The crazy story behind MLB’s last forfeit

[Note: A version of this story originally ran on MLB.com in August 2019.]

It was sometime around 3 a.m. ET when the phone rang in Leonard Coleman’s hilltop home in New Jersey, rousting the National League president from his slumber.

“Mr. Coleman, it’s Jim Quick,” the voice on the other end of the line announced, “and Bob Davidson’s on the line, too.”

Groggy, confused, and quite possibly convinced this must all be a strange dream, a hoarse Coleman asked what was the matter. Why were these two umpires calling him from their Pasadena, Calif., hotel in the middle of this mid-August night in 1995?

“Well,” Quick explained, “we had to forfeit a game at Dodger Stadium.”

Now Coleman was awake.

“You WHAT?!”

* * * * *

Baseball’s long history is filled with forfeitures. In its earliest, crudest days, they were almost as much a part of the game as tiny gloves, funny mustaches and Old Hoss Radbourn victories.

According to the data at Retrosheet.org, from 1871-99, there were an average of 3.4 forfeits per year, with 13 in the ’84 season alone. The best-of-seven ’85 “World’s Championship” to decide a National League winner between the Chicago White Stockings and St. Louis Browns technically ended in a 3-3-1 deadlock because Browns manager Charles Comiskey called his team off the field to protest a ruling in Game 2.

The pace of abandoned games began to slow considerably in the 20th century, from two per year in the 1900s to one every two years in the 1910s, with a steady downward dip from there. The 1960s were the first decade to be forfeit-free.

Well, we had to forfeit a game at Dodger Stadium.

Jim Quick

Things did perk up in the unmistakably odd 1970s, which featured the two most infamous forfeits of all: Ten-Cent Beer Night at Cleveland Municipal Stadium in ’74, and Disco Demolition Night at Comiskey Park in ’79. But in the 40 years since that latter bit of vinyl violence, baseball has had only one game called on account of forfeit. It’s a game that came dangerously close to having major pennant race repercussions and one that, 24 years after it was rendered completely incomplete, still sparks disagreement over who to blame.

It happened on Aug. 10, 1995, the night the Dodgers forfeited a home game vs. the Cardinals because of souvenir balls.

* * * * *

As is often the case with tales of baseball bickering, this one begins with an umpire’s strike zone.

Quick was the home-plate umpire and crew chief that night, and it was one of those games in which every pitch felt pivotally important. The game was close, and so was the NL West pennant race, with the Dodgers just a game behind the first-place Rockies.

