Pitchers miss bats. Lots of bats. They do it all the time. Last year, including the playoffs, there were nearly 90,000 swings-and-misses in the Majors, because it’s so hard to hit a baseball. You know what it looks like, because you’ve seen it so many times.

Yet all whiffs aren't created equal, are they? It’s one thing to miss a bat by inches, and another thing entirely to miss one by feet -- to fool a batter so badly that it’s not so much that the batter couldn’t get the stick there in time as it is that he was going after a pitch that simply wasn’t there.

Those misses, the ones where the batter’s swing path isn’t in the same Zip code as the pitch, don’t actually count for a strike any more than the ones where the bat misses by molecules. But they might help us learn a little about the pitchers who can do that, too. In a sport where dominance on the mound matters above all else, missing bats by a lot as compared to a little might separate the great from the good, and it might give those pitchers a little more wiggle room in the future should they start to descend from their peak.

It also might just give us some fun stories to share, too.

As we continue our work on bat-tracking metrics being available beginning with the 2024 season – as we did with “swords” in January – we can provide a taste of what’s to come, using 2023 partial-season testing data. In this case: Which pitchers, and pitches, missed bats by the most last year? On which pitches did they do it?

As with everything, a simple-seeming question – how much did the bat miss the ball by? – requires some explanation. For our purposes, we’re defining this as “what was the closest the bat ever came to the ball in 3D space,” regardless of plate position, and also defining the bat as “the top half of the bat,” from the head down to above the handle. That’s because when a hitter chooses to swing, he’s trying to do damage, and that means the barrel, or at the very least the head of the bat. No one’s trying to come close to the ball with the handle, though of course it happens sometimes, and for this look, that’s a miss.

The biggest miss of the year

4.7 feet, by Sam Hentges

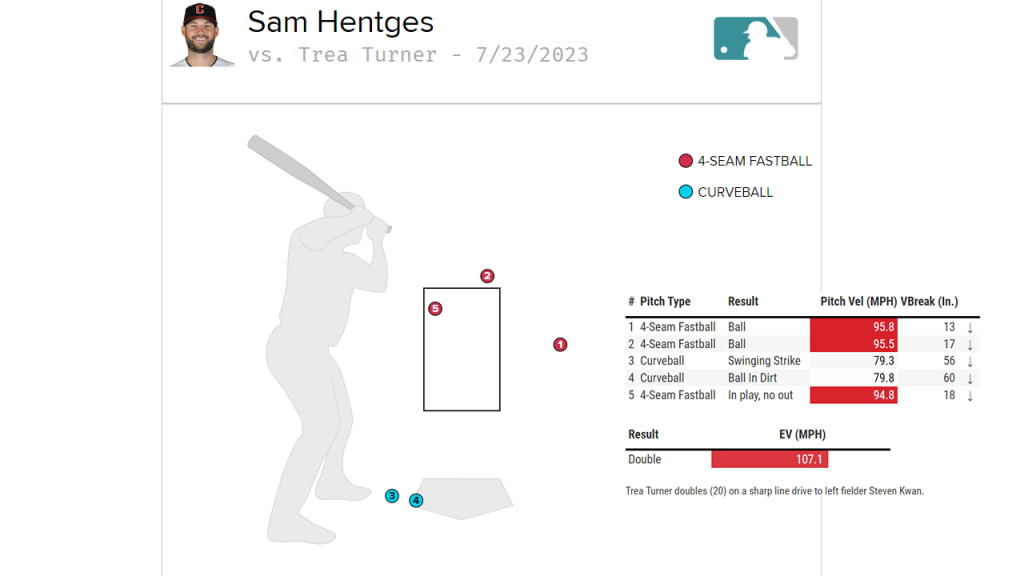

Sam Hentges! Didn’t see that coming, did you? Hentges has certainly become a useful reliever for Cleveland (2.91 ERA over the last two seasons), but he’s not exactly a high-profile arm even in his own bullpen. Yet on July 23 of last year, he fell behind Trea Turner 2-0, then dropped a curveball that made Turner do this:

That may not look like much, does it? Though the home broadcast accurately noted that Turner was “way out in front,” it’s hard to see what really happened from that angle, behind the pitcher.

Instead, let’s move this one over to 3D simulator space to really see how far away Turner’s bat was, because he was actually so far out in front that he'd essentially finished the competitive portion of this swing before the ball even reached the plate. It was the only tracked swing in the test data to miss by at least four feet. It was the largest miss by nearly an entire foot. He missed by nearly 85% of Jose Altuve's height.

