Two years ago, Yoán Moncada did something highly entertaining and all but certainly unrepeatable -- for most hitters, anyway.

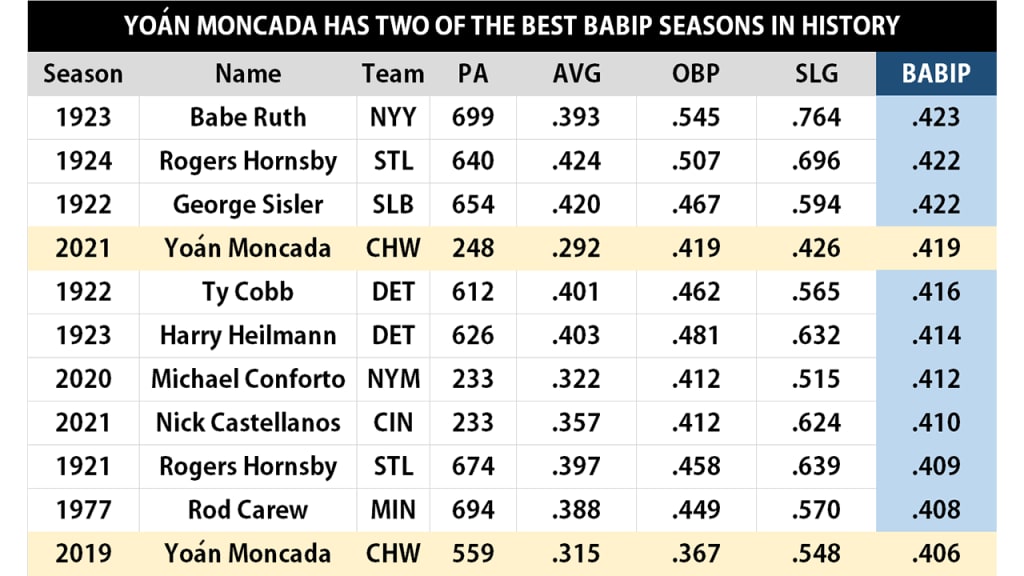

As part of a breakout .315/.367/.548 season in 2019, more than 40 percent of the non-homer balls Moncada made contact with turned into hits. Expressed as a .406 Batting Average on Balls in Play, or BABIP, it was the eighth-highest seasonal mark in the previous century of baseball, on a list topped by literally Babe Ruth, back when he was smashing baseballs at wildly unprepared fielders who had been born in the 19th century.

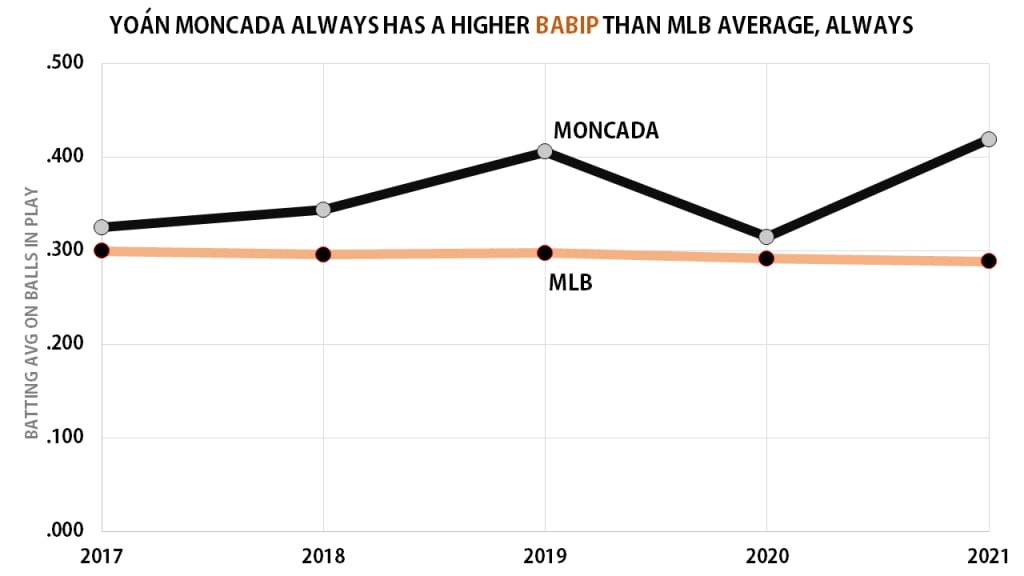

That’s a tough thing to do once, much less multiple times, and in 2020, a season where Moncada suffered from the effects of COVID-19, he didn't repeat it. His .315 BABIP was still higher than the Major League average of .292, but not unreasonably so. It looked “normal,” at least in a year where nothing else was.

