This terrible college team invented the shift ... sort of

The once-sure single instead gets gobbled up by a second baseman positioned in the outfield grass. The double play to the right-hand side is scored a 5-6-3, not 4-6-3, because it was the repositioned third baseman who initiated it. The base hit up the middle that ordinarily would have scored the runner from second results only in him advancing to third, because the shifted shortstop swooped in and fielded it 25 feet behind the second-base bag.

From the living room in Middlebury, Vt., where he watches Red Sox games, Gene DeLorenzo keeps seeing these unconventional defensive shifts stealing hits. And though the comment is in jest, the former collegiate coach often turns to his wife, Katharine, and ponders the possible.

“Hey,” the 66-year-old DeLorenzo will say to his bride, herself a highly successful Division III field hockey coach at Middlebury College, “maybe I could be making a whole lot of money now.”

Major League Baseball has assimilated to the abnormal. Infield and outfield shifts are the new normal in a league in which some sort of defensive realignment was applied on roughly one-quarter of all plate appearances last season.

But many years ago, in a tiny Ohio town, at a school known for hippies, artists and left-of-center leanings, where the baseball was bad and the uniforms were uncomfortable and the standings had long since ceased to matter, DeLorenzo and one of his coaching cohorts came up with a scheme so obscure, so original, so outrageous that it threatened to break the game of baseball. It was a shift so extreme that to call it a “shift” doesn’t really do it justice.

This was an almost total reinvention of the game’s defensive alignment.

