The Mets have traded for Marcus Stroman, and whether or not that's a good move depends very much on your perception of the two prospects sent to Toronto as well as how likely you think a Mets run in 2020 might be. But most importantly, it depends on what happens next. The Mets may or may not trade Noah Syndergaard, or Todd Frazier, or Jason Vargas, or Zack Wheeler, or Edwin Díaz. Maybe they'll even flip Stroman.

But it's the potential of trading Díaz that might be the most interesting, given his position as the centerpiece of the currently-regrettable-looking trade that brought Robinson Canó to town last winter at the cost of prospects outfielder Jarred Kelenic (ranked No. 24 on Pipeline's updated top 100) and right-hander Justin Dunn (No. 77). Despite his 4.95 ERA and a few highly visible meltdowns, there's seemingly a daily stream of rumors connecting Diaz to any contender with a desperate need for relief pitching, which is to say every single contender.

For the Mets to turn around and trade Díaz, they'd have to be okay with the PR backlash that would come from moving him just months after acquiring him. They'd have to figure out how to replace him next year and in the years to come. And most importantly, they'd need interested teams to look past that 4.95 ERA.

The good news is: Most teams aren't just going to look at ERA. Plenty of clubs would prefer Díaz to, say, Shane Greene, despite Greene's pretty-but-unsustainable 1.22 ERA. Even if Díaz isn't as good as he was in 2018 -- he's not -- it's not the same thing as not being able to help. He can.

The bad news? You don't get to a 4.95 by accident, not completely. Here's how Díaz has come to that number, and what might make teams still believe he's got the capability to be an elite reliever worth trading for.

1) Just ignore the ERA.

Díaz has allowed 22 earned runs this year. More than half of them, 13, came in three awful outings, disastrous games against the Phillies (June 27 and July 5) and Dodgers (May 29). You can't simply pretend those games didn't happen; they did, and they were bad. But because relievers don't throw many innings, a bad game or three can ruin their ERA for months. In Díaz's other 39 innings over 41 games, his ERA is: 2.08.

Every pitcher, obviously, looks better if you strip away their three worst games. Kenley Jansen's ERA, for example, is 3.67; absent his three worst games, it'd be 1.84. As noted, this isn't about "pretend bad things didn't happen" so much as it is a reminder that ERA doesn't do a great job of telling you how well a reliever is pitching.

That said ...

2) The strikeouts are down, but they're still good.

Last year, Díaz whiffed 44.3% of the batters he faced, second-best behind only Josh Hader (46.7%) of the 396 pitchers who threw 40 innings. This year, that number is down to 34.7%, which is of course a big drop, because he's converted 10% of batters from strikeout victims into doing something else. That said, 34.7% is still very good. It's 18th-best of 281 pitchers who have thrown 40 innings; it's better than elite relievers like Ryan Pressly, Adam Ottavino, or Aroldis Chapman.

So that's both bad -- it's worse than last year! -- and good -- it's a strong number! -- at the same time. But why? Díaz mainly throws two pitches, a four-seam fastball and a slider. We'll have to look at both.

If we start with the fastball...

3) The heater is still there.

Last year, Díaz got a swing-and-miss on 30.8% of the fastballs hitters put a swing on, 10th-best among 214 pitchers who got at least 200 swings on their fastballs. This year, that number is up to 33.9%, sixth-best.

The fastball hasn't lost any velocity (97.3 MPH last year, 97.2 MPH) this year. He's actually allowed a lower average distance on fly balls / line drives (284 feet last year, 271 feet this year) from fastballs, and a nearly unchanged exit velocity on those balls. While it's true that his four-seamer is allowing a much higher slugging percentage (.250 last year, .417 this year), his expected slugging, based on exit velocity and launch angle, shows a pitcher who probably over-performed last year (.294 expected) and is finding unfortunate outcomes this year (.313). We'll get back to that concept in a minute.

All of these numbers, anyway, are well below the 2019 Major League average of .483 slugging allowed on four-seamers.

So that's good; the four-seamer isn't broken. But we do have to talk about the slider...

4) The slider is missing something.

Díaz's slider has long been one of baseball's truly nasty pitches, and we still see that sometimes.

You don't have to go much further than average and strikeout rate to see the problem here.

Slider average against, 2016-19 -- .141, .144, .129, .321

Slider strikeout rate, 2016-19 -- 55.6%, 44.6%, 56.4%, 28.3%

(Note: slider strikeout rate means "percentage of PA ending on that pitch resulted in a strikeout")

It's not velocity; his 89.0 MPH is nearly identical to last year's 89.1 MPH. It's not spin; his RPM number is all but unchanged from last last year. His pitch movement profile is unchanged. Last year, he got 6.4 feet of extension on the pitch; this year, it's 6.5 feet. From 2016 through 2018, there was a good argument that Díaz had one of the best sliders in the game. This year? It's been one of the worst.