That’s because BABIP is generally considered a mix of luck (“Are your batted balls finding gloves, or finding holes?”) and tendencies (“Do you run fast? Are you shifted often? What kind of contact do you make?”), and your yearly number is an often-difficult-to-predict combination of the two. For example, Carlos Correa’s career BABIP is .314, but that’s been as low as .282 (2018) and as high as .352 (2017). It can bounce around a bit.

So even if Moncada is truly a high-BABIP player, well, that 2019 would still look like a fluky year. Except, of course … if it wasn’t.

That’s because this year, entering Tuesday night's games, Moncada has posted a .419 BABIP. That’s the fourth-highest mark in a season in Major League history, which for these purposes, starts with the Live Ball Era in 1920. His 2019 is now the 11th-highest mark. What in the name of Rogers Hornsby is going on here?

“Maybe it’s about short seasons,” you correctly question, noting that Michael Conforto last year and Nick Castellanos this year are represented on that list, for the moment anyway. Perhaps so. Conforto’s .412 mark was clearly a good-luck fluke in a two-month season, since he’d topped .300 only once before, and almost certainly would not have maintained it over a full year. Castellanos is crushing the ball all over the place, so maybe he’s just spraying rockets, but his .410 is nearly 50 points higher than his previous best. He, too, is unlikely to keep this up all year.

Moncada, however, had done this before. He’s been better than the league average in each of his five seasons in Chicago. What he’s doing looks less like a fluke, and more like a skill.

All of which means we’ve somewhat buried The Big Story here. When you look at every player who has ever had at least 1,500 plate appearances in a big league career since 1920 -- we’re talking more than 2,600 careers here -- Moncada’s total BABIP of .369 is second best ever on a list where the other four members of the top five are Hall of Famers. Outside of Hornsby, who last played in 1937, no one has ever done this.

(We’ll pause here and note that baseball is ever so slightly different from when Hornsby played. Obviously. Because he struck out only 7% of the time, 78% of his plate appearances ended with something “in play.” Moncada strikes out four times as much, so only 55% of his plate appearances are “in play.” It’s not exactly the same. Then again, Hornsby never played a night game or played integrated baseball or flew cross-country or faced shortstops like Andrelton Simmons. Let’s acknowledge this, and move on.)

Moncada has taken this one particular thing -- getting hits when the ball does not go over the fence -- and made it into something of an art form. Moreso, he’s doing it at a time when the exact opposite is happening, because the Major League BABIP in 2020 and ‘21 are the two lowest numbers of the 21st century. It’s not just about strikeouts, is the point; when contact is made, hits are less likely to follow. Unless, of course, your name is Yoán Moncada. We’re going to need to figure out how he’s doing this.

Let’s start splitting things up. Moncada is a switch-hitter. Is this a thing from both sides, or just one? Is it about ground balls, or something else? He does have good speed, though more “solid” than “elite.” Is he beating the shift? Is he not being shifted? Does he hit the ball differently than everyone else? Where is he realizing these BABIP gains? There’s so much to look into here. Let’s go on a journey.

The ways you want to hit the ball -- or not

Think about the four generally accepted types of batted balls, and how often they turn into hits in the Majors since 2017.

Ground balls

MLB: 45% of batted balls, .244 BABIP (.511 OPS)

Moncada: 41%, .330 BABIP (.695 OPS)

Line drives

MLB: 25% of batted balls, .613 BABIP (1.572 OPS)

Moncada: 30%, .641 BABIP (1.688 OPS)

Fly balls

MLB: 23% of batted balls, .116 BABIP (1.158 OPS)

Moncada: 24%, .140 BABIP (1.259 OPS)

Popups

MLB: 7% of batted balls, .022 BABIP (.047 OPS)

Moncada: 6%, .000 BABIP (.000 OPS)

Popups are death. Don’t hit popups. They’re basically strikeouts that go in the air. Fly balls are fine if you get them over the fence, but really only if you get them over the fence. Ground balls have their moments. But if you want the good stuff, the outstanding contact that more often than not turns into a hit, and sometimes an extra-base hit? You want line drives. Lots of line drives.

