Exactly 100 years ago today, on April 14, 1920, Babe Ruth played his first game as a member of the New York Yankees. It was a pretty innocuous debut, all things considered -- he went 2-for-4 with a couple of singles in a 3-1 loss to the Philadelphia A's, a team that had just finished a frankly mind-boggling 36-104 the year prior. Of course, that debut also changed the course of American sports and culture forever.

A century later, and that's still the scale at which Boston's sale of the Babe reverberates. The ripple effects are seemingly endless: our love affair with the home run, the establishment of one of the most iconic franchises in the world, redefining what it meant to be a star athlete in America, even a curse or two. But that doesn't mean things couldn't have turned out very differently. What if Ruth never wound up with the Yankees? What if the Red Sox had sent their star to Chicago instead?

That alternate reality isn't nearly as far-fetched as you might think.

From pretty much the moment he purchased the Red Sox in November 1916, Harry Frazee was at war with American League president Ban Johnson. Johnson had run the AL with an iron fist since its founding in 1901, and he was accustomed to deference from its long-time owners -- deference that Frazee, a brash new theater producer, didn't care much about.

The two sparred constantly, especially over Johnson's handling of the war-shortened 1918 season. (Johnson ordered the league shut down after America enacted its work-or-fight order, while Frazee, concerned over a wartime decline in theater revenue, helped lobby the government to keep the season going.) Frazee then unsuccessfully tried to have Johnson replaced by former U.S. president William Howard Taft, and before long, AL ownership had split into two factions: Frazee, White Sox boss Charles Comiskey and Yankees owners Tillinghast l'Hommedieu Huston and Jacob Ruppert on one side, and the so-called "Loyal Five" on the other.

Flash forward to the winter of 1919. Ruth has just announced that he wants his salary doubled to a league-high $20,000, not the first time he's clashed with Boston management. Frazee, feeling a financial squeeze due to decreased attendance at the ballpark and on Broadway (and looking to finance a new play of his, "No, No, Nanette"), decides to do the unthinkable and sell his best player. There's a problem, though: With the Loyal Five against him, the White Sox and Yankees stood as his only potential trade partners.

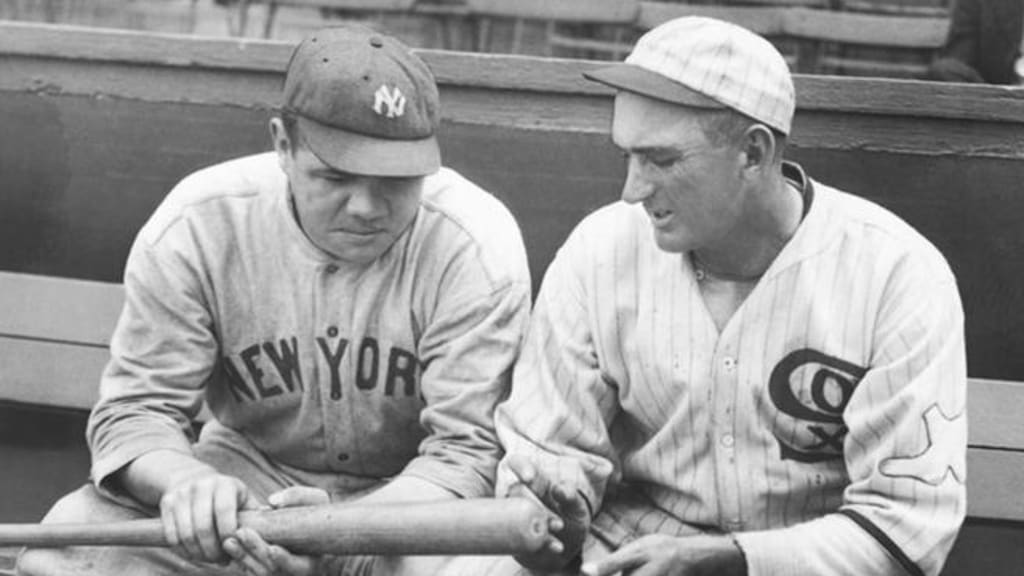

You know what actually happened next. Frazee sold Ruth to New York for a record sum of $100,000 (plus a $300,000 loan from Ruppert, secured by a mortgage on Fenway Park) and the Sultan of Swat was born. What you might not know is that there was another offer on the table: Ruth in exchange for $60,000 and Chicago's 32-year-old star outfielder, Shoeless Joe Jackson -- still eligible nine months before the Black Sox would be indicted by a grand jury.

