“For me, this is as good as I can remember him,” said Dodgers infielder Trea Turner last weekend about Max Scherzer, and Turner should know better than anyone. After all, they each joined the Nationals in 2015 -- Scherzer was the starting pitcher in the first game Turner ever started -- and spent parts of seven seasons as Washington teammates before being traded together to the Dodgers in July.

Scherzer had five straight Top-5 Cy Young finishes in front of Turner (winning twice, in 2016 and ‘17), and he’s been arguably the best pitcher in baseball since the pair arrived in D.C. back in 2015. But this -- according to Turner -- is the best he’s ever seen a pitcher already assured of first-ballot induction in Cooperstown? Talk about high praise.

If Turner is just talking about results, it’s not hard to see what he’s referring to. Scherzer has made nine starts for the Dodgers, with the team winning all nine as he’s allowed all of five earned runs. He’s struck out 79 and walked a mere seven; over his last five starts, he’s allowed a single run, and that was unearned. It is almost impossible to pitch better than this, and, in the history of the Dodgers, almost no starter ever has over a nine-start span.

It’s not at all too soon to get into “best Trade Deadline pickup ever?” discussions, really, but as impressive as all that is -- and it is -- those are results. That doesn’t explain how a pitcher who was already succeeding at an elite level managed to kick it up a notch, just after his 37th birthday. What’s different from his time with Washington? How, exactly, is he managing this? Let’s dig into some potential reasons.

Theory one: Maybe the pennant race has amped him up.

This has to be the first place your mind goes, right? After years of good times in Washington, the 2021 Nationals weren’t expected to finish highly in the NL East and have been below .500 since early July. Meanwhile, the Dodgers are engaged in what looks like it might be an all-time great division race with the Giants.

But generally you’d think you’d see that in velocity, and nothing’s changed there. His four-seamer averaged 94.4 mph in May and June, and 94.6 mph in July ... which is exactly where it’s remained as a Dodger.

Nor is he suddenly experiencing a massive improvement in strikeouts. From 2017-20, Scherzer whiffed 34% of the batters he faced. With Washington in 2021, he was at 34% again. As a Dodger, that’s gone up to 36%, which is certainly a little better, but not massively different from his time with the Nationals.

“I feel like that's my best strength, to go out there and compete with some intensity,” Scherzer said after beating the Reds on Saturday, but then again, that’s been his reputation for his entire career.

It’s certainly possible that being in a pennant race has stirred the juices in ways that aren’t showing up in velocity or strikeouts, but so far as those go, it’s not really this.

Theory two: He’s getting lucky.

In no way is this meant to diminish his achievements, it’s just that it’s basically impossible to allow only five earned runs in nine games without some good fortune going your way -- or bad fortune not going against you, if you prefer -- and this is the other obvious thing people would think of.

It’s true in the sense that his 0.78 ERA is a bit more shiny than his 1.35 FIP or 1.97 xERA -- these being variously advanced ERA estimators -- and he is indeed outperforming his expected outcomes by twice as much as he was with the Nationals.

But this falls apart somewhat under investigation, too, because even though his ERA is better than what the underlying numbers might have suggested it should be with the Dodgers ... the underlying numbers themselves are better than they were with Washington. He's better than he should be, but also better than he was.

Scherzer was outperforming to some extent with Washington, too, and he has gotten better with the Dodgers, cutting his walk rate in half and allowing a HR/9 (0.31) five times less than what he had with the Nats (1.46). There’s probably a small amount of good fortune in that, since he’s been one of the most homer-prone pitchers in the bigs for years, and he simply won't suppress homers like that forever -- especially with a start in Coors Field looming Thursday.

It might be better to say “so many things could have gone wrong, and nothing has gone wrong,” more than “good luck is the cause here,” because it’s not. So instead we turn to …

Theory three: He’s not limiting contact; he’s limiting danger.

Now we’re onto something, because this is where all that run prevention success is coming from. It’s not that he’s gaining more strikeouts, not really; it's that when he’s not striking people out, he’s doing a much better job of limiting walks and dangerous contact.

With the Nationals, Scherzer had a 6.5% walk rate. With the Dodgers, it’s 3.2%.

With the Nationals, Scherzer had an 11.4% barrel rate. With the Dodgers, it’s 3.1%.

(A barrel is the perfect combination of exit velocity and launch angle, which we share here rather than slugging percentage or something that could be affected by fielding or ballpark to point out he was allowing nearly four times as much loud contact with the Nationals as he is with Los Angeles.)

This is the correct theory, more than some sudden strikeout dominance. Scherzer strikes out approximately one-third of the hitters he faces, and that hasn’t changed. But in the other two-thirds of the time, he’s limiting walks and the most damaging contact better than ever, and that is new.

But: Why? How?

Theory four: He’s mixing his pitches better.

Something must have changed, and this is it. As good as he was and has been with Washington, he can’t have done everything the same since the trade.