So, how does a good-but-hardly-elite reliever like Hentges do that to a two-time All-Star like Turner? It’s all in the setup. Hentges’ first pitch was a 95.8 mph four-seamer, outside. His second pitch was a 95.5 mph four-seamer, high.

Now it’s 2-0 in Turner’s favor, which is a bad spot for a pitcher. In Hentges’ career, when he’s in similar situations (facing a righty batter, behind in the count having thrown at least two balls), he throws a fastball two-thirds of the time, so you can understand why Turner was ready for another 95 mph heater. He might have even been on time for it, too, had he gotten it. He did not.

Instead, he got the curveball that was 16 mph slower and with more than three feet of extra downward movement. For all of the new technology and thinking we have, sometimes “change speeds and eye levels,” as pitchers have been taught for 500 years, still plays. Turner didn’t come close. “Baseball is a game of inches,” they say, and if that’s true, then in this case, we’re talking about 56 inches by which Turner’s bat missed the ball.

But all wasn’t lost. Turner got the last laugh, which is ultimately all that matters. After Hentges tried to double up on the curveball low in the same spot – Turner held off this time to go up 3-1 in the count – he caught too much of the plate with another 95 mph fastball. This one turned into a double to left. Turner wins.

The biggest miss of the year (fastball division)

2.1 feet, by Lucas Giolito

As you might expect, most of the biggest misses come from breaking balls or offspeed pitches, because only three of the first 1,250-plus misses came on four-seamers or sinkers. But eventually, a fastball was going to pop up, and it came from Lucas Giolito – to, of all people, a man who just a week earlier had been his Angels teammate: Matt Thaiss.

Unlike with the Turner example, you can see this one pretty easily on the video. Thaiss clearly didn’t expect 95 mph heat, and he was totally unprepared to swing. When he did so, it was already too late.

The 3D view shows just how uncertain Thaiss was. Perhaps that's because the previous two pitches had each been changeups, high in the zone, for strikes, at a velocity 15 mph below the fastball. With the bat slowed down, Giolito chose to speed up. If a swing path could scream indecisiveness, this would be it.

But as with Turner, Thaiss ended up getting his revenge. The next time up, Giolito went slow again, throwing a changeup on the first pitch. This time, Thaiss was on time, and it landed 376 feet away in the right-field seats.

This was one of just three four-seamers in the entire data set to miss a bat by at least 1.5 feet, for what it’s worth, because it’s very hard to miss a fastball by that much. The other two (Luke Weaver to Andrew McCutchen, and Michael Kopech to Gabriel Arias) looked pretty much the same way.

The biggest miss of the year (Luis Arraez division)

8 inches, by Justin Steele

Baseball’s foremost contact artist is nearly impossible to strike out; his 5.5% strikeout rate last year wasn’t just baseball’s lowest, it was barely more than half of the second lowest, which was Jeff McNeil’s 10%. As impressive as that sounds, there’s more to it, because remember: Pitchers strike out far, far more batters than they did decades ago. Arraez whiffing 5.5% of the time in the context of 2023 baseball is a lot more incredible than, say, Phil Rizzuto striking out 5.3% of the time in 1950.

To put that into context: If you go back over the last half-century, to the start of the DH era in 1973, only two hitters have been harder to strike out compared to the league strikeout rate of their day – and one was Tony Gwynn.

But as elite as Arraez is as making contact, even he’s not perfect. When he misses, and he rarely does, it’s by almost nothing; his average miss distance of 1.8 inches last year was the smallest of more than 400 hitters who had at least 25 missed swings. (The most? José Barrero, Nelson Cruz, and Elehuris Montero all tied at 5.5 inches, just ahead of Nolan Arenado and Nick Castellanos.)

So: Is it even possible to make him look bad? When we ordered every swing from largest miss to lowest, it took six thousand, six hundred and fifty-nine swings to finally get to Arraez’s name on the list, meaning that it’s possible, but it sure isn’t easy. It took Justin Steele, who finished fifth in the 2023 NL Cy Young voting, and a nasty left-on-left slider to do it.

We don’t even really need to get into 3D space to show this one, because the video gets the point across well enough, but we’ll do it anyway, just to point out: This miss is a perfectly normal baseball miss, which doesn’t really even stand out for most batters – yet for Arraez, it’s his worst mistake in the entire data.

