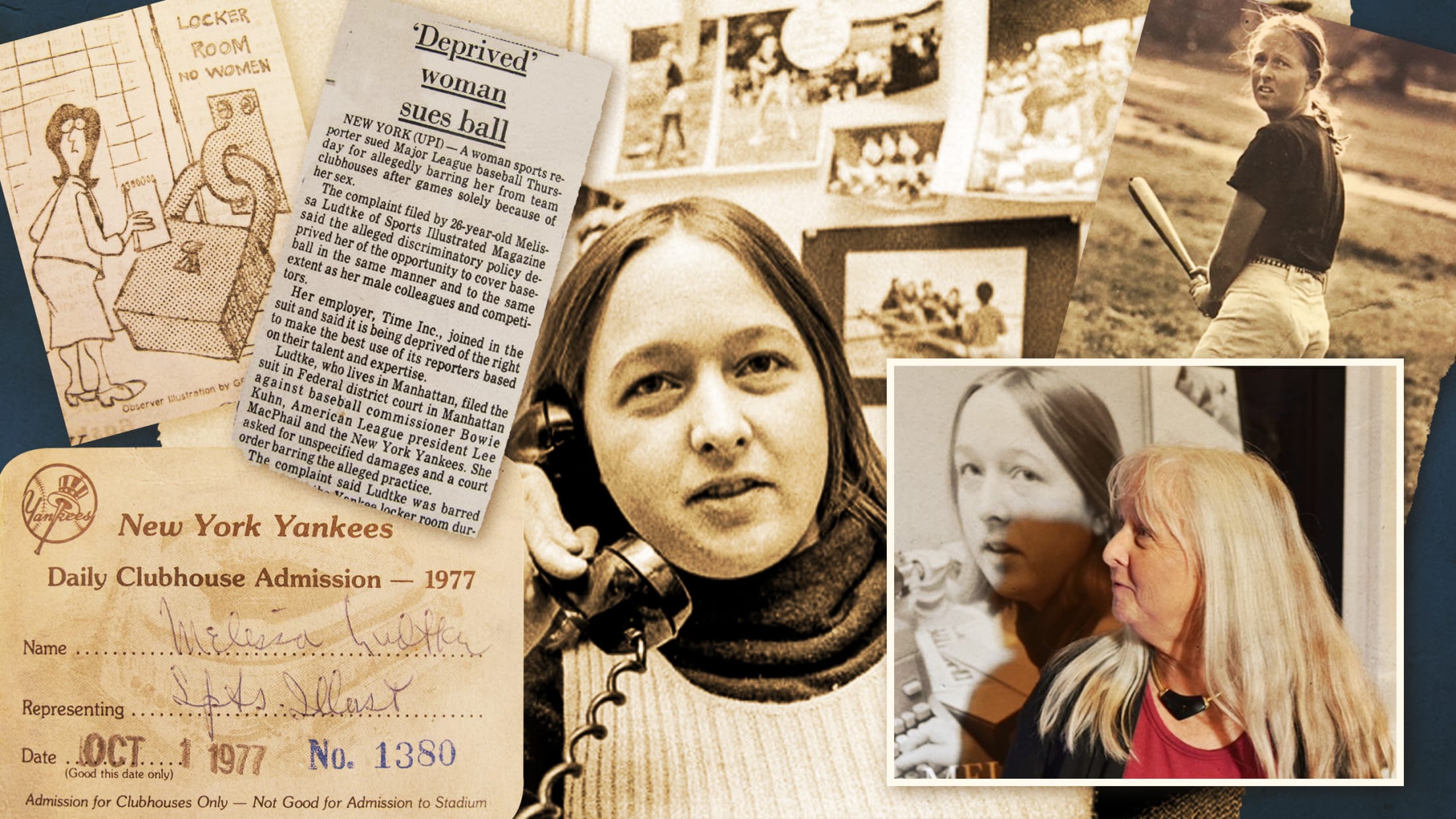

How Melissa Ludtke blazed a trail for women in baseball

It’s not glamorous being a trailblazer. In fact, it can be quite lonely.

When Melissa Ludtke was reporting on baseball in the 1970s for Sports Illustrated, she was the only woman on the beat, in the press box and in the cafeteria. When she was assigned to cover the 1977 Dodgers-Yankees World Series, she was the only woman with press credentials for batting practice and clubhouse access.

She wasn’t actually allowed to enter the clubhouse, as it turned out.

