“Adapt or die,” goes the old saying, and Clayton Kershaw transitioning from a fastball-first pitcher to a slider machine over the years has certainly helped keep him alive in the Major Leagues as his fastball velocity has waned.

Not everyone is Kershaw, of course, trying to maintain best-in-class ability, but every pitcher is trying to be the best version of themselves. Unless you’re Max Scherzer just trying to keep on doing the same thing that works great, that means changes. It means trying to perfect a new pitch, or use the pitches you have differently, or throwing harder, or with more movement.

It doesn’t always lead to success, or if it does, it might only work for a short time before the hunt for the next new thing is on. But early in 2022, we've seen some really interesting changes from pitchers across the spectrum, and we're not just talking about the "sweeper" that is all the rage in pitching circles right now. (Though we might have included Andrew Heaney here if he were not injured; same for Alex Cobb.) We've identified six of the ones that fascinate us the most here. These pitchers are doing something a whole lot different, and they're benefiting from it.

Shohei Ohtani, Angels

What’s changed: His slider is even better

Didn’t think he could get better, did you? While early-season Hitter Ohtani has been just OK, early-season Pitcher Ohtani has been nothing short of spectacular, striking out more than 40% of the hitters he's faced.

It’s not just that he’s throwing harder, though he is; his four-seamer, which was 95.6 mph last year, is now 97.5 mph. It’s not that his walk rate has improved, though it also has. It’s that his slider, already one of his best pitches, now moves differently. It’s thrown harder, up from 82.2 mph to 84.8 mph, but more impressively, he’s maintained the movement on it, at 16 inches of horizontal break.

If it’s not clear what that means, consider this. Movement requires time. More velocity means less time on the way to the plate. To take away time, yet have the same break, means it’s breaking more by comparison. And indeed it is; last year, it broke 115% more than other sliders around his velocity. This year, it’s 152%. That’s more break, compared to velocity, than any other regular pitcher’s slider in the game.

When it works right, it looks like this.

When you have a pitch like that, you throw it more, and he has, because it’s now essentially tied with his four-seamer for his most-used pitch. He’s allowed just three singles on it. We cannot emphasize enough how much you ought to ignore that 4.40 ERA, because absolutely every underlying metric says he has performed far better than that. This is the best Pitcher Ohtani has ever been.