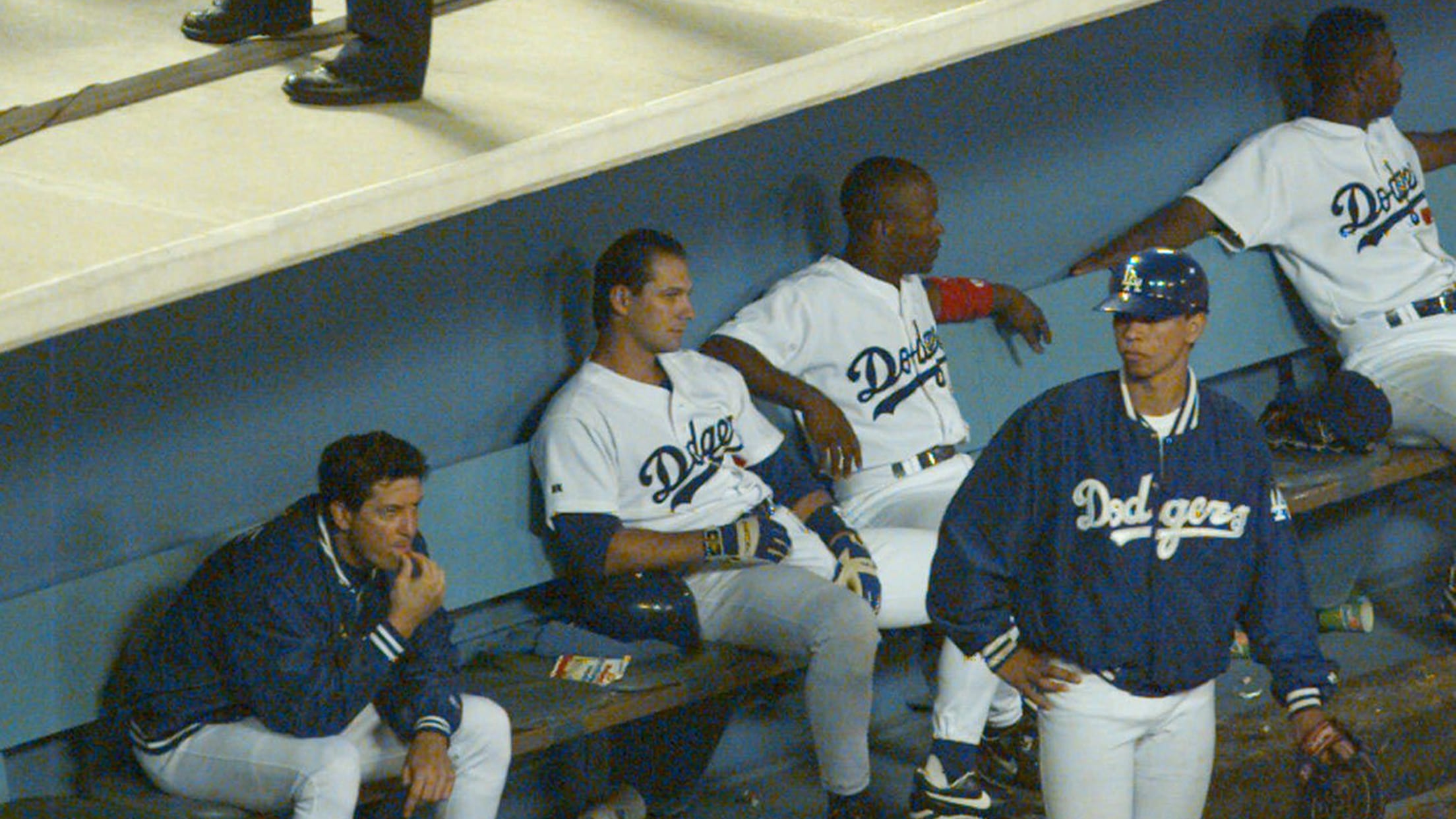

It was also the height of “Nomomania.” Hideo Nomo made the 19th start of a sensational rookie season that would earn him the NL Rookie of the Year Award. A crowd of 53,361 had packed Dodger Stadium both to see Nomo -- who allowed only two runs in eight sharp innings of work -- and to receive a souvenir ball commemorating L.A.’s many previous winners of the rookie honor.

