There is no place quite like the Plaque Gallery at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y. It’s easy to lose yourself in the 3,660-square-foot centerpiece to the museum that tells a history of the game, highlighting accomplishments one by one for the almost 350 members enshrined. Nearly every important moment in baseball history pours through the walls as one walks through this carefully curated and manicured display.

It is curious then that for over 40 years Jackie Robinson’s plaque had no mention whatsoever of his place in baseball history -- in American history -- for breaking the color barrier in 1947. It is an achievement so well-known and woven into the fabric of the game that we celebrate its importance every April 15 on the anniversary of Robinson’s Major League debut.

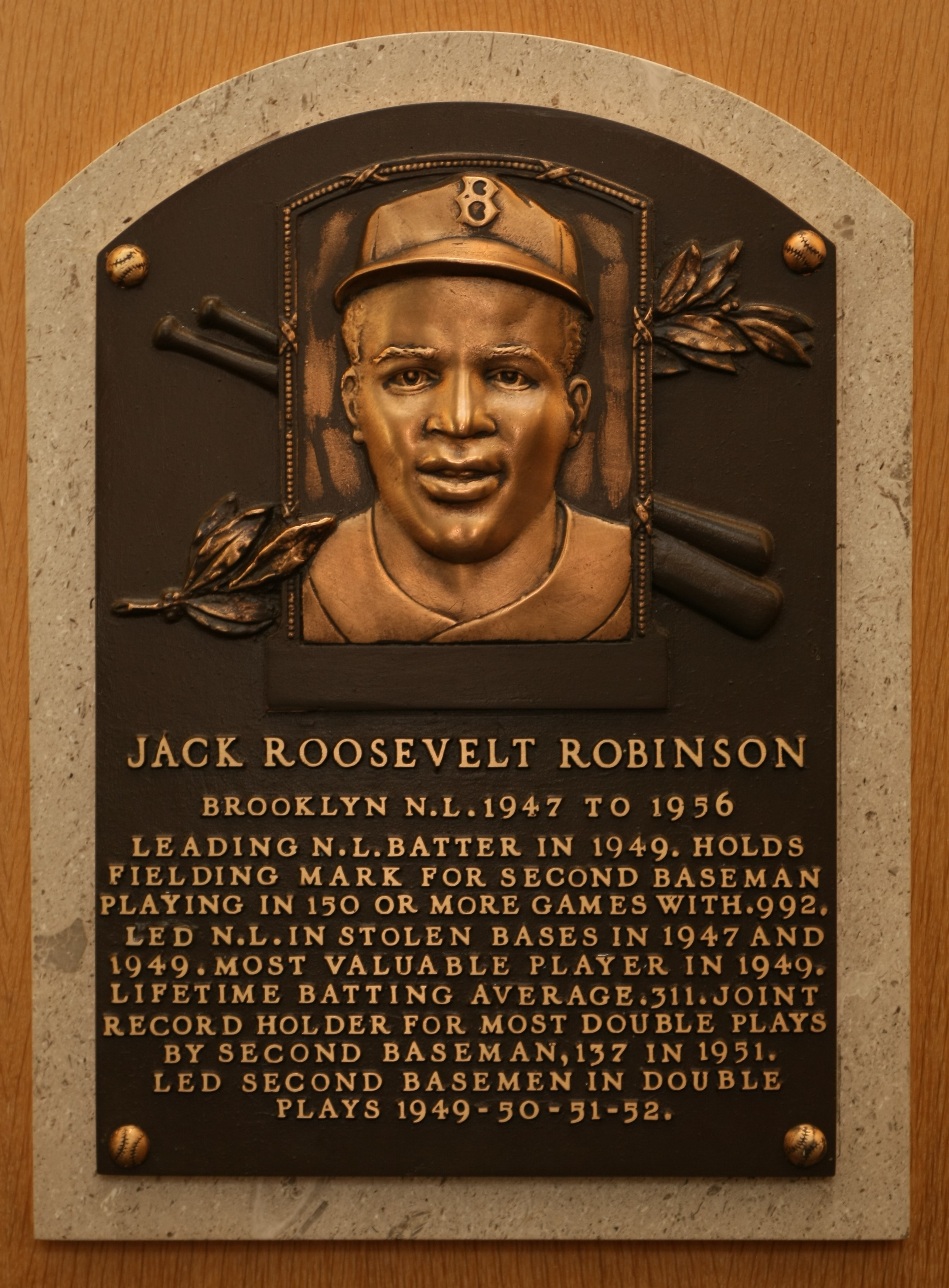

All of that was entirely left out of the plaque that was unveiled on July 23, 1962, the day Robinson was inducted into the Hall of Fame. Here is the original text:

JACK ROOSEVELT ROBINSON

BROOKLYN N.L. 1947 TO 1956

LEADING N.L. BATTER IN 1949. HOLDS

FIELDING MARK FOR SECOND BASEMAN

PLAYING IN 150 OR MORE GAMES WITH .992.