Eric Lauer, Brewers

What’s changed: He throws a lot harder now

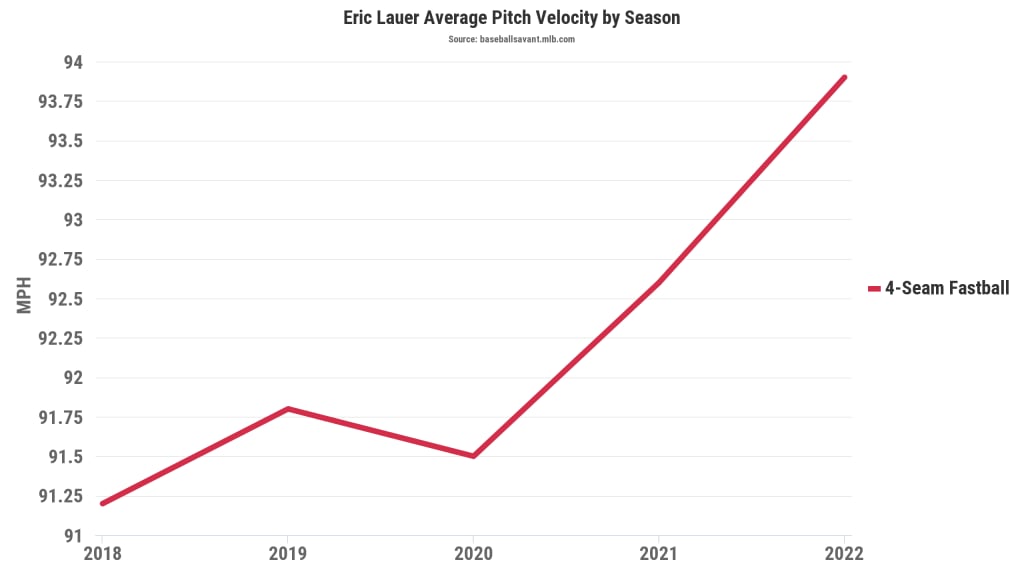

Just what the Brewers so badly needed: Another quality starting pitcher. The old Lauer was … fine. He was fine. There’s value in a decent back-end starter, as he was for San Diego in 2018-’19 (4.40 ERA), and then he was better than that in 2021 for Milwaukee, putting up a 3.19 ERA in 118 2/3 innings. But it came with a ceiling, it seemed, because he just didn’t throw that hard, averaging 91.6 mph on his fastball through the end of 2020.

That hopped up to 92.6 in 2021, which was just a prelude to what’s happening now, which you witnessed if you saw Lauer shut down the Phillies (13 strikeouts over 6 scoreless) on Sunday Night Baseball in Philadelphia, arguably one of the most impressive starts in team history. Lauer, to date, has made 77 career starts. Rank them, top to bottom, by fastball velocity. (One is missing, because it came in a non-MLB park in Mexico.) Three of the top four have come in his three starts this season. The new Lauer throws cheese. He is, improbably, one of the harder-throwing lefty starters now.

You could see the beginnings of this last season, as his mechanics changed and he got further away from a 2020 shoulder injury. Not only is the velo up, but he’s throwing it higher in the zone more often than ever, and yet he’s throwing the pitch less than ever, pairing it with a slider, cutter and curveball that all help his heater play up.

Suddenly, Lauer has a 34% strikeout rate, a huge jump from the 22% career mark he’d had before. His fastball has a .158 average against. He’s no longer a decent soft-tossing lefty. At 26, he might yet be the next outstanding Brewers starter.

Jorge López, Orioles

What’s changed: He throws a LOT harder now

You thought Lauer’s tale of increased heat was fun? He, at least, was moderately successful before, so strap in for this one.

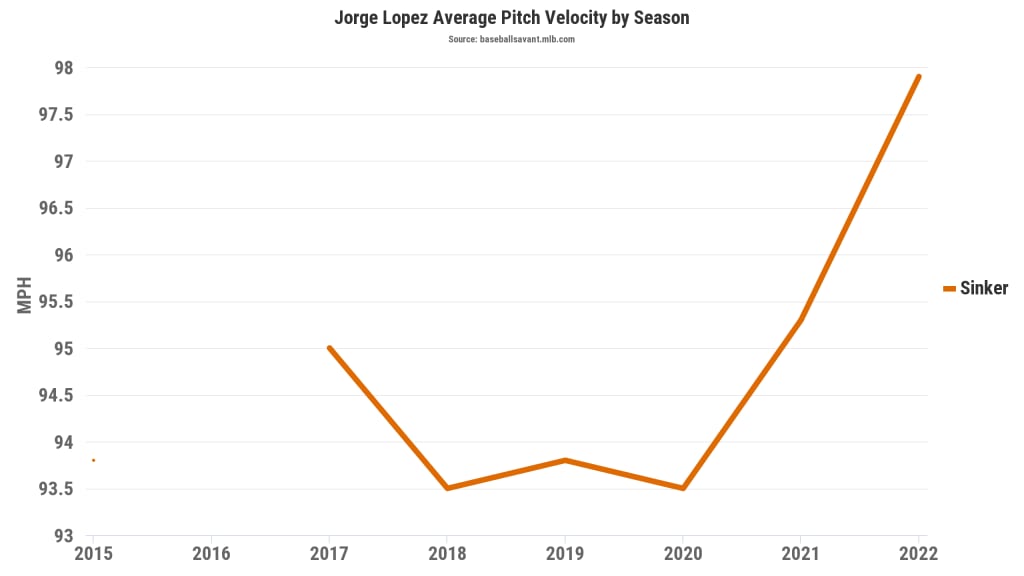

López, a second-round pick of the Brewers back in 2011, has been around for a while, and for the most part, he’s just been a guy. That’s considerably different from the fact that now, he might be A Guy, because he suddenly looks like an entirely different pitcher from the one who wore a 6.07 ERA for the Orioles last year.