It was one of just two Arraez misses in the top 12,000 or so misses. It’s true that he may not rate highly in exit velocity, and he won’t rate well in swing speed, either. It doesn’t mean that we can’t highlight how truly elite at the things he’s great at, either.

Largest average bat miss

Fernando Cruz, RHP, Reds (6.6 inches)

If you’re surprised by this one, so are we, because Cruz, 34 in March, has had a wild baseball ride. Drafted as an infielder by the Royals way back in 2007, Cruz became a pitcher in 2011, then (aside from some time in the Cubs system in 2015) spent the next decade either in Mexico, independent ball, or not pitching at all. He finally made his Major League debut at 32 with the Reds in 2022, and has struck out 119 in 80 2/3 innings since.

It’s not the profile of a pitcher who misses bats more than anyone else, at least among those with 50 swinging strikes – and yet there he is, with an average miss distance of 6.6 inches.

Biggest average miss distance

- 6.6 inches // Cruz, Reds

- 5.8 inches // Yency Almonte, Dodgers

- 5.8 inches // José Soriano, Angels

- 5.6 inches // Robert Stephenson, Pirates/Rays

- 5.6 inches // Alex Lange, Tigers

- 5.5 inches // Eury Perez, Marlins

- Minimum 50 swinging strikes

If there’s something that list should give away, it’s this: If you’re going to lead a list of average miss distance, it sure helps to not primarily throw a four-seamer or sinker. Cruz threw his splitter more than any other pitch; Almonte threw his sweeper 50% of the time; Soriano and Lange are curveballers. Stephenson’s cutter is essentially just a slider thrown harder, once he was traded to Tampa Bay.

So it’s that, largely, but it also helps when that splitter is absolutely filthy. Last year, 53 pitchers got at least 25 swings on their splitters, and only one, Baltimore’s elite relief ace Felix Bautista, got a higher whiff rate than Cruz did. Cardinals star Paul Goldschmidt found out when he missed this one by more than two feet.

The splitter sure seems like it’s going to be the “it pitch” of 2024, and Cruz has shown he’s got a fantastic one.

Does Ohtani the hitter miss less than Ohtani the pitcher does?

This is always the question, right? Is Ohtani a better hitter, or is he a better pitcher? We won’t answer that today, but we did find it incredibly entertaining that if you look at the comparison ...

- As a pitcher: 3.7 inch average miss distance

- As a hitter: 3.5 inch average miss distance

… you won’t really find a difference.

In the test data, Ohtani the hitter missed by more than 1.5 feet five times … and Ohtani the pitcher made hitters miss by more than 1.5 feet four times. Pitcher Ohtani’s biggest miss created (more than 22 inches) was nasty enough that not only did Willi Castro not come close, but the catcher couldn’t corral it either, leading to a wild pitch.

The highest miss above the bat

1.4 feet, by Nick Pivetta

What if we look directionally?

As you’d expect, most of the biggest misses above the bat are fastballs, because who manages to miss a curveball by swinging under it? Ninety-nine of the top 100 biggest misses above the bat were a type of fastball, and the one outlier, a slider, was thrown at 88 mph, which is faster than some fastballs anyway. The average fastball miss is nearly two inches above the bat, while the average curveball miss is more like 4.5 inches under the bat – all as you’d expect.

Pivetta got just a little more than two inches above the bat here, because this ball was nowhere near the strike zone – it reached the plate at just over five feet off the ground – and we don’t need to tell you that CJ Abrams probably shouldn’t have gone after this one, since his reaction, and belatedly doomed attempt to hold up, tells you that all by itself.

To Pivetta’s credit, he’s been working on elevating that four-seamer steadily over the years. He probably never expected a swing on this one, though.

Because we know what the next question is, let's go from up to down.

The biggest miss under the bat

2.5 feet, by Mitch White

You kind of knew that this one was going to have to look funny, and …

… well, yes, it does.

This was the first pitch of the plate appearance, and White had never faced Jung before. He never threw a curveball quite like this at any other point in the season, either, because you don't often get a swing on a pitch that bounces that far in front of the plate. This was almost certainly just a bad mistake that Jung bailed White out of. They can't all have strategy or meaning, really. Sometimes the answer is: baseball.

Thanks to MLB.com colleagues including but not limited to Clay Nunnally, Dana Bennett, Tom Tango, and Graham Goldbeck for their assistance.