The wildest game in recorded Major League history was a mere one-run victory. It was also an absolute mess.

The game featured 11 pitchers, and all 11 of them allowed at least one run -- no one made it through unscathed. Five of them suffered a blown save, to this day still tied for the most ever. Fourteen of the 18 half-innings saw a run cross the plate. The visitors hit six home runs, including three on back-to-back-to-back pitches in the second inning, had a lead with two outs in the ninth inning -- and still lost.

There were seven lead changes and 38 hits, including 10 homers. The home team’s second baseman stole six bases, tied for the most ever, including when he stole second, third, and home in the third inning. The "winning" pitcher, such as he was – perhaps "surviving’ pitcher is more appropriate -- turned a two-run lead into a one-run deficit in his lone inning. At four hours and 20 minutes long, it was, at the time, the longest nine-inning game in National League history.

It was, as you’d expect, played at Coors Field. Before the humidor was installed. On a warm 81-degree summer day. With the wind blowing out to dead center at 10 mph. In a season that was already one of the highest-slugging years in history.

It was June 30, 1996. The Rockies beat the Dodgers, 16-15, capping a four-game series in which 85 runs were scored between the two teams. That doesn’t begin to describe it.

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” said Dodgers third baseman Mike Blowers to the Los Angeles Times.

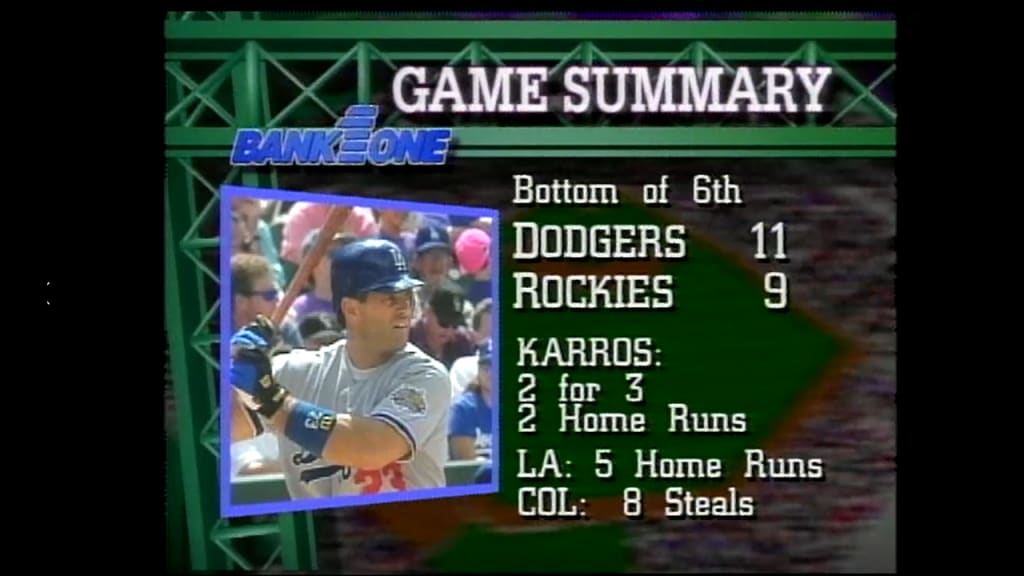

“As much as I’d like to hit here,” said Dodger first baseman Eric Karros, who’d just popped two home runs, “I don’t know I’d want to play 81 games here. I’d probably have a nervous breakdown. I’d have an ulcer. I couldn’t take it.”

He wasn’t the only one with health concerns.

“Hopefully,” wrote the Associated Press, “Tommy Lasorda's doctors didn't let him watch this one.”

Just a week earlier, the long-time Dodger skipper had suffered a coronary issue that ultimately ended his managerial career a month later, leaving Bill Russell on his first road trip as the team’s interim manager. Welcome to the job, Bill.

Is this all hyperbole? Sure, perhaps. But all these years later, when we attempted to answer the question of “what was the wildest game in baseball history,” this is what topped the list. Those who were there that day couldn't have known about the historical relevance, or even the metrics we'll use. But just listen to them talk. They could feel it.