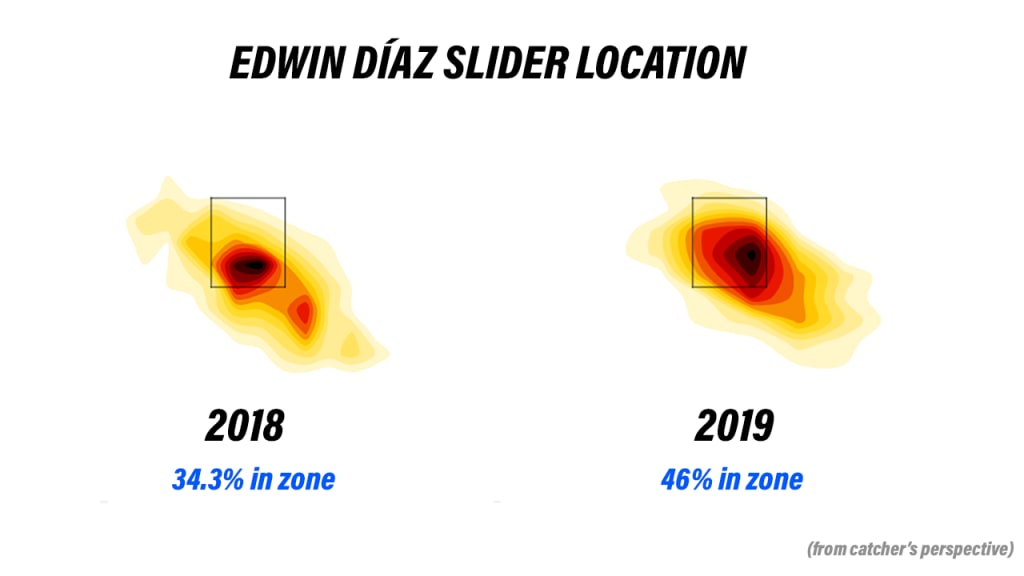

This is pretty clearly one of his largest issues, but the reason behind it isn't so clear. There's always the difficult-to-quantify possibility of tipping or lack of deception, but the largest issue here seems to be one of location. At its best, his slider is one that hitters can't prevent themselves from chasing. In 2017-'18, Díaz's slider was in the zone about one-third of the time. This year, that's up to 46% of the time.

It's a lot easier to see in heat map form, isn't it? Meatballs. So many meatballs.

Fewer swing-and-misses. More damage done, in terms of more distance on fly balls and liners (282 feet last year, 296 this year), more exit velocity allowed on those flies and liners (93.1 MPH last year, 94.5 MPH this year), and, obviously, in outcomes (.234 slugging on all sliders last year, .571 this year).

We can't say with certainty why that's happening, why Díaz can't command the slider as well, but it is happening, and, probably, it's having some sort of secondary effect on hitters being prepared to face his fastball.

(Pure speculation alert: No catcher in baseball has been weaker at framing the low pitch, marked as 'Zone 18' in this link, as Wilson Ramos, and we know Ramos has had difficulty working with Syndergaard. But last year in Seattle, then-Mariner catcher Mike Zunino was one of the five best at it. Might Ramos's struggles be causing Díaz to lose confidence in burying his slider? It's far from clear, but it's at least plausible.)

So, when you take a truly elite pitch, one of only two a pitcher has, and you make it much worse, you end up with ....

5) He's been getting hit a lot harder.

A lot harder. Last year, Díaz's hard-hit rate (that's percentage of batted balls hit at 95 MPH of exit velocity or higher) was 35.3%, about league-average. This year, it's 44.6%, one of the highest marks in the game. This isn't just about how we're on track to shatter every homer record in history, because that's been more about how far the ball flies. Díaz, without his usual slider, has been getting hit hard.

That's on him, no one else, but even with that being said ...

6) He's giving up a lot more damage than he's earned.

Díaz was otherworldly last year. He's striking out fewer this year, though still a lot, and giving up a lot more hard contact. You'd expect him to be worse; he is worse. But there's something else happening here, too.

Díaz has allowed a Batting Average on Balls In Play of .398, which isn't just the highest of any qualified reliever this year, it's the sixth-highest in the entire history of baseball. Even if you don't know what BABIP does -- it excludes strikeouts and home runs to just look at outcomes on balls the defense has a shot at -- you know that a ranking like that tells you something is fishy here. When Díaz allows a non-homer batted ball, it turns into a hit at a higher rate than nearly every pitcher ever.

Now, as we just pointed out, some of that is on him, for allowing the hard contact. But we can use some Statcast metrics to dig a little deeper here. Díaz's expected BABIP -- that is, what you might have expected to see based on his combinations of exit velocity and launch angle -- is .344. Of the 382 pitchers who have allowed 75 non-homer balls in play, only eight have a larger negative gap between expected and actual, which aligns with what we know about the below-average Mets defense -- especially since one of the eight is Díaz's New York teammate Jeurys Familia.

On just grounders, it's even worse. Díaz has allowed a .514 average on grounders, the worst in baseball, yet he's allowed an expected .344 on grounders. The difference is baseball's third largest.

Every pitcher has moments like the one shown in this video, obviously. Díaz just seems to be finding them a little more this year.

7) All told, he's still been an above-average pitcher.

The 4.95 ERA, obviously, is difficult to look past, and there's no argument to suggest that he's been as good as he was for Seattle in 2018. He's not. If we look at a metric like Expected Weighted On-Base Average, which attempts to strip out the effects of ballpark and defense and just looks at quality of contact and amount of contact, Díaz was, last year, the third-best pitcher of the 436 who faced at least 150 batters.

This year, that's 44th of 330, which is still strong; it's 86th percentile. If not quite Hader or Kirby Yates, it's still similar to Ottavino or Felipe Vázquez.

You can see the appeal here now. If some team -- Mets or otherwise -- can help Díaz fix the location of his slider, then that's a big step. (If it's as simple as a better catcher, wonderful; it might be more complicated.) If some team can put a better defense behind him in order to turn more of those batted balls into outs, even better.

Those are some big "ifs," obviously. But Díaz is still only 25 years old, and there's no noticeable loss of velocity or movement or spin on his pitches from last season. There's some real problems with his slider, though nothing we can see that can't be resolved. There's been some bad defense and unfortunate outcomes. These are things that seem like they can be fixed, one way or another. You can see why contenders are so interested in a man with a 4.95 ERA. If they can buy low, they reason, they might just find a pitcher who resembles the one so valuable the Mets gave up two elite prospects and took on the Canó deal for him.