Let’s back up for a second. López got into 102 games as a swingman for the Brewers, Royals and Orioles between 2015-’21, and if you remember him at all, it was probably because of that one time back in 2018 when he took a perfect game into the ninth inning. No one who pitched as many innings as he did had an ERA higher than his 6.07. No one really came close. The Royals, always desperate for pitching, cut him loose in August of 2020.

He landed in Baltimore days later, posted a 6.13 ERA for the O’s across 2020-’21, and a below-average pitcher on a below-average team is one that is easy to lose track of. It also means you might not have noticed that he was considerably better in the final weeks of the season after he was finally bounced from the rotation to the ‘pen.

And now? Now, finally a full-time reliever for the first time, he’s junked his four-seamer, which had a .617 career slugging against. Now, his sinker, which was around 94 mph back in 2018-’19, is nearly 98 mph. It’s the largest year-over-year velo jump in baseball.

It makes hitters as skilled as Giancarlo Stanton look like this:

Now, he’s jumped his strikeout rate from 20% to 35%. He’s yet to allow a home run, after giving up 25 last year; he's allowed only two hard-hit balls. Despite the fact he's been in the pros for more than a decade, López is still only 29 years old. There may yet be some there there.

Kyle Gibson, Phillies

What’s changed: Somehow, everything

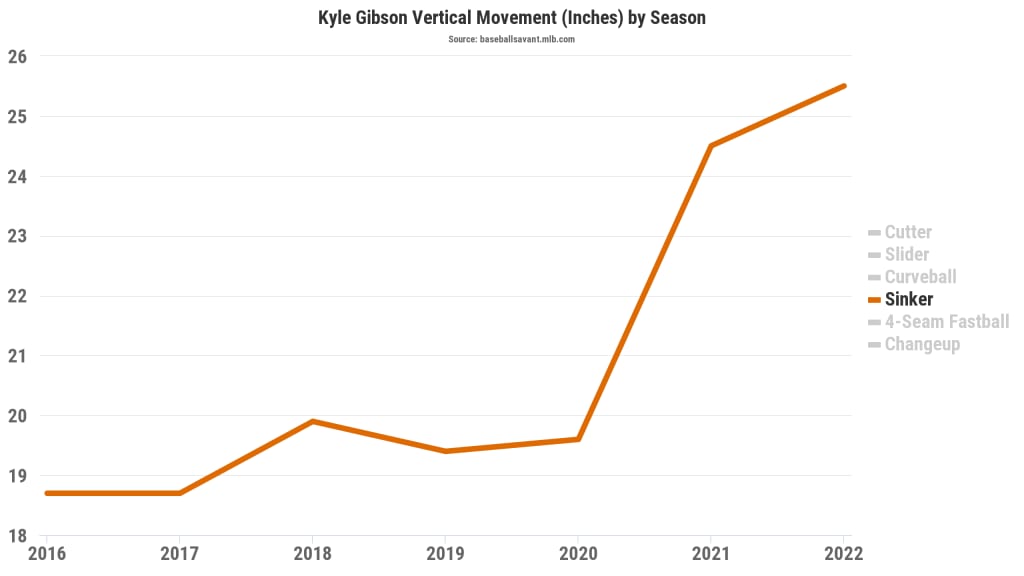

Gibson turns 35 this year, which means he’s been around long enough to feel like his story had been written. A first-round pick way back in 2009, he’d spent the first eight years of his career (2013-’20) with the Twins and Rangers as a competent back-end starter, one you could count on for 25-30 starts of 4.50 or so ERA pitching. Useful, for what it is.

Last year, with the Rangers, he pitched well enough to make the All-Star Game, but it felt fluky at the time, because little had changed in his underlying numbers. That's exactly what played out after his trade to the Phillies, when he posted a 5.09 ERA in 12 games.

This year’s 3.47 mark may not wow you, but something is different. After years of a strikeout rate hovering in the average-to-below range, he’s up to 26%, easily a career high. He’s never had a swinging strike rate anywhere near this. But unlike most of these other names, he’s not throwing harder. He’s actually throwing softer, as his 91.5 mph sinker velo continues a soft downward decline from his peak of 93.2 mph back in 2019.