LED N.L. IN STOLEN BASES IN 1947 AND

1949. MOST VALUABLE PLAYER IN 1949.

LIFETIME BATTING AVERAGE .311. JOINT

RECORD HOLDER FOR MOST DOUBLE PLAYS

BY SECOND BASEMAN, 137 IN 1951.

LED SECOND BASEMEN IN DOUBLE

PLAYS 1949 - 50 - 51 - 52.

This is hardly the description one would expect to find on a marker for all time dedicated to a man who changed the face of American sports the way Robinson did. So how did it come to be that visitors who made their way to Robinson’s plaque, arguably one of the most frequented spots in the museum, found themselves staring at such plain words to describe a career so extraordinary?

It actually began with Robinson’s own wishes.

“I hope that I will be judged on my ball playing ability alone, not on the fact that I broke the color line,” Robinson told New York Daily News columnist Dick Young before the 1962 BBWAA Hall of Fame election, which marked his first appearance on the ballot.

Robinson later amended the comment to say that he felt his historical significance should not be “the primary consideration,” while acknowledging that the wave of change he ushered in had to at least be a factor. Perhaps Robinson was also keenly aware that some voters could be swayed against casting a ballot with his name for the very same reason.

The Dodgers career on which Robinson wished to be judged lasted only 10 seasons, yet the accomplishments were quite lofty, as he was a key member of six pennant winners and one World Series champion team.

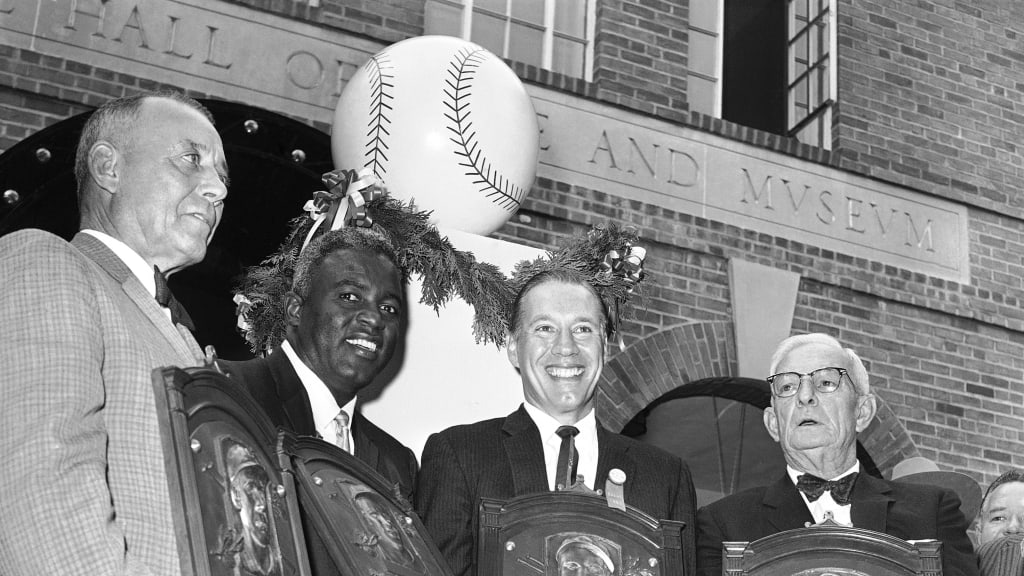

It is impossible to know if the individual voters used Robinson’s wishes as their personal guidelines. However, 77.5 percent of them (124 out of 160) did indeed check off Jackie’s name to make him a first-ballot Hall of Famer.

“I don’t think the writers chose Jackie in spite of his color or because of it,” Branch Rickey, the Dodgers general manager who signed Robinson, said upon learning of the election in January 1962. “They chose him on merit.”