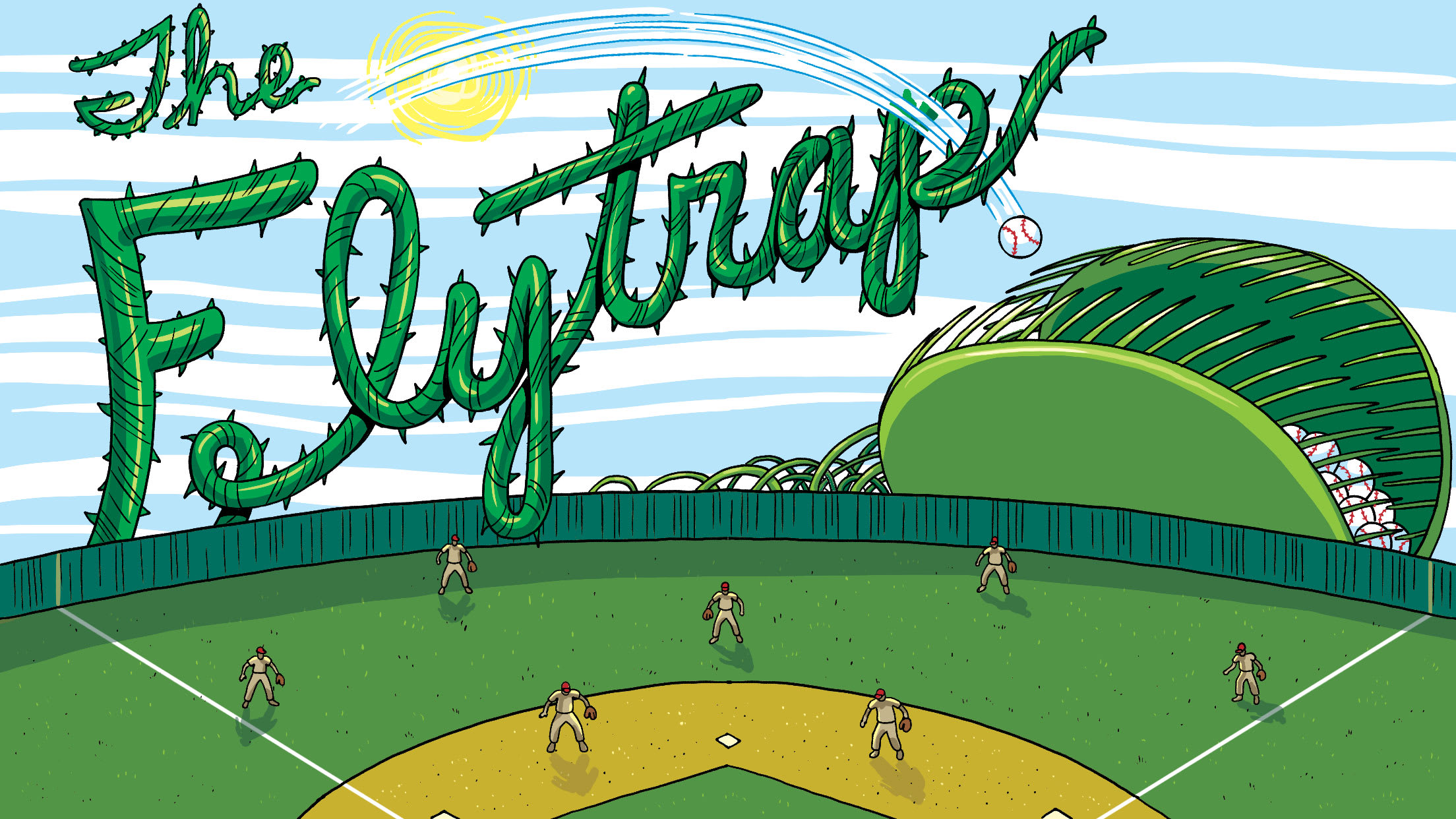

It was called “The Flytrap.” And although some who participated in it were so embittered by the experience that they still don’t want to talk about it, others can reflect on its application, ruminate on its impact and wonder if, perhaps, it was a harbinger of things to come in MLB.

Mostly, though, they laugh. Because The Flytrap was absolutely ridiculous.

* * * * *

The 1994 Oberlin College baseball season was unfolding the way Oberlin College baseball seasons tended to unfold at that time. The Yeomen were 1-14, entrenched in the basement of the Division III North Coast Athletic Conference. The roster was comprised of students studying pre-med or math or voice or other disciplines at a private liberal arts college and music conservatory where -- get this -- athletics were secondary to academics.

“We were,” in the estimation of then-freshman pitcher and outfielder Will Marbury, “not good.”

The program was scattered. Head coach Jeff White was assisted by DeLorenzo, who was also Oberlin’s head men’s basketball coach, and B.J. Connolly, a member of the football coaching staff. It was a condition of employment that coaches help with more than one sport, so, for DeLorenzo and Connolly, the baseball role was a side gig and, largely, a lark.

It was that way for some of the players, too. Oberlin didn’t expend much energy recruiting its ballplayers, even as other DIII programs in the area unearthed strong talent. The baseball unit was a glorified club team, and it included, in that ’94 season, a sophomore outfielder named Erin Marks, who was believed to be just the third woman to suit up for an NCAA baseball team.

The best player on the team was a sophomore named Ted Lytle, who ranked among the conference leaders in stolen bases that season. But if you’re looking for someone to reminisce fondly about his “glory days,” he’s not your guy. In his four years at Oberlin, he had three head coaches. Lytle had been on a winning high school team, so he knew what a successful squad looked like.

He knew Oberlin wasn’t it.

Even if Oberlin had managed to compile more baseball talent than it did, it’s unlikely that talent would have been maximized in the burdensome uniforms the Yeomen were forced to wear.

“It was hotter than hell,” Lytle says. “It was a high percentage of wool. We’re talking really old school. So not only did we have some of the slowest people around, they put you in these uniforms that dehydrate you and almost give you heat stroke.”

This was not, therefore, what you would call an impenetrable, unshakable operation. The Yeomen were doomed to failure, with no pretense that they would or should be better. Losses were less a source of frustration and more a source of identity. There were nine teams in the North Coast Athletic Conference. Eight would reach the conference playoffs.

You can guess which one would be staying home.