What’s different, then, is two things. First, he added a cutter last year, which, at 89 mph, gives him something in between the low-90s fastball and the mid-80s slider and changeup. But more importantly, his sinker and changeup gained movement. A lot of movement.

Each year from 2018-’20, his sinker dropped just under 20 inches on the way to the plate. Now, it’s dropping nearly 26 inches. It’s gone from being below average to being one of the sinkers that drops the most. (When asked why, last year, Gibson pointed both to mechanical changes and improved health that had finally given him a normal offseason to work out.)

Ditto the changeup – which has added about 5 inches of drop itself – and Gibson looks like a different pitcher, one who can do things like strike out the side against Miami.

The four-seamer that routinely got crushed is mostly gone. The curveball that didn’t curve is mostly gone. The remaining pitches do more interesting things, and the bat missing is suddenly vital in front of a weak Philadelphia defense. You may have thought you knew what kind of pitcher Gibson was, because he’d been showing it for so long. You can, perhaps, teach old pitchers new tricks.

Nestor Cortes, Jr., Yankees

What’s changed: His new primary pitch, a cutter

Here is our favorite leaderboard of the early season, showing strikeout rate leaders for all pitchers with at least 10 innings thrown.

45% – Cortes, NYY

45% – Carlos Rodón, SF

44% – Shohei Ohtani, LAA

44% – Michael King, NYY

40% – Andrew Heaney, LAD

That’s right, Cortes, owner of one of baseball’s great mustaches, the epitome of the “funky lefty,” the same Cortes who was once lost off waivers by the Yankees to the Orioles – and then, later traded away by the Yankees to the Mariners – has a higher strikeout rate than, well, anyone.

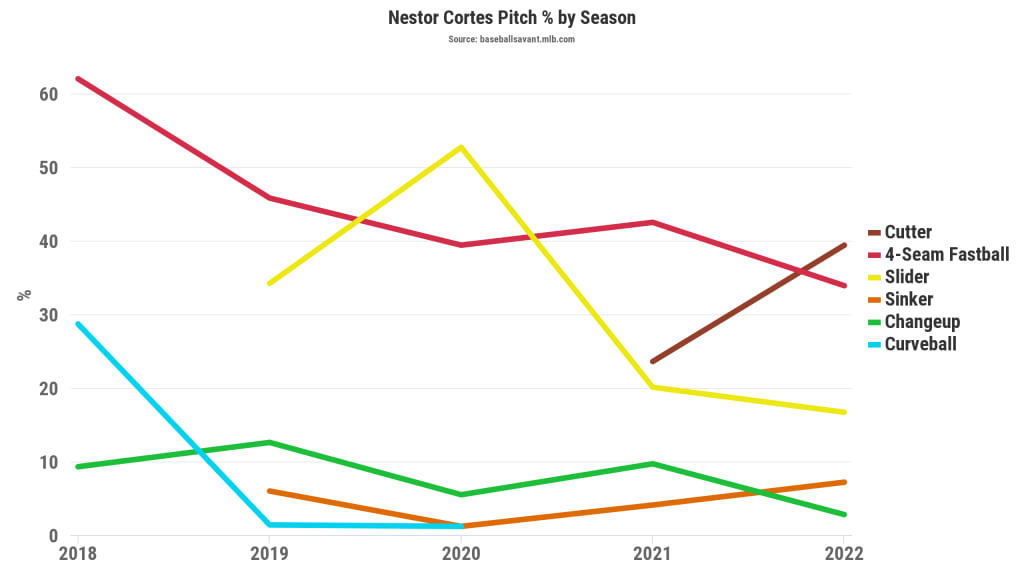

He has added a bit of velocity, though he’s still only up to 90.5 mph, so it’s not just about that (though he’s gained some rise on the pitch, as well). It’s mostly about the cutter, which he learned from former Major Leaguer Odrisamer Despaigne after the 2018 season but never really used until 2021.

