History of Black Baseball, Part II

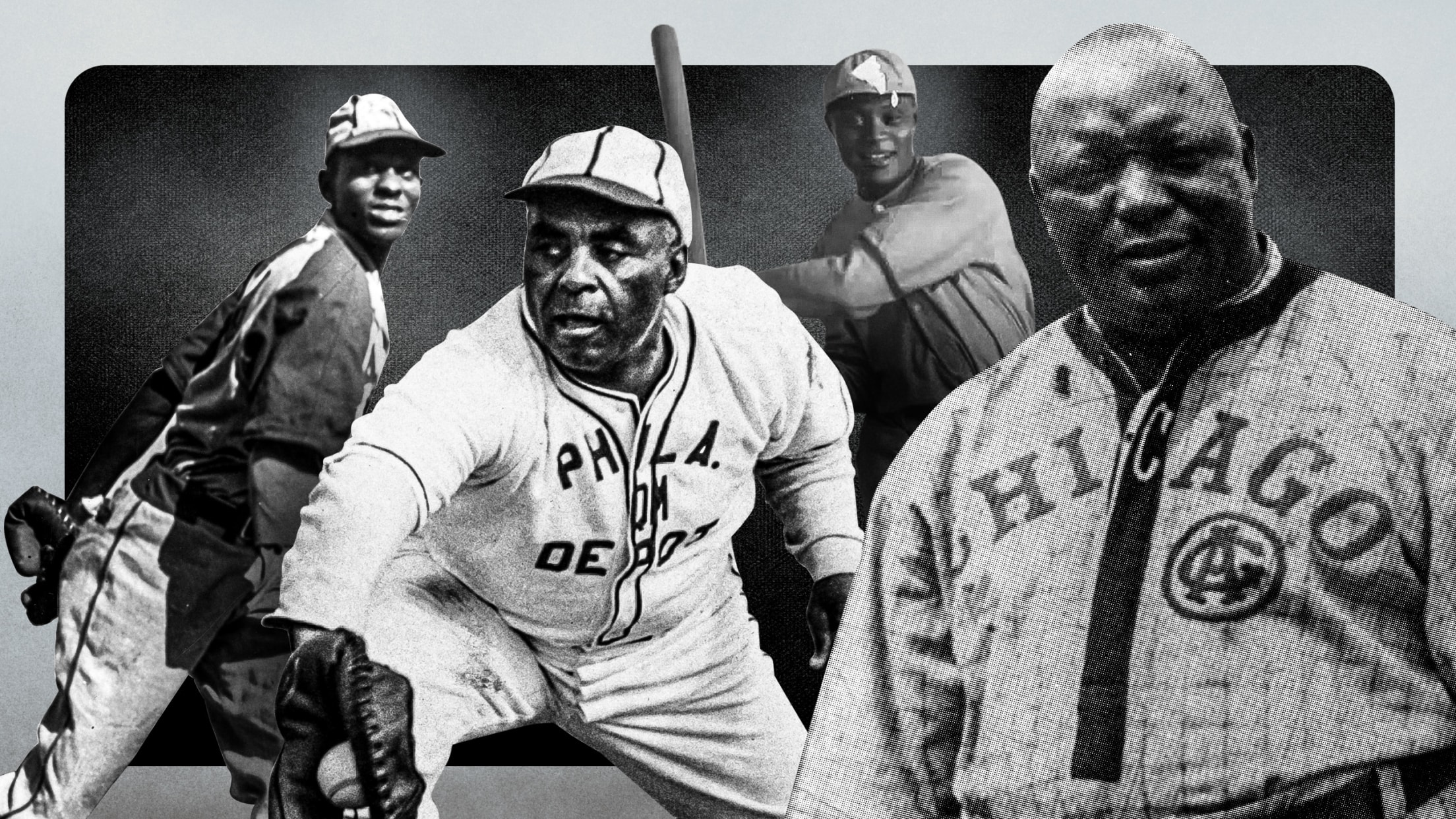

Although most Black people lived in the South, during the first two decades of the 20th century, the great Black teams and players congregated in the metropolises and industrial cities of the North. Chicago emerged as the primary center of Black baseball with teams like the Leland Giants and the Chicago American Giants. In New York, the Lincoln Giants, which boasted pitching stars Smokey Joe Williams and Cannonball Dick Redding, shortstop John Henry Lloyd and catcher Louis Santop, reigned supreme. Other top clubs of the era included the Philadelphia Giants, the Hilldale Club (also of Philadelphia), the Indianapolis ABC’s and the Bacharach Giants of Atlantic City. Player contracts were nonexistent or nonbinding and stars jumped frequently from team to team. “Wherever the money was,” recalled John Henry Lloyd, “that’s where I was.”

