The Rays are the team that introduced "the opener" to baseball, just over a year ago. They're the team that a decade ago reintroduced the four-man outfield to the game, and popularized regular infield shifts before that was a strategy you saw on a nightly basis. They were among the first to hire Wall Street types to run baseball teams, and they were the team that gave Evan Longoria a nine-year contract six games into his career.

The Rays, for a lot of reasons, have specialized in being just a little weird, though it's a little unfair to focus on that over their current success, sitting as they are atop the standings in the American League East, while possessing one of the best records in baseball.

Yet here they are again, doing something odd. The Rays just finished off the month of April doing something we have just about never seen, at least in the five seasons of Statcast tracking: In the first month of the season, they shifted right-handed batters more (33 percent of the time) than they shifted left-handed batters (26.9 percent).

If that feels weird ... well, it is. It's not that it's never happened, it's just that it's almost never happened.

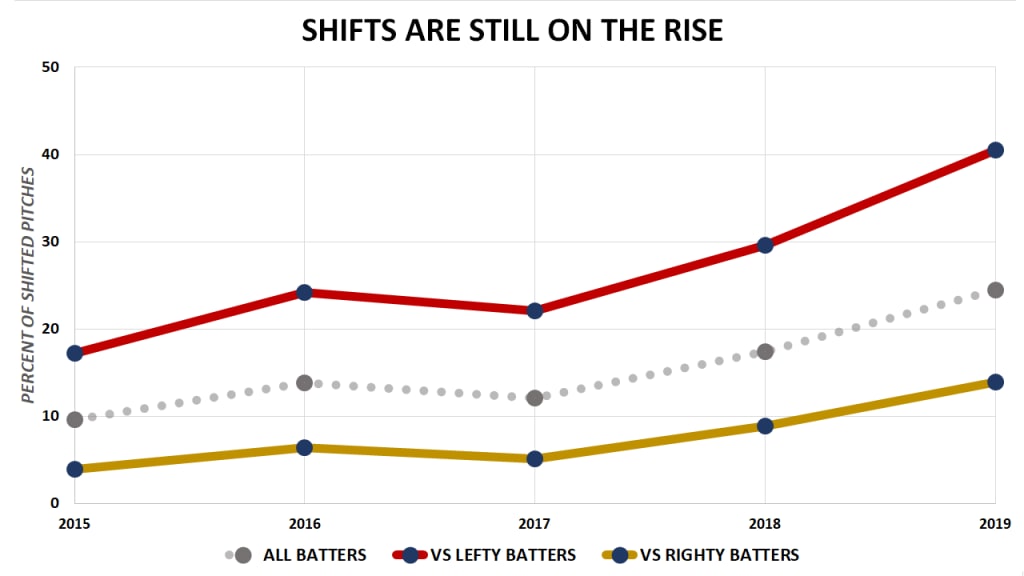

As you'd expect, shifts have been on the rise in recent seasons, and as you'd further expect, Major League teams shift against lefty batters far more than they do against righty batters. (That's a gap that's actually been increasing; in 2015, the Majors shifted against lefties by 7.6 percentage points more than they did against righties; so far this year, lefties are seeing shifts 16 percentage points more often than righties.)

Yet the Rays are doing the opposite, at least in the early going.

“We did it a lot last year," Rays manager Kevin Cash said to MLB.com's Juan Toribio. "It was surprising to me that it wasn’t talked about as much, because I don’t know if it was equal lefty to righty, but it was sure close, and this year, it feels like it’s been close to equal, also.”

Cash is correct, sort of. No team in 2018 shifted against righties more than Tampa Bay did, deploying it on 28 percent of pitches to righties, far more than the 9.8 percent Major League average. (One team, the Angels, didn't shift at all against a righty in 2018. They went nearly two full years without doing so, before breaking their streak on Opening Day this season.)

But the difference there is that even with all the righty shifts in 2018, it still didn't compare to their lefty shifts. The Majors shifted lefties 12 percentage points more than they did righties last year. The Rays shifted lefties 17 points more.