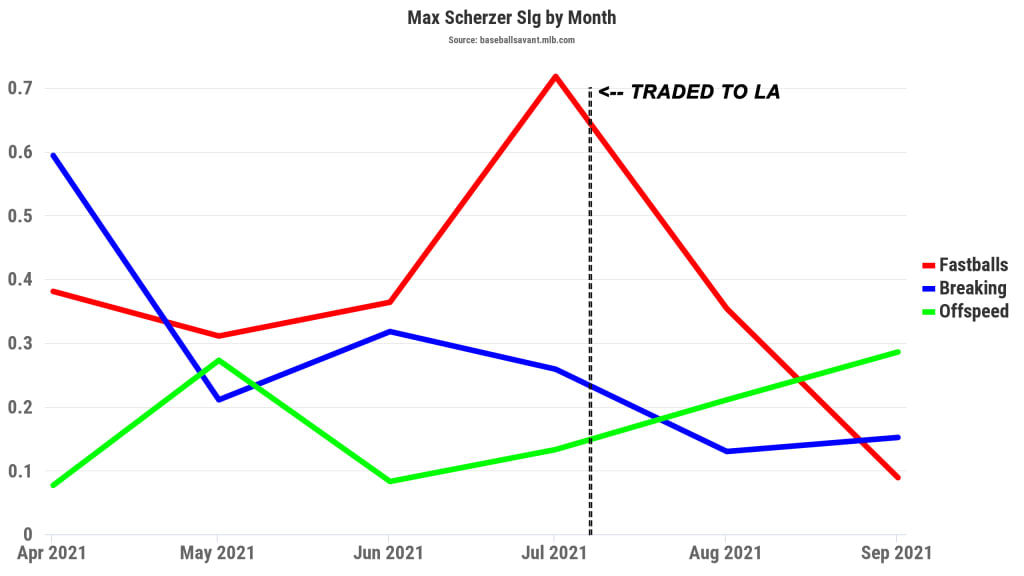

Let’s talk about his pitches. Like most pitchers, Scherzer allows the loudest contact against fastballs, on which he’s allowed a .405 career slugging percentage as opposed to a .320 mark on all other pitches. If you look at his monthly slugging percentage allowed over the course of the 2021 season, it’s pretty clear to see that hitters aren’t squaring up those fastballs (in red) nearly as well since he came to Los Angeles.

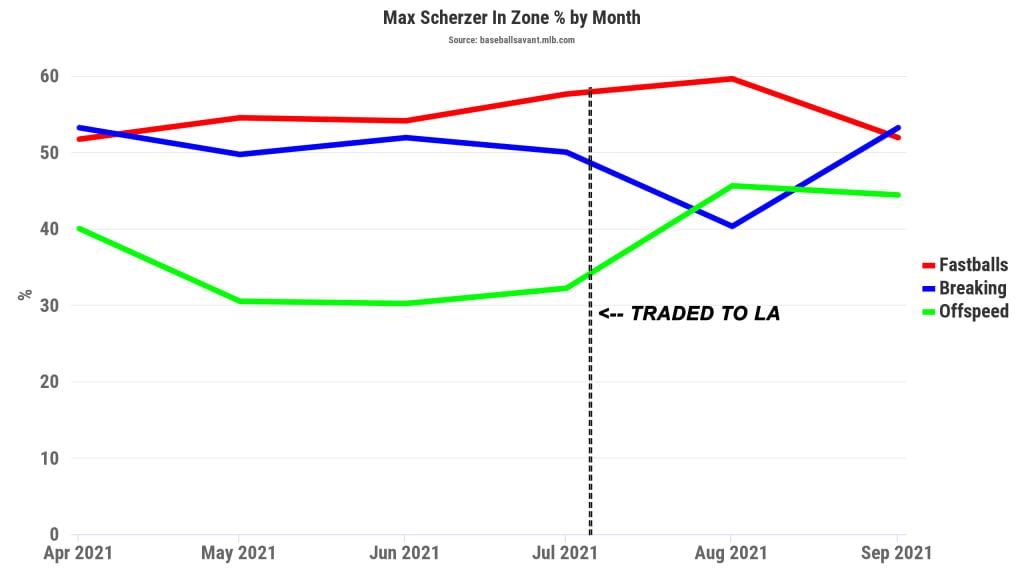

It’s also clear he’s throwing his other pitches for strikes more often. Not only is he throwing his breaking balls -- that’s slider and curve -- more than every single other month of his career save for September of 2016, this September, he’s putting them and his offspeed pitches into the zone more often, too, which explains some of the decrease in walks:

He’s been talking about the difference, too.

“I just had a good feel for [the curveball] today,” Scherzer said on Saturday. “Every pitch plays off each other. Every pitch makes every other pitch better. So … if I can be on with my curveball, that makes every other pitch good. All pitches play off each other, and then it comes down to sequencing, how you mix and match and when you use it -- when you're hard, soft, behind the count, ahead of the count. That's my game -- to be able to throw any pitch at any time.”

That sounds a lot like what he said three weeks ago.

“I was just able to sequence,” Scherzer said on Aug. 27. “I got in a good rhythm with [Austin Barnes] behind the plate and was just able to execute any pitch at any time.”

This, again, is something he’s done for years; it’s not like he’s only just been outstanding for the past few weeks. But something is a little different here with Los Angeles, and you can see it a little in the non-fastballs in the zone.

You can see it a little in the sequencing, too, as he alluded to. With the Nationals this year, just about one-quarter of his pitches (23%) were thrown in groups of three or more consecutive pitches of the same type -- that is, cutter/cutter/cutter, or curve/curve/curve, or so on. (Like when he threw Jazz Chisholm Jr. five straight four-seamers, the last of which Chisholm tripled on.) With the Dodgers, that’s happened only 15% of the time.

It’s too simplistic to put undo emphasis on that, but it’s clearly something he’s talked about, and you can see what it looks like when it works:

“He has been so efficient lately,” said Turner. “In the past, he’d have his games where he’d throw 100 pitches in six innings and have to grind it out. But I feel like the last few starts, he’s been so efficient and still striking people out.”

Scherzer is throwing his secondary pitches in the zone more, and he’s sequencing a little differently, and he’s simultaneously been better than he was and pitching over his head, because not even future Hall of Famers get to pitch to a 0.78 ERA indefinitely. But that speaks a little to why it’s so hard to see That One Obvious Difference, too. Scherzer was already one of the best to ever do it. There’s only so much better you can be.