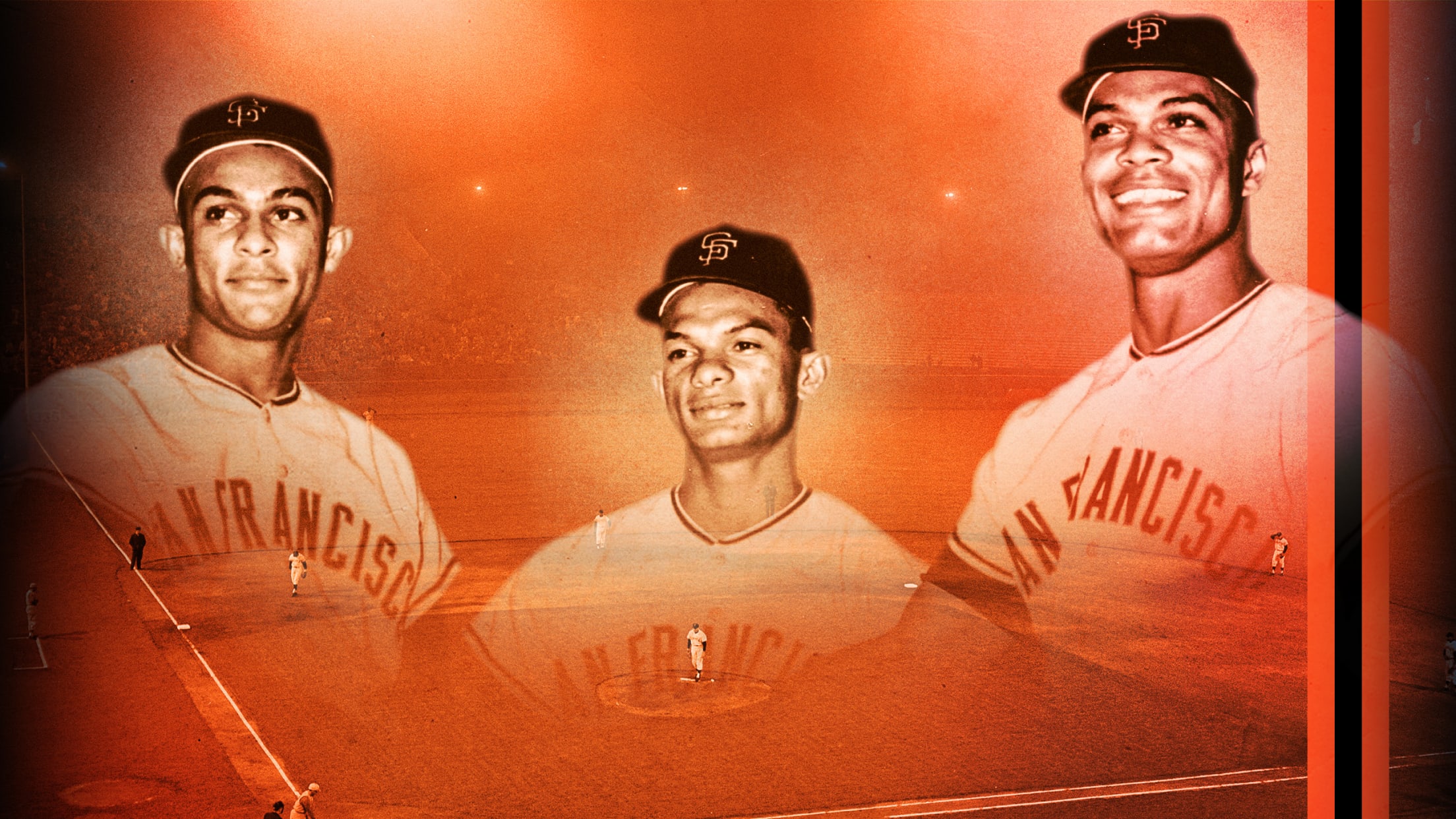

60 years ago, the Alous formed the first all-brother outfield

In a sport that regularly sees decades-old records fall, it may seem like a folly to declare that a particular accomplishment will never be matched. But there’s one feat we can be confident we will never witness again, and it happened 60 years ago, on Sept. 15, 1963, when Felipe, Mateo and Jesús Alou of the San Francisco Giants appeared in what was the first -- and still the only -- “all-brother” outfield in Major League history.

Felipe, who started the game in right field, was the only Alou in manager Alvin Dark’s starting lineup against the Pirates at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field that Sunday. According to an article in the San Francisco Examiner, when Jesús made his Major League debut five days earlier, Dark said that he hoped to have a 10-run lead at some point in order to get all three brothers into the outfield at the same time. His plan, he said, was to have Felipe, the oldest at age 28, in center, with Mateo, 24, and Jesús, 21, flanking him in left and right.