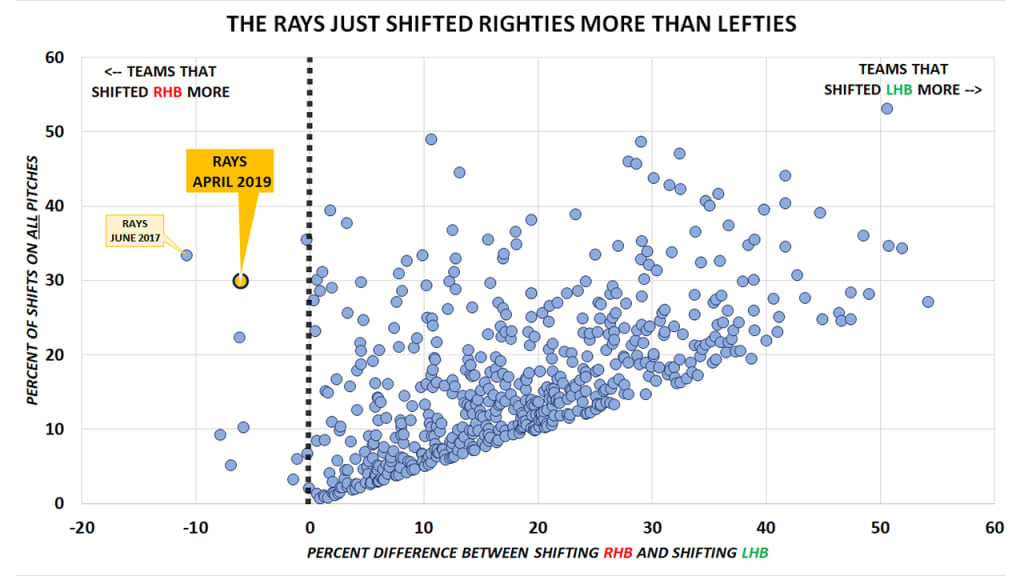

What they did in this year's first month -- and we'll be combining the last few days of March with April from here on out -- is something else. To try to see how rare this was, we went back month-by-month, team-by-team, from the start of 2015 through April 2019. This accounts for 570 different team months.

Overwhelmingly, teams have shifted lefties more than righties, by which we mean more than 98 percent of the time. A few of the remaining 2 percent were essentially lefty/righty ties or were within 2 percent either way; there have only been six team months, or about 1 percent, where a team shifted righty batters by more than 2 percent.

One of the previous five teams to do it: The Rays, back in June 2017. Of course. (The other four: the Phillies in June 2016, the Braves in July 2016, the Pirates in September 2016 and the Twins in September 2016.)

“We’re going to do it," Cash said, "and we’re going to be aggressive shifting. There is plenty of information out there that suggests that it makes for the right decision and it makes sense to shift those guys."

"We’re not doing it just to do it ... we have enough information that is recommending and suggesting to play that pull side.”

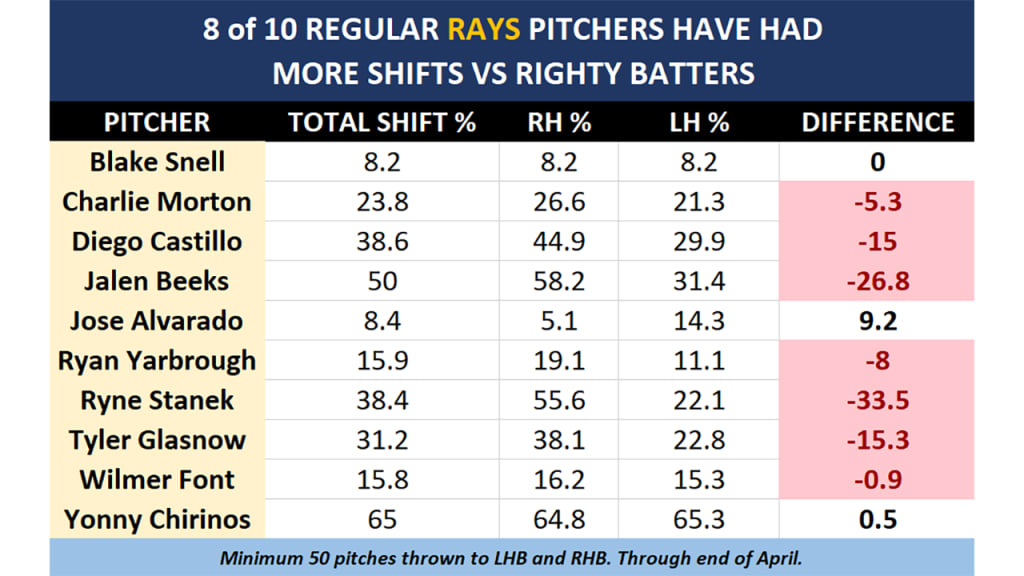

Of the 345 pitchers this year to throw at least 50 pitches to righty batters, four of the five atop the righty shift percentage leaderboard are Rays. (And the fifth used to be.)

Highest right-handed batter shift percentage, 2019 (min. 50 pitches)

64.8 percent -- Yonny Chirinos, TB

63 percent -- Alex Cobb, BAL

58.7 percent -- Emilio Pagan, TB

58.2 percent -- Jalen Beeks, TB

55.6 percent -- Ryne Stanek, TB

Of the 10 Rays pitchers who had thrown 50 pitches against both righties and lefties through the end of April, eight of them had seen more shifts with righty batters than lefty batters -- and Blake Snell was even.

