A version of this story originally ran in March 2021.

Go ahead and think about it: What's the longest home run in baseball history? What's the first tater-shattering, gravity-defying, ear-splitting blast that comes to your mind?

Maybe it's the Sultan of Swat, the King of Crash. Babe Ruth had a bunch of moonshots over his baseball-wrecking career. Some ended up in alligator ponds, some cleared fence after fence after fence until there were no more fences left to clear.

What about Mickey Mantle? There are stories of his 600-foot home runs or treating old Yankee Stadium like it was his own personal Little League field.

There's home run king Barry Bonds, there's Adam Dunn depositing baseballs into other states. There's the unbelievable power of Wily Mo Peña or Glenallen Hill.

But what if I told you the guy who has the longest home run ever barely even played in the Major Leagues? What if I told you he's currently working a regular day job way out in Maui and never even talks about it?

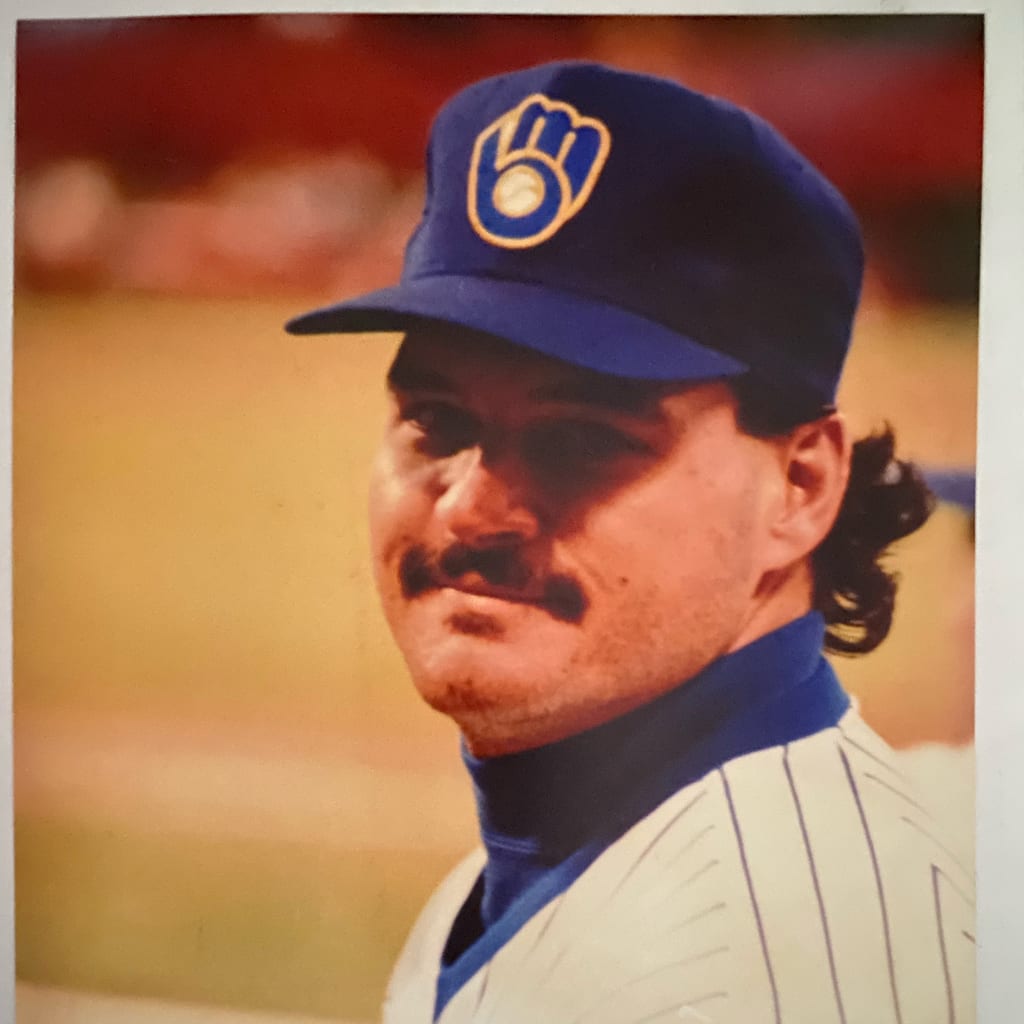

If you Google "longest home run ever hit," the search pops up on Joey Meyer. The Hawaii native hit just 18 homers in 156 games with the Brewers between 1988 and 1989, but, standing at a giant 6-foot-3, 260 pounds, he was a big-time power threat in the Minors. Meyer hit 135 homers over 580 games.

And on one magical night, in the thin air of Mile High Stadium, he hit one to the moon.

"No, I don't even tell them I played," Meyer said with a laugh in a phone interview with MLB.com, his work walkie-talkie blaring in the background. He works security at a hospital in Maui. "I've been working at this job for five years and I don't tell anybody."

It all happened the night of June 2, 1987. Meyer's Denver Zephyrs -- the Triple-A affiliate of the Brewers -- were taking on the Buffalo Bisons at Mile High Stadium. The giant football/baseball stadium could hold about 70,000, but just a little over 1,000 people were in attendance. Meyer, 25, had been slugging his way through the Minors the past few years. He hit 91 homers from 1984-86, batting around .300 and cracking 100 RBIs twice. He was a big prospect with a big frame. According to the New York Times, the team couldn't even find a jersey to fit his torso that season.