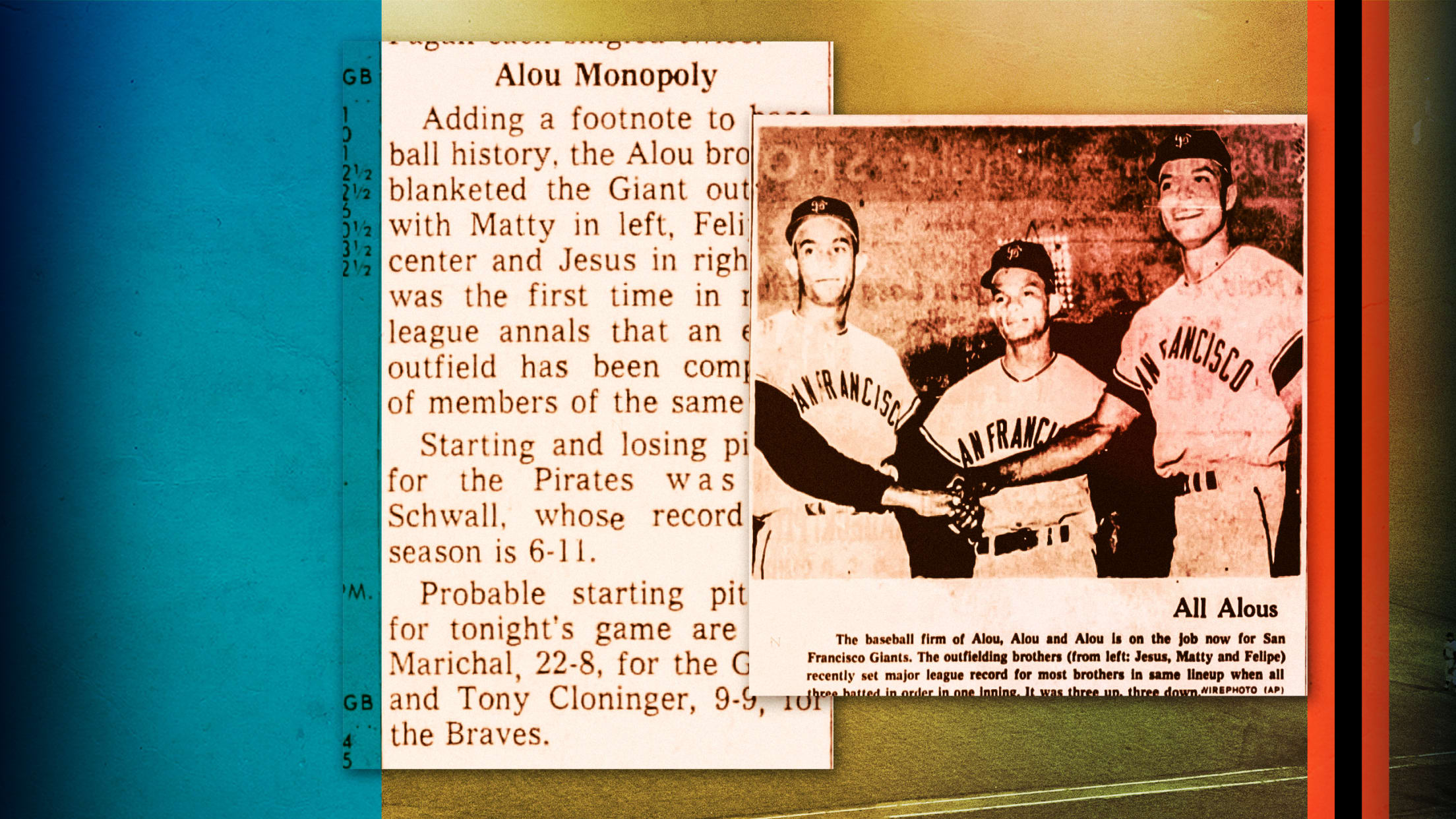

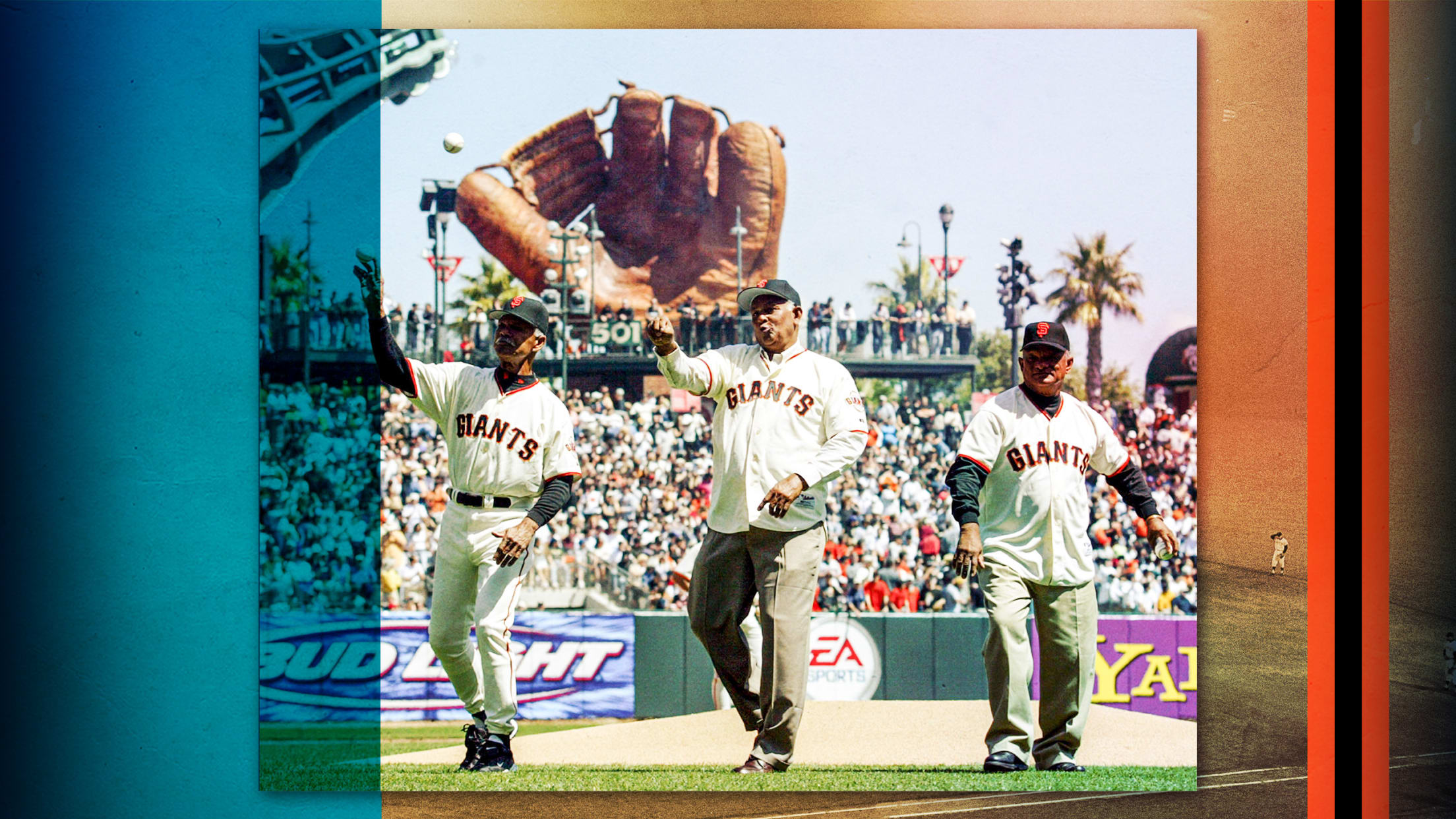

The Giants, however, had a more modest 8-3 lead over the Pirates in the bottom of the seventh on Sept. 15, when Dark moved Felipe to left field, removing future Hall of Famer Willie McCovey from the game, and put Jesús in right. After the Giants extended their lead to 12-3 in the top of the eighth, Dark moved Felipe to center, displacing another future Hall of Famer, Willie Mays, and inserted Mateo in left.

San Francisco played the last two innings with an all-Alou outfield.

In center field for the Pirates that day was Manny Mota, who in 1962 became the 11th Dominican-born Major Leaguer when he debuted with the Giants. He calls it “a great honor, a great privilege” to have witnessed that historic outfield.

“For me, Mateo and Jesús were like brothers, people I admired and cared about, just like Felipe," Mota, 85, said in Spanish, via phone. “It filled me with pride to see them play together and gave me a lot of joy and satisfaction."

Though it was a historic moment in the Majors, for Felipe, Mateo and Jesús, it didn’t register as significant because they had patrolled the outfield together for their winter ball team, the Leones del Escogido. “We had played many years together with Escogido,” Felipe, 88, said in Spanish during a phone interview from his home in Boynton Beach, Fla. “For us, it was not a big deal.”

An Associated Press story that appeared in newspapers around the country the following day read: “Adding a footnote to baseball history, the Alou brothers blanketed the outfield.”

But while the game itself might have been inconsequential in the standings -- the Giants entered the day in fourth place in the National League with an 11-game deficit -- 60 years later, it’s clear that Felipe, Mateo and Jesús Alou were hardly a footnote.

‘A singular story’

Felipe, Mateo and Jesús Rojas Alou, three of six children born to José Rojas and Virginia Alou, grew up in the 1940s, playing baseball near their humble home on Kilometer 12, a locality on the southern coast of the Dominican Republic. Like many other Dominicans of that time, the Rojas-Alou family was extremely poor, and the brothers rarely had proper balls or bats or gloves. And though there were Dominican players active in the Negro Leagues and circuits around the Caribbean, a career in professional baseball was not yet something a young man from the 18,704-square-mile nation could realistically dream of.