Former Dodgers teammate Pee Wee Reese knew of Robinson’s edict to the voters, but he echoed Rickey’s sentiment.

“I don’t think that would even enter the mind of anyone who saw Jack do as much on the baseball field as I did,” Reese said.

With Robinson’s wishes for the election process in mind, the inscription on his plaque followed suit. While everyone across the land recognized the colossal impact he made not just to baseball but to the rest of the sporting world and American society at large, none of this was captured on the plaque that would hang in Cooperstown.

Inside the museum, the plainness of language and lack of more career details wasn’t entirely unique to Robinson’s plaque. For example, Babe Ruth’s plaque lauds him as the “greatest drawing card in history of baseball,” but then almost glosses over his astonishing statistics by calling him the “holder of many home run and other batting records” and stating that he “gathered” 714 home runs.

Through the years, as more players became inducted, the plaques and the language on them started to evolve. In addition to more detailed statistics that told deeper stories of players’ careers, they began to include colorful nicknames like “The Sandman” for Mariano Rivera and “The Hawk” for Andre Dawson.

And in 1998, Larry Doby, who joined Cleveland of the American League less than three months after Robinson debuted with Brooklyn, was elected to Cooperstown. The final words of the first sentence on his Hall of Fame plaque celebrate Doby for “integrating the American League in 1947.”

It was sometime after Doby’s induction that discussions about changing the wording on Robinson’s plaque began. For several decades, staffers at the Hall of Fame had found themselves routinely being asked about the glaring omission. It was, after all, one of the main attractions in the gallery given his stature and popularity.

“Parents trying to explain to their children what Jackie Robinson’s role was as a player and as a human being weren’t able to do that looking at his plaque,” explained Jeff Idelson, former President of the Hall of Fame. “The plaques are a historical representation of a moment in time when they are written. The only time they really get changed are for factual errors. But in terms of changing a plaque, that was highly unusual.”

These were indeed unusual circumstances, and nearly every visitor to Cooperstown knew it. In the end it was Rachel Robinson, Jackie’s widow, who seemed to know that the time was right to update the historical record on the plaque despite her husband’s wishes four decades earlier.