What makes a game exciting? Generally, you think of two things. First, it has to be close, not a blowout. The outcome has to be in doubt for most or all of the game. Second, the game has to be full of action without getting out of hand. The first requirement, a close game, disqualifies messes like Boston routing Florida, 25-8, back in 2003. A lot happened, sure, but the Red Sox put up 14 runs in the first inning, which basically ended the drama. Everything after that was just window dressing, eight innings of watching a 99% assured outcome.

The second requirement, that there be plenty of action, disqualifies any number of tight 0-0 or 1-0 games which might be tightly-played and are certainly close, yet don’t exactly have a lot of highlight-reel moments. For some fans, a 1-0 game into the ninth is high drama; for others, it’s boring. Either way, it’s not what we’re looking for here.

No, what we’re after is a game that has both. We want action, and we want a game where the late-inning plate appearances still actually matter. To that end, we turned to a few modern metrics in win probability, which expresses the impact of a specific play on the outcome of a game, and leverage index, which shows how important each plate appearance is given the situational context of the moment.

By creating a formula to grade each plate appearance of a game on the basis of both win probability and leverage index and combining them, we were able to create a list of games that were, for lack of a better term, most. This game at Coors in 1996? It was the most.

(Reliable play-by-play data goes back to 1974, which admittedly is not all of baseball history. That said, it’s also somewhat difficult to expect a previous game outside of pre-humidor Coors Field would rate any higher. Entertainingly, a 1998 Rockies game at home was second-wildest by this measure, and a 2016 Rockies game at home was fourth. Six of the top ten games, including the postseason, took place at Coors Field.)

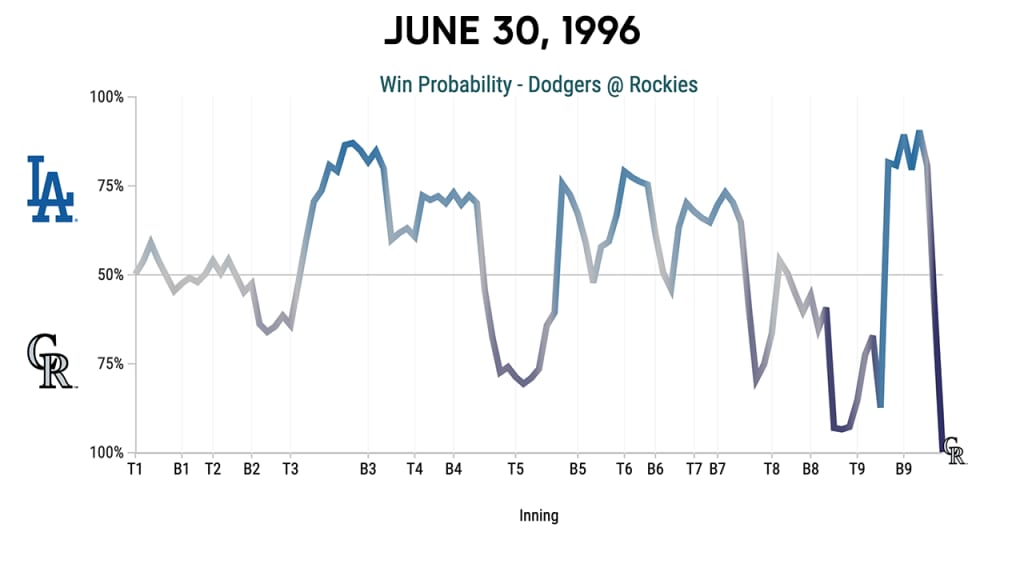

If this one felt like a heart attack -- sorry, Tommy -- then the win probability chart looked like one, too.

At the end of 21 separate plate appearances, the Dodgers had a win probability of 70% or higher. Four times, it was north of 80%, topping out at an 88% likelihood of winning in the bottom of the ninth inning, when they held a one-run lead with two outs and a runner on first. Eighty-eighty percent, as they say, is not 100%. Especially not in Coors Field, not in 1996, where it’s difficult to overstate how high-flying the offense was.

