Are the Tampa Bay Rays a great defensive team?

They sure looked that way in their American League Championship Series victory over the Astros, making play after play after play, and particularly frustrating Alex Bregman, who in Game 3 became just the sixth player in the Statcast tracking era (2015-present) to hit five balls with an exit velocity above 95 mph in a game and have none of them turn into hits.

“I think our defense is just good,” Tampa Bay manager Kevin Cash said after Game 3. “We played just tremendous defense all season long. It’s a credit to the guys and how hard they work at it, whether it’s the outfield, the infield or the catchers.”

Perhaps so. Yet the way that they always, always seemed to be in the right place at the right time made it feel like they had 25 defenders on the field, that they always knew exactly where to have their fielders.

Cash alluded to that before Game 4, saying "they’re hitting some rockets and for whatever reason we’re right where -- so far -- their balls have been going."

Exactly. But how, exactly? Great luck? Outstanding positioning? The realization that anything can happen over a few games? It's probably all of that, to some extent. After all, the Rays had allowed 41 hits and 24 runs to the Yankees in a five-game AL Division Series -- albeit against a stronger offense, to be fair -- and no one was crowing about their defense then.

Still, this all happened, it was a big part of their series victory, and it's something we'll all be watching for in the World Series. So what happened? Let's find out.

How good were they in the regular season?

Good! We think? Obviously, different ways of evaluating defense will tell you different stories. We're comfortable saying "solidly above-average, but not elite."

Outs Above Average:* +3, 13th

Defensive runs saved:* +12, eighth

Ultimate Zone Rating:* +5.3, sixth

Defensive efficiency: .693, 18th

BABIP allowed on grounders: .245, 21st

BABIP allowed on non-homer hard-hit balls: .422, 13th

(*For each of these, we are looking only at the range portion of these metrics, not including value created by throwing arms. The Rays are very good on that -- both of these rate them as baseball's best -- but we're trying to focus on batted balls converted into outs here.)

Obviously, a lot of this is simply due to the presence of Kevin Kiermaier, a three-time Gold Glove Award winner who routinely impresses both the metrics and the eye test. (The Rays' outfield was second in Outs Above Average this year, at +8, and is fourth over the last four years, at +49.) But it wasn't just him against the Astros. It was a team effort.

Regardless, the regular-season Rays were a solid defense, not necessarily an elite one. What about October?

How good have they been in the playoffs?

Amazing, according to the eye test. As far as the numbers go, there really isn't any such thing as playoff-specific OAA, DRS, etc., so let's just look at a few ways of "turning balls in play into outs."

Well, that's interesting. They're not better than the regular season on turning grounders into outs. They're worse, though they have improved in turning hard-hit balls into outs. If you're now thinking, well, this is just specific to the ALCS, then note that their batting average allowed on grounders in October looks like this, split by series: .235 vs. Toronto, .192 vs. New York ... and .303 vs. Houston.

That's because there were hits against them in the ALCS, even if it seems like there haven't been. (Houston hit .260/.350/.401 with a .751 OPS, in the ALCS, after posting just a .240/.312/.408 with a .720 OPS, in the regular season.) Here's a ground-ball single, and another, and another, and another. Here's about two dozen more. Here's George Springer beating the shift to score two, and here's Carlos Correa poking one through for two more.

So why does it seem like it has been so dominant? Perhaps because of the lack of mistakes; Tampa Bay made just one error against Houston, and none by regular position players, since that one miscue was by a pitcher, Aaron Slegers. When there's a play that realistically could be made, they've made it. That's worth a lot, because there's tremendous value in just "making the plays you need to make." Maybe it's because there were so, so many double plays off of batted balls -- 11, to be exact.

Still, there have been so many nice-looking plays, so let's dig deeper. We're going to find a handful of the most noteworthy Rays defensive plays from the ALCS. (It wasn't easy to narrow them down from our original list of nearly 20, which says a lot.)

We'll do this a little subjectively, combining ones that "looked great" with ones that the numbers say were unlikely to be made -- in some cases, those overlap -- and we'll try comparing positioning on those plays to what that hitter generally saw over the course of the season. It's not a perfect method, but it should help us get a little closer to what we saw, or what the Rays might have been thinking.

Basically, are the Rays doing something better than everyone else, or is this a case of a good team making their best plays at the right time?