Fans and writers often compared the great Black players of this era to their white counterparts. Lloyd, one of the outstanding shortstops and hitters of that or any era, came to be known as “The Black Wagner,” after his white contemporary Honus Wagner, who called it an “honor” and a “privilege” to be compared to the gangling Black infielder. A St. Louis sportswriter once said when asked who was the best player in baseball history, “If you mean in organized baseball, the answer would be Babe Ruth; but if you mean in all baseball. . . the answer would have to be a colored man named John Henry Lloyd.” Pitcher “Rube” Foster earned his nickname by outpitching future Hall of Famer Rube Waddell, and Cuban Jose Mendez was called “The Black Matty” after Christy Mathewson.

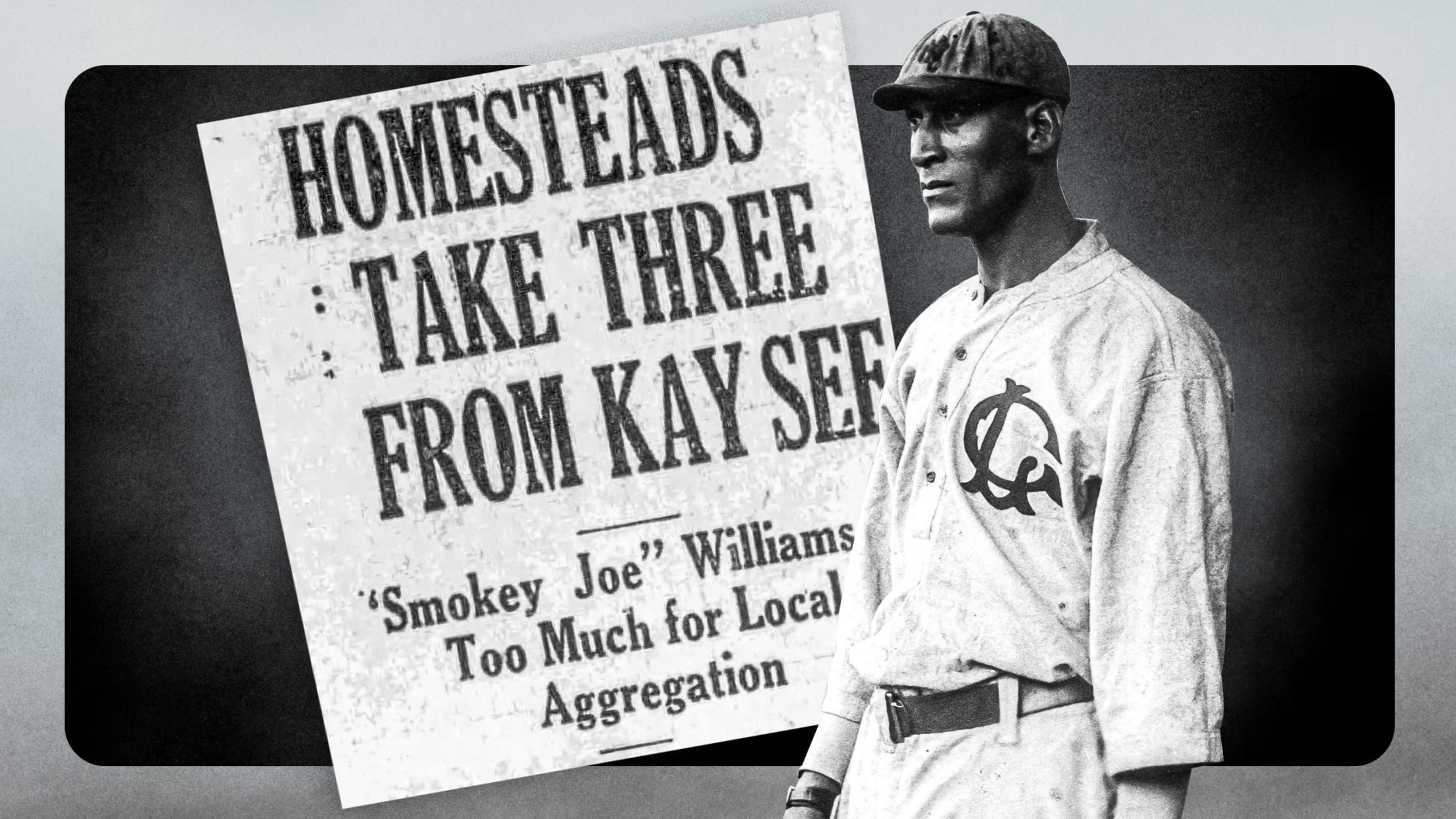

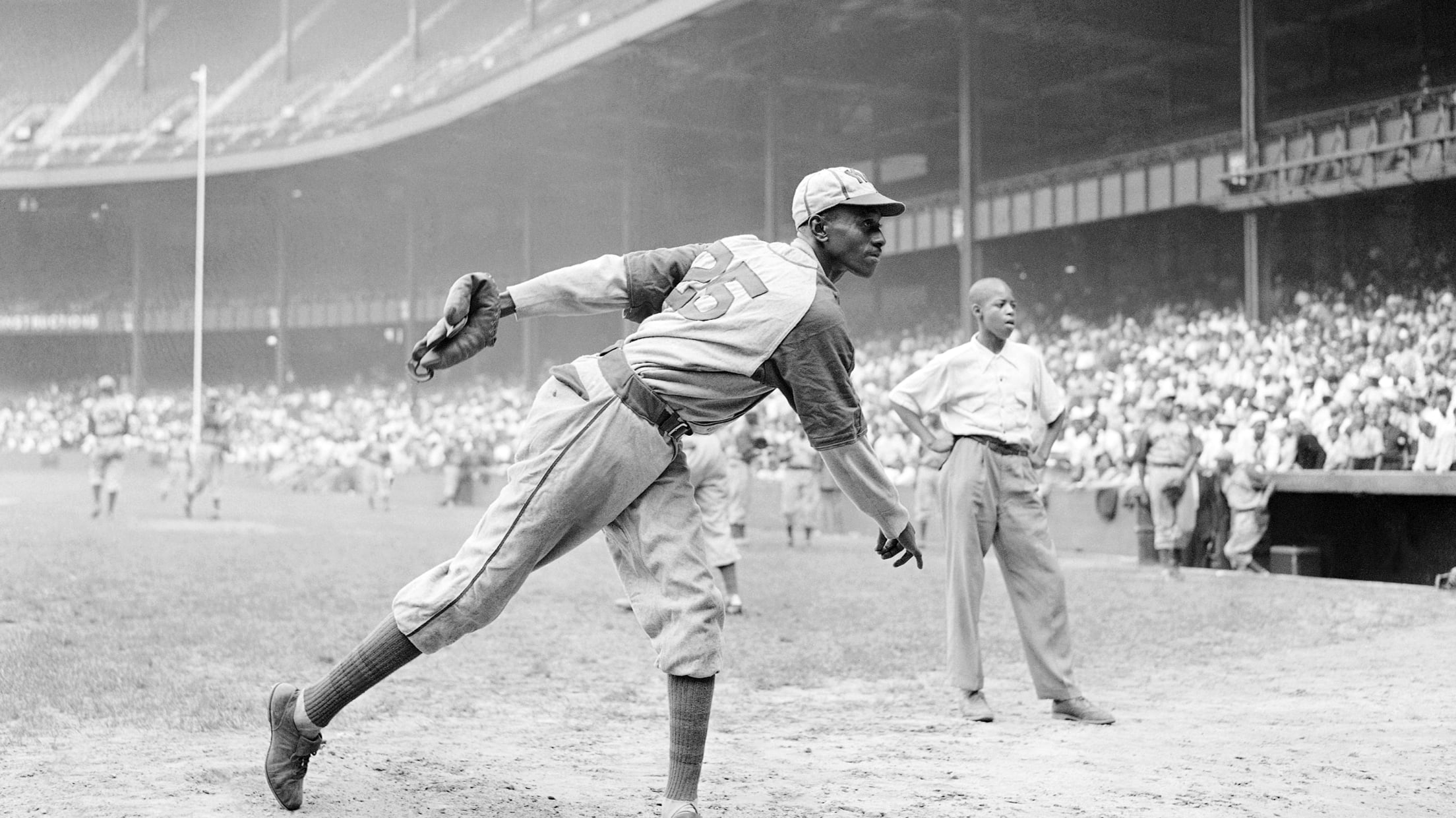

The talents of Foster and Mendez notwithstanding, the greatest Black pitcher of the early twentieth century was 6'5" Smokey Joe Williams. Born in 1886, Williams spent a good part of his career pitching in his native Texas, unheralded until he joined the Leland Giants in 1909 at the age of 24. From 1912–1923 he won renown as a strikeout artist for Harlem’s Lincoln Giants. Against Major League competition Williams won six games, lost four, and tied two, including a three-hit 1–0 victory over the National League champion Philadelphia Phillies in 1915. In 1925, he signed with the Homestead Grays and although approaching his fortieth birthday, starred for seven more seasons. A 1952 poll to name the outstanding Black pitcher of the half-century, placed Williams in first place, ahead of the legendary Satchel Paige.