It is often against a backdrop of nonexistent expectation that creativity can truly flourish. As Bob Dylan famously sang, “When you ain’t got nothing, you got nothing to lose.” So it was with the Yeomen. Not only was this a terrible baseball team, it was a terrible baseball team at an eccentric school that, then and now, celebrates creativity and quirkiness. Oberlin, which counts entertainment visionaries James Burrows, Lena Dunham and William Goldman among its many notable alumni, has often been characterized as a place for outcasts and creative minds.

The school even, in some respects, boasts a legendary baseball alum. Way back in 1881, Oberlin’s inaugural team included a catcher named Moses Fleetwood Walker, who would go on to play in the American Association and thus technically become the first African-American to play in the Major Leagues.

“Oberlin College,” DeLorenzo says, “was a unique environment with very intuitive and bright individuals.”

The conditions, therefore, were ripe for invention. And that got DeLorenzo and Connolly thinking …

*****

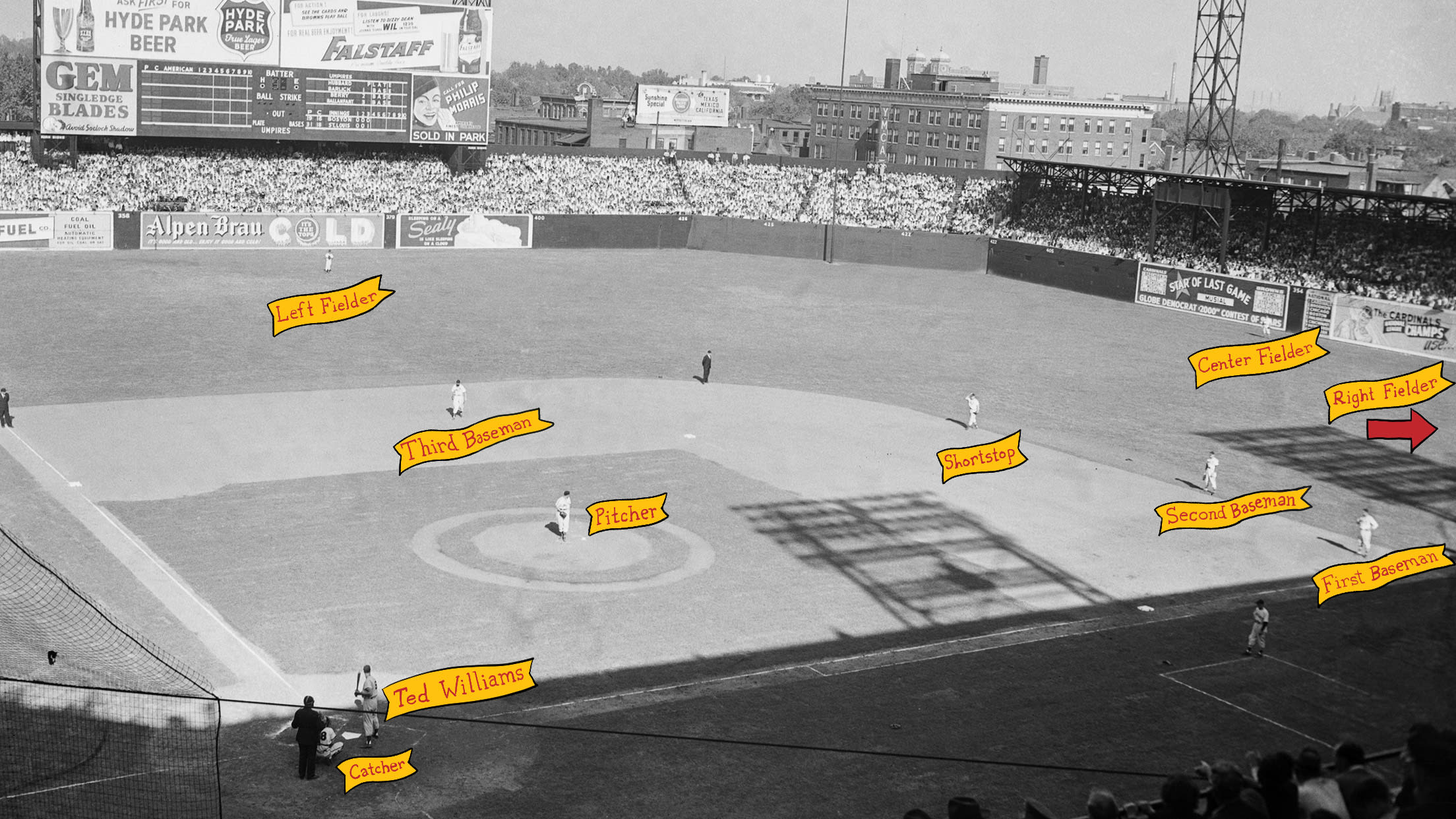

Though there are claims that it may have been used as early as the 1920s, the baseball shift as we know it today is often said to have truly been born on July 14, 1946. That’s when Cleveland player/manager Lou Boudreau, in a desperate attempt to slow the steady battering his ballclub was taking at the hands of Ted Williams, put six men on the right-hand side of the field, leaving only left fielder George Case on the left side, about 20 feet behind where the shortstop would traditionally stand.

It was considered heresy, an attack on the soul of the sport. Williams himself laughed when he first saw it. But the Williams Shift, as it came to be known, succeeded in getting inside the head of perhaps the greatest pure hitter the game has ever seen. It may even have had an outsize impact on the outcome of that year’s World Series, during which the St. Louis Cardinals used a variation of the Williams Shift and limited the Splendid Splinter (who, in fairness, was playing hurt) to a meager 5-for-25 showing.

One day in April 1994, not more than 40 miles from where Boudreau’s ballclub was based, DeLorenzo and Connolly met for several hours to hatch a new way of doing defense that, much like the Williams Shift, would be aimed at obstructing opponent offense. Their target, though, was not a single player or a single type of swing. They weren’t aiming only at pull power; they were aiming at their club’s own overall ineptitude. If their team stunk at baseball, and the team’s complexion wasn’t changing, well, then, the only answer was to change the game itself.