It was a nice pitch for him last year, when he worked it in about a fifth of the time. This year, less than a year after first debuting it in a game, it's already his most-used pitch. It's changed everything.

Though it has above-average movement – two inches more break than cutters at his velocity, which is good – cutters are rarely known for their elite raw break. Instead, what he's done is use it to rely less on his just-OK slider, and to work off the four-seamer that now has that extra heat. It comes out just like his four-seamer does, and then drops more than a foot on the way to the plate.

We certainly don't expect Cortes to maintain a strikeout rate anywhere near this elite all year, but he also is not longer just the guy with the mustache, either. Cortes is the first pitcher in Yankees history with at least 25 strikeouts and fewer than 10 hits allowed in his first three games of the season. The Yankees, as you might have heard, have had some good pitchers.

Merrill Kelly, D-Backs

What’s new: The movement on his changeup

Kelly returned from a long stint in Korea before 2019 to prove that he could be an innings-eater in two of his first three seasons back in the States, around a 2020 season cut even shorter by a blood clot in his shoulder. Entering his age-33 season, however, Kelly was explicit about what he wanted to do, as he told MLB.com’s Steve Gilbert in March – he was going to improve his changeup.

"It's a pitch I have always prided myself on,” he said, “and I think the last couple of years, it hasn't been -- at least for me -- as good as it should be. And I'm happy with what I see from it so far."

He continued on with details.

“Sometimes it would cut, sometimes it would kind of just float. … I think I got a little too focused on trying to be too fine with it just because it wasn't doing what I thought it should do. And the focus this offseason was just to throw it in and see what I got. And then once it started showing more consistency, I was able to kind of fine-tune a little bit more."

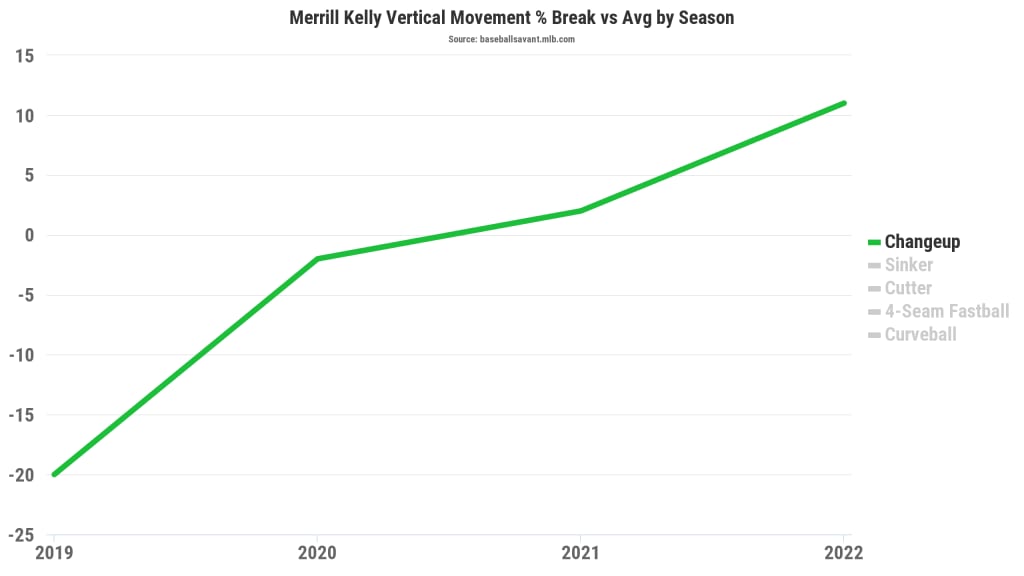

Mission accomplished. In Kelly’s first four starts, he's got a 1.69 ERA, striking out 22. The changeup that in 2019 was one of the weakest in terms of vertical movement is now above-average, going from six inches worse than average to three inches above average.

Unsurprisingly, the results are markedly better. In his first three starts, he threw it 54 times, allowing a mere one hit, while making it his second-most prominent pitch.

"I'm excited to see what it's doing so far," he said after beating the Padres in his first start of the season. His 29% strikeout rate through his first three starts is easily a career best.