Oscar Charleston ranks as the greatest outfielder of the 1910s and 1920s. With tremendous speed and a strong, accurate arm, Charleston was the quintessential centerfielder. During his 15-year career starting in 1915, Charleston hit for both power and average and may have been the most popular player of the 1920s. After he retired he managed the Philadelphia Stars, Brooklyn Brown Dodgers, and other clubs.

Several major stars of this era labored outside the usual channels of Black baseball. In 1914, white Kansas City promoter J.L. Wilkinson organized the All-Nations team, which included white players, Black players, Native Americans, Asians, and Latin Americans. Pitchers John Donaldson, Jose Mendez, and Bill Drake and outfielder Cristobel Torriente played for the All-Nations team, described by one observer as “strong enough to give any major league team a nip-and-tuck battle.” A Black Army team from the 25th Infantry Unit in Nogales, Arizona, featured pitcher Bullet Joe Rogan and shortstop Dobie Moore. In 1920, when Wilkinson formed the famed Kansas City Monarchs, the players from the All-Nations and 25th Infantry teams formed the nucleus of his club. In 1921, the Monarchs challenged the minor league Kansas City Blues to a tournament for the city championship. The Blues won the series five games to three. In 1922, however, the Monarchs won five of six games to claim boasting honors in Kansas City. One week later, they swept a doubleheader from the touring Babe Ruth All-Stars.