DeLorenzo came from a basketball background and Connolly football; their signature sports had a shared defensive design.

“Motion,” DeLorenzo says.

At a very basic level, basketball teams alternate between man-to-man and zone systems, and, within the zone, between 1-3-1 and 2-1-2 alignments. Football teams might use the 4-3 front or the 3-4 front. They might go nickel or dime or prevent, depending on the game situation and opponent strength.

In both sports, ultimately, defenses adjust to their opponents, provide multiple looks and cover ground out of practicality, not predestination.

The hard truth faced by the Yeomen was that opponents were pummeling their pitchers, smacking frozen ropes into the outfield gaps and enjoying a Gas House Gorillas-style conga line around the bases. Oberlin’s losses weren’t just routine; they were routinely lopsided.

So, DeLorenzo and Connolly thought, what if Oberlin made the type of adjustment that would be made in basketball or football?

“We wanted,” Connolly says, “to put people where we thought [they’d have] a chance to catch the ball or keep it in front of ‘em.”

It didn’t take a thorough examination of the box scores to know that the answer, by and large, was in the outfield. If Oberlin could limit opponents to singles as opposed to extra-base hits, maybe, just maybe, it could keep the games close, run into a little luck on the offensive side and produce some more respectable results.

* * * * *

Inspired by the blank canvas presented by their atrocious team, DeLorenzo and Connolly came up with a truly original alignment -- two infielders (one on each side of second base), five outfielders, a pitcher and a catcher. But in keeping with the colossal change and the bent toward a football and basketball mindset, all of those positions were renamed.

The two infielders were not a shortstop and a second baseman but a “sweeper” on the left-hand side and a “stud” on the right.

The five outfielders were known as the “left guard,” “left gapper,” “right gapper,” “right guard” and “rover.” The guards were positioned about five feet off the first- and third-base lines, halfway between the base and the outfield fence. The gappers were in left- and right-center, a few steps in from the warning track. The rover was in shallow center field.

