LOS ANGELES -- The history of Japanese involvement in baseball is both longstanding and rich. Nowhere is that more evident than at “Baseball’s Bridge to the Pacific: Celebrating the Legacy of Japanese American Baseball,” an exhibit currently showing in Dodger Stadium’s Left Field Pavilion.

The exhibit, which opened at the ballpark in advance of the Dodgers’ Japanese Heritage Night on June 15, was available for viewing during All-Star Week 2022 and will continue to be through the remainder of the season, including the playoffs. It is sponsored by the Nisei Baseball Research Project, the Arizona Baseball Legacy and Experience and the Japanese American Citizens League, Arizona Chapter.

“We're very honored to be here to share with fans all this hidden legacy and history of these marginalized, invisible and forgotten ballplayers, is what I call them,” said Kerry Yo Nakagawa, director of the NBRP and the exhibit’s founding curator.

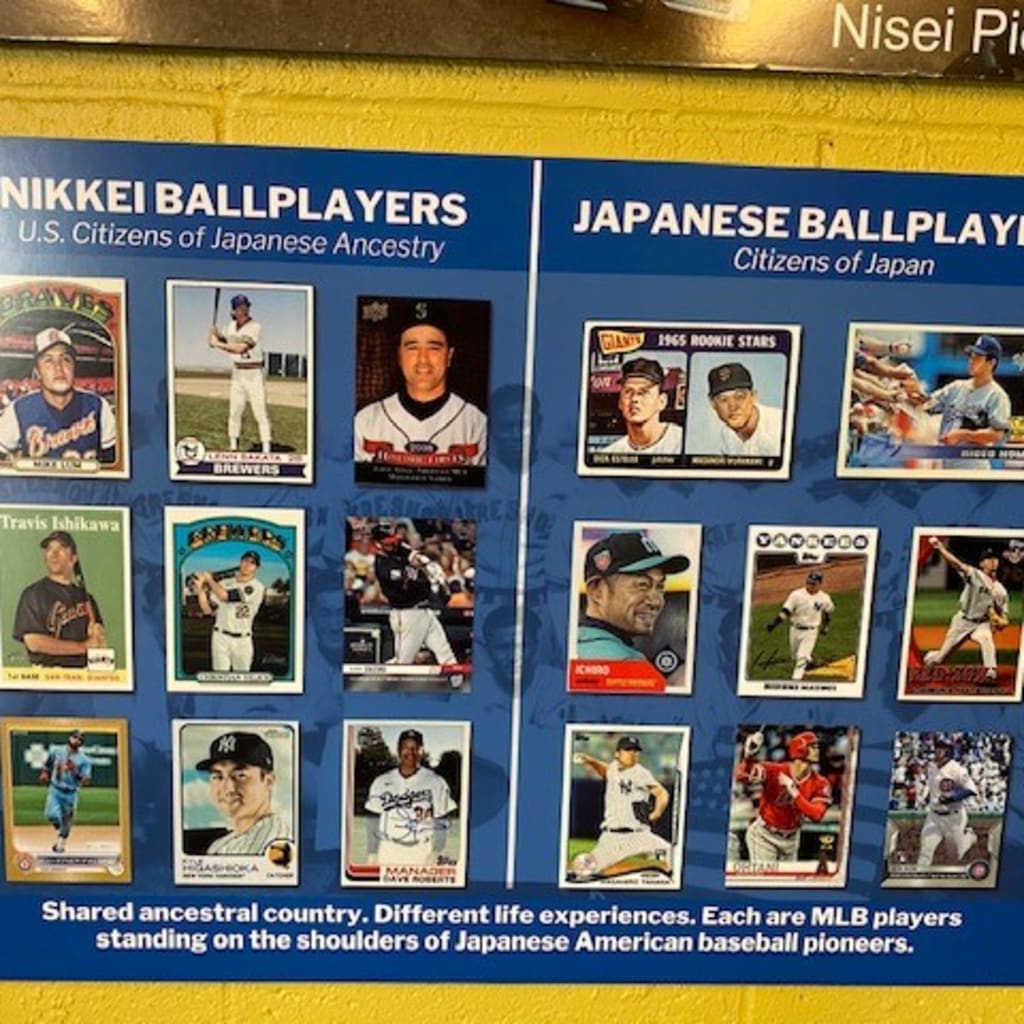

From Hideo Nomo to Ichiro Suzuki to Shohei Ohtani, it’s hard to imagine modern Major League Baseball without the impact of Japanese talent. But it’s also important to remember the pioneers who paved the way for them -- those who never got the chance to play at the game’s highest level due to racial discrimination.

“We had great Major League [caliber] players that were denied,” said Nakagawa. “So that's why today, we look at all the Asian players in Major League Baseball, [those are] their ancestral godfathers. For us, Ohtani is standing on their shoulders. Ichiro is standing on these guys’ shoulders.”