In the years after 1910, Andrew “Rube” Foster emerged as the dominant figure in Black baseball. Like many of his white contemporaries, Foster rose through the ranks of the national pastime from star player to field manager to club owner. Born in Texas in 1879, Foster accepted an invitation to pitch for Chicago’s Union Giants in 1902. “If you play the best clubs in the land, white clubs as you say,” he told owner Frank Leland, “it will be a case of Greek meeting Greek. I fear nobody.” By 1903, he was hurling for the Cuban X Giants against the Philadelphia Giants in a series billed as the “Colored Championship of the World”. His four victories in a best of nine series clinched the title. The following year, he had switched sides and registered two of three wins for the Philadelphia Giants in a similar matchup, striking out 18 batters in one game and tossing a two-hitter in another. In 1907, he rejoined the Leland Giants and, in 1910, pitched for and managed a reconstituted team of that name to a 123–6 record.

As a pitcher, Foster had ranked among the nation’s best; as a manager, his skills achieved legendary proportions. A master strategist and motivator, Foster’s teams specialized in the bunt, the steal, and the hit-and-run, which came to characterize Black baseball. Fans came to watch him sit on the bench giving signs with a wave of his ever-present pipe. He became the friend and confidant of major league managers like John McGraw. Over the years, Foster trained a generation of Black managers, like Dave Malarcher, Biz Mackey, and Oscar Charleston in the subtleties of the game.