The pitcher was the “point,” and the catcher was the “safety.”

Depending on the game situation -- and in keeping with the “motion” mindset -- the outfield could be reconfigured. One batter might face four outfielders and three infielders, another five infielders and two outfielders. But the standard alignment (if you can call any of this “standard”) would be two on the dirt and five on the grass, with a goal of the “point” inducing fly balls and the fielders swallowing them up.

The Flytrap … Get it?

We were going to be the laughingstocks of the conference. But then again, we were already the worst team there was in that conference.

Of course, The Flytrap requires fly balls. To generate those, Connolly and DeLorenzo decided that the Oberlin pitchers could lob the ball, Rip Sewell-style, high over the plate to encourage the opposing hitter to swing up.

“We had to talk to the umpires to see if the strike zone included vertical versus just horizontal,” Connolly says. “So if the ball came down from on top of the plate, 10 feet high, is that considered part of the strike zone?”

They got the OK. They were ready to set the trap.

“We did wonder what everyone was going to think of us,” Connolly says. “We were going to be the laughingstocks of the conference. But then again, we were already the worst team there was in that conference.”

Connolly and DeLorenzo pitched their idea to White, who was a true baseball man but not a tough sell. Just a week earlier, in assessing how previously winless conference-rival Denison was able to put up 28 runs in a doubleheader against Oberlin’s porous defense, White had told the school paper, The Oberlin Review, “Putting it in play is about [all] you have to do.” Heck, in the first game of the doubleheader that preceded the proposal, White watched his starting pitcher give up 20 earned runs in 2 2/3 innings.

So, yeah, White was on board.

At the following practice, the coaching staff introduced The Flytrap to the players by announcing that from that point forward, the “Yeonine,” as the Review referred to them, would be spreading out that nine quite a bit differently. The coaches handed out a manual, written with a liberal application of uppercase, that described the goals of The Flytrap and implored each player to “disassociate from the standard baseball defensive mode of thinking and FREE his or her mind to a NEW concept of defense.”

“The coaches said they had taken a look at our last game that we had lost, like, 15-2,” says Marbury, “and that, if we had gone with this Flytrap defensive alignment, we would have won the game 2-1, because all the balls were hit in the gaps and down the lines.”

This theory would prove to have holes -- specifically, holes on the infield corners.

But Oberlin was desperate, and from that desperation emerged a willingness to take a chance.

“These were bright people,” Lytle says of the coaches. “They might not have known how to play baseball, but they were smart people. So while it was a little like being thrown into a test tube, I had a relatively open mind that it was worth giving it a shot.”

* * * * *

On Wednesday, April 20, 1994, the Oberlin baseball team took the field for the first inning of a doubleheader against conference foe Case Western Reserve University. The players trotted out to their traditional positions. All was calm and placid at Dill Field as left-hander Noah Pressler picked up the ball and put it in his glove.

But then Pressler, who was nicknamed “Moose,” stepped off the mound, turned his back to the batter, took a deep breath, and screamed, “Mooooooose!”

Suddenly, all of the Oberlin fielders sprinted to new spots. There were five outfielders. There were two infielders (Lytle at sweeper, Marbury at stud). The Yeomen had repositioned themselves so swiftly, so unexpectedly and so originally that all the batter could do was stand there, astonished and spellbound.

That is until he -- and his entire dugout -- started laughing.

Some of the Oberlin players were doing the same.

“I was laughing so hard, I had tears in my eyes,” Marbury says. “It was so ludicrous.”

Now that The Flytrap had been unveiled, it was time to see if it was capable of limiting an opponent’s offense. The defense hinged on the premise that the pitcher -- er, the point -- would execute the eephus expertly and summon fly balls, not free passes.

It didn’t quite go that way.

“Unfortunately,” wrote student Dave Milstead in the Review, “Pressler and his eephus induced many walks, many delays of game, and many stares of disbelief from the sparse crowd on hand.”