Moncada hits more line drives than average, with somewhat better outcomes on them. He gets much better outcomes on his ground balls than average. There’s nothing interesting about his fly balls or popups. We can ignore them. That’s a good start.

Now, what about how hard he hits the ball ... and how often he does not?

Never hit for weak contact

Moncada strikes out a lot. A lot. If there's one upside to that, it's that you can't strike your way into a batted ball out. We're kidding, but only a little; it'd be harder for teammate Nick Madrigal and his elite contact rate to do this, just because he's got so many more balls in play.

So that helps, but so does this. Over the last five seasons, 361 players have made contact with at least 500 batted balls. Look at the very, very, very bottom of the "weak contact" list, the kind of sub-60 MPH contact that is worth little and gets you little.

1. Victor Robles (10.1%)

----

359. Jed Lowrie (1.6%)

360. Matt Chapman (1.5%)

361. Yoán Moncada (1.4%)

No one, and we mean no one, over the last five years, has hit into that weakest kind of weak contact less than Moncada.

We're on the right track here. Now, how about the fact that he’s a switch-hitter?

The two different Moncadas

Batting righty, career: .381 BABIP

Batting lefty, career: .364 BABIP

Moncada is a much stronger batter overall from the left side for his career, but that’s mostly about the fact that as a lefty, he hits for more power, draws more walks and strikes out less. It’s not about balls landing for hits, because as you can see he’s better at that as a righty. If you’re wondering about the shift, he’s seen it 43% of the time for his career hitting lefty … and just 4% of the time as a righty. (And just once in 2021; he hit a line drive for a single.)

This is where some of Statcast’s expected stats, which show how often a particular batted ball (based on exit velocity and launch angle) becomes a hit can come in handy. Because it doesn’t include horizontal direction or fielder positioning, just quality of contact -- things which obviously affect whether a ball is a hit or not -- it can give us a good baseline to see where he’s finding his hits.

It’s … pretty stark.

Batting righty, career: .317 expected BABIP (.381 actual)

Batting lefty, career: .354 expected BABIP (.364 actual)

As a lefty, Moncada has the third-highest expected mark since 2017, and the No. 1 actual. There’s little difference. You can take that as him doing something special with the way he hits the ball, as quality of contact alone -- excluding luck, excluding fielder positioning -- suggests he should have such a high mark.

But as a righty? Moncada has the 93rd-highest expected mark since 2017 … and is tied for the third-highest actual mark. The gap of 64 points is the largest.

So, as a lefty, he’s hitting the ball in a special way. As a righty, he’s not doing anything terribly special, but he’s getting incredible gains above his expected outcomes on it. It seems clear we’re going to have to stop looking at “Yoán Moncada” as though he’s a single ballplayer. There’s a lefty Moncada, and a righty Moncada. They perform very differently.

The Lefty Moncada

As we noted, when he’s hitting left-handed, he’s doing something particular with the way he hits the ball that makes it more likely to find grass or dirt rather than gloves. Remember: This is entirely about balls “in play,” so it’s not about home runs. It’s not about bunting, either; he’s got two career bunt hits, none since 2019.

It is, primarily, about line drives.

Unsurprisingly, that’s a thing that Lefty Moncada does very, very well. So far this year, 145 lefties have connected with 50 or more batted balls, and Lefty Moncada’s line-drive rate is third-best. In 2019, he was tied for seventh-best of 176 lefties with 100 batted balls. In his White Sox career, dating back to 2017, he’s third-best, and the only two names ahead of him are “elite bat controller Luis Arraez” and “Hall of Fame caliber superstar Freddie Freeman.”

So that’s how you get a BABIP number that is both “expected to be good” and “actually good.” You stroke line drives more than almost anyone. You find the highest-value type of batted ball and … do that.