In 1911, Foster entered the ownership ranks, uniting with white saloon keeper John Schorling (the son-in-law of White Sox owner Charles Comiskey) to form the Chicago American Giants. With Schorling’s financial backing, Foster’s managerial acumen, a regular home field in Chicago, and high salaries, the American Giants attracted the best Black players in the nation. Throughout the decade, whether barnstorming or hosting opponents in Chicago, the American Giants came to represent the pinnacle of Black baseball.

By World War One, Foster dominated Black baseball in Chicago and parts of the Midwest. In most other areas, however, white booking agents controlled access to stadiums, and as one newspaperman charged in 1917, “used circus methods to drag a bunch of our best citizens out, only to undergo humiliation . . . while [they sat] back and [grew] rich off a percentage of the proceeds.” In the East, Nat Strong, the part owner of the Brooklyn Royal Giants, Philadelphia Giants, Cuban Stars, Cuban Giants, New York Black Yankees, and the renowned white semi-pro team, the Bushwicks, held a stranglehold on Black competition. To break this monopoly and place the game more firmly under Black control, Foster created the National Association of Professional Baseball Clubs, better known as the Negro National League, in 1920.

Foster’s new organization marked the third attempt of the century to meld Black teams into a viable league. In 1906, the International League of Independent Baseball Clubs, which had four Black and two white teams, struggled through one season characterized by shifting and collapsing franchises. Four years later, Beauregard Moseley, secretary of Chicago’s Leland Giants, attempted to form a National Negro Baseball League, but the association folded before a single game had been played.

The new Negro National League, which included the top teams from Chicago, St. Louis, Detroit, and other Midwestern cities, fared far better. At Foster’s insistence, all clubs, with the exception of the Kansas City Monarchs, whom Foster reluctantly accepted, were controlled by Black owners. J.L. Wilkinson, who owned the Monarchs, a major drawing card, had won the respect of his fellow owners and soon overcame Foster’s reservations. He became the league secretary and Foster’s trusted ally. Operating under the able guidance of Foster and Wilkinson, the league flourished during its early years. In 1923, it attracted 400,000 fans and accumulated $200,000 in gate receipts.