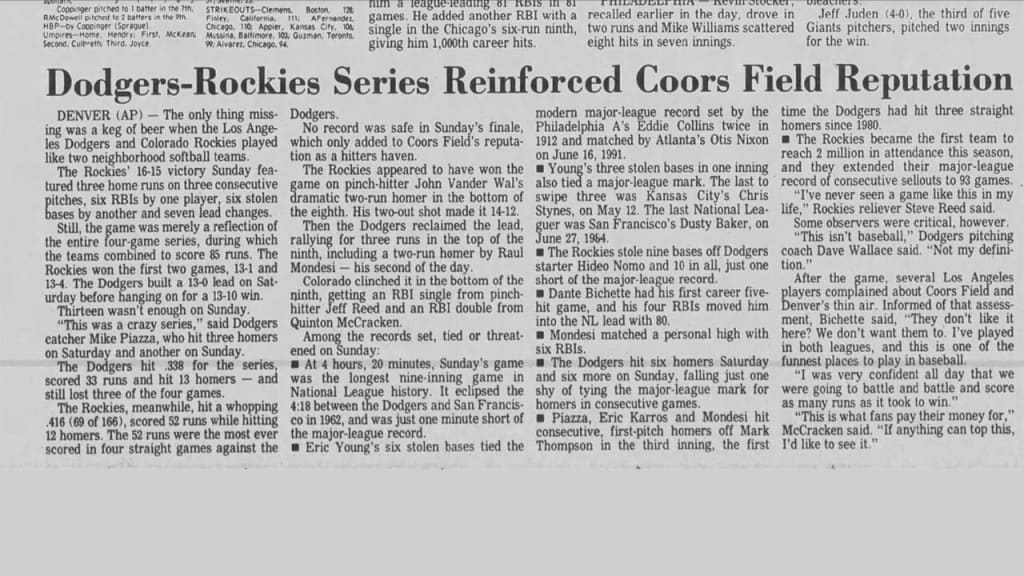

As MLB.com’s Paul Casella wrote in 2022, “Teams combined to post a 7.06 ERA at Coors Field in 1996, which was not only the highest in the Majors that season, but it remains the highest ERA for any individual ballpark in a single season in Major League history.”

16-15, by 1996 Coors standards, was practically a pitchers' duel.

It’s one thing to look up the numbers and read old newspaper clippings. It’s another thing entirely to watch the entire game, so that’s exactly what we did. We dug up the entire broadcast from Colorado’s KWGN-2 -- Denver’s 2! -- commercials and all, to see if the broadcasters slowly descended into madness. Join us on a journey.

First inning

Welcome to 1996. A young Chris Rock is trying to sell you 1-800-COLLECT. The game broadcast graphics are exquisite.