He's overperforming on ground balls, too, by 47 points since 2017. This is a little about hitting the ball hard; he's just outside the Top 10 in hard-hit rate on ground balls by lefties since '17. It's a lot about being unpredictable. Think about it this way: Since 2017, 234 lefties have hit 100 ground balls. He pulls those grounders the 77th most. He hits them up the middle the 129th most. He goes opposite field the 186th most. It makes him somewhat hard to position; while he's steadily being shifted more and more as a lefty, this is hardly a Joey Gallo situation where a shift is in place nearly every single time.

So far as Lefty Moncada goes, it's simple. Hit more line drives than most anyone else: Check. Hit ground balls harder than most anyone else: Check. Hit those grounders in enough different places so the shift isn't killing you: Check.

Now: What about Righty Moncada?

The Righty Moncada

Meanwhile, Righty Moncada is a little different. His contact is good, not special. His career line-drive rate is 39th, which is fine, but not elite. It’s similar to Dansby Swanson or Yadier Molina, and we’re not writing about their elite BABIP skills. Righty Moncada gets a ton more value out of his liners than most -- a .700 BABIP is outstanding, meaning that 70% of the non-homers land for hits. He gets a lot more of his grounders, too; a .331 BABIP is fifth-best.

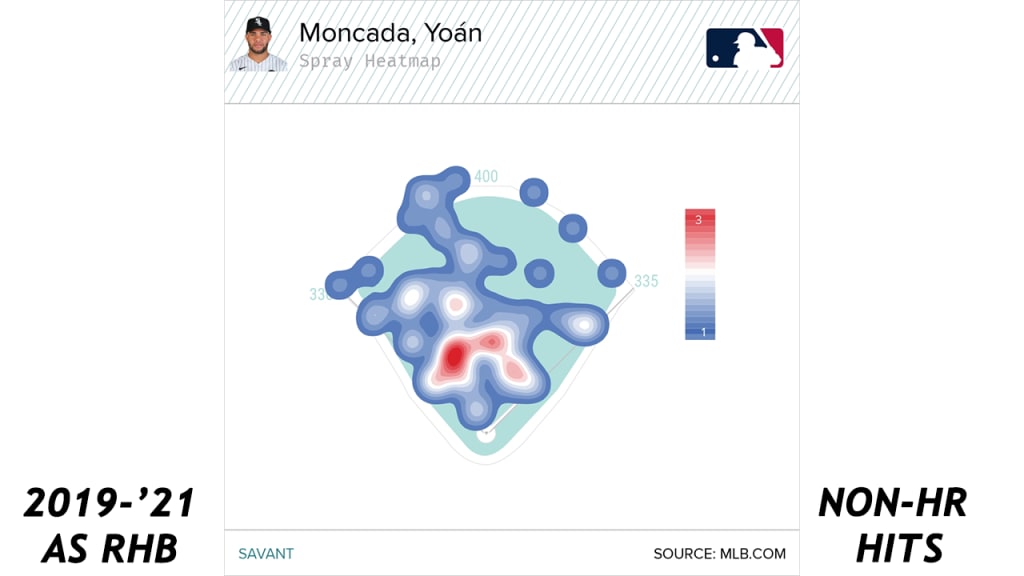

Righty Moncada doesn't hit his ground balls hard; he's actually well below-average there. The same is true for line drives. How, then, is he managing to find all these extra hits? A good place to start would be here, all of his non-homer batted balls as a righty over the last three years, and maybe this tells you why he's almost never, ever shifted against from that side.

That's difficult to defend against, especially in an era where improved defensive positioning is costing batters many, many hits per season. ("Positioning," importantly, not being the same as "shifting.") It's also at least a little fluky, this year, anyway. Moncada has a .531 BABIP as a righty -- that means more than half his non-homer batted balls are becoming hits -- and were he to keep that up, it would easily be the highest mark by a righty batter in the pitch tracking era, back to 2008.

We don't think that's likely to happen. Then again, we didn't really think Moncada would be well into May having outdone the batted ball skill he showed in 2019, either. We didn't think we'd ever have him on an all-time leaderboard right behind Rogers Hornsby. If anyone can keep that kind of magic going, maybe Moncada is the man to do it. After all, he's been doing it.