As though baseball in 2020 hasn't gone through enough changes, here's another one, and it's more meaningful than it might seem. Major League Baseball and the Players Association have agreed that for the first three rounds of the 2020 postseason, there will be no days off within a series. Once a series starts, there's baseball each day until it ends. This is going to be so important.

That's because in the Wild Card round, the best-of-three series will take place entirely at the home stadium of the higher-ranked team. The Division Series (best-of-five) and Championship Series (best-of-seven) will take place entirely within one of the bubbled areas in California or Texas. (The best-of-seven World Series will still have days off after Games 2 and 5, as usual.)

The reasoning here is simple: No travel means no travel days. You won't have the Dodgers and Braves playing two games in Los Angeles and then needing time to fly cross-country to Atlanta, as happened in the 2018 NLDS. Everyone stays in the same place. There's less need for days off, and so there won't be any.

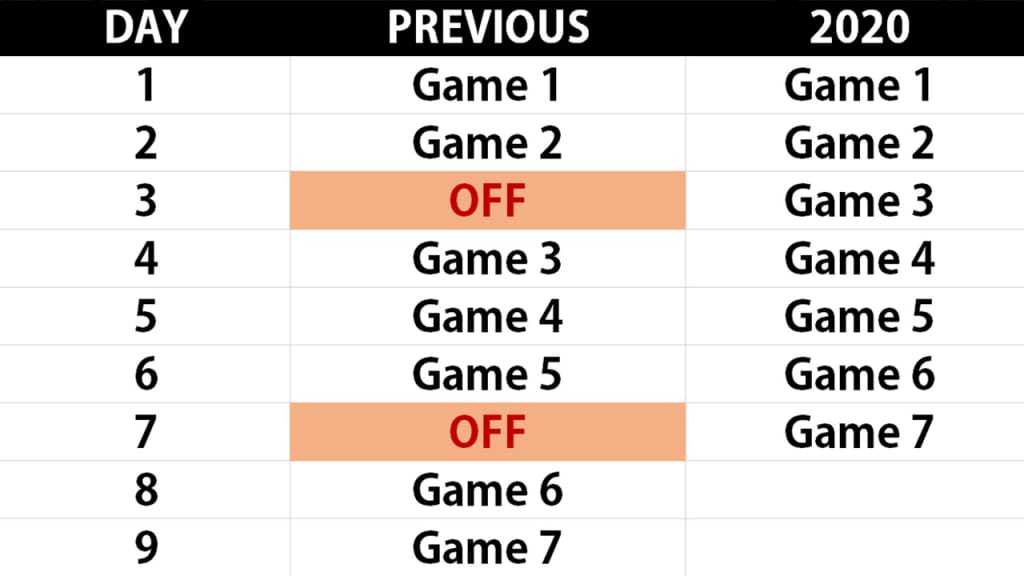

That doesn't leave you any time to breathe. More importantly, it doesn't leave you any time to rest. Just look at what a 2020 seven-game ALCS or NLCS might look like, compared to what usually happens.

Those big red flashing "OFF" days might as well read: "recharge your ace reliever." No longer.

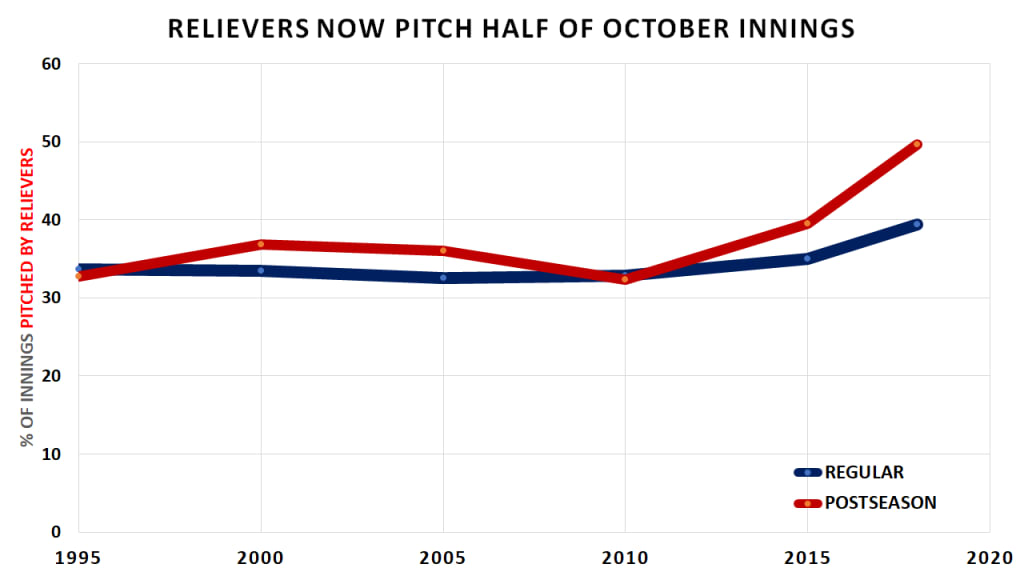

That might seem innocuous, but it's going to have some pretty major implications for pitching strategy. If it feels like October baseball is from a different planet than regular-season baseball, that's because it is, as it's been taken over by endless streams of relievers even more than the regular season has. If we may quote ourselves, from one year ago:

In 2010, for example, [relief pitchers'] 32.9 percent regular-season share of innings and their 32.3 percent postseason share of innings was essentially equal.

It began to take off from there, and now ...

... we have reached a 50/50 split, at least in October. In 2018, relievers pitched 39.4 percent of regular-season innings. In the postseason, they pitched 49.7 percent of innings.