Instead, Felipe, the oldest of the children, planned to study medicine with the financial support of a maternal uncle, a captain in the Dominican army. As a student-athlete, Felipe excelled at track and field, making the Dominican national team while enrolled at the University of Santo Domingo. That’s how he found himself representing his country at the 1955 Pan American Games in Mexico City.

Felipe was there to run sprints and throw the javelin. However, when the Dominican baseball team sent a player home as a disciplinary measure, Felipe was asked to switch sports. In the final game of the tournament against a U.S. squad, Felipe racked up four hits and the D.R. captured the gold medal.

Felipe’s performance caught the attention of a bird dog scout for the New York Giants named Horacio “Rabbit” Martínez, a Dominican shortstop who had played for the New York Cubans of the Negro Leagues, a team owned by future Hall of Fame executive Alex Pompez. In 1955, Pompez was working as a scout for the Giants. Martínez was the athletic director at the University of Santo Domingo while also evaluating talent for Pompez.

Following Martínez’s recommendation, Pompez signed Felipe, who projected as an outfielder with his strong javelin-throwing arm. Thanks to the efforts of Martínez, Pompez and another early scout in Latin America, Frank Genovese, the Giants would later ink Mateo and Jesús, as well as other Dominican pioneers like Mota and pitcher Juan Marichal, a teammate of the Alou brothers on the Giants, who in 1983 became the first Dominican-born player to enter the Hall of Fame.

• Looking back at Marichal's Top 10 moments

José and Virginia reluctantly gave Felipe permission to sign with the Giants. And the need to bring in income for his family sooner than later led Felipe to accept the offer and embark on a journey no one else had ever made.

A road not traveled

Given Dominicans' sizable presence in the Majors today -- there were 104 Dominican-born players on 2023 Opening Day rosters -- it’s hard to imagine a time when the sport was devoid of Dominican players. But that was the case when Felipe Rojas Alou began his Minor League career in 1956 with the Lake Charles Giants, the team’s Class C affiliate in the Evangeline League in Louisiana. Osvaldo “Ozzie” Virgil, the first Dominican-born Major Leaguer, wouldn’t make his big league debut until September of that year.

One of the many twists of fate that makes the “all-brother” outfield remarkable, is how “extremely close,” to use his own words, Felipe came to returning to his country to renew his studies and forgetting about playing Major League Baseball.

That’s because in addition to finding himself alone in a foreign country where he didn’t speak the dominant language, as a Minor League player in the deep South in the 1950s, Felipe had to endure the indignities of segregation. Like many African Americans and Afro-Latinos of the era, as the son of a white mother and a Black father, he couldn’t dine at restaurants with his white teammates or enter ballparks through the same door.

Felipe’s time in Lake Charles was short-lived; Louisiana law barred Black players from participating in the Evangeline League. So after just five games with Lake Charles, Felipe found himself making a three-day bus journey to Cocoa, Fla., to join the Giants’ Class D affiliate. The team had already purchased his return ticket to the Dominican Republic, so Felipe thought about continuing on to Miami and taking a flight home.

“I could have gone home and never returned,” said Felipe. “But I thought of Horacio Martínez and I said to myself, ‘You can’t leave.’ Plus there was poverty at home.”

Those hardships aren’t lost on Felipe’s son, current Yankees third-base coach and former Mets manager Luis Rojas.

“Many of us, coaches and players these days, have some basic knowledge of the second language and we know something about the culture,” Rojas said, in Spanish, on a recent afternoon at Yankee Stadium. “But I’ve always thought about how, in those days, he traveled alone without any way of finding addresses or communicating like we have now and still felt comfortable enough to display his talent, because all that can affect your performance.”

Injustice and activism

With four letters, three of them vowels, A-L-O-U is a recurrent New York Times crossword puzzle answer, having appeared more than 250 times in reference to clues such as “Any of three major-league brothers” or “Baseball’s Felipe, Matty, Jesús or Moises.” Moises, of course, is Felipe’s son and former Major League outfielder

Yet the name that carried the family to fame in the U.S. is the result of an error.

At some point, a Minor League official, presumably unfamiliar with Latin American naming conventions, mistook the family matronym, Alou, for Felipe’s paternal last name. That’s how Felipe ended up with a jersey that said “ALOU” instead of his actual last name, Rojas. (To this day, Alou is also commonly mispronounced in the U.S. as “AL-OO” instead of the proper pronunciation “AL-OH.”)

Because he had yet to master English, and there was no one to serve as an interpreter, Felipe was powerless to do anything about the mistake. So it stuck. Later, when they began their own baseball careers, Mateo and Jesús also chose to go by the last name Alou in the U.S. to be associated with Felipe.

