There were 19 notable relievers traded in the days leading up to the July 31 Trade Deadline, with past and present All-Stars like Mark Melancon, Sergio Romo and Shane Greene among them. For the most part, it hasn't gone well. We took 18 of them and looked at their August stats, and so far, they've combined for a 5.35 ERA, an enormous jump from the 3.86 ERA they had through the end of July. Teams looking for relief generally haven't found it.

You'll notice we only included 18 of the 19, and the name we left out is one you likely aren't familiar with. You absolutely did not know Nick Anderson when the Twins signed him as an undrafted free agent in 2015, and you probably did not notice when they dealt him to Miami last November for a Minor League third baseman to avoid a 40-man roster crunch. (It's OK: Neither did we. Anderson didn't even rate a mention in the headline. The Minor League third baseman, Brian Schales, is hitting .189/.301/.378 in the Twins' system.)

It's even OK if Anderson didn't make your radar when he was with Miami, because the Marlins are in last place, Anderson wasn't their closer, and his 3.92 ERA made it easy to miss the strikeouts he was piling up. (Though we tried to tell you in April.) But now that he's with the Rays, who acquired him on July 31 in an intra-state deal that also sent Trevor Richards to Tampa Bay and Ryne Stanek and prospect Jesús Sánchez to Miami, he demands your attention. He's the best reliever traded at the Deadline. He might be one of the best relievers in the game, and if he'd been in the AL all year, he'd be running a quiet Rookie of the Year case.

This isn't just going to be about what he's done since Aug. 1, but since Anderson arrived in Tampa Bay, he has faced 26 hitters. We know it's overkill to list them all out, but ... just look at this insanity.

Double

Flyout to center field

Strikeout

Strikeout

Strikeout

Strikeout

Ground out to shortstop

Popout to first base

Strikeout

Strikeout

Strikeout

Strikeout

Groundout to shortstop

Strikeout

Strikeout

Strikeout

Strikeout

Strikeout

Strikeout

Strikeout

Strikeout

Strikeout

Flyout to center field

Single to center field

Single (infield, to shortstop)

Strikeout

That's 18 strikeouts, 0 walks, 3 hits, a stretch of nine consecutive strikeouts (snapped on Monday night) -- one behind Tom Seaver's 1970 record of 10, though Tom Terrific did do it in a single game -- and just about as close to perfection as you can get. It's the best month of the season; it's the best month of anyone's season. Anderson has a 69.2% strikeout rate as a Ray, which is the best of the over 43,000 months since 2002 where a pitcher faced at least 20 hitters. Second place: Craig Kimbrel's August 2012 63.6%. Third place: Josh Hader's 62.9% last April. It's a small sample, sure, but that's a list with two legends atop it.

Anderson has one save, no name value, and the second-highest seasonal strikeout rate (41.0%) in baseball behind only Hader. Let's get nuts: It's one of the 25 best strikeout seasons of all time. So: Who is this guy, what makes him so dominant, and how in the world did he escape any prospect list notice at all on his way up?

It's not just about the numbers, after all. It's about a potentially big role in the postseason, given that the Rays currently hold the second Wild Card spot and still have a shot to host the game at Tropicana Field ... possibly against the same Minnesota team that cut Anderson loose less than a year ago, and wouldn't that be fun?

In one sense, Anderson makes it easy, because he throws only two pitches: a four-seam fastball, and a breaking pitch that we're going to call a curveball. (Some sites classify the breaking pitch as a slider, but Anderson himself has clarified that it's a curve. The truth is that it's something in between, as we'll get to.)

“The fastball/breaking ball mix and the fastball play big,” Rays general manager Erik Neander told MLB.com after the deal. “High end, elite-level strikeouts, keeps his walks down, and we look forward to having him in our big league bullpen. We believe this is someone that can make a big impact for us, not just for this year, but for years to come.”

That word there -- mix -- is a big part of this, and we'll need to investigate each pitch to explain.