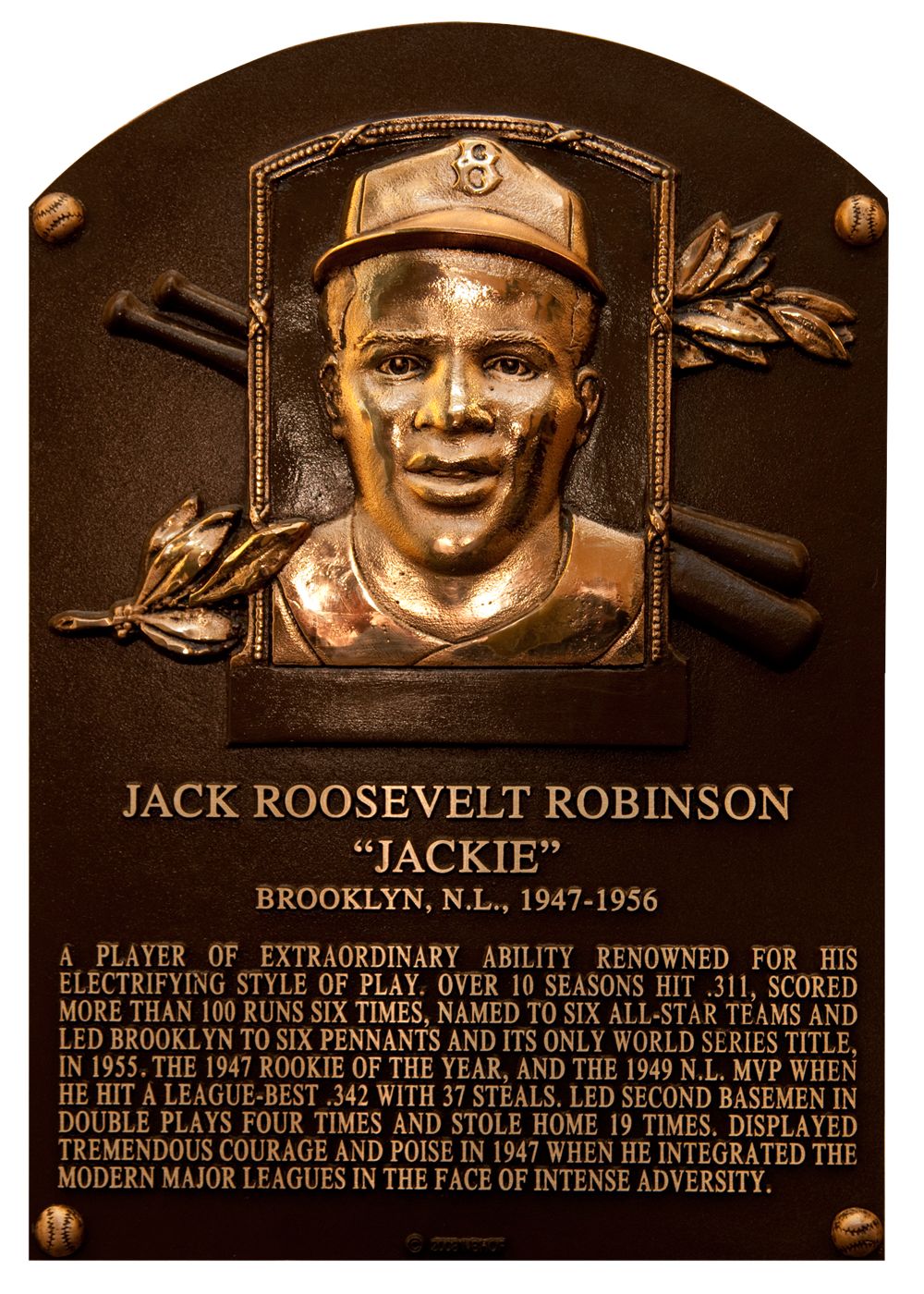

Rachel contacted former Cincinnati Reds great Joe Morgan -- a Robinson family friend, Hall of Famer, and the Hall’s Vice Chairman of the Board -- and the wheels were put in motion. The inscription was carefully chosen, and in June 2008, a new plaque was unveiled inside the Plaque Gallery. Here is how it reads:

JACK ROOSEVELT ROBINSON

“JACKIE”

BROOKLYN, N.L., 1947-1956

A PLAYER OF EXTRAORDINARY ABILITY RENOWNED FOR HIS ELECTRIFYING STYLE OF PLAY. OVER 10 SEASONS HIT .311, SCORED MORE THAN 100 RUNS SIX TIMES, NAMED TO SIX ALL-STAR TEAMS AND LED BROOKLYN TO SIX PENNANTS AND ITS ONLY WORLD SERIES TITLE IN 1955. THE 1947 ROOKIE OF THE YEAR, AND THE 1949 N.L. MVP WHEN HE HIT A LEAGUE-BEST .342 WITH 37 STEALS. LED SECOND BASEMEN IN DOUBLE PLAYS FOUR TIMES AND STOLE HOME 19 TIMES. DISPLAYED TREMENDOUS COURAGE AND POISE IN 1947 WHEN HE INTEGRATED THE MODERN MAJOR LEAGUES IN THE FACE OF INTENSE ADVERSITY.

From the inclusion of “Jackie” under his full name to the stronger opening line to the specifics of his prowess in stealing bases, this inscription dug much deeper into Robinson's outstanding career. The last sentence -- which at last described Robinson’s proper historical impact -- was purposefully placed at the end “as a way to honor Jackie’s wishes for how and why he was inducted into the Hall of Fame,” according to Idelson.

"There is no person more central or more important to the history of baseball for his pioneering ways,” Hall of Fame Chairman of the Board Jane Forbes Clark said in 2008. “His impact on our game is not fully defined without the mention of his extreme courage."

"A very important part of Jack's life has been acknowledged today in a more total way," Rachel Robinson said when the plaque was shown to the public for the first time. “As he said … those of us who are fortunate to receive such an honor must use it to help others. As young people view Jack's new Hall of Fame plaque, they will look beyond statistics and embrace all that Jack has meant and all that they can be.”

Rachel went on to explain that while Jackie’s initial desires were noble, he would accept and appreciate the change so that his most vital contribution to the game could be recognized in this manner.

"I think he would understand now that we need to go beyond that and we need to think in terms of social change in America," she said. "He would want a part in that. I don't think he would object."

The original plaque that hung in Cooperstown from 1962 to 2008 still has a place for those who want to see it. It is on loan and displayed at the Jackie Robinson Museum in New York City.