Due to an edict handed down from Commissioner Bowie Kuhn to Ludtke in the middle of Game 1 of the 1977 World Series at Yankee Stadium, she was barred from entering the locker rooms due to a “no women allowed” media policy. Ludtke, who had access to the Yankees’ locker room during the American League Championship Series, had worked throughout the year to gradually warm her male coworkers up to the idea of a woman doing the same job they did, but the door was literally and figuratively slammed in her face at the pinnacle of the season.

This set off a chain reaction that led to a landmark 1978 court ruling, MLB clubhouses opening their doors to women nationwide and, decades later, Ludtke writing a memoir titled “Locker Room Talk: A Woman’s Struggle to Get Inside.” The book is framed cinematically, bouncing between her hearing at the Southern District Court in Manhattan on April 14, 1978, the preceding few months preparing for the case and the hearing’s immediate aftermath.

“If I was going to tell [my story], it was going to be the story of a fight for equal rights and a woman's fight against gender discrimination,” Ludtke said in an interview with MLB.com.

A key pillar of “Locker Room Talk” is the extreme response from the public to Ludtke’s side of the case. Though Ludtke viewed herself as fighting purely for women to have an equal opportunity to report at MLB ballparks, the court of public opinion viewed her as a threat to the male bastion of baseball simply for wanting to do the job she was assigned to do.

Within hours of her lawsuit being announced in December 1977, news columns and cartoons framed Ludtke as invading the sanctity of player privacy by demanding to have equal reporting opportunities as the men … who were already in the locker rooms before and after games.

“We still see this happening to women who put themselves out there for a cause,” Ludtke said, “and how their personal life is so scrutinized and they are made into a characterization of who they often aren't.”

Despite the lack of public support, Ludtke did have figures on her side. In “Locker Room Talk,” she points to baseball writers Roger Kahn and Roger Angell as two of her biggest reporting allies. The Yankees’ PR director at the time, Mickey Morabito, was instrumental to gradually expanding her access throughout the 1977 season, and among the players, Tommy John was one of her most vocal supporters.

Ludtke also received many letters from young women, including a teenager who had been rejected from a job application with the Yankees because being a batgirl was “not an appropriate job for a young girl to have.”

The encouragement wasn’t just from aspiring journalists. It flooded in from women far and wide who felt that they were diminished, marginalized or told “no” solely due to their gender.

“That was something that really sustained me, because suddenly it wasn't just about me, it wasn't about women even my age,” Ludtke said. “It was about younger girls who were saying, ‘I love sports. But when I ask to want to play them … everyone says, ‘That's not something girls do.’ So I love that you're doing this, and one day I want to do it.’ Well, that made such a difference to me.”

Ludtke’s lawyer, Fritz Schwarz (great-grandson of toy store founder F.A.O. Schwarz), crafted an airtight legal argument centered on the idea that because Yankee Stadium at that time was owned by New York City, her case invoked the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause, and therefore Ludtke’s accommodations fell into the “separate, but not equal” bucket.

In the end, Judge Constance Baker Motley ruled in Ludtke’s favor, determining that her ban from the locker room violated her 14th Amendment rights to equal protection and due process, and as a result, Yankee Stadium was legally required to allow her into its locker rooms. However, it wasn’t until Peter Ueberroth succeeded Kuhn as Commissioner in 1984 that official league policy required all MLB locker rooms to allow women reporters.

In Ludtke’s eyes, landing Motley as a judge by complete chance was akin to winning the lottery. Motley was the first woman to be a U.S. federal judge and had carved a noteworthy niche in law, winning multiple racial discrimination cases during the 1960s and working with Justice Thurgood Marshall on the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling.

“She's such a forceful and remarkable character,” Ludtke said. “She's really a hidden figure in history.”

Forty-seven years after the court backed her, why was now the right time for Ludtke to tell her story? She’s been putting the book together for nearly a decade, but her momentum increased over the last couple of years once she realized that her adopted daughter, Maya, was the same age – 26 – as Ludtke was when the ordeal occurred.

She had also noticed that her daughter’s generation knew virtually nothing about the women’s movement in the 1970s, in which Ludtke and her case were major characters.

“It was this real first realization that I was now living history,” Ludtke said, “And that it began to make me think about whether I had an obligation to tell this story as someone who was still alive, who could share this history, and it seemed to me that more and more particularly young women were interested in it.”

***

The baseball landscape for women has changed dramatically since Ludtke’s court case. Women are full-time MLB beat writers all over the country and, for decades, have had the equal clubhouse access that Ludtke fought for so fervently. Women have served as BBWAA president, coaches, broadcasters, Minor League managers and players on Independent League teams. On the surface, the outlook for women in baseball seems to have grown exponentially, especially over the past few years.