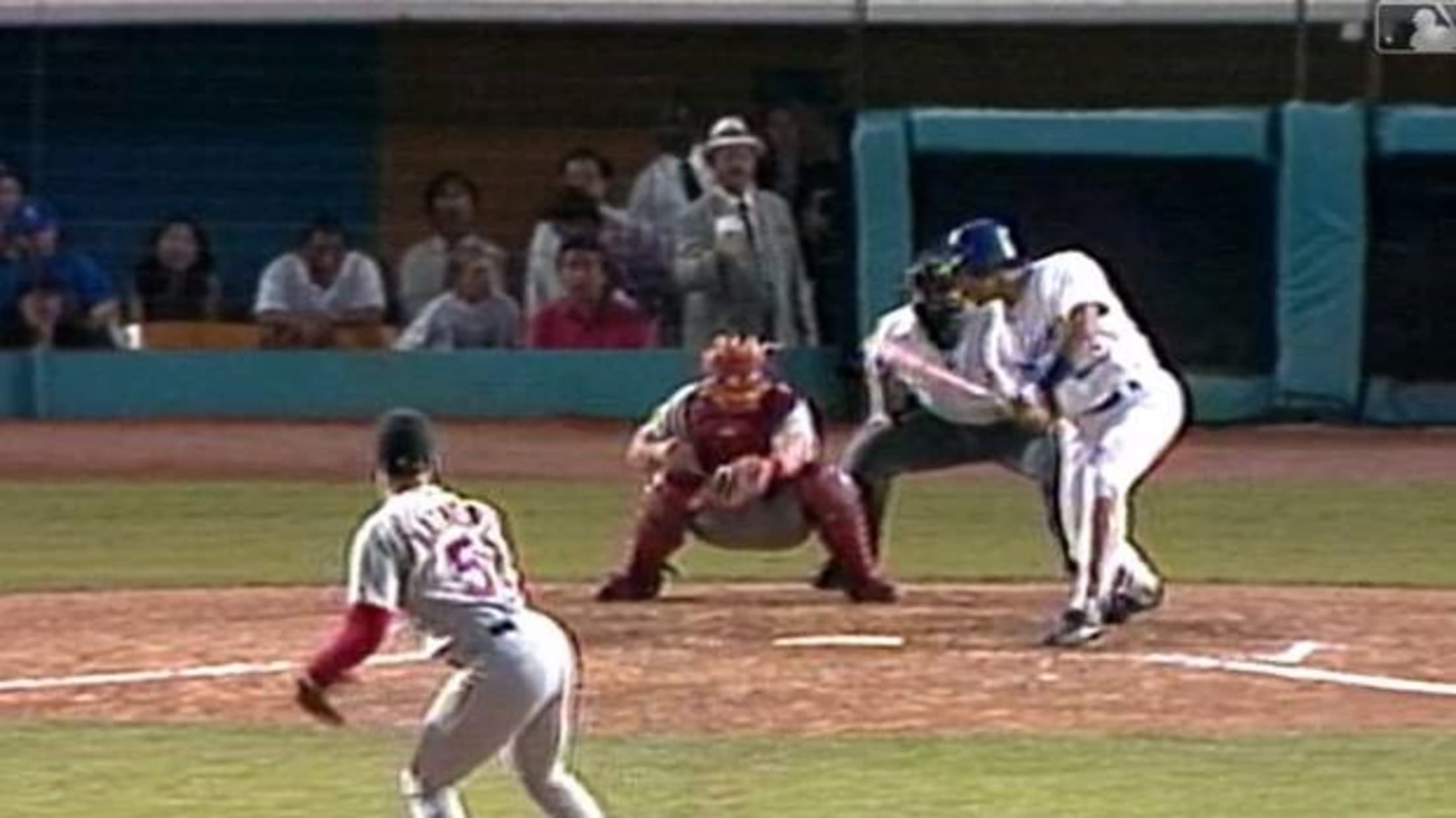

Coincidentally, it was one of those former Rookies of the Year -- 1992 winner Eric Karros -- at the plate in the bottom of the eighth, with the Dodgers trailing 2-1 and desperately trying to get Nomo some run support. There were two runners aboard with two outs, when Karros checked his swing on a 1-2 fastball from Cardinals reliever T.J. Mathews that may or may not have caught the outside corner.

Quick rung him up.

“Quick was [bleep] behind the plate,” Karros says all these years later, “just having a bad night.”

In the heat of the moment, Karros let Quick know his feelings about the strike call. Sure enough, he was ejected for the outburst.

The event contributed to a certain energy in the ballpark heading into the final frame. In addition, a number of unruly fans -- for reasons that have been lost to history (or possibly just involved alcohol) -- had already flung their souvenir balls onto the field in the seventh inning, causing a brief delay.

The bottom of the ninth commenced with the Dodgers and their fans still fuming over Quick’s strike zone, and the umpiring crew concerned about the potential for further, um, fan engagement.

• Box score, STL-LAD, Aug. 10, 1995

John Mabry, who was playing right field for the Cardinals, remembers what can best be described as a warning shot fired by a fan just before the half inning began.

“Somebody threw a ball into the outfield at the start of the inning,” he said. “I picked it up and acted like I was going to throw it into the crowd, but I deked them and threw it into the bullpen. They got mad and threw another one in. Then they threw another one at [center fielder] Brian Jordan. He looked at me and shrugged his shoulders.”

* * * * *

With the score still 2-1 and the Dodgers up in their last chance against Cards closer Tom Henke, Raul Mondesi led off. He worked the count 3-0, then took a pitch at or just below the knees.

“I lived on the edges,” Henke says. “That’s how I made my living, especially toward the end of my career like that. I couldn’t live in the middle of the plate, or those guys would have killed me.”

Mondesi, thinking he had ball four, was on his way to first base when Quick called it a strike.

An already tense crowd grew more agitated.

I lived on the edges. That’s how I made my living, especially toward the end of my career like that. I couldn’t live in the middle of the plate, or those guys would have killed me.

Tom Henke

The next pitch wasn’t on the edge and wasn’t a strike. It was well outside (you can see for yourself in this YouTube clip of the ESPN “SportsCenter” broadcast).

Quick called it strike two.

Now the Dodgers crowd was really boiling, as was Mondesi. And when Henke threw him an almost identical offering outside the zone in a 3-2 count, Mondesi had no choice but to swing. His big whiff made for a big first out of the inning.

Mondesi was the next to let Quick know what he felt about his strike zone, and he, like Karros, got thrown out of the game.

(Quick, who retired in 1998, did not respond to an interview request sent through the MLB Umpires Association. Mondesi, recently sentenced to eight years in a Dominican Republic prison on corruption charges, could not be reached for comment.)