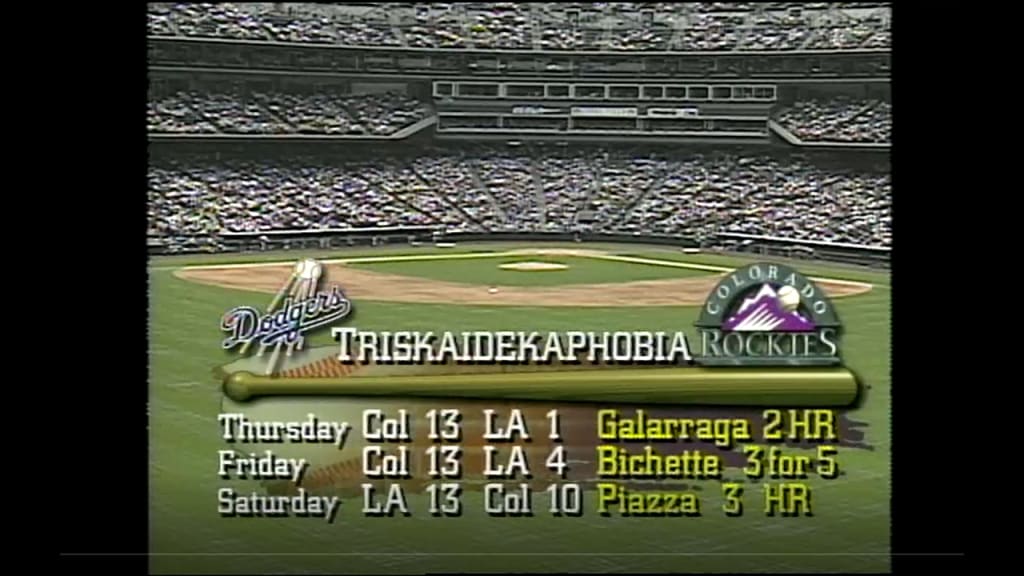

Rockies broadcasters Dave Armstrong and Dave Campbell would like you to know that the “first to 13 wins this one here today,” pointing out that the winning team had scored exactly 13 in each of the first three games of the series. They should have taken the over. We can neither confirm nor deny that this is the first time the word "triskaidekaphobia" had ever appeared on-screen during a baseball game.

Ultimately, this was a surprisingly tame start, with no runs scored on either side in the first inning off Mark Thompson or Hideo Nomo. Remember above when we said only four of the 18 half-innings were scoreless? Somehow, three of those were the first three, though “scoreless” isn’t the same thing as “clean,” particularly when Ellis Burks stole second base. That was the first of 10 steals allowed, and it was a team effort. Nomo was slow to the plate and Mike Piazza’s throw, as Campbell noted, “wasn’t in the zip code. That ball was headed to Ft. Collins.” His geographic accuracy is spectacular.

End of the first: Dodgers 0, Rockies 0

Win probability: Rockies 54%

Second inning

Thompson -- who had a career 6.11 ERA as a Rockie, the highest in team history of anyone who threw at least 250 innings -- manages to get through two innings scoreless, though it wasn’t exactly pretty as he worked around three walks.

“He’s certainly not in the comfort zone right now,” said Armstrong. Just wait.

In the bottom of the second, Nomo gets Andres Galarraga to ground out before leaving a splitter that didn’t split for Vinny Castilla’s 17th homer of the season. It occurs to us at this point that Thompson escaped the top of the second in part because Nomo put down a sacrifice bunt, and Nomo escaped the bottom of the second in part because because Thompson struck out. Just imagine what this game might have been like today, if pitchers batting hadn’t combined to make eight outs?

End of the second: Dodgers 0, Rockies 1

Win probability: Rockies 60%

Third inning

If you’re wondering when things were going to go off the rails, then the answer is “right now.” Thompson gets Delino DeShields to pop out, but then allows back-to-back-to-back home runs on three consecutive pitches to Piazza, Karros and Raul Mondesi.

Campbell: Better try something different, Mark. Maybe throw one in the dirt or something.

It had to get better from there, right? In the strictest sense of "better," yes, but going double-single-flyout-double-single to the next five batters isn’t exactly ideal -- that second double was by Nomo, who had an OPS+ that year of -7, to really pour salt in the wound. Suddenly the Rockies are down, 5-1, and Thompson’s day is done after 2 2/3 innings.

But we’re just getting started. In the bottom of the third, Eric Young Sr. singles on a line drive to left field. He then steals second base, third base, and then, on a busted pickoff attempt of Burks at first base, he steals home. He’s the first National Leaguer to do it since Dusty Baker back in 1984.

One pitch later, Dante Bichette does it the easy way, hitting a two-run homer off Nomo. It’s now a one-run game. There’s six more innings to go. Nomo somehow strikes out three in the inning around all of this mess.

“Here we go again,” exclaims Armstrong.

“I’m not sure 13 will actually be enough today,” suggests Campbell. You’ve got that right.

End of the third: Dodgers 5, Rockies 4

Win probability: Dodgers 61%

Fourth inning

Roger Bailey, who relieved Thompson in the third, faces the heart of the Dodgers' order, allows Karros a second solo home run and walks Blowers, but otherwise escapes without further catastrophe. That counts as a highly successful inning, so far as this afternoon is going to go.

