Cal Ripken and The Streak, 25 Years Later

Can it be? Was it 25 years ago that Cal Ripken, Jr. broke the unbreakable record, playing in his 2,131st consecutive game to break the streak set by the Iron Horse, the immortal Lou Gehrig?

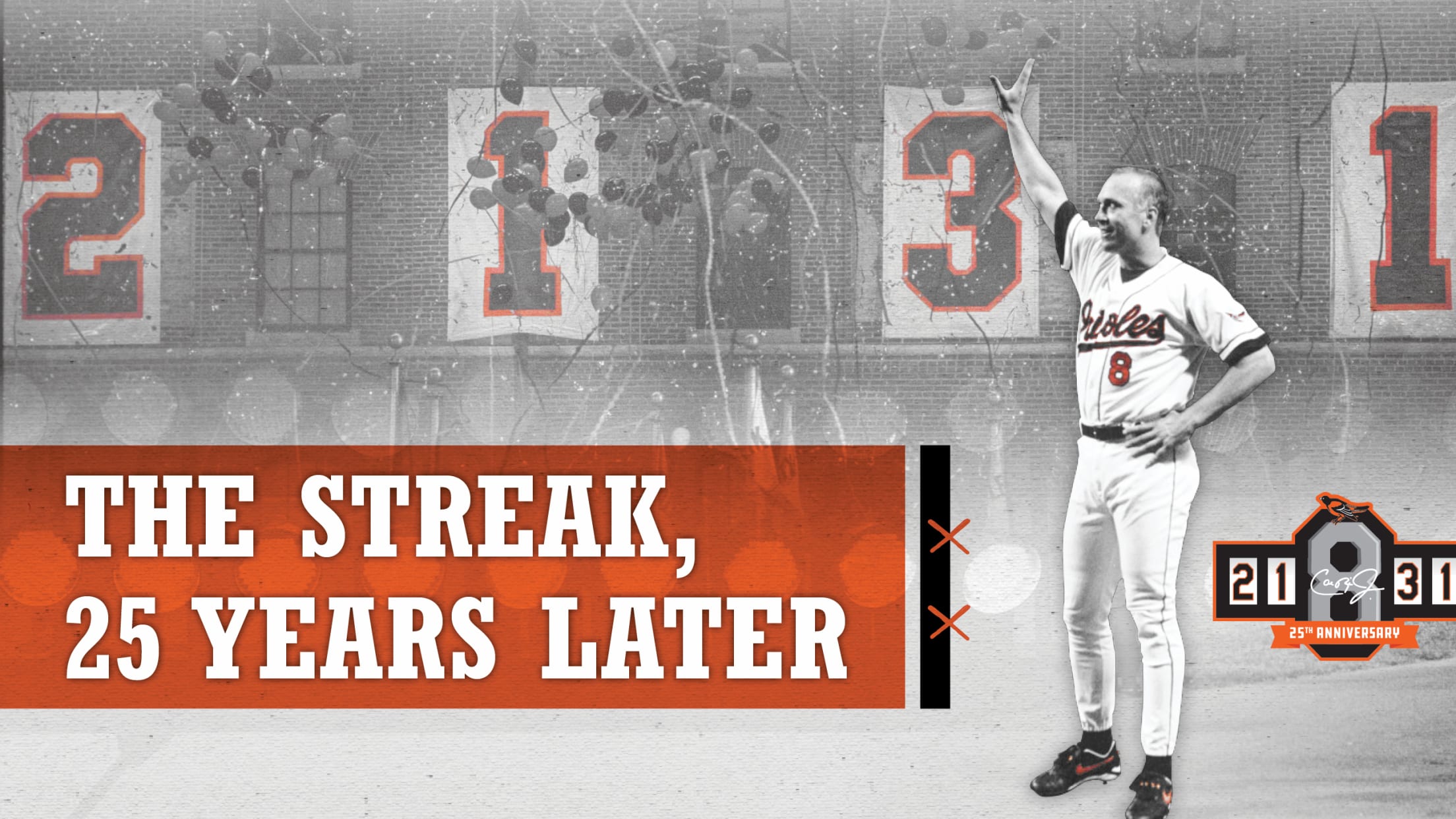

Anyone who was there -- or who watched it on local or national television -- will never forget the night of Sept. 6, 1995, when the Orioles game against the Angels became official in the fifth inning. The game stopped. The numbers dropped on the warehouse wall. Ripken acknowledged his family and the crowd and, with the fans still clamoring for more, finally was pushed from the dugout by teammates Rafael Palmeiro and Bobby Bonilla for his now famous lap around Camden Yards.

In Major League history, only seven players have had streaks of 1,000 games or more. Only 29 players have even racked up a streak of 500-or-more games (Pete Rose did it twice, the longest at 745 games). Ripken’s mark is more than twice as long as the National League record of 1,207 consecutive games by Steve Garvey.

Twenty-five years later, the longest active consecutive game streak by a current player doesn’t even stretch two full seasons. Kansas City’s Whit Merrifield, at 284 games, would have to play every game into the early part of the 2032 season to surpass Gehrig … at which point he would be 43 years old. In the last two seasons, only 12 Major League players played all of their team’s games in a single season -- and none did so in both years.

Which makes it even more remarkable that once Ripken passed Gehrig, he played another 501 consecutive games, ending the streak at 2,632 on Sept. 20, 1998.

Despite Ripken’s final total, the number “2131” and the date of Sept. 6, 1995, will always remain among the most significant in baseball history. It is a number frozen in time, and a number for all time.

The 1995 season began late because of the work stoppage that had caused the cancellation of the World Series the previous season, with a revised and shortened 144-game schedule. Ripken began the season having played in 2,009 straight games, 121 short of Gehrig’s mark. The date of Sept. 6 -- an Orioles home game against the Angels -- was circled on the calendar as the game he would break the record.