Kim Ng became the first woman general manager with the Marlins in 2020 and now sits on the Baseball Hall of Fame’s Board of Directors. Along with Ng, several women have risen in the ranks as MLB front-office executives, including Jean Afterman (Yankees), Elaine Weddington-Steward (Red Sox), Raquel Ferreira (Red Sox), Sara Goodrum (Marlins) and Elizabeth Benn (former Mets director of Major League operations). Rachel Balkovec made history as the first woman Minor League manager with the Yankees’ Single-A Tampa Tarpons in 2022. That same season with the Giants, Alyssa Nakken was the first woman to coach on the field in an MLB game.

Other recent women to make inroads as coaches in MLB organizations include Bianca Smith and Katie Krall (Red Sox), Caitlyn Callahan (Pirates), Rachel Folden (Cubs), Ronnie Gajownik (D-backs) and Jaime Viera (Blue Jays).

The line of progress for women in baseball is not linear, as several of these recent trailblazers are no longer in their groundbreaking roles, including Balkovec (now the Marlins’ director of player development) and Nakken (in a player development role with the Guardians). But Folden, Gajownik and Viera were all still in coaching roles as of the 2024 season, and MLB’s annual Take the Field program has helped dozens of women land roles with Major League organizations since it launched at the 2018 Winter Meetings.

In Ludtke’s field of reporting, women have made strong headway, but they still lag behind their male counterparts in numbers. Of the 681 active BBWAA members in 2024, just 67 (9.8 percent) were women. Claire Smith is the only woman to win the Hall of Fame’s BBWAA Career Excellence Award since it was first handed out in 1962. Three women currently serve as BBWAA chapter chairs: Chelsea Janes (Baltimore-Washington), Jen McCaffrey (Boston) and Meghan Montemurro (Chicago). But in the organization’s 117-year history, only one (Susan Slusser) has served as national BBWAA president.

When considering the current state of women in baseball, Ludtke noted that just because the court rules in a woman’s favor does not mean that floodgates of opportunity suddenly open.

“I don't think that the attitudinal shifts that are necessary have caught up with the legal change,” Ludtke said. “If you have a good lawyer who can argue your case well, you can change the law a whole lot easier than you can change the attitudes around it.”

A truly new frontier for women in baseball, according to Ludtke, will be achieved not when women are still breaking barriers, but when they no longer have to.

“What I'm waiting for,” Ludtke said, “is the seconds, the third, the fourths, to see whether there's going to be room made, or if there's going to be such a backlash from men that the opportunities close down.”

Though there’s work to be done, the on-field landscape for women is still hopeful. Ludtke is optimistic that women MLB umpires are imminent, with Minor League umpire Jen Pawol umpiring Spring Training games in 2024 and being among the pool of umpires eligible for call-up to the Majors.

Clubs are already preparing for the potential arrival of women officials. As of 2024, all 30 MLB teams were required to provide locker rooms for both home and visiting female staff at their Major League and Spring Training ballparks. These requirements also ask clubs to “provide appropriate clubhouse accommodations for female umpires in a space separate from home and visiting Club personnel and in close proximity to the Umpire Room.”

In baseball press boxes and locker rooms alike, women now have a seat at the table.

“I've come to think about it in terms of the pie,” Ludtke said. “Is there only one pie, and there are only so many pieces of that pie that can be cut and eaten, and if you let more people in, there going to be fewer pieces left for the men?

“But then what about if you think about it, why don't we just make more pies?”

***

Today, Ludtke’s relationship with baseball is more informal than it used to be. She resides in Massachusetts, where, in a nod to how her mother raised her, she enjoys listening to baseball games almost exclusively on the radio. Ludtke has brought her daughter up to love the game as well, regularly taking her to Cape Cod League and Lowell Spinners games over the summer and teaching her how to keep score. The more relaxed Minor League environment suited Ludtke best while raising her daughter, embodying what she loved most about baseball.

Occasionally, Ludtke watches games with friends. But as a single mom with a daughter in her 20s, consuming baseball is often a solitary experience for Ludtke these days, involving either a trusted radio broadcast or reading whatever newsletters or stories she can find.

Ludtke fought hard for her place in baseball. As an industry of women stands on the foundation of what she helped build, she has told her story in painstaking detail and can now spend her free time reminding herself of why she was drawn to baseball in the first place.

“I'll always love the game,” Ludtke said. “I really love the game. That was one of the reasons I did the lawsuit, because I couldn't believe that I had this opportunity, and I just wanted to do it. I just loved it.”