In the bottom of the inning, Nomo has a rough time, though it’s not entirely his fault, at first. After a leadoff popout from Jayhawk Owens, Quinton McCracken grounds out to second and DeShields bobbles it for the team’s second error of the day. Nomo ends up allowing run-scoring doubles to Walt Weiss and Burks, then, after a wild pitch moves Burks up, a Bichette single scores the fourth Rockies run.

Eight Rockies come to the plate. Four runs score -- all unearned, thanks to the DeShields error -- and the Rockies steal four more bases off the Nomo/Piazza pairing.

“I love this game. I really do. This is fun,” notes Armstrong. Will he still think that in two more hours?

But, extreme 1996 strategy warning incoming: Nomo throws 44 pitches in this inning alone. He’s now allowed seven hits, three walks, eight runs, eight stolen bases, a wild pitch and at least one other wild pitch saved by Piazza. The broadcast has noticed his velocity has dropped. Lefty Joey Eischen starts moving around in the bullpen, but Nomo is allowed to complete the frame. While it's true the bullpen was taxed in a wild series in Denver, it's also true the previous night's starter, Ismael Valdes, had completed seven innings.

So despite Nomo's relative ineffectiveness here, he's allowed to stay in, which is about to have a secondary effect ...

End of the fourth: Dodgers 6, Rockies 8

Win probability: Rockies 72%

Fifth inning

… because not only is Nomo still on the mound, he’s allowed to bat, striking out.

Too bad for the Dodgers, too, because Bailey walks Fonville and allows back-to-back singles to DeShields and Piazza, drawing the Dodgers within one. New pitcher Darren Holmes immediately walks Karros and allows Mondesi to triple over McCracken’s head with the bases loaded. Holmes is routinely taking 30 seconds between pitches. We welcome the pitch timer.

In the bottom of the inning, Nomo is still out there, and guess how this goes: Castilla singles, Owens walks, McCracken singles. The bases are loaded. There are no outs. Nomo is still in the game. That he allows only one run to score -- on a fielder’s choice -- as he starts his fourth time through the lineup is something of a minor miracle, though Young swipes his fifth base of the day. The broadcasters are discussing the 1911 Yankees' single-game stolen base record.

Through five, we’ve seen 19 runs. There are a dozen yet to come.

End of the fifth: Dodgers 10, Rockies 9

Win probability: Dodgers 64%

Sixth inning

Campbell is absolutely on it: “The Rockies have to prevent the Dodgers from scoring 15 or 16.” They don’t, but they win anyway.

Never has a more accurate description of mid-'90s Coors Field baseball been uttered. While we are making jokes, Todd Hollandsworth welcomes new pitcher Steve Reed with a solo home run to right field.

“This is a Coors Field home run,” says Armstrong, as they catalog which of today’s blasts were "legit" or not. We’re six years away from the humidor.

In the bottom of the sixth, Burks’ solo rocket to center field draws the home team back within one, though after Chan Ho Park, who has mercifully relieved Nomo, allows the next two to reach, a double play avoids further damage.

Campbell: I can only think of the immortal advice of Curtis Leskanic, who said, “My only advice to the other team is that when they come to Coors Field, tell the other team to pack a lunch, because it’s going to be a long day.”

We’re three hours into this one. We’re nowhere near done.

End of the sixth: Dodgers 11, Rockies 10

Win probability: Dodgers 67%

Seventh inning

We pause here to give respect to an absolutely beautiful inning in the midst of complete chaos. Reed throws seven pitches and gets three outs, all fly balls. Armstrong, correctly, sounds like the Rockies just won the World Series. “Would you believe this, folks?!??"

Meanwhile, Dick Ruppel of the Rocky Mountain Sod Foundation appears to present an offering of Coors Field sod to take on the road, in hopes of bringing some of that magic along with the team as they travel. As we’ve written about many times, there’s a bit of a Coors Field hangover in that the effects hurt Rockies hitters on the road, even as it boosts them at home. Perhaps this is where the curse began?