So: It's happening. But why? And is it working?

“I throw so many changeups, so I don’t give up a whole lot of ground balls the other way," said the lefty Beeks, who joined the Rays in a trade for Nathan Eovaldi last summer. "I don’t throw many heaters low and away, that’s not a pitch that I use very often. Most things are going to be pull side against righties or flares the other way, so it makes sense.”

“I notice that they do shift on righties for me, I do notice that. But I didn’t notice they do it with the other pitchers."

Here, for example, is Beeks benefiting from the shift against White Sox outfielder Eloy Jimenez earlier this month.

Here's Yankees third baseman Miguel Andujar, last season, having a sure hit taken away.

If we go back to the start of 2018 -- clearly the Rays didn't just start thinking about this after Opening Day -- you can see what they're getting at. Across the Majors, ground balls from right-handed hitters have been distributed like this:

Pull: 45.6 percent

Straightaway: 40.9 percent

Opposite: 13.6 percent

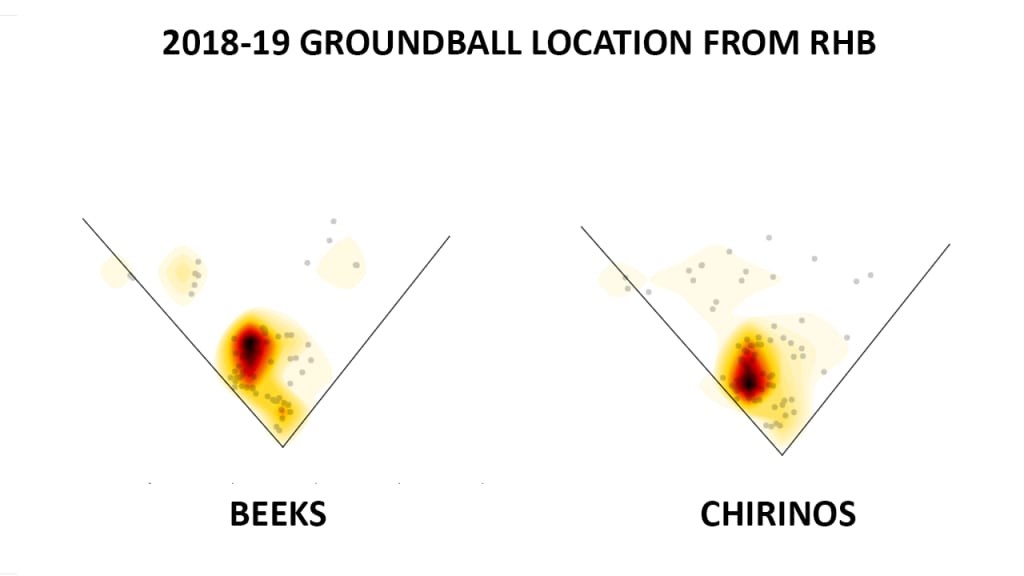

Put another way, nearly 87 percent of grounders from righties are pulled or up the middle, or otherwise "not to the opposite field," as Beeks said. For their part, the Rays are slightly above average there, at 87.3 percent. If shifting is simply about putting fielders where you expect the ball to go, this all tracks. You can see that on a pitcher-level basis when look at 2018-19 grounders from righties against Beeks and Chirinos.

(We're looking at all situations, here, for simplicity; clearly it gets more complicated when we factor in various base/out situations.)

Whether it's actually working is a little less clear. So far this year, the Rays have allowed a .241 average to righties on grounders with the shift on, and a .233 average with the shift off. Their defense has under-performed expectations against right-handed grounders with the shift on, since their expected batting average (which accounts for exit velocity and launch angle, but not direction) is .215, well under that .241. Then again, it's been something similar without the shift on, and either way, this sort of analysis is somewhat unsatisfying because very different types of hitters see (and don't see) shifts.

If anything, this might be less about what's happening against righties and more about what's happening against lefties. Sure, the Rays are shifting righties more than they did last year, but they're also shifting lefties less, down from 36.8 percent to 26.9 percent. As the rest of the Majors are increasing their lefty shift percentage -- in some cases, like the Brewers going from 28.3 percent to 60 percent, by quite a bit -- the Rays are one of only three teams to drop their shift rate against lefties by more than 10 percent.

So it is that Tampa Bay is shifting more against righties than lefties, because that's a very weird thing to do. But it's also that they're just not shifting on lefties quite so much, too. This is a case where the Rays are zigging where others are zagging -- and not for the first time -- just perhaps not in the way we might have thought.

MLB.com's Juan Toribio contributed to the reporting of this article.