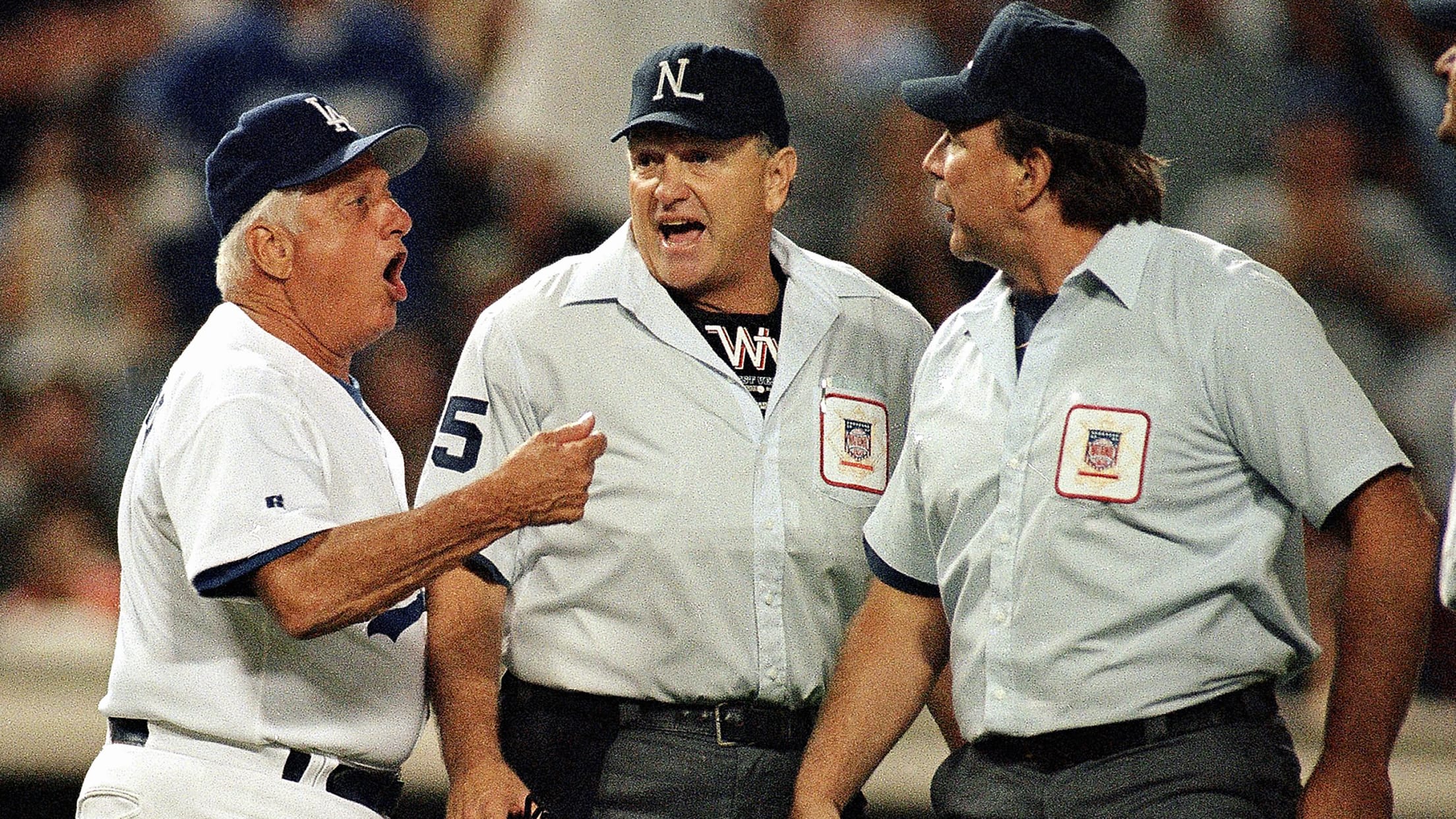

Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda joined the fray, and he got thrown out, too.

In the aftermath of the evening, Davidson told the large group of reporters gathered outside the umpires’ room that Lasorda’s typically ardent, arm-flapping argument style was what whipped the crowd into a frenzy.

“In my opinion, Lasorda instigated the whole thing,” Davidson had said. “I would put the full blame on him and management for giving baseballs away before the game.”

Though he got an earful from the league office for publicly voicing that opinion at the time, Davidson stands by that assertion today (even if he did enjoy arguing with Tommy from time to time).

Then-Dodgers general manager Fred Claire disagrees.