But there’s still a baseball game to be won, and new Dodger pitcher Scott Radinsky comes ever so close to hanging on to the lead, retiring the first two he faces and then inducing an inning-ending grounder to short. Or at least it would have been inning-ending, had Greg Gagne not booted it, which then leaves Radinsky out there long enough to allow two runs on three consecutive singles, coughing up the lead.

The Dodgers end up allowing 16 runs today, and only eight are earned.

End of the seventh: Dodgers 11, Rockies 12

Win probability: Rockies 71%

Eighth inning

Leskanic isn’t just a dispenser of advice, he’s a pitcher as well, though he enters and immediately allows back-to-back singles before Hollandsworth ties it with a sacrifice fly. We pause as Mondesi attempts to shake off a leg injury suffered trying to beat out his leadoff hit. It didn’t look good. He remains in the game, though it doesn’t look great.

So, of course, the first two balls of the bottom of the inning are hit to him. The first, he collects easily. The second, well:

That’s the fourth error of the day for the Dodgers, and if you’re wondering whether giving away free outs on a warm day at Coors Field is going to come back to bite you, well, you already know the answer. Antonio Osuna gets McCracken to ground out for the second out, which brings pinch-hitter John Vander Wal to the plate. It’s 12-12. The count is 3-1. It’s long gone.

“Baseball now has the subtlety of Australian Rules Football,” sighed ESPN’s Keith Olbermann on SportsCenter later that night, recapping the madness. Young follows up with a single, which is meaningful only because he then immediately steals his sixth base off yet another wild Piazza throw, tying a Major League record. That he doesn't end up coming around to score makes him notable by these standards.

End of the eighth: Dodgers 12, Rockies 14

Win probability: Rockies 91%

Ninth inning

So now it’s the ninth inning. The Rockies, based on win probability, have a 91% chance of winning, based on being the home team up two runs at this point in the game. It’s over, right?

Bruce Ruffin, the new Rockies pitcher, is going to get the "W" here. But realize how he gets there: Single, wild pitch, run-scoring single, runner advances on catcher throwing error, groundout, strikeout, lead-blowing homer, strikeout. He enters with a two-run lead and leaves with his team down one. Definitely a winning performance.

Middle of the ninth: Dodgers 15, Rockies 14

Win probability: Dodgers 75%

This leaves the save opportunity to Dodgers closer Todd Worrell who was, for about a decade in the late 1980s and mid 1990s, one of the most dominant closers in the game. He was the 1986 Rookie of the Year, and even at 36 years old, he was so good in 1996 that he was an All-Star and finished fifth in the Cy Young vote. He even got some down-ballot MVP support. He’d pitched twice at Coors earlier in the series and emerged unscathed.

He was extremely good, is the point.

Worrell got Burks to pop out for the first out, then, after a Bichette single, gets Galarraga to pop out. At this point, the Dodgers, by virtue of being up one in the ninth with two outs and a runner on first, are sitting on an 88% win probability. It’s the high point of the game for Los Angeles.

Castilla’s single puts men on the corners. Up steps pinch-hitter Jeff Reed, a relatively light-hitting catcher who had a .621 OPS in parts of a dozen previous Major League seasons. Campbell points out that we’re four hours and 15 minutes into the game. Reed’s game-tying single to left sets up McCracken’s game-winning double. Go crazy, Coors Field. Go crazy.

“In this ballpark, anything can happen,” Worrell said. “I don't think the game is enjoyable when it's played here."

McCracken, unsurprisingly, disagreed. "This is what fans pay their money for. If anything can top this, I'd like to see it."

"I've played in both leagues," echoed Bichette, "and this is one of the funnest places to play in baseball."

In 1996, Bichette had a 1.059 OPS at home and a .697 OPS on the road. No wonder he found it so enjoyable.

"We just were not going to be denied today," Rockies manager Don Baylor said. "All I knew was we had the last at-bat. If we stayed close, their guys out of the bullpen were not going to contain us.”

“Of course, we couldn't stop them, either."

They could not. No one could stop anyone. Eventually, the innings just ran out. As a capper, two-and-a-half months later, Nomo returned to Coors Field for the first time since the June catastrophe. He threw a no-hitter. Come to think of it, maybe that's the wildest game in Major League history.