The four-seam fastball is a good pitch, though it's not by itself a truly elite one. It's fast, sure, but 96.0 mph is 90th percentile, meaning 10 percent of pitchers throw harder fastballs. The spin is above-average but not elite, in the 65th percentile.

What he does have, however, is a huge amount of rise. Pitch movement is primarily based around the amount of spin combined with the direction of spin, and Anderson's spin direction is such that nearly 94% of it contributes to movement, a well above-average number. Take good spin, add in outstanding spin direction, and you get truly elite rise:

Most four-seam rise above average, 2019 (min. 300 four-seamers)

+4.3 inches above average, Colin Poche, TB

+4.0 inches above average, Sean Doolittle, WSN

+3.5 inches above average, Anderson, TB

+3.2 inches above average, Hunter Wood, CLE

+3.1 inches above average, Emilio Pagán, TB

(You think the Rays have a type? Wood spent parts of the least three seasons in Tampa Bay before being traded on July 28. Poche and Pagán have each been acquired since the start of 2018.)

What that means is that the average four-seamer at Anderson's velocity and release drops 13.8 inches from the mound to the plate, but his drops only 10.4 inches. That gap of 3.5 inches is the rise, the difference from what a hitter expects to see, and it's how he gets batters to consistently swing under the ball, like former teammate Harold Ramirez did:

That said, the outcomes are just OK. His swing-and-miss rate of 26.0% is only somewhat better than the Major League average of 21.6%, and the .279 average and .459 slugging allowed are each worse than Major League average (.270 and .490). It's a strong pitch, and a necessary one, but as we investigated with Hader, when batters can make contact, they make very good contact.

It's not, however, his curveball ... or slider ... or splitter ... or whatever that is. He calls it the curve, so we do too, but it's not really a traditional curve, because it's thrown much harder (83 mph, where league average is 78.9 mph) and it has seven inches less drop than an average curve at his velocity does. What it does appear to do is go straight up-and-down -- it has just one inch of horizontal break -- and because it's neither a true curve nor a real slider, it appears to be a pitch unto itself.

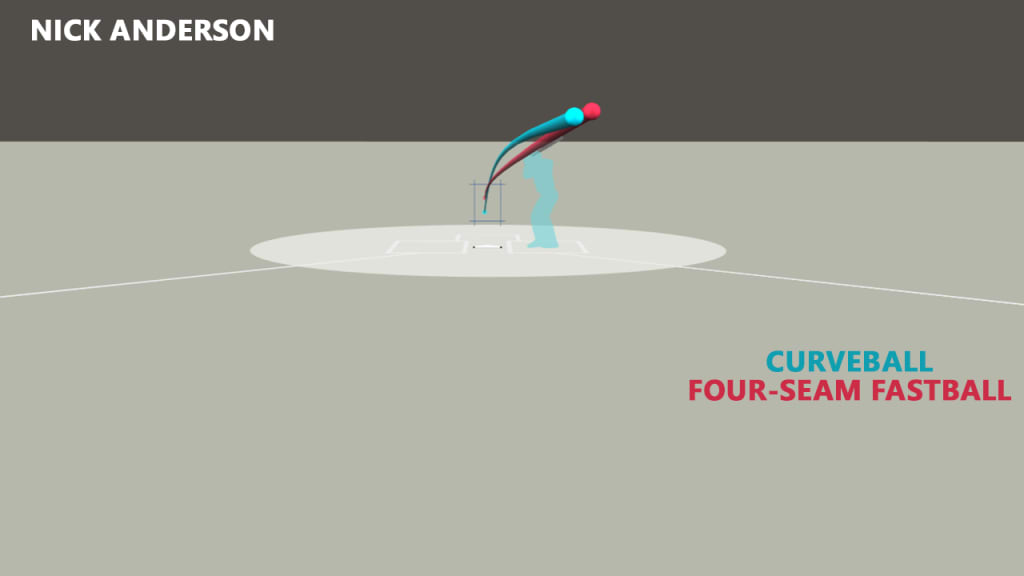

But it really also appears to be about how the pitches work off one another. When Anderson releases them, they come out of nearly the exact same spot ...