The walks were only part of the problem, though. Another issue was the availability to the offense of that tricky little baseball tactic known as the bunt. Turns out it is pretty difficult to defend a bunt when you don’t have anybody manning first or third base.

“Our theory was to take these guys hitting doubles, triples and home runs and make them make a choice,” DeLorenzo says. “You want to bunt? Fine. A bunt single is a bunt single.”

That’s the refrain you’ll often hear from big league managers when they justify shifting against the likes of Joey Gallo and Cody Bellinger. “If [insert name of All-Star] is thinking about bunting, that’s a win for us.”

Of course, bunting against a Major League hurler is a lot tougher than laying one down against a telegraphed DIII eephus pitch. Not to mention that a single can quickly become what amounts to a double when there’s nobody at first to hold the runner. The Yeomen had practiced some trick plays to circumvent this -- pitchouts behind right-handed batters to cut down the distance of the safety’s (catcher’s) throw to a streaking Lytle at third on steal attempts, and pickoff attempts in which the goal was to toss the ball to the fleet-footed Lytle and let him chase the runner.

But they didn’t work in an actual game.

“Someone gets on base, and the minute [the point] toes the rubber, the runner takes a lead halfway to second and I’m behind him still,” says Marbury. “So it was not real well thought out as to how the strategy would change. It was lunacy.”

For both games that day, the Oberlin “points” were, much like their pitching predecessors, prone not only to issuing walks but to giving up batted balls that found grass, even with the extra outfielders. Although the alignment might have put Oberlin in a better position to deny extra-base hits, the five players positioned in the outfield were neither swift enough nor skilled enough to get to every ball.

If The Flytrap had any benefit, it was showcasing Lytle’s athleticism. A track star whose school records in the indoor 400- and 500-meter dash still stand, Lytle -- as DeLorenzo remembers it -- fielded a two-hopper in front of the second-base bag and -- with the pitcher/point lax to cover first on this particular play -- sprinted to the first-base bag himself just in time to nab the runner.

We did cut down on errors. Probably because they bunted all the time and then just ran around the field.

Alas, that wasn’t a repeatable plan for every ground ball. On bunts to the first-base side, Marbury had to hustle to the bag from the stud position and field the throw from the pitcher.

“I had to sprint, catch the ball, tag the base and not get knocked over,” Marbury says. “I did not have the coordination to do that without getting run over.”

Sure enough, on one such play, Marbury did get tangled with a burly baserunner.

“I got trucked,” he says. “The guy kept running like I was a fly.”

And so it went in The Flytrap’s dud of a debut. The Yeomen lost both ends of the doubleheader, 10-3 and 12-3.

Still, the experiment persisted. Into the weekend, at least.

Next on the docket was a doubleheader against the Wooster Fighting Scots, and the plan -- the hope -- was for the kinks and quirks of The Flytrap to be smoothed over and for the perceived benefits of the alignment to shine through.

That didn’t go so well, either. The Scots banged out 33 hits over the two games and also swiped 14 bags.

“We did cut down on errors,” Marbury says. “Probably because they bunted all the time and then just ran around the field.”

As had been the case against Case, the opposition was incredulous.

“When you see [The Flytrap] for the first time, it’s a little startling and a little confusing,” says current Wooster head coach Barry Craddock, who was a pitcher for the Scots at the time. “But it didn’t work. At all. They really couldn’t defend any steals. And having the pitcher cover first base on ground balls was pretty interesting, to say the least. They are the Yeomen, and that was yeomen duty.”

Oberlin lost those two games, 12-0 and 22-0. And with only three games left on the schedule (the Yeomen would forfeit two of them so the players could study before finals rather than waiting out the rain in the forecast) and last place in the conference clinched, the decision was made to swat The Flytrap.

“The idea had been to take away the strength of the other team,” says Marbury, now a high school math teacher and baseball coach in Baltimore. “The problem was, their strength was that they were much better baseball players than we were.”

* * * * *

The Flytrap didn’t earn Oberlin any wins, but it did earn the school some attention.