“Tommy’s Tommy,” Claire said of the celebrated manager, who passed away in January 2021. “He didn’t bump the umpire or anything. He manages with passion. That [argument] wasn’t any different than Tommy disputing any other near-play or call he didn’t agree with. It’s not as if a very mild manager went crazy.”

What is not disputed is what came next: the baseballs.

“They came raining down from the upper deck,” Mabry recalls. “And the next thing to come was the bottle of Jack [Daniels] that hit me.”

Says Davidson: “I think I remember reading they gave out 35,000 baseballs that day. And I think pretty much all of them were on the field! I don’t think too many fans brought them home.”

The players were called off the field. Mark Sweeney, then a rookie first baseman on the Cards, remembers watching from the dugout as the balls kept landing.

They came raining down from the upper deck. And the next thing to come was the bottle of Jack [Daniels] that hit me.

John Mabry

“The grounds crew was picking up the balls with empty buckets,” he says. “They must have filled about 15-20 buckets.”

Here’s where there is more disagreement: On the night of the forfeit, Claire complained to reporters that no public-address announcement was made to warn fans about the potential forfeit should they continue to throw balls on the field. In the present day, Davidson believes at least one announcement was made prior to the ninth. Mabry and Henke both remember an announcement in the ninth.

“It would have been a different story if they hadn’t been warned,” Henke says.

Whatever the case, the players had now been removed from the field twice. Once the cleaning process was complete, the Cardinals players returned to the field to resume the ninth with one out.

Then, per the Los Angeles Times report from that night, another ball was heaved from the bleachers.

In Quick’s judgment, that was enough. Three strikes and you’re out. Davidson was the one who waved his hands to make it official, with the forfeit -- and, therefore, the loss -- going to the home team.

“[Quick] told me, ‘Wave it off, we’re done,’” Davidson says. “It was the right move to make.”

* * * * *

All these years later, some think the merits of the decision are still up for debate.

“I understand it only takes one ball to cause an injury,” says longtime Dodgers broadcaster Rick Monday, “but I thought another announcement may have been a better way to at least attempt to get the game continued.”

Says Claire: “I’ve seen many disputes, many delays, many things taking place on the field. But all at once, in a close ballgame, when you’re fighting for the pennant and first place, you’ve lost because an umpire made a ruling. I didn’t like it then, I don’t like it now, and I won’t like it 30 years from now.”

The Cardinals sure loved it. Heck, this was the only game they won on a nine-game road trip.

All stats count in a forfeit. So Henke, who retired after that season with the fifth-highest career save total at the time (311), remembers feeling like he got a freebie, especially with the Dodgers in the middle of their order.

“As I walked in the dugout, I was thinking, ‘Hey, that was all right,’” he says. “‘I get a save and don’t have to do anything!’”

As I walked in the dugout, I was thinking, ‘Hey, that was all right.' I get a save and don’t have to do anything!’

Tom Henke

It was the first forfeit in the NL in 41 years and the last in either league since. The Dodgers obviously voiced their concerns to the league office, but once Coleman had snapped back to life and assessed the situation, he deemed that the Dodger Stadium crowd had caused “sufficient danger” to necessitate the decision.

“At the beginning of the year, in our meetings, you go over the protocol,” says Davidson, who retired in 2016. “A warning has to be given, and it was. I think it was pretty clear-cut. It’s something you do prepare for.”

The baseball gods might have evened the cosmic scales for L.A. just two days later, when it won a game in the bottom of the 11th inning on a catcher’s interference call after Pirates catcher Angelo Encarnación picked up a pitch in the dirt with his mask. The Dodgers went on to win the West by a game. The forfeit didn’t affect their October entry or their seeding. They were swept by the Reds in the NL Division Series.

In retrospect, it’s easy to say that a ball giveaway night -- while not perhaps as bad an idea as the “Dozen Egg Night” referenced in the movie “BASEketball” -- isn’t brilliant.

But in 1995, people weren’t thinking such things.

“We had had giveaway nights, ball nights, many times in the past, over the years,” Claire says. “So it wasn’t as if this was something new or different from what had been done. What was done in 1995 was different from what’s done today in terms of the protection in every area that needs to be provided. They are totally different considerations.”

The baseball giveaways have gone the way of the forfeits themselves, and we are now in the longest prolonged period between forfeits in MLB history.

Even the NL and AL president roles have been eliminated. When MLB centralized the league office in 1999, Coleman was the lone vote of opposition on the executive council.

He might not have liked the move, but, hey, at least he no longer had to worry about any middle-of-the-night phone calls from umpires.