More importantly, it was considerably higher usage than we saw in the regular season. That reversed itself slightly in 2019, mostly because the October Nationals tried to build the entire plane out of starters; it clearly seemed to be more of a fluke from a team with enormous bullpen concerns rather than a trend.

As we continued to detail last year, October baseball gets very different. Fastballs get faster, strikeouts go up and offense goes down. It is not difficult to explain why: There are better teams using better pitchers as often as they can. (In 2019, for example: hitters had a .758 OPS in the regular season, and a .700 OPS in the playoffs. They struck out 23% of the time in the regular season, and 26.1% of the time in the postseason. This happens like this every single year. It's why the myth that "small ball" works better in October is just that: A myth.)

Put another way: In the 2018 NLCS, the Brewers used Corey Knebel six times in seven games, but over nine days. He was spectacular, striking out 10 and allowing just one run. (He also missed the entirety of 2019 with Tommy John surgery. Make of that what you will.) He managed to do that while never pitching three days in a row, because he pitched in the first two games, got a day off for the travel day, pitched in Games 3 and 4, got two days off for Game 5 and another travel day, and pitched again in Games 6 and 7.

Knebel, or someone like him, almost certainly cannot pitch six times in seven days under the new format. What that would have meant for Milwaukee manager Craig Counsell is a different choice; either pitch a lesser reliever in those spots (which probably makes strikeouts go down) or push a starter deeper into games than he would have liked (which also probably makes strikeouts go down).

It's not just about relievers, either. Think about how heavily teams with top-heavy rotations have been able to ride those horses to the World Series in recent years. While the regular season is often about depth, the postseason has been about stars. Look at last year's Nationals, once more, and their "big three" of Max Scherzer, Stephen Strasburg and Patrick Corbin.

That trio started over 57% of Washington's regular-season games and threw 40% of all regular-season innings, and it would have been even higher if Scherzer hadn't missed a few starts with a back strain.

In the playoffs? Those three made 76% of all Washington starts ... and threw nearly 59% of all Nationals October innings. It's a much higher share of pitches going to a much higher caliber of pitcher.

Now: Maybe you like that! Maybe you like that a top-heavy team like Washington can ride a few elite stars to glory. Or maybe you don't! Maybe you prefer that a team has to rely more on its fourth and fifth starters to make progress, more like it has to in the regular season. (The five primary non-"Big Three" Nationals starters, mostly Aníbal Sánchez but also Joe Ross, Jeremy Hellickson, Erick Fedde and Austin Voth, combined for a 4.04 ERA in their regular-season starts. That has to count for something.)

It's an aesthetic choice, in many ways. If you want the playoffs to resemble something like regular-season baseball, which October baseball rarely does, you might enjoy this. (And if you don't, it might only be a one-year thing, if October 2021 doesn't require a bubble.)

So: Who benefits from this? Who doesn't? It's difficult to say, and it's not exactly the same for a five-game series as it is for a seven-gamer, but let's try to play this out.

1) It's good for teams with more than three solid starters.

We should caveat the obvious here, that neither season-to-date stats nor future projections tell us a ton about what a pitcher will be like on one or two particular days in October. For example, take the Braves, who have obvious season-long rotation problems. If you're looking at season-to-date, then Max Fried (1.98 ERA) has been outstanding, but he's at least a little of a question mark until he successfully returns from a back injury. If you're looking at projections, then Cole Hamels probably fares reasonably well due to his long track record of success, yet he's hasn't thrown a Major League pitch in nearly a year. (He's expected to make his Braves debut Wednesday night.)

You get the idea. We'll do the best we can. Right now, there are nine teams with at least four starters who have made at least six starts with an ERA+ of 100 (average) or better. We can knock out the Rockies, Royals and Mariners, who are each unlikely to make the playoffs.

Here are the remaining six:

5 -- Indians, Dodgers

4 -- Twins, Marlins, Reds, Cardinals

You are shocked to find that Cleveland and Los Angeles have a lot of good pitchers.

Still, even this look is open to interpretation. All due respect to Miami's Daniel Castano and his 3.32 ERA/137 ERA+, but a well-below-average strikeout rate gives him a 5.73 FIP and a 6.10 Expected ERA, which hardly bodes well.

Besides, what's most notable are the teams not represented here. How many Yankees starters do you trust, aside from Gerrit Cole? What do the Astros have if Justin Verlander isn't back, and even if he is? The Rays should have a great rotation, but Charlie Morton and Tyler Glasnow haven't posted results living up their talent -- yet, anyway.

2) It's good for teams with the most good pitchers.

We repeated that, this time with any pitcher who has thrown at least 15 innings. That got us seven teams with at least nine and an ERA+ of 100 or more, all likely to make the playoffs, and of course teams with lots of good pitchers are likely to succeed.

13 -- Dodgers

10 -- Twins

9 -- Rays, Cardinals, Yankees, White Sox, Indians (we removed the traded Mike Clevinger)

That's a great way to view the depth of the Dodgers, who can start Dustin May or Tony Gonsolin as fourth and fifth starters, if they chose to do so.

It will, like everything else this year, be different. You can see the argument that this might have been better off figured out before the Trade Deadline, so that teams like the Braves or Yankees might have tried harder to get an extra good-not-great starter they didn't think they'd have needed two weeks ago. Whether you like this or not might depend on how it benefits your team, or doesn't.

Either way, at the end of October, it seems likely we'll look back and see that this was the postseason where teams had to use most of their pitching staff, not just the top part of it. That sounds a whole lot more like the regular season to us.