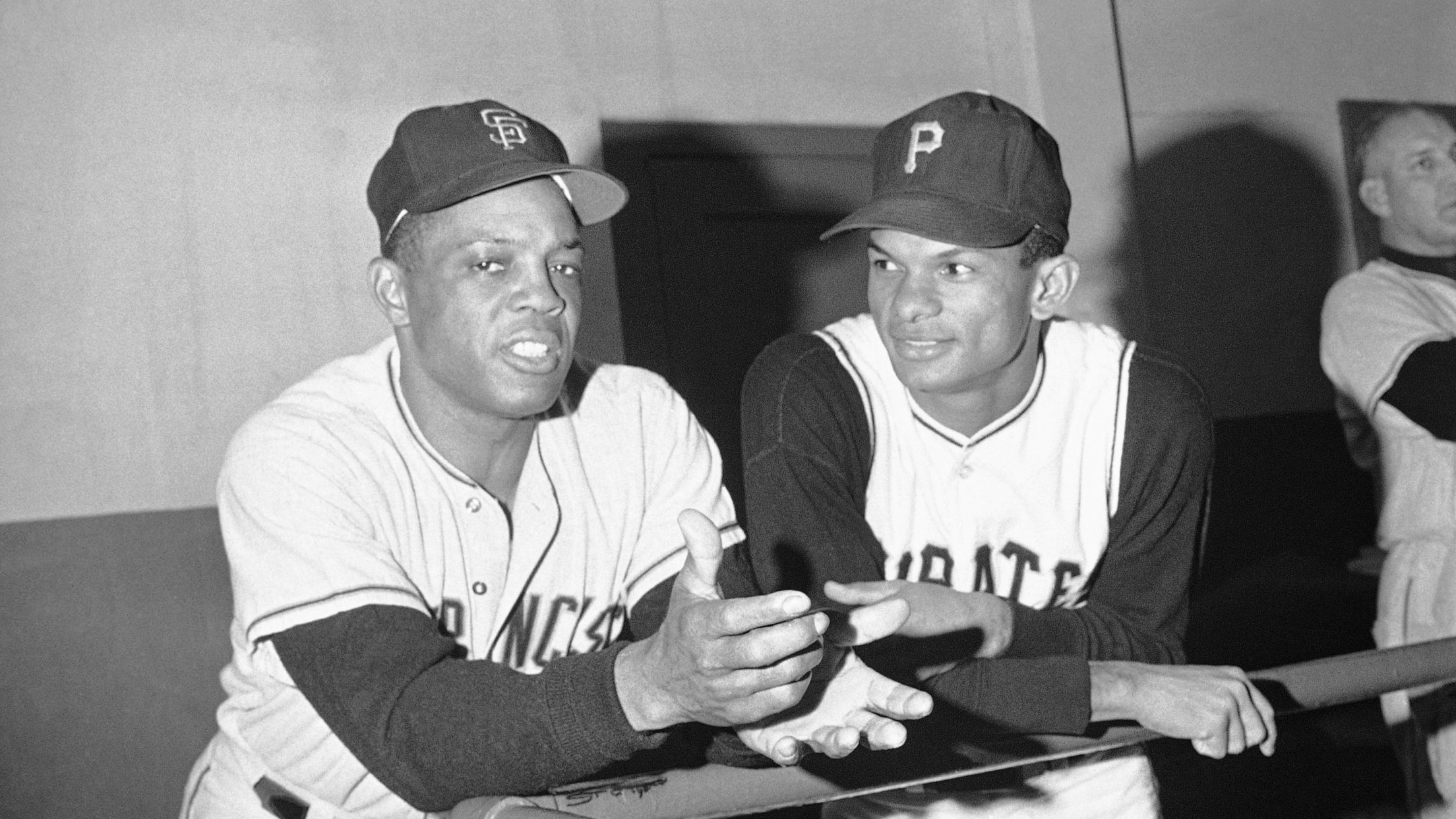

Felipe made his big league debut with the Giants on June 8, 1958, becoming just the second Dominican-born player and the first signed out of the Dominican to play in the AL or NL. (Virgil moved to New York City in his youth and had been signed out of high school.)

Mateo joined his big brother in San Francisco two years later, in 1960. Jesús was playing in just his sixth Major League game when he became part of the all-brother outfield on Sept. 15, 1963.

Adrian Burgos Jr., professor of history at the University of Illinois and author of the books "Playing America's Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line" and "Cuban Star," a biography of Pompez, notes that the all-Alou outfield is all the more striking when considered in the context of U.S. and Latin American history.

In addition to the racism, bigotry and xenophobia the first wave of Dominican players had to contend with in the States, the early 1960s were also a time of great political and social unrest in the Dominican Republic, with the assassination of dictator Rafael Trujillo in 1961, which was followed by a military coup and a U.S. invasion.