What if Frazee, anxious about giving up a two-way star without any on-field return, decided to take the White Sox deal instead? It's almost impossible to fathom all the ways that hypothetical would've changed the baseball world, but here are six significant ones to get you started.

1. Jimmie Foxx becomes baseball's home run king

Let's get one thing straight: Babe Ruth once hit an opposite-field, walk-off homer that allegedly sailed over the Green Monster, across Landsdowne street and through a warehouse window -- he had home run power anywhere he played.

Still, it's hard to deny that he benefited at least somewhat from his new digs in New York. Fenway has always been tough on left-handed power, 314 feet down the right-field line but 402 to right-center in its original configuration, and even Ruth's Herculean fly balls sometimes struggled to find the seats. In 1919, his final year in Boston, he hit 20 homers in 286 plate appearances on the road -- and just nine homers in 257 plate appearances at home.

During Ruth's first three years with the Yankees, on the other hand, he played his home games at the Polo Grounds -- a park that, because of its notorious bathtub shape, played impossibly deep to center field ... but just 258 feet down the right-field line.

In 1923, the Yankees moved across the river to the Bronx, to a stadium literally made with Ruth's uppercut swing in mind.

Had the Babe gone to the White Sox, though, the record books likely look a bit different. Ruth still becomes the preeminent slugger of his day, the face of the new live ball era and the man who showed hitters and fans what was possible if you swung for the fences (just a friendly reminder that he hit 54 dingers in 1920, while no one else hit more than 19). But with Comiskey Park playing 362 feet down the line in right, his numbers are possibly a little less gaudy -- he still sets the all-time record, retiring at around 640 or 650, but he never quite reaches that iconic 60-homer mark in 1927, instead settling for 56 or 57.

Which opens the door for Foxx, whose 58 dingers in 1932 become the new single-season record, later tied by Hank Greenberg in 1938. It's Foxx's and Greenberg's mark, not Ruth's, that Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris chase in 1961 -- and without the ghost of the Babe looming over him, fans are far more charitable when Maris hits homer No. 59 in game No. 154.

2. The Yankees become just another contender ... for now

New York's rise from afterthoughts to icons wasn't just about Ruth's contributions on the field. It was about the entire ecosystem he enabled: the sparkling new ballpark in the Bronx, the record number of fans who flocked to it, the record revenue those fans produced and the unparalleled scouting network (and signing bonuses) that revenue paid for.

The Yankees simply had unseen levels of resources at their disposal, and it resulted in an unseen flow of talent -- guys like Tony Lazzeri, Earle Combs, Bill Dickey, Lefty Gomez and Joe DiMaggio, all of whom were signed from then-independent Minor League clubs in every corner of the country. (Not to mention the flurry of trades in which New York more or less bought players from cash-strapped teams like the Red Sox.)

The team had to identify that talent before signing it, obviously, and de facto general manager Ed Barrow and field manager Miller Huggins were astute baseball minds. But without Ruth, they would've been operating on the same level as every other club. Barrow and Huggins would've kept the Yankees in the hunt consistently -- they'd already started building the team into a contender before Ruth arrived, jumping from 60-63 in 1918 to 80-59 in 1919.

But they'd be just that: contenders, like the A's and Senators and Indians, rather than an overwhelming force. ... That is, until George Steinbrenner decides to buy the team, at which point New York embarks on its 1970s dynasty as usual.

3. The White Sox become Chicago's team

It's tempting to simply say that Ruth would turn the White Sox into the Yankees, but that's not quite right. New York's supremacy was the result of a perfect storm: the greatest power-hitter of all-time in a park tailored to his strengths in a city on the verge of becoming the cultural and economic capital of the country at a time when baseball rules were far less conducive to league-wide parity. (Before the Draft and affiliated farm systems, the Yankees' financial might made them so dominant that, in 1940, MLB instituted a rule stipulating that no team could trade with the team that had won the pennant the previous year.)