"When the Zephyrs needed a uniform shirt for Meyer a year ago, the only one big enough was a souvenir shirt in a Denver sports bar," Dave Anderson wrote.

Meyer's high school coach in Honolulu still raves about his power, saying he could come out right now and still hit homers. The first baseman was even given the Barry Bonds treatment in his school days, getting intentionally walked with the bases loaded.

"Yeah I always hit home runs, but I prided myself that at every level I played, I hit for average," Meyer said.

When Meyer came up for the at-bat in question that night, he had already homered. But players on the field thought it had only gone out because of the thin Rocky Mountain air.

"The first one I hit barely went over the fence, so everybody on the other team was yelling cheapie and all that," Meyer said. "The next one, though, was that one."

Meyer reared back and connected with a breaking ball from reliever Mike Murphy -- sending it deep into the Denver darkness. The ball kept going up and up until it hit halfway up the second deck of Mile High Stadium -- a place very few baseballs go. If you watch the video, the camera can't even follow it that high. Meyer admits he never saw where it landed.

"Well, I knew I hit it good," Meyer told me. "In the thin air, it doesn't take much. But I didn't watch it, you know. I wasn't the watching type. When I hit third base [third-base coach/manager] Terry Bevington is the one who told me, 'You went into the upper deck.' I high-fived him and thought he was joking."

Meyer had hit BP balls up there but never in a game. Nobody had ever done it in a game. A perfect swing, the high altitude and maybe, just maybe, the bat he used all played a role.

"A new player had come in from Baltimore, Donnie Scott," Meyer said. (Scott was traded from Rochester, the Orioles' Triple-A affiliate at the time.) "He had Cal Ripken's bats. He liked my bats, so I traded him my bat for a Cal Ripken bat. That's the bat I used that night."

Meyer ended up hitting three home runs that night with Ripken's lumber. He then used it the next day, and in his first plate appearance, it broke.

"Everybody told me don't use it again, but of course I did," Meyer said.

The media descended on Mile High the next day -- wanting to talk to the man who reached heights never reached before. You get the feeling Meyer, modest and soft-spoken over the phone, was almost frightened by the attention. Overwhelmed by his own power.

"The following day, there were so many reporters there," Meyer recalled. "When you're not used to that many reporters and all of their things tied together in front of you, you know, their microphones. It's pretty intimidating."

The homer also needed to be officially measured, so the team called in the best possible person they could: City of Denver engineer Jerry Tennyson.

"I don't know why they decided to [call me]," Tennyson told me over the phone. "I'm not much of a baseball fan, don't know much about it, didn't know much about it. But they just asked me to come in and told me this is where it hit and it seems like it could be a hell of a long ways. I calculated it without ever knowing any records of any kind."

Tennyson was shocked when I told him it's considered perhaps the longest measured home run in the history of baseball, telling me multiple times "that's incredible." One of his responsibilities was laying out the foundations for the football and baseball fields at Mile High Stadium, so he was very familiar with the grounds and dimensions.

"There were people who worked at the stadium full-time," Tennyson explained. "What we did was took what their line of sight was of the baseball at its highest arc and where it hit in the east stands. And I just calculated it from there. I don't remember how I actually came up with the calculations -- it involved the speed of the baseball, what kind of arc it was on, where it landed in the east stands and where it may have been projected beyond that point."

The event did happen more than 34 years ago, so it's hard to fault Tennyson for not remembering exactly how he got the number 582. Not being a fan of baseball, he also said he was just focused on getting an exact measurement and not taking home run history into consideration at all. He wasn't trying to "memorialize it." He did say a University of Colorado professor called him shortly after the measurements came out and agreed with how he came up with the distance.

So, there you have it: the longest verifiably measured homer in history.

Akin to the Ted Williams seat at Fenway Park, the chair at Mile High was removed for an orange (or maybe green?) one and the original may be on some racetrack in Pueblo, Colo. But that's a whole other insane story.

As for Meyer -- he started the '88 season with the Brewers. But his power never translated to the big leagues and he was back part-time in the Minors the next year before leaving pro baseball in 1991 at the age of 29. He did have some other special moments: He's the only player to ever hit a walk-off homer off Roger Clemens, and he belted 26 homers in 104 games during one season in Japan.

Meyer said he hasn't really thought about the homer too much until the last few years. He was more just disappointed he didn't make it in the Majors for longer.

"It's special to see it. Now I'm 58, I appreciate more things now than I did," he told me. "When I was done playing, I didn't do what I wanted and expected to do: play in the big leagues longer, establish myself. It was abrupt. I appreciate things more now than I did a few years ago."

Unlike some other mammoth homers in baseball history, there are only a handful of stories on Meyer's blast -- the longest ever according to the internet. He seems content with that -- helping out a little bit at MLB clinics on the island and really not talking about his baseball career unless somebody finds out about it.

"It's an honor for you to even call me," Meyer said. "It's been so many years, at least I'm remembered for something."