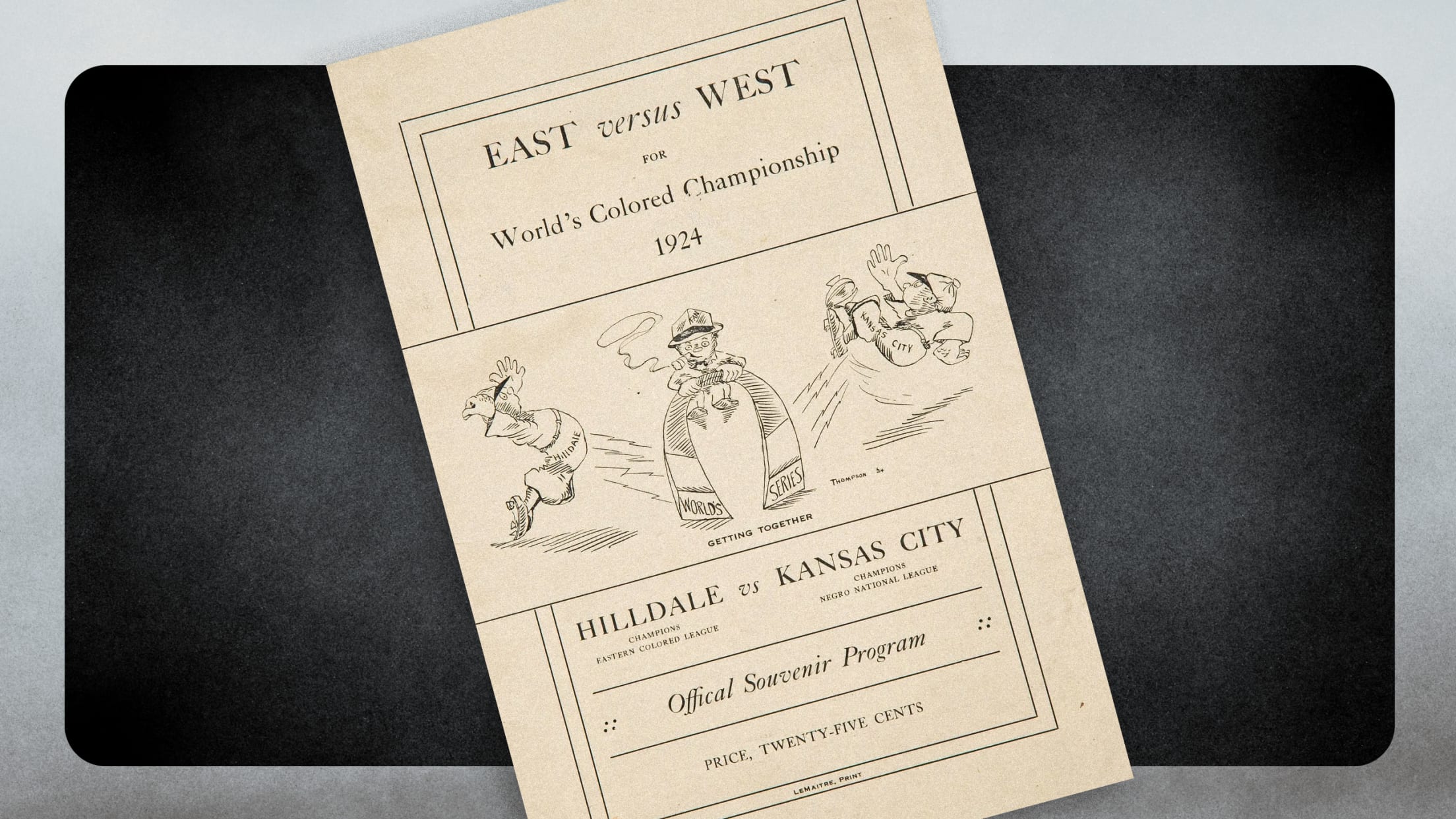

The success of the Negro National League inspired competitors. In 1923, booking agent Nat Strong formed an Eastern Colored League, with teams in New York, Brooklyn, Baltimore, New Jersey, and Philadelphia. With four of the six teams owned by whites, and Strong controlling an erratic schedule, the league had somewhat less legitimacy than Foster’s circuit. Playing in larger population centers, however, the more affluent Eastern clubs successfully raided some of the top players of the Negro National League before the circuits negotiated an uneasy truce in 1924. Throughout the remainder of the decade, however, acrimony rather than harmony characterized interleague relations. A third association emerged in the South, where the stronger independent teams in major cities formed the Southern Negro League. While this group became a breeding ground for top players, the impoverished nature of its clientele, and the inability of clubs to bolster revenues with games against white squads, rendered them unable to prevent their best players from jumping to the higher paying Northern teams.

At their best the Negro Leagues of the 1920s were haphazard affairs. Since most clubs continued to rely on barnstorming for their primary livelihood, scheduling proved difficult. Teams played uneven numbers of games and especially in the Eastern circuit skipped official contests for more lucrative nonleague matchups. Several of the stronger independent teams, like the Homestead Grays, remained unaffiliated. Umpires were often incompetent and lacked authority to control conditions. Finally, players frequently jumped from one franchise to another, peddling their services to the highest bidder. In 1926, Foster grew ill, stripping the Negro National League of his vital leadership. Two years later, the Eastern Colored League disbanded and in 1931, less than a year after Foster’s death, the Negro National League departed the scene, once again leaving Black baseball with no organized structure.

With the collapse of Foster’s Negro National League and the onset of the Great Depression, the always borderline economics of operating a black baseball club grew more precarious. White booking agents, like Philadelphia’s Eddie Gottlieb or Abe Saperstein of the Midwest, again reigned supreme. In the early 1930s, only the stronger independent clubs like the Homestead Grays or Kansas City Monarchs, novelty acts like the Cincinnati Clowns, or those teams backed by the “numbers kings” of the black ghettos could survive.