Game 1: Tucker lines into an unassisted double play [video]

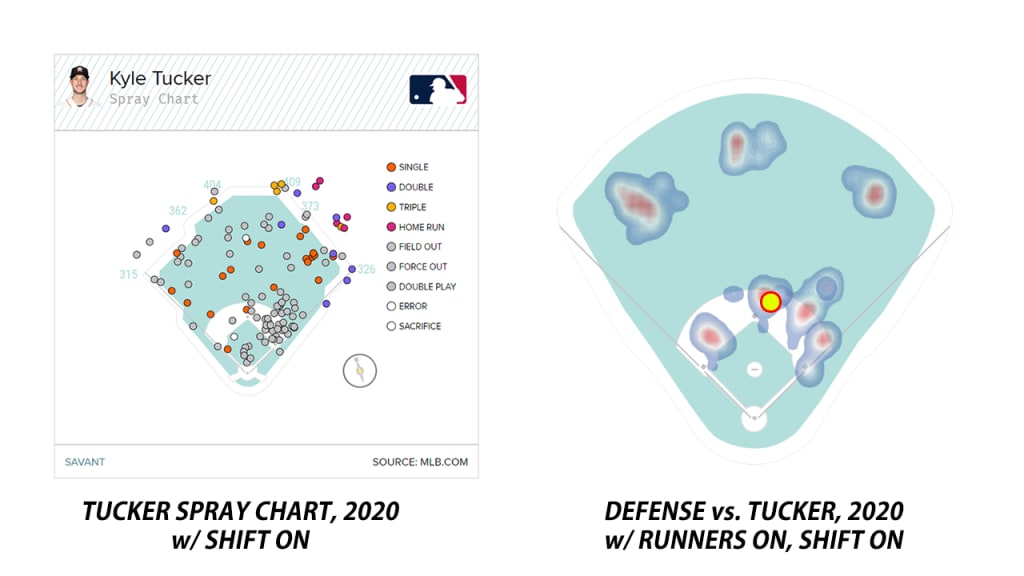

The Rays were down 1-0 in the fourth inning of the series opener, and Blake Snell had allowed two runners to reach before Kyle Tucker hit a line drive up the middle ... right into the waiting glove of Willy Adames, who then doubled Bregman off second. This was a pretty traditional shift against a hitter who gets shifted against often; at 72 percent of pitches seen, Tucker was shifted more often than any Houston batter this year. (He was shifted against a nearly-identical 69 percent of pitches in the ALCS.)

So of course you shift him here and, when you look at where Adames was playing -- where he caught the ball is that yellow dot -- it was more or less exactly where most teams put an infielder against Tucker with the shift on and runners on in 2020:

In the playoffs, Tucker spent most of his time against the shift hitting the ball right up the middle. This is going to be a recurring theme, really. Did the Rays do something special, or were they doing what any intelligent team should be doing in this situation against this hitter?

Verdict: Good positioning, excellent reaction to tag second, but not unique against Tucker

Game 2: Lowe turns Springer liner into double play [video]

In the ninth inning of Game 2, the Astros were down 4-1, but they had loaded the bases with nobody out. George Springer came up against Nick Anderson and squared a ball up -- not necessarily hit that hard, at 87.1 mph, but one that's a hit slightly more than half the time -- to the left of second base. If it goes through, as it probably does for most of baseball history, it scores at least one run, and possibly two. It might change the complexion of the entire series.

Instead, second baseman Brandon Lowe was perfectly positioned to the shortstop side of the bag. He caught the ball on a bounce, took four steps to second base to force out Myles Straw, then calmly completed the 4-3 DP. Yuli Gurriel scored, but the Astros would lose, 4-2.