Ruth wouldn't have put up quite the same numbers in Chicago, and he wouldn't have captured the nation's imagination in quite the same way. He would have led to record attendance numbers and revenue, though, as baseball's first slugger calls Comiskey Park home.

The White Sox would've received even more help from Boston. In the three years after selling Ruth to the Yankees, New York acquired 14 more players from the Red Sox -- including basically their entire starting rotation -- as Frazee desperately searched for ways to fulfill his debts. In our universe, it's the White Sox who have cash to burn, and they use it to replenish their roster after Shoeless Joe and the Black Sox are banned for life.

That boost buys them decades of contention, and it vaults them over the Cubs in the city's pecking order.

4. Lou Gehrig goes down as an all-time great ... with the Red Sox

OK, this is admittedly a bit of a bank shot, so allow us to explain.

Following a sophomore season at Columbia in which he hit .444, launched a home run clear out of South Field and even put up a 17-strikeout performance on the mound, the Yankees were so smitten with Gehrig that they convinced him to forgo his final two years of school to go pro. He kept on raking in the Minors, earning cups of coffee with the Major League club in 1923 and 1924, but he was blocked by some guy you may have heard of by the name of Wally Pipp. (Which didn't seem so crazy at the time: Pipp hit .329 and finished eighth in AL MVP Award voting in 1922.)

For as solid as Pipp had been, however, he turned 32 prior to the 1925 season, and with his best years behind him the Yankees started searching for an upgrade. Gehrig was one possibility, but he was still unproven at the big league level, and New York was looking to win right now. So the team proposed a trade: Gehrig would be sent to Boston in exchange for Phil Todt, a young first baseman who'd just hit a respectable .262 as a rookie.

By all accounts, new Red Sox owner Bob Quinn (Frazee finally sold the team in 1923) seriously considered the deal before finally turning it down. The most commonly suspected reason? He was wary about doing business with the Yankees, determined not to get fleeced in the same way his predecessor had.

Had Ruth been sent to Chicago, there would be no particularly bad blood between Boston and the Yankees, and maybe Quinn feels comfortable pulling the trigger and acquiring Gehrig. The Iron Horse becomes an instant star, one of the greatest hitters ever, but he'll need a different nickname -- being the heart of the Red Sox lineup results in a bit more wear and tear, and as a result he misses a few games as he hits his 30s. Gehrig plays in 1,259 consecutive games, allowing Everett Scott to narrowly retain the record until he's passed by Cal Ripken Jr. (Shoeless Joe Jackson's fall after just one year in Boston, meanwhile, turns the Curse of the Bambino into the Curse of the Black Sox.)

5. The Braves become the team of the '90s

Of course, no Ruth means no House That Ruth Built, and that has some pretty far-reaching consequences. The Yankees eventually move out of the Polo Grounds and into a ballpark of their own -- they've carved out a niche for themselves in the New York baseball landscape after winning a couple of pennants in the '20s and '30s -- but without the Babe, the Yankees decide to outfit their new home with pitching-friendly dimensions to help out their rotation.

Steinbrenner keeps those dimensions intact during the renovations in the 1970s. That means no short porch -- and without the short porch, Derek Jeter's fly ball in Game 1 of the 1996 ALCS falls harmlessly into Tony Tarasco's glove.

