If it seems like each season there’s an absolutely out-of-nowhere reliever who pops up to dominate, there almost always is. But even that realization won't prepare you for how far off the radar this year's entry was, because he A) had an 11.50 career ERA entering the season; B) didn’t even make his own team’s Opening Day roster; C) wasn’t listed among that team’s Top 30 prospects; and D) was acquired seemingly as a throw-in to complete what was at the time a considerably unpopular trade in his new hometown.

It’s not exactly the traditional recipe for success, is it?

Yet all of those facts accurately describe Baltimore’s Yennier Cano, who has faced 64 batters this year and sent 59 of them walking back to the dugout. He’s not allowed a run, or even a walk. Three of the four hits he's allowed have traveled fewer than 100 feet, and the fifth baserunner, Justin Turner, earned it by taking a 94 MPH fastball off the elbow. He has the second-highest ground-ball rate in the game to go with his 23/0 K/BB ratio. He is atop the Statcast expected outcomes leaderboard.

It is pitching just about as well as pitching can be performed. It is dominance in a way that cannot be faked or lucked into. It’s elite pitching on a notable scale. If you go back to the beginning of reliable data for this in 1974, allowing just five baserunners in a span of 64 batters is coming up right upon as good as anyone’s ever done -- and there are some pretty interesting names among the ones who have done better.

Fewest baserunners allowed in any span of 64 PA, 1974-2023

(Single-season only. Overlaps excluded.)

- 4 - Sean Doolittle, 2014

- 4 - Koji Uehara, 2013

- 4 - Bobby Jenks, 2007

- 4 - Craig Kimbrel, 2012

- 4 - Rafael Betancourt, 2011

- 5 - several tied, including Cano, 2023

It is, again, coming from a pitcher nearing his 30th birthday with absolutely no track record of Major League success as recently as one month ago.

So: Why should we believe in it? Or, perhaps more relevantly for an Orioles club that was a mere 4.5 games behind the red-hot Rays in the American League East entering play on Tuesday: How did they manage to do this?

The Cano that Baltimore acquired from the Twins last summer certainly didn’t look like this.

A year ago today, Cano was an up-and-down Minnesota depth arm, one who had allowed 14 runs in 10 games for the Twins in the Majors and who had been optioned back to Triple-A by the time Baltimore made the somewhat surprising and hardly well-received decision to trade All-Star reliever Jorge López to the Twins, despite his role in their sudden resurgence.

Cano then allowed 10 runs in seven games for Baltimore’s Triple-A Norfolk affiliate, came up to allow seven runs in 1 2/3 innings to Boston on Sept. 10, went back down, then came up to allow runs in each of his final two games of the season. At the end of the year, he had that 11.50 ERA next to his name, and if you’d looked up “highest career ERA in post-1947 history among pitchers with at least 15 innings thrown,” you’d have found his name in the top 10 – or bottom 10, depending on how you want to look at such things. Many of those pitchers never get another shot, which is why you don't remember Matt Kinzer, Sid Schact, or Pete Craig.

When the Orioles released their 2023 Opening Day roster, Cano understandably wasn’t on it, despite the absence of veteran righties Dillon Tate and Mychal Givens due to injury, and so back to Norfolk he went.

So to say that “you couldn’t have seen this coming” somewhat undersells the point. It’s not so much that we all missed baseball’s next big thing. It’s that there wasn’t, at least publicly, a whole lot to miss. Cano went from “one of the least effective pitchers in the game” to “a run of excellence you’ve never seen before.”

OK, so: how?

“I sit in the dugout and I can’t tell his fastball from his breaking ball,” Orioles bench coach Fredi González told MLB.com’s Jake Rill, “unless I look at the miles per hour, because everything is going down and hard, and so it’s hard from the side view, the depth of it, it’s hard to see what it is. Until you look up and you’re like, ‘Oh, that’s a changeup,’ because it was 91, or, ‘That’s a sinker,’ because it was 97. But he’s been able to repeat his delivery. He’s been really good.”