“Baseball’s Bridge” introduces visitors to those forebearers as it walks them through the relationship between Japan and baseball, which dates back 150 years. As baseball grew in popularity in Japan, so too did it grow in popularity amongst Japanese American citizens (“Nikkei”). The first Japanese American baseball team formed in Hawaii in 1899, while the first Japanese American team on the U.S. mainland formed in San Francisco in 1903.

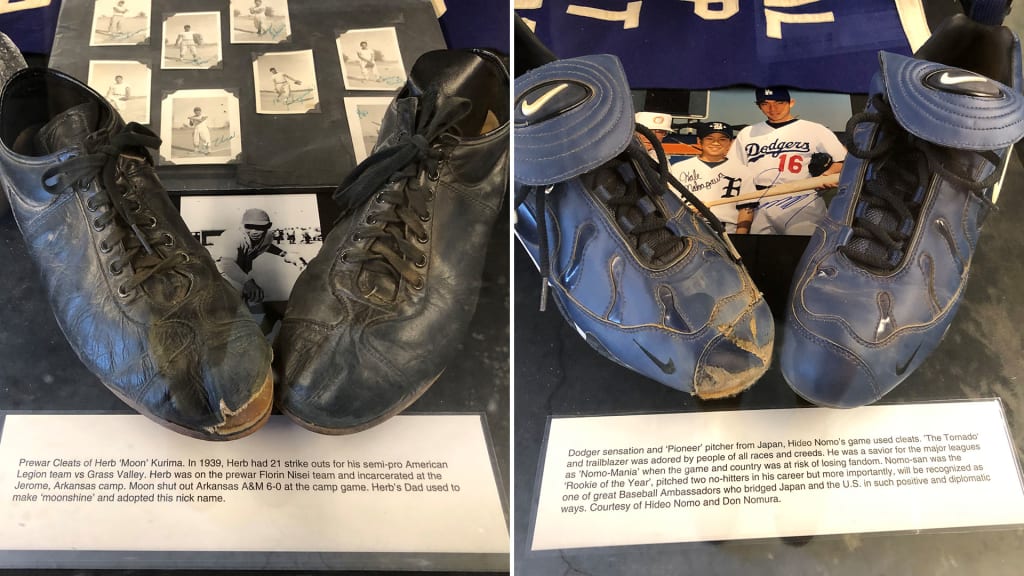

The exhibit features historical panels, trivia questions with answers obtainable via QR code, and a vast array of artifacts that spans more than a century. There’s a set of cleats worn by Herb “Moon” Kurima -- a right-handed pitcher who once struck out 21 batters in a semipro game in 1939 -- juxtaposed with a pair of cleats worn by Nomo in the 1990’s.

“They still wear out the right toe, no matter how much technology there is,” said Nakagawa.

More sobering is the wooden home plate dug out of Zenimura Field, located at the Gila River Interment Camp in Butte, Ariz. In one of the gravest acts of injustice committed on American soil, Japanese American life was upended by World War II and Executive Order 9066, issued by President Franklin Roosevelt on Feb. 19, 1942. The order led to the unjustified incarceration of Japanese American citizens in internment camps, located mostly in the western United States and as far east as Arkansas.

Baseball was a popular form of recreation in these centers, with teams from different camps even being allowed to travel to play each other.

“It was demeaning and humiliating to be incarcerated in your own country,” reads a quote on a plaque from George Omachi, a one-time internee in Jerome, Ark., who went on to be a Major League scout. “Without baseball, camp life would have been miserable.”

Several of the 10 internment camps have remained preserved as historical sites, including Manzanar, which is about a four-hour drive northeast from Dodger Stadium in California’s Owens Valley. The baseball field there still stands somewhat intact.

Although baseball was used as a tool for diplomacy in postwar Japan, it took quite a while for either Japanese or Nikkei players to form any real foothold in MLB. There was a nearly 30-year gap between when the first Japanese-born player crossed over from Japan’s Nippon Professional Baseball league to MLB -- left-hander reliever Masanori Murakami, who debuted for the Giants in 1964 -- and when the second did, which was Nomo with the Dodgers in ‘95. The first Japanese American player to reach the Majors was outfielder/first baseman Mike Lum, who debuted with the Braves in 1967.

The numbers of both Japanese-born and Nikkei Major Leaguers have significantly increased in the past couple of decades, each totaling in the dozens. There have even been two MLB managers of Asian descent, including Dodgers manager Dave Roberts, who was born in Japan to a Japanese mother and an African American father.

“Baseball’s Bridge,” which has been housed in several places -- including a six-month stint at the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1998 -- will continue to travel once it’s done at Dodger Stadium. It might go to Angel Stadium at some point in the future, and the hope is that it might go to other ballparks as well, particularly those with legacy Japanese players. Eventually, the goal is to find a permanent home for the exhibit, possibly in Cooperstown or at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.

“We’re so appreciative that the Dodgers have kind of re-given it life to expose Major League Baseball fans that probably never knew about our history,” said Nakagawa.