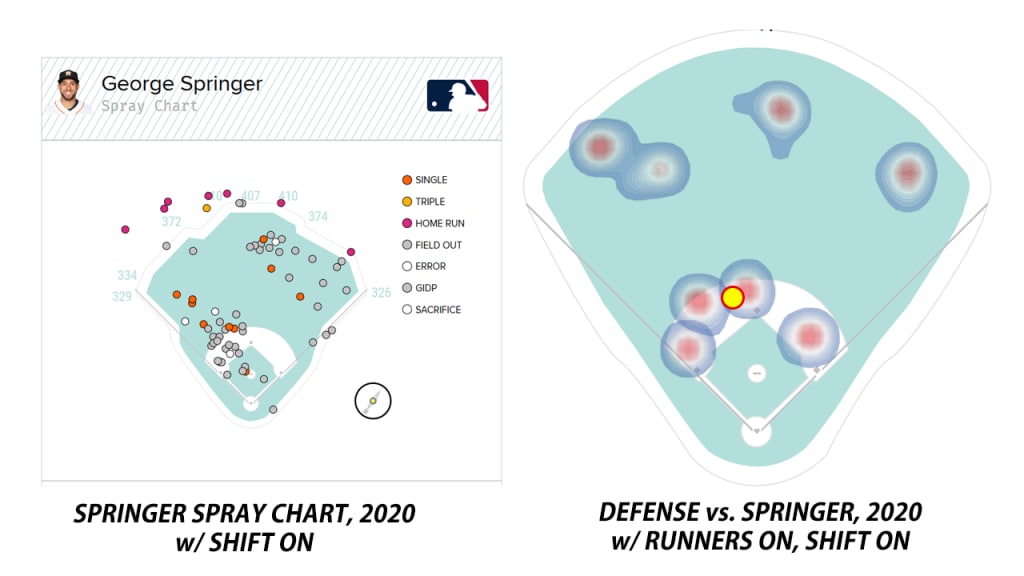

There's no doubt that intelligent, data-driven positioning put Lowe in the right spot. As with Tucker, is this established process against Springer? A look at his spray chart against the shift, and opposing defenses against him, helps give the answer:

If not for the fact that you need a first baseman to cover the most important base, there's almost no reason to have an infielder to the right side against Springer at all. Besides, it's not hard to find other examples of this positioning against Springer turning balls into outs. Just look here, or here, or here. It'd be weirder if they didn't position against Springer this way than if they did.

Verdict: Good positioning, but not unique against Springer

Game 2: Bregman scorches an out to Adames [video]

Poor Bregman, who, after hitting into 20 hard-hit outs in the regular season (hard-hit being 95 mph or more of exit velocity) then did so 11 times in the postseason. A lot of them looked like this one, where a blasted 106.8 mph line drive with runners at the corners in a scoreless game went directly to a fielder, in this case shortstop Adames.

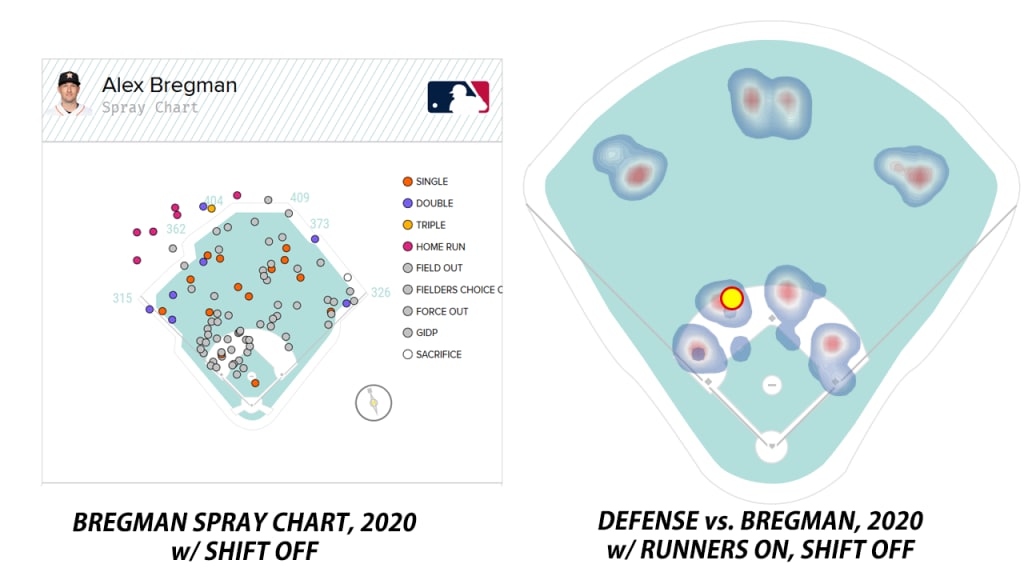

This one looks like perfect positioning. Maybe it was. It also looks somewhat ... traditional?