“The story of the Alou brothers is really singular in baseball history,” says Burgos. “We should understand all the things that were surrounding the moment, historically and socially, and that they still were able to make it.”

Injustice didn’t end in San Francisco; in his autobiography, "Alou: My Baseball Journey," published in 2018, Felipe recounts how at one point, before Jesús joined them in San Francisco, Dark -- the same manager who would orchestrate the all-brother outfield -- forbade him and the other Latin American players, including Mateo, Marichal and Puerto Rican first baseman Orlando Cepeda, from speaking Spanish in the clubhouse, a mandate that they defied.

And prior to the 1963 season, Major League Baseball Commissioner Ford Frick fined Felipe $250 for playing in a baseball game in the Dominican Republic that pitted a local team against a team of Cuban players living in the U.S. The experience led Felipe to author an essay with journalist Arnold Hano titled “Latin American Players Need a Bill of Rights,” which appeared in a 1963 issue of Sport magazine.

In it, Felipe explained the pressure to play in that game because the request came from the military junta that ran his country at the time, and also his need to supplement his income during the offseason. Players from Latin America, he argued, needed someone inside the league to look out for their interests. That essay led the Commissioner's Office to hire Cuban-born executive Bobby Maduro in 1965 as “coordinator of Inter-American baseball.”

“[Felipe] was insistent that Major League Baseball needed to understand the circumstances of Dominicans, Latinos, Latin American players,” says Burgos.

Separate ways

Sept. 15, 1963, wasn’t the first time that the Alou brothers made big league history. Four days earlier, on Sept. 10, they’d become the first trio of brothers to appear in a Major League lineup at the same time, though they didn’t play the outfield together. Felipe started the game in right, and Mateo and Jesús entered the game as pinch-hitters in the eighth inning.

And Sept. 15, 1963, wasn’t the only time that Felipe, Mateo and Jesús Alou manned the outfield at the same time for the Giants. They did so again on Sept. 17 and Sept. 22 of that year, though they never started a game together in the outfield.

“Having something like that happen was difficult,” says Virgil, 91. “A great achievement for Dominican ballplayers.”