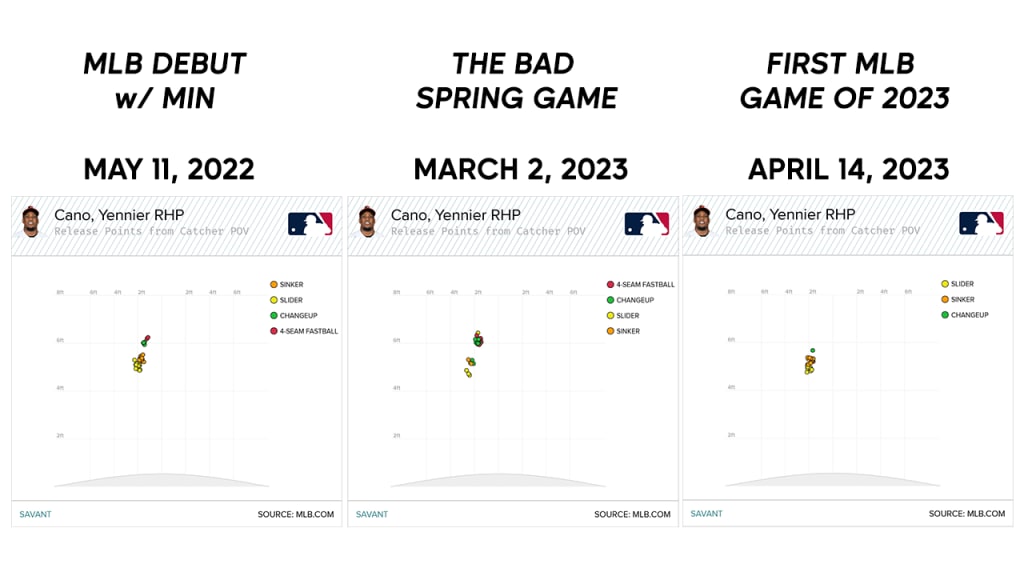

That effect – of not knowing which pitch is which – is visualized quite well here:

“I can’t even describe it,” Orioles manager Brandon Hyde said at the end of April. “Has anybody ever seen that? Nope, so it’s indescribable. He’s up there with a ton of confidence, throwing a ball that’s moving two feet down at 95 mph, with a good changeup also. You take your chances on probably either a ground ball or punchout. He’s been enormous for us.”

He's right about that last part -- 52 of Cano's 64 plate appearances (82%) have either ended with a ground ball (29) or a strikeout (23) -- but if anything, Hyde undersold it with “moving two feet down,” because it’s more than that. Cano’s sinker drops 33 inches on the way to the plate, which is nine inches more than the average sinker at his velocity. (That gap, the “nine inches better than average” number, is the largest of any sinker in the game.) It’s a huge change from last year, when he got 27 inches of drop at the same velocity.

“I think working in and through the strike zone has been the biggest difference. I think that’s been the key for me this year,” Cano said (via team interpreter Brandon Quinones) at the end of April. “I know my stuff is good. Everyone tells me my stuff is good, so it wasn’t a matter of that. It was just a matter of finding the strike zone and finding a way to work through it.”

But there’s also evidence that a change Cano made on his own in Spring Training is playing a big part in this. On March 2, he was the sixth Baltimore pitcher to face an early-spring Tigers lineup, and it didn’t go well, as he allowed four hits and four runs while failing to complete an inning. He didn’t appear in a game again for 10 days but allowed just two hits over five remaining spring appearances.

What happened? As he recently told MASN, he’d been throwing from two arm slots to that point, and afterwards, he decided to ditch the more over-the-top-one and throw only from the lower slot. If you compare his first MLB game from last year, with the bad spring game against Detroit, to his first MLB game of this year, you can absolutely see what he meant. Aside from one changeup, there’s a solid single release point where there used to be two.

What’s also happening, likely, is an example of “seam shifted wake,” or the ability to gain extra movement just by manipulating the seams themselves. Cano hasn’t added more spin (he’s lost some, actually) or thrown it more efficiently (less so, actually). But last year, the spin axis of that sinker out of his hand was at 2:30 on a clock, from a pitcher’s point of view, and arrived at 2:45 – which is to say, barely any difference. This year, it’s still coming out of his hand at a 2:30 direction, yet it arrives at a 3:30 direction. That’s a wildly oversimplified way of saying: The spin axis changes on the way to the plate and it causes some extra and unexpected movement to confound the batter.

Just look, for example, what it did to a quite productive hitter in Vinnie Pasquantino, alongside some other visuals of Cano's sinker making good hitters look bad.

What he’s done, then, is to take that sinker – the one at 95 mph that drops 33 inches with 18 inches of break – and make it look exactly like the changeup, just with a 5 mph velocity difference. It's not an easy task for a batter to hit against that, especially when the sinker comes to the plate a full foot higher than the changeup does (2.5 ft. vs. 1.5 ft.) and when there's that good-enough-not-great slider out there as well. (The changeup has yet to allow even a single hit, yet.)

It should be pointed out, again, that Cano has exactly one month and 15 games of Major League success behind him. It’s not that he’s now guaranteed to spend years as an elite Major League reliever, because he'd hardly be the first popup arm to look great for a month and disappear. It's that what he's done so far is for real, for reasons you can clearly see. It's not just good luck, or a hot streak. It's quite simply outstanding pitching from an incredibly unlikely source. It's done a lot to make that López trade look different. It's done a lot to keep the Orioles in a race for first place.