Adames was positioned 142 feet from the plate, and 14 degrees to the left of second base. (Imagine 0 degrees being straight from home plate to center, and the two foul lines being 45 degrees in either direction.) The average shortstop this year, against a righty batter with no shift on and more than just a runner on first, was 145 feet and 11 degrees, so a little deeper and closer to second than Adames. Rays shortstops (primarily Adames and Joey Wendle) were more like 142 feet and 17 degrees, so shallower and further away from second.

On this play, Adames was as deep as he usually is, and splitting the difference between his usual spot and the usual average shortstop spot. We're only talking about a few feet, but on a ball hit that hard, that matters. Still, this is what you do against Bregman:

Verdict: Good positioning, but not unique against Bregman

Game 2: Margot jumps the wall [video]

There's actually not a whole lot to say about this one other than "wow," though we're including it here because it's difficult to write an article about great defense and not show this play. Let's go ahead and do that right now:

Wow!

It's hard to say a whole lot about positioning here, given that the 6.4 seconds Manuel Margot had to get there is an eternity in baseball time, and "tumbling over the short wall in foul territory" is not exactly "being in the right spot at the right time." If it matters, right fielders against Springer with a righty on the mound this year started 298 feet deep, while Margot was 290, but it really doesn't matter. This one is all about an incredible effort and result.

Verdict: The type of great play fielders rarely even get the chance to attempt.

Game 3: Kiermaier's diving catch [video]

The Astros were down 2-0 in the series and up 1-0 in the third inning of Game 3, with two on and two out, when Correa hit a soft liner into center field. Kiermaier rushed in to make a diving catch and prevent the Astros from blowing it open. Tampa Bay would come back to win, 5-2.

When a lefty pitcher was on the mound, as Ryan Yarbrough was here, the average center fielder played Correa 330 feet deep. In the 2020 regular season, when Kiermaier was playing center field with a lefty pitcher facing a righty hitter, he was, on average, 319 feet deep. But Kiermaier, on this play, was positioned ... 330 feet deep. That may sound like smart positioning, and maybe on aggregate it was, but since this ball went 300 feet, it actually put him in a worse spot.

Still, Kiermaier doesn't have a reputation as a defensive legend for no reason. Thanks in part to his elite reactions -- his jump was +6.1 feet better in the right direction than average, meaning a merely average jump might not have allowed him to even be in position to dive -- he covered 64 feet in 3.8 seconds, converting a 20 percent catch probability play. This was an outstanding play, and one that was more notable than his first-inning rob of Bregman, a nice-looking play that was probably not as hard as Kiermaier made it seem to be. This one, though? Spectacular.

"Taking a run away is just as valuable as driving one in. I guess I’m biased towards that,” Kiermaier said, “because defense is my bread and butter, but it really is.”

Verdict: Kiermaier is a superstar defender. Few outfielders get to this ball.

Game 3: Adames and Díaz team up to rob Altuve [video]

"Back-handed by Adames, he was well-positioned," the TBS broadcast said that night, "throw to first, what a pick by [Yandy] Díaz!"

