Name: John "Famous" Donaldson

Years: It's hard to completely pin down, but research shows Donaldson may have played in an amazing 42 seasons from 1908-1949. Records also have him striking out 18 semi-pro batters as early as 13 years old, and pitching three scoreless innings in an amateur league at the age of 58.

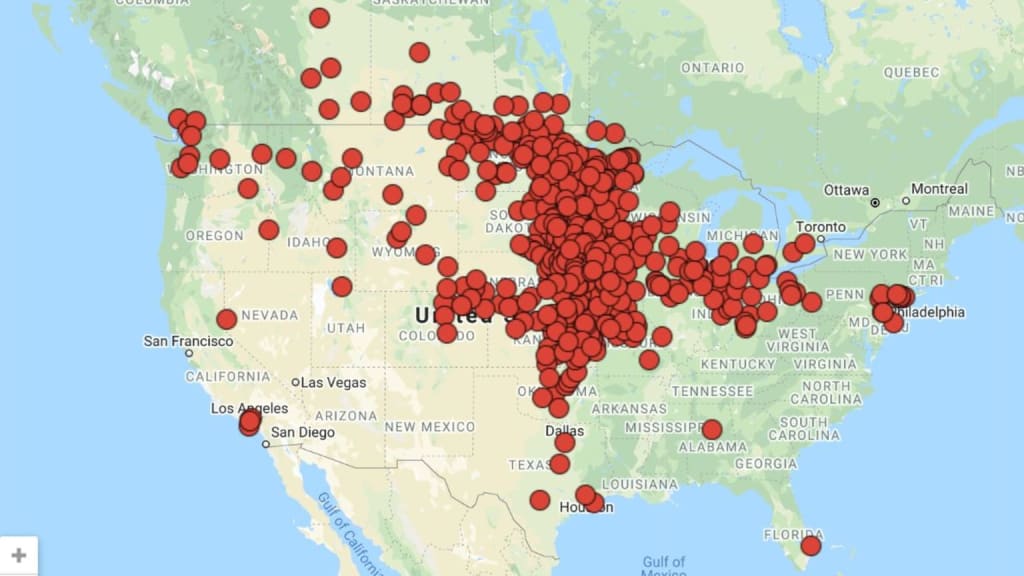

Bio: Born in Glasgow, Mo., in 1891, Donaldson started his baseball career more than a decade before the Negro National League was created in 1920 (one reason why it's difficult to keep track of many of his stats). So, like many Black baseball players pre-Negro Leagues, the lanky left-hander spent much of his career barnstorming all over the country. And because he was so good, he probably was asked to play in more places than just about anyone. Seriously, look at this map. It's been totaled at more than 700 cities.

He took the mound for 25 different clubs, including the incredibly diverse All-Nations Team, the Tennessee Rats, the Missouri Hannaca Blues, the Indianapolis ABCs and a team called the John Donaldson All-Stars. Donaldson did play for the Kansas City Monarchs part-time for two seasons -- pitching and batting cleanup. It's said he may have even come up with the name "Monarchs." But because he was such a draw, "Famous" Donaldson (people even began thinking "Famous" was his real first name), could make much more money traveling to various exhibitions throughout the year. Posters and promoters warned of his arrival:

"He threw as fast as a cannonball could shoot it."

"He made the pill do everything but turn around and come back again, and there were many in the stands who claim that he could do that also."

Buck O'Neill said Donaldson threw a slider 20 years before anybody else did and "showed Satchel Paige the way." Grover Cleveland Alexander called the hurler the greatest he's seen in organized baseball. New York Giants manager John McGraw tried to give Donaldson $10,000 to change his name, move to Cuba and get around MLB's segregation law (Donaldson refused to renounce who he was).

After a long playing career, Donaldson became MLB's first Black scout with the White Sox -- bringing the team young Negro League stars like Willie Mays, Hank Aaron and Ernie Banks (the Sox declined signing any of them). He did get star first baseman Bob Boyd and infielder Sam Hairston signed by Chicago.

Donaldson passed away in 1970 at the age of 79. He's been named on the all-time greatest Negro Leaguers list for an unprecedented 10 consecutive decades and is one of just three names on the 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Black First Team still not in Cooperstown.

Fun stat: Just one? How about four: 413 wins, 5,091 strikeouts, 14 no-hitters and two perfect games. These, and other ridiculous stats, have all been verified by Negro Leagues historian Pete Gorton -- who's dedicated his life to resurrecting Donaldson's career through thousands of newspaper articles. As Gorton told me, "He was dominating a lot of farmers, let's face it. But you have to remember, this is what segregation was. Segregation was push 'em out and get 'em out as far away as possible, and that meant some strange and out-of-the-way places where there weren't Major Leaguers."

Donaldson faced who he was allowed to face, and nobody was better.

Best moment: Playing for the All-Nations team in 1915, Donaldson put up an unreal stretch of 30 consecutive no-hit innings -- making newspapers and MLB owners question why there was a color line at all.

Beyond the numbers: Sure, Donaldson amassed some outrageous numbers over his four-decade career, but his legacy should mean even more to Hall of Fame voters: his trailblazing greatness through mostly white towns, his celebrity status during times of Jim Crow and the Ku Klux Klan. The problem is, he did all of these things so early on -- playing for so many different teams, in so many different leagues, in so many different places, that it's been hard for researchers or analysts to see his true impact. Fortunately, we have Gorton to tell his tale.

"He's the first Black superstar. That's the important part of who he is. He is proof that it is possible for a Black person to be famous. In his time period, that was not possible. Without Donaldson, you don't have Satchel Paige. Without Satchel Paige, you don't have Jackie Robinson. There's pictures and photographs of [Donaldson] being the only Black person. That showed that integration was possible, and not only is integration possible, but success with it is possible."