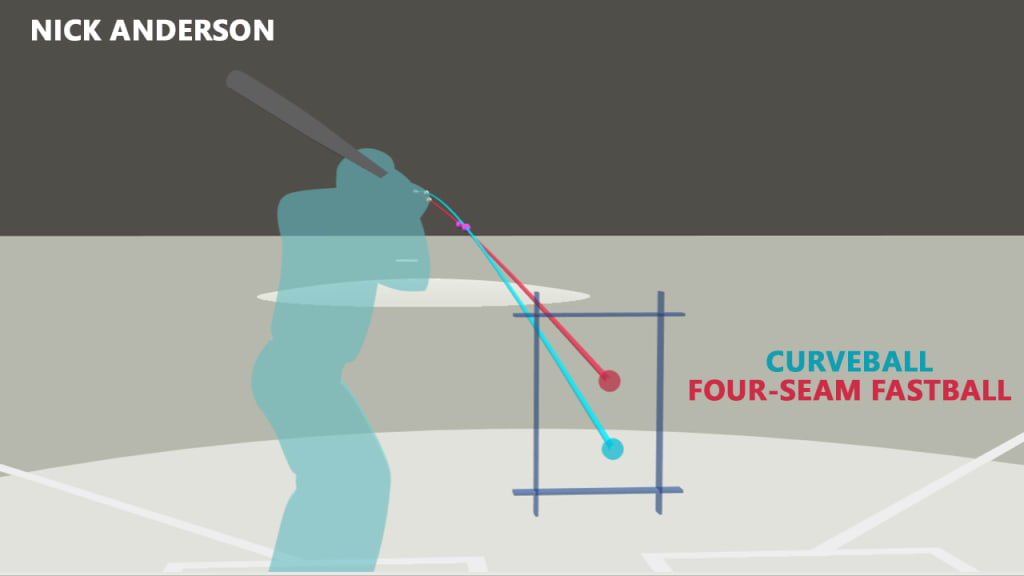

... and when they get to where the batter has to make a swing-or-don't decision -- the final one-sixth of a second, indicated by the pink dots on the below image -- they still look very similar ... right up until they don't.

There's also some indication that the direction of the spin on the two pitches mirrors one another so well that it's another way to make it difficult for the batter to know which is coming, though we're still in the early stages of being able to truly quantify that.

But what changed in Tampa Bay? He was good in Miami; he's been unhittable in Tampa Bay.

His velocity is up slightly, about half a tick from Miami. That's nice, but that's not it. It might be a lot about pitch usage -- as a Marlin, he threw a fastball on the first pitch 43% of the time. As a Ray, that's up to 82% of the time. At the risk of being too predictable, he was ahead in the count only 35% of the time with the Marlins, which is up to 51% with the Rays. Once he got ahead in the count with Miami, he allowed a .177 average; with the Rays, it's just .095.

This is not to say that Anderson is baseball's next great closer, because the track record of two-pitch guys hitting it big in their age-28 season and maintaining that for many years is not strong. It's not to say that the Marlins made a mistake, because they turned a no-risk November pickup into a good pitcher in Stanek and a good prospect in Sánchez. And it's not even to say that there's no risk factor in 2019, because when we dug into Hader's bizarre combination of strikeouts and allowing hard-hit contact, you'll notice Anderson was on that chart, too (though he's fixing that somewhat by allowing more hard-hit contact on the ground):

It's just to say that Anderson wasn't at all the first or third or sixth biggest name dealt on July 31, but so far, he clearly looks like the best reliever moved. He looks like one of the best relievers in the game. After nearly losing his chance due to legal problems and several years in independent ball, Anderson has arrived in a way no one would have expected.

"Nick Anderson, the more we dug into it, the more we thought that there was high-end, back-end potential,” Neander said.

He's not wrong. Anderson has one save, but it doesn't matter. He's elite. You might be seeing what Neander means in the AL Wild Card Game.