The Kansas City Monarchs emerged as the healthiest holdover from the old Negro National League. In 1929, owner Wilkinson had commissioned an Omaha, Nebraska, company to design a portable lighting system for night games. The equipment, consisting of a 250-horsepower motor and a 100-kilowatt generator, which illuminated lights atop telescoping poles 50 feet above the field, took about two hours to assemble. To pay for the innovation, Wilkinson mortgaged everything he owned and took in Kansas City businessman Tom Baird as a partner. But the gamble paid off. The novelty of night baseball allowed the Monarchs to play two and three games a day and made them the most popular touring club in the nation.

Meanwhile, in Pittsburgh, former basketball star Cumberland Posey, Jr. had forged the Homestead Grays into one of the best teams in America. Posey, the son of one of Pittsburgh’s wealthiest Black businessmen, had joined the Grays, then a sandlot team, as an outfielder in 1911. By the early 1920s he owned the club and began recruiting top national players to supplement local talent. In 1925, he signed 39-year-old Smokey Joe Williams, and the following year he lured Oscar Charleston, whom many consider the top Black player of that era. Over the next several seasons Posey recruited Judy Johnson, Martin Dihigo, and Cool Papa Bell. In 1930, he added a catcher from the Pittsburgh sandlots named Josh Gibson, and in 1934 brought in first baseman Buck Leonard from North Carolina. Unwilling to subject himself to outside control, Posey preferred to remain free from league affiliations. Yet for two decades, the Homestead Grays reigned as one of the strongest teams in black baseball.

In the 1930s, Posey faced competition from crosstown rival Gus Greenlee, “Mr. Big” of Pittsburgh’s North Side numbers rackets. Greenlee took over the Pittsburgh Crawfords, a local team, in 1930. Greenlee spent $100,000 to build a new stadium, and wooed established ballplayers with lavish salary offers. In 1931, he landed the colorful Satchel Paige, the hottest young pitcher in the land, and the following year raided the Grays, outbidding Posey for the services of Charleston, Johnson, and Gibson. In 1934, James “Cool Papa” Bell jumped the St. Louis Stars and brought his legendary speed to the Crawfords. With five future Hall of Famers, Greenlee had assembled one of the great squads of baseball history.

The emergence of Gus Greenlee marked a new era for Black baseball, the reign of the numbers men. In an age of limited opportunities for Black people, many of the most talented northern Black entrepreneurs turned to gambling and other illegal operations for their livelihood. Novelist Richard Wright explained, “They would have been steel tycoons, Wall Street brokers, auto moguls, had they been white.” Like the political bosses of nineteenth century urban America, numbers operators provided an informal assistance network for needy patrons in the impoverished Black communities and represented a major source of capital for Black businesses. In city after city, the numbers barons, seeking an element of respectability or an outlet to shield gambling profits from the Internal Revenue Service or merely the thrill of sports ownership, came to dominate Black baseball. In Harlem, second-generation Cuban immigrant Alex Pompez, a powerful figure in the Dutch Schultz mob, ran the Cuban Stars, while Ed “Soldier Boy” Semler controlled the Black Yankees. Abe Manley of the Newark Eagles, Ed Bolden of the Philadelphia Stars, and Tom Wilson of the Baltimore Elite Giants all garnered their fortunes from the numbers game. Even Cum Posey, who had no connection with the rackets, had to bring in Homestead numbers banker Rufus “Sonnyman” Jackson as a partner and financier to stave off Greenlee’s challenge.

In 1933, Greenlee unified the franchises owned by the numbers kings into a rejuvenated Negro National League. Under his leadership, writes Donn Rogosin, “The Negro National League meetings were enclaves of the most powerful Black gangsters in the nation.” This “unholy alliance” sustained Black baseball in the Northeast through depression and war. Even the collapse of the Crawfords and demolition of Greenlee Stadium in 1939, failed to weaken the league which survived until the onset of integration. In 1937 a second circuit, the Negro American League was formed in the Midwest and South. Dominated by Wilkinson and the Kansas City Monarchs, the Negro American League relied less on numbers brokers, but more on white ownership for their financing.

The formation of the Negro American League encouraged the rejuvenation of an annual World Series, matching the champions of the two leagues. But the Negro League World Series never achieved the prominence of its white counterpart. The fact that league standings were often determined among teams playing uneven numbers of games diluted the notion of a champion.