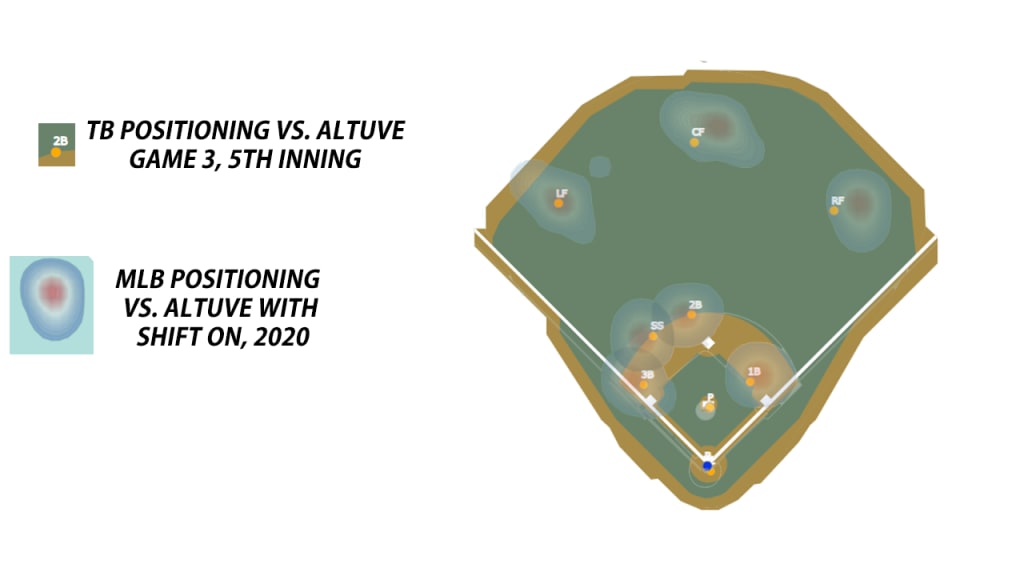

Let's show this one a little differently. Instead of looking at Jose Altuve's spray charts -- though you can do so here -- let's overlay the exact positioning of the Rays infielders on this play against what Altuve saw in 2020 from everyone, at least in plays where the shift was on. In the infield, it is almost an exact match.

There's credit due to Adames, who had to throw the ball 145 feet -- he got up to 128 before the first bounce -- with his momentum headed in the wrong direction with a fast runner hustling. There's credit to a nice pick by Díaz, who played only 14 innings at first base this year, fifth most on the Rays.

But this is where assigning credit for positioning gets tricky. Did the Rays break the secret code, or did they just do exactly the data suggested they did, and that most every team had done when shifting against Altuve this year anyway? Maybe it's that part, the when shifting against Altuve, that's important.

Shifts seen by Altuve, 2020 (percentage of pitches seen)

Regular season -- 17 percent

ALWC vs. Twins -- 63 percent

ALDS vs. A's -- 0 percent

ALCS vs. Rays -- 53 percent

Well, isn't that interesting? It seems the Twins and Rays had similar ideas, though it didn't stop Altuve from slugging .885 against Tampa Bay. It might have helped him lose a hit here, but so did the great play of the two fielders involved.

Verdict: The coaches called the shift. Adames and Díaz made the nice plays. This is a team effort.

Game 7: Adames robs Bregman, again [video]

If you were to only have seen the ALCS, you might think that Adames is the best defensive shortstop in baseball. That's not really true; he was slightly above-average by DRS, and surprisingly below-average by OAA. (Interestingly, after an .813 OPS during the season, he has only a .550 OPS in the playoffs.)

But for the last week, he has looked like an absolute fielding superstar, and he showed it again in Game 7, taking yet another hit away from Bregman.

Bregman, again, was not being shifted against, and Adames was playing eight feet deeper than he was when he caught Bregman's Game 2 lineout, examined above. While that was also against Charlie Morton, that one came with two runners on; for this one, Adames was 150 feet deep, about equal to the 148 feet deep that shortstops routinely played Bregman with a righty pitching and no runners on.

While this is clearly a very nice play by Adames, the most interesting part may be what you can't see clearly on the video -- Bregman was absolutely flying. His 28.8 feet per second sprint speed was his fastest of the postseason and second fastest of the entire 2020 season.

Verdict: Adames is a good-enough defensive shortstop who is playing out of his mind this week.

So: Where does this all leave us?

There were plenty of other plays, including an outstanding catch by Hunter Renfroe, and we didn't even get to anything by Wendle. (Just look at how many balls the Astros pounded to the traditional third-base spot, which may get into something we didn't explore here -- positioning might also be about an excellent pitching plan to induce the right kind of hits, not just about where fielders are standing.

Ultimately, there's not one answer here. The Rays were always in the right spot, except for the times they weren't, and much of their seemingly elite positioning seems to match what other teams did against Astros hitters this year. Maybe it just looked better considering Altuve was making multiple costly errors, providing a stark contrast between the two teams.

At the end of the day, the largest credit comes down to the players on the field. Tampa Bay fielders made almost no mistakes against the Astros; they played nearly flawless baseball. For a team that didn't actually hit that well outside of Randy Arozarena, it wasn't just a welcome boost, it was a necessary force. If defenses can have a hot streak, this was it.

Now: Can they keep it up for one more week? It might help decide the World Series.