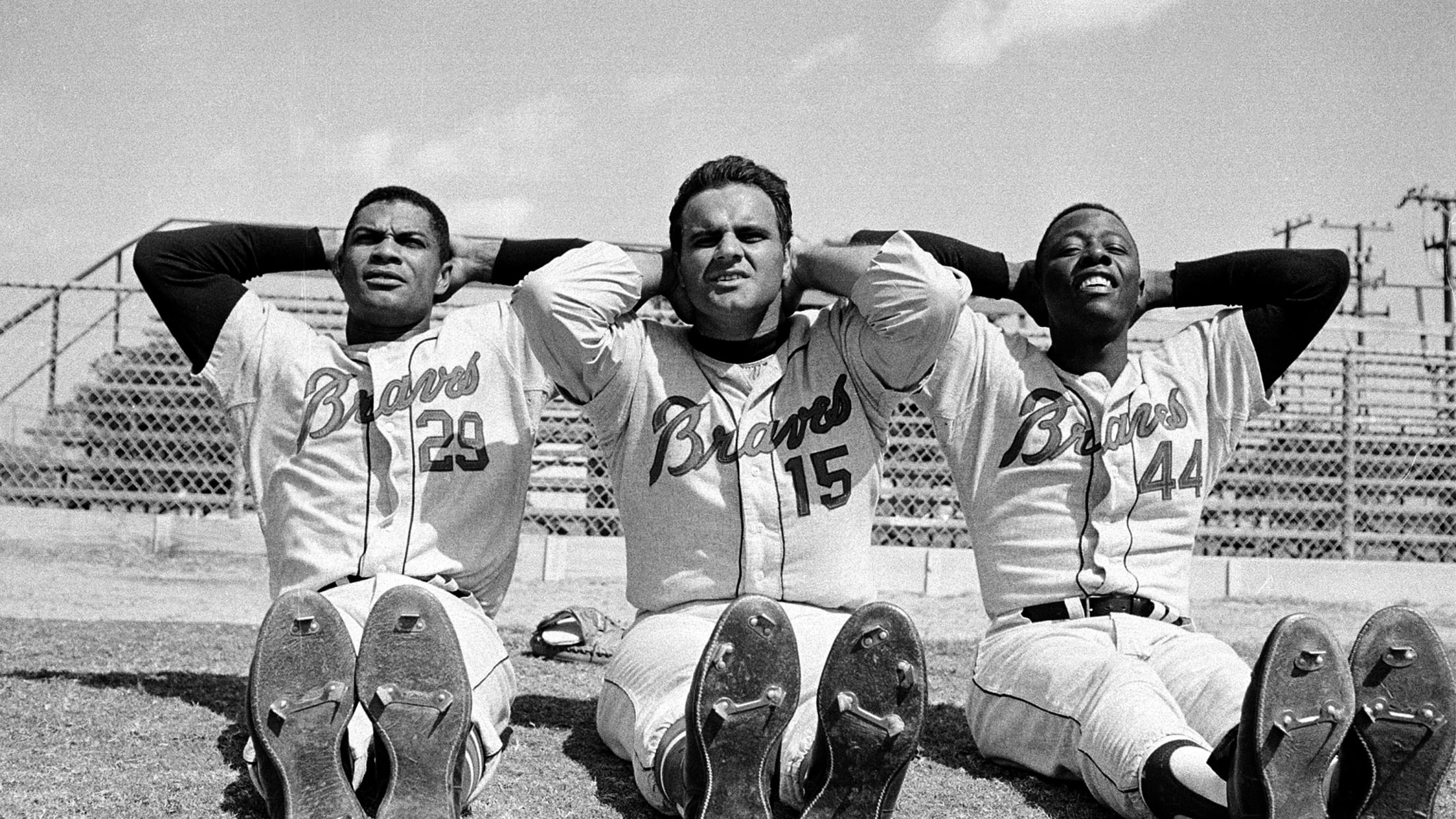

Their time as teammates was ultimately fleeting: The Giants traded Felipe to the Milwaukee Braves on Dec. 3, 1963, as part of a seven-player deal. He would ultimately be the most successful of the brothers, hitting .286 across 17 Major League seasons with 206 home runs and 852 RBIs while being named to three All-Star teams.

Mateo, who had his name anglicized to Matty, played for the Giants until he was traded to the Pirates in December 1965. In 1966, Mateo hit .342 to claim the National League batting title, finishing 15 points ahead of Felipe, marking the only time in Major League history that two brothers finished first and second in a batting title race.