Furthermore, impoverished urban Black people could not sustain attendance at a prolonged series. As a result, the Negro League World Series always took a back seat to the annual East-West All-Star Game played in Chicago. The East-West Game, originated by Greenlee in 1933, quickly emerged as the centerpiece of Black baseball. Fans chose the players in polls conducted by Black newspapers. By 1939, leading candidates received as many as 500,000 votes. Large crowds of Black and white fans watched the finest Negro League stars, and the revenues divided among the teams often spelled the difference between profit and loss at the season’s end.

By the 1930s and 1940s, Black baseball had become an integral part of Northern ghetto life. With hundreds of employees and millions of dollars in revenue, the Negro Leagues, as Donn Rogosin notes, “may rank among the highest achievements of black enterprise during segregation.” In addition, baseball provided an economic ripple effect, boosting business in hotels, cafes, restaurants and bars. In Kansas City and other towns, games became social events, as Black citizens, recalls manager Buck O’Neil, “wore their finery.” The Monarch Booster Club was a leading civic organization and the “Miss Monarch Bathing Beauty” pageant a popular event. Black baseball also represented a source of pride for the Black community. “The Monarchs was Kansas City’s team,” boasted bartender Jesse Fisher. “They made Kansas City the talk of the town all over the world.”

In several cities, white politicians routinely appeared at Opening Day games to curry favor with their often neglected Black constituents. When Greenlee Field launched its operations in Pittsburgh, the mayor, city council, and county commissioners lined the field boxes. Negro League owners also played a role in the fight against segregation. In Newark, Effa Manley, who ran the Eagles with her husband Abe, served as treasurer of the New Jersey NAACP and belonged to the Citizen’s League for Fair Play which fought for Black employment opportunities. Manley sponsored a “Stop Lynching” fundraiser at one Eagles home game.

The impact of the Negro Leagues, however, ranged beyond the communities whose names the teams bore. Throughout the age of Jim Crow baseball, even in those years when a substantial league structure existed, official league games accounted for a relatively small part of the Black baseball experience. Black teams would typically play over 200 games a year, only a third of which counted in the league standings. The vast majority of contests occurred on the “barnstorming” circuit, pitting Black athletes against a broad array of professional and semi-professional competition, white and Black, throughout the nation. In the pre-television era, traveling teams brought a higher level of baseball to fans in the towns and cities of America and allowed local talent to test their skills against the professionals. While some all-white teams, like the “House of David” also trod the barnstorming trail, itinerancy was the key to survival for Black squads. The capital needed to finance a Negro League team existed primarily in Northern cities, but the overwhelming majority of Black people lived in the South.

“The schedule was a rugged one,” recalled Roy Campanella of the Baltimore Elite Giants. “Rarely were we in the same city two days in a row. Mostly we played by day and traveled by night.” After the Monarchs introduced night baseball, teams played both day and night appearing in two and sometimes three different ballparks on the same day. Teams traveled in buses — “our home, dressing room, dining room, and hotel” — or sandwiched into touring cars. “We had little time to waste on the road,” states Quincy Trouppe, “so it was a rare treat when the cars would stop at times to let us stretch out and exercise for a few minutes.” Most major hotels barred Black guests, so even when the schedule allowed overnight stays, the athletes found themselves in less than comfortable accommodations. Large cities usually had better Black hotels where ballplayers, entertainers, and other members of the Black bourgeoisie congregated. On the road, however, Negro Leaguers more frequently were relegated to Jim Crow roadhouses, “continually under attack by bedbugs.”

The Black baseball experience extended beyond the confines of the United States and into Central America and the Caribbean. Negro Leaguers appeared regularly in the Cuban, Puerto Rican, Venezuelan, and Dominican winter leagues where they competed against Black and white Latin stars and major leaguers as well. Some Black players, like Willie Wells and Ray Dandridge, jumped permanently to the Mexican League, where several also became successful managers of interracial teams. As Wells explained, “I am not faced by the racial problem . . . I’ve found freedom and democracy here, something I never found in the United States . . . In Mexico, I am a man.”