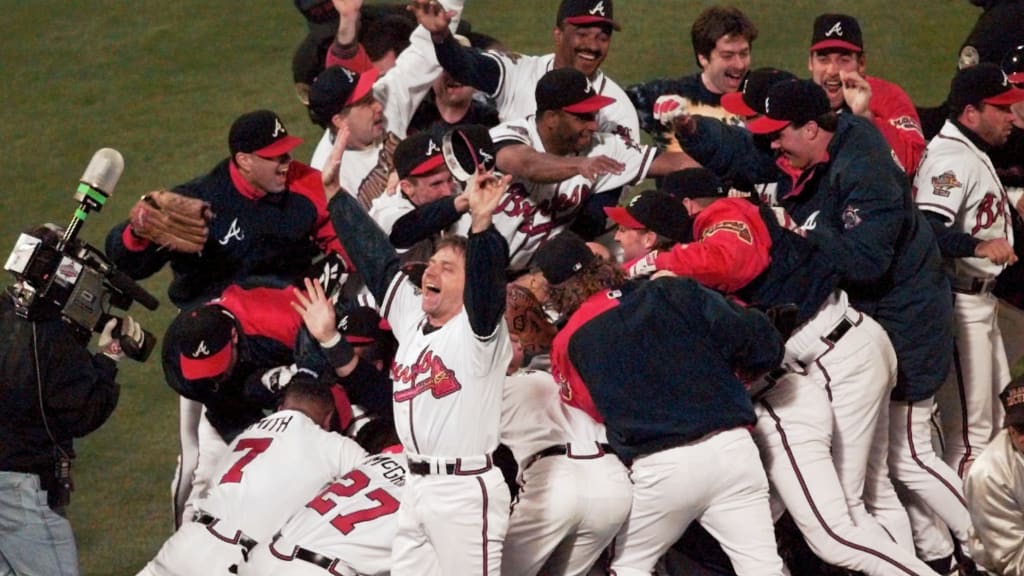

The Orioles win Game 1 and take a 2-0 lead back to Baltimore, where they close out the series in five. The Yankees are denied their long-awaited renaissance, while the O's head to their first World Series since 1983 ... only to fall to Maddux, Smoltz, Glavine and the defending-champion Braves.

Steinbrenner, furious at his team flaming out in the postseason, decides to go big, breaking the bank to sign free-agent slugger Albert Belle that winter and flipping catching prospect Jorge Posada to the White Sox for pitcher Roberto Hernandez. Belle demands a raise after a 45-homer season in 1997, Steinbrenner refuses, and the ensuing drama causes New York's clubhouse to unravel. The Yankees don't make it back to the Fall Classic until 2001, while the Braves add another title in 1999 to officially become the team of the '90s.

6. Mickey Mantle helps the Dodgers stay in Brooklyn (and Kevin Durant signs with the Knicks)

Want to know to what extent Ruth enabled New York to build a scouting Death Star? Look no further than Tom Greenwade.

Greenwade spent years as Branch Rickey's top scout with the Dodgers, the man entrusted with evaluating Jackie Robinson before he broke baseball's color barrier. He held that role until 1949, when the Yankees simply made him an offer he couldn't refuse -- more than tripling his salary, from $3,600 to over $11,000, making him the highest-paid scout in baseball.

It turned out to be money well spent. Greenwade inked more than his share of big leaguers over 15 years with New York, from Elston Howard to Bobby Murcer, but his greatest coup was one of his first: In the summer of 1949, behind a dusty grandstand in Baxter Springs, Okla., he signed Mickey Mantle for $1,500.

In our world, though, the Yankees don't have the kind of money to lure Greenwade away from Brooklyn. Mantle becomes a Dodger, winning the NL MVP Award in 1952, and his star power -- combined with a couple extra World Series victories over New York -- helps Walter O'Malley convince New York development czar Robert Moses to hand over a plum plot of land on the corner of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues. The Dodgers finally get their new stadium and stay in Brooklyn for good.

Instead, it's the Giants -- now a definitive third in the city's pecking order thanks to roster mismanagement and a decaying Polo Grounds -- who move out to L.A., while an expansion team opens in San Francisco. The Dodgers fill the NL-shaped hole in New York's heart, and the Mets never come to Queens, meaning we all have to live in a world in which Mr. Met no longer exists.

But baseball is not the only sport affected by this game of musical chairs. With Brooklyn no longer in need of its own sports franchise (and a new Ebbets Field occupying the spot where Barclays Center would eventually be built), the Nets never make the trek across the river from New Jersey, settling for a new arena in Newark. The bright lights of the Big Apple still call to Kevin Durant, though, and he becomes the star who finally chooses the Knicks. (Look, it's my alternate reality. I can dream, can't I?)