Tucked into the “Scorecard” section penned by Jack McCallum in the June 6, 1994, issue of Sports Illustrated, beneath notes on Darryl Strawberry entering rehab at the Betty Ford Clinic and Duke coach Mike Krzyzewski flirting with a move to the NBA, was a 446-word brief about the Yeomen’s quirky concoction. The issue came out several weeks after the season ended, had some minor factual errors, and may have overstated The Flytrap’s success in limiting extra-base hits, but the article succeeded in sharing Oberlin’s unconventional idea with the masses and getting a few chuckles.

“We weren’t trying to make it farcical,” DeLorenzo says. “We were just trying to win, trying to do it a different way.”

What they were missing, notably, was the data that dictates defensive positioning in today’s game.

“We didn’t play that many games in northeast Ohio,” says Lytle, who is now an anesthesiologist for University Hospitals in the Cleveland area. “So there was not a lot of data to draw from. And with the coaching turnover we had, it was not something that was going to survive long enough to look at the data.”

Oberlin made no effort to refine and improve upon The Flytrap the following year. Though Connolly took over for White as the head baseball coach for the ’95 season, he continued to focus primarily on football, while DeLorenzo was bound to basketball. Both of The Flytrap’s founders left the school later in the 1990s, their invention merely a small and hazy memory from that formative period in their professional lives.

“I think Oberlin made me a better coach,” says Connolly, now the tight ends coach at Wofford College. “It made me think outside the box.”

The Flytrap has long since faded into obscurity at Oberlin, where no records, photos or rosters from 1994 could be found by the school’s athletics communications department. The Yeomen baseball team left behind the wool unis and, over time, became a respectable program, even winning the 2015 North Coast Athletic Conference championship game.

For such Oberlin alums as Blue Jays assistant general manager Joe Sheehan, who played baseball for the Yeomen from 2002 to 2006, the legend of The Flytrap was, sadly, not passed down. But having been introduced to the idea for the purposes of this story, Sheehan, whose role with Toronto revolves around the application of analytics, could admit that while The Flytrap itself was ludicrous, DeLorenzo, who has since retired from collegiate coaching, and Connolly were, oddly, onto something.

After all, they were talking about blowing up the traditional defensive alignment long before MLB’s statheads did exactly that.

“Even in the last five years, we’re seeing so many changes in the game,” Sheehan says. “We’re seeing infielders in the outfield, we’ve seen teams take the pitcher and put him in left field, we’re seeing guys fill multiple roles, we’re seeing real two-way players. There’s definitely more athleticism and flexibility in the game. It’s a cool pendulum swing.”

The pendulum will quite likely never swing far enough for The Flytrap to mount a comeback. But in the 2019 season, 185 plate appearances in MLB ended with the defense in a four-outfielder arrangement, including 86 instances in which a fifth fielder was positioned in the outfield grass, at least 160 feet from home plate.

So if, from his Vermont living room, DeLorenzo watched his Red Sox closely on the night of Sept. 20, 2019, he would have noticed something interesting. In the ninth inning of a game against the Rays at Tropicana Field, Mitch Moreland, Boston’s left-handed-hitting, pull-prone first baseman, stepped to the plate with a runner on, one out and the Red Sox trailing, 4-2. Looking to lock down their late lead and mystify Moreland, the Rays -- the team widely credited with expanding the scope of shifting in the late 2000s -- positioned their left fielder in left, their center and right fielders in the power alleys, their second baseman in deep right, their shortstop in shallow right, their third baseman behind and to the right of the second-base bag and their first baseman behind the first-base bag, at the infield lip.

Five outfielders, two infielders. It wasn’t exactly the defensive scheme DeLorenzo and Connolly had drawn up a quarter-century earlier, but it was a whole lot closer than any members of the 1994 Oberlin Yeomen could have possibly imagined seeing at the big league level back then. It was an MLB variation of The Flytrap.

Then Moreland hit a game-tying home run.

Foiled again.

A version of this story originally ran in February 2020