime of his career. What possible justification could there be to trade him?

For Baker, there were three.

First, the money. $55,000 helped him cover the club’s payroll and other operational expenses without dipping into his own fortune.

Second, he rid himself of Alexander’s and Killefer’s lofty salaries. The pitcher was paid $12,500 in 1917 -- more than double what Alexander had earned in 1916 -- and significantly more than the salary of any other member on the team. Killefer, $6,500.

Third, the players the Phillies obtained earned comparatively far less. Playing for the Cubs in 1917, Pendergast was paid $3,000, and Dillhoefer $2,000 -- a true measure of their marginal value as players. With the trade, Baker dumped $19,000 in salary while taking on only $5,000. (The disparity would have been even greater had Alexander not been dealt since he made it clear he expected a substantial salary increase for the 1918 season.)

Baker focused on the financial advantages in making the trade and later admitted, “I needed the money.” But that explanation was blatantly misleading. He was a wealthy businessman, as was evidenced by the fact he owned the majority share of the Phillies’ stock. A more accurate statement would have been, “I needed the money so I wouldn’t have to open my own wallet to fund the Phillies.” Baker firmly believed the club should pay for itself. That meant running the Phillies on a shoestring budget that avoided deficits and never required the use of his money nor that of other stockholders to cover revenue shortfalls. Baker and other members of the board of directors were only interested in reaping dividends from their original investments in the franchise and abhorred the thought of contributing their own cash to keep the team afloat financially.

The true cravenness of Baker’s motivation to send Alexander packing is most clearly shown in another reason he made the deal. Baker became aware of the high likelihood Alexander would be designated 1-A by his draft board in St. Paul, Neb., and be among the first group of men from that area called up for military service during World War I. If this happened, Alexander would be lost to the Phillies for at least the 1918 season, and perhaps longer depending on the duration of the war.

Baker’s concerns transcended the threat of Alexander being drafted into the U.S. Army. There was the chance he could be wounded or killed fighting on the Western Front in France. Then, Alexander’s value as a commodity to sell to another club for big money would be greatly diminished or even disappear altogether. Baker decided to deal him rather than risk that happening. Unlike the Phillies’ president, Cubs owner Charles Weeghman was willing to gamble on Alexander’s future and seized the opportunity to acquire the great hurler.

Philadelphia was outraged by the deal. Baker didn’t help his case in justifying the trade when he offered the stupefying explanation that just because Alexander had won 30 or more games for the last three years, “There is no reason for believing that he would be better next year.” One Philadelphia sportswriter cast the trade in sharp relief when he wrote that Phillies manager “Pat Moran lost his ballclub today.”

With Alexander and Killefer gone, the results were predictable. The Phillies toppled from second place in 1917 to sixth in 1918 with a 55-68 record. Moran singed Baker’s ears with his criticisms of the trade, and the club president reacted by firing him, claiming the manager had caused the poor season by not strengthening the team judiciously.

Having become president during the 1913 season upon the death of William H. Locke, Baker passed away after the 1930 season. But so pernicious and enduring was his catastrophic weakening of the Phillies with his “Stars for Cash” philosophy to bankroll the team that its consequences afflicted the club well beyond his death.

The ultimate reckoning of Baker’s tightwad stewardship of the Phillies took place on July 15, 2007, when the club lost its 10,000th game, becoming the first American professional sports franchise to reach that dubious figure. You can thank William F. Baker. Without him, realizing that shameful feat would not have been possible.

The trade of Grover Alexander was a watershed moment in club history. It marked a turning point after which things were never the same. Unfortunately, the turn pointed downward.

Phillies’ fans have a well-deserved reputation as eternal pessimists, caring only about the empty part of a half-filled glass, and tarnishing every spark of hope with forebodings of doom. If you are one of those fans, if you cannot escape the haunting and pervasive sense of defeatism in supporting the team, then blame William F. Baker. It all started with him and the deal that sent Grover Cleveland Alexander away.

Regard the check as evidence of the blood money Baker accepted to betray the Phillies and their fans.