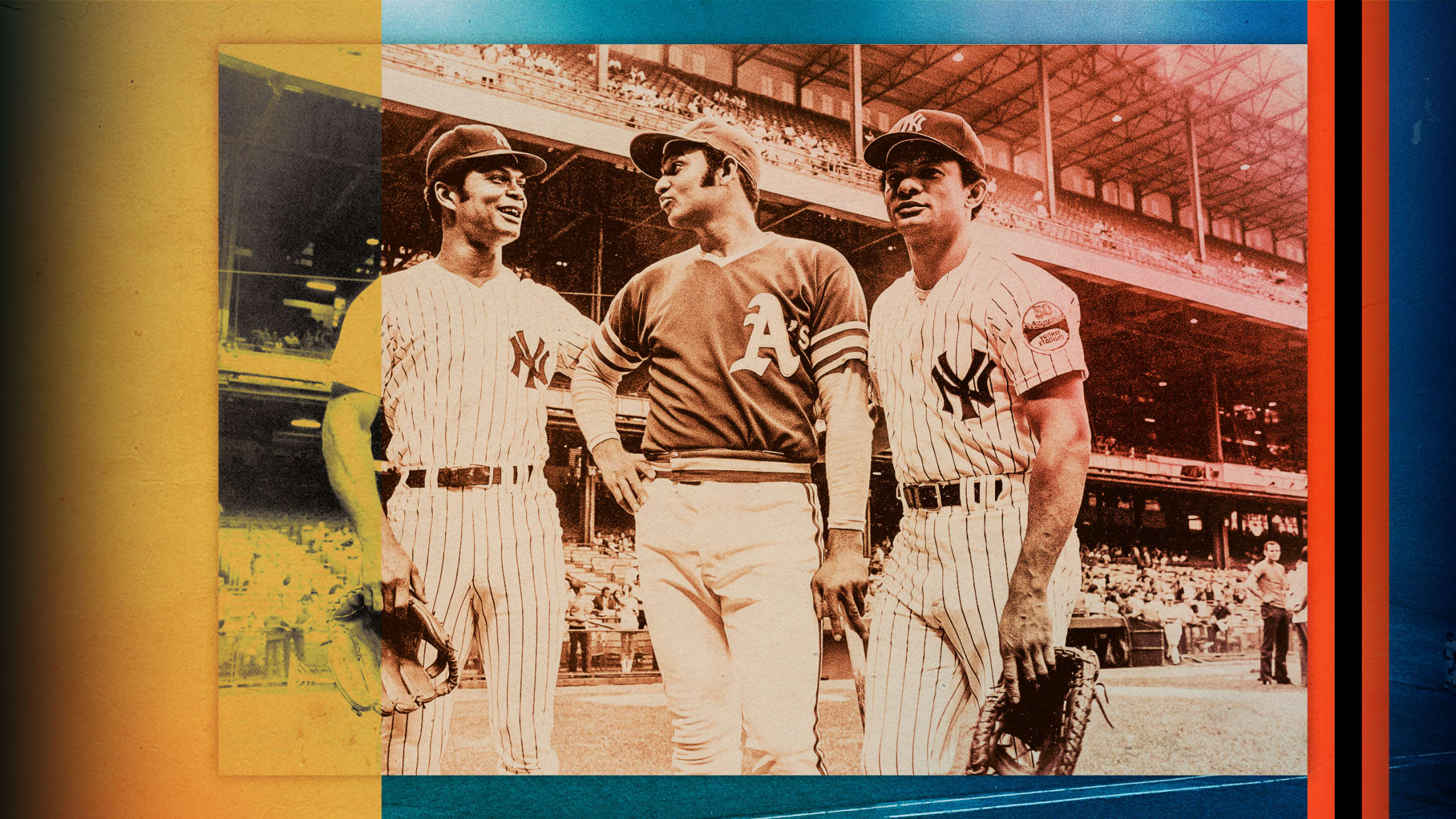

Jesús, known as Jay, originally signed with the Giants as a pitcher, but was converted into an outfielder like his brothers after an arm injury. He played for San Francisco from 1963-68. He also suited up for the Astros, Mets and Athletics during his 15 seasons in the Majors, winning back-to-back World Series in 1973 and ’74 with Oakland.

The Alou brothers notched a combined 5,094 hits in the Major Leagues -- the most of any other trio of brothers, ahead of the next group on the list, Vince, Joe and Dom DiMaggio, with 4,853.

Felipe made history again in 1992, becoming the first Dominican-born skipper in the Major Leagues when he took the helm with the Montreal Expos, a team he managed until 2001. He would go on to manage the Giants from 2003-06 and finished his managerial career with a 1,033-1021 record. Along with Frank Robinson and Joe Torre, he is one of only three men in baseball history with at least 2,000 hits and 200 home runs as a player and 1,000 wins as a manager. And in 1994, Felipe became the first Latin American-born skipper to be named Manager of the Year.

“For a young person like myself, growing up in the ’60s, as a young kid, [the Alou brothers] created a vision of hope that you could do that,” said Dominican-born executive Omar Minaya, who in 2002 made history of his own when he became the first Latino general manager in MLB history when he was hired by the Expos and later held that title with the Mets. He is currently part of the Yankees' front office as a senior advisor to baseball operations.

He adds, “When I think of them, I think of royalty.”

A lasting legacy

To date, 893 Dominican players have suited up in the Majors. The most recent, Cubs outfielder Alexander Canario, made his debut Sept. 6.

Today, the D.R. is a crucial pipeline of talent to the Majors, with each of the 30 clubs operating academies in the country. But when the first wave of Dominican players signed in the 1950s -- the Alou brothers, Marichal, Mota and Julian Javier, among others -- their success was not a guarantee.

“It was very tenuous. From the historical perspective of today, too often it seems like, ‘Of course, we were gonna get a pipeline from the Dominican Republic,’” says Burgos. “But that's not how history works. … People had to live the experience, they had to go through the challenges and overcome them, for this to happen.”

And the Alou brothers were also founders of one of baseball’s dynastic baseball families. Slugger Moises Alou was a six-time All-Star who hit .303 with 332 home runs in 17 seasons from 1990-2008. Mel Rojas, nephew of Felipe, Mateo and Jesús, was a reliever in the 1990s who pitched for the Expos, Cubs, Mets, Dodgers and Tigers. His son, Mel Rojas Jr., was the MVP of the Korea Baseball Organization (KBO) in 2020.

Now it’s Luis Rojas who carries the torch.

“Pride, a lot of pride, knowing he opened doors, not only for me directly as his son, but for many players and coaches,” said Rojas. “I carry that with a lot of pride, understanding the legacy of the family, the history of the family, and at the same time, a sense of responsibility to represent the country and Dominican culture.”

60 years later

As the 60th anniversary of the "all-Alou outfield" approached, Felipe Alou reflected on just how unlikely it is that the conditions that produced that outfield alignment would ever repeat themselves.

“You have to have three children, boys, to start,” he noted. “Three sons who play baseball. And three sons who have the talent level to play in the big leagues and, not only that, but with the same team. All that stands in the way of that record being matched.”

He also recognizes Mays’ willingness to come out of the game on Sept. 15, 1963, which made the historic moment possible. “I know Willie Mays enjoyed it,” he said. “It was a great gesture on his part.”

Felipe expressed sadness, too, that he is marking the anniversary without his brothers: Mateo passed away in 2011 at the age of 72, Jesús on March 10 of this year at the age of 80. “I would have liked for us to have been together 60 years later, like we were that day,” said Felipe.

In August 1975, as a member of the Mets, Jesús echoed his older brother’s sentiment that the outfield alignment had not been a big deal to the trio. He is quoted in The New York Times as saying, “We didn’t telephone home or anything. After all, we played together all the time in winter ball back in the Caribbean.”

Yet six decades of baseball have changed Felipe’s perception of the historic moment: “Now, it's huge, and history has made it bigger.”