That is, if all went according to plan.

Wednesday, Sept. 6 was the final game of a 10-game homestand for the Orioles, meaning any postponement along the way which was not made up would push the record-breaking game to the next series -- in Cleveland. (In April, the Orioles were rebuffed by the Indians in an attempt to flip-flop home dates in order to give them some “breathing room” in the event of a rain out; the Indians saw the potential record-breaking game as a boost for their home crowds.)

The games of Sept. 5 and 6 had quickly sold out once tickets went on sale, and as the Orioles’ front office staff -- marketing and promotions, sales, public relations, Orioles Productions and others -- made plans to celebrate the nights the record would be tied and broken, they also wanted to build momentum along the way.

On the night of Aug. 14, after the Orioles returned from a road trip, fans at Camden Yards saw banners with the numbers “2-1-0-8” suspended on the warehouse wall, signifying where Ripken’s streak stood. The Orioles trailed the Indians in the fifth inning that night, so when the game became official at the end of that inning, the strains of “All I Need Is a Couple Days Off” by Huey Lewis and The News began playing, and, with little fanfare, the last banner changed from an “8” to a “9” -- raising Ripken’s streak to 2,109 games. Ripken trotted out to shortstop to take some grounders before the start of the sixth inning to a smattering of applause. The “moment” had gone virtually unnoticed by a sellout crowd of 47,198.

The next night, with the fans and media now grasping the significance of the banners, there was more applause when the Orioles left the field leading the Indians after the top of the fifth. Only this time, a new piece of music -- John Tesh’s instrumental, “Day One” -- played over the ballpark’s PA system, and with the perfect timing of the song’s crescendo ending, the number on the warehouse wall changed to “2-1-1-0.” Ripken emerged from the dugout -- as the inning’s leadoff hitter -- to a standing ovation from another sellout crowd of 46,364 fans.

During the course of nine more home games over the next three weeks, the ritual was the same with one difference: the Orioles were either tied or trailing after 4 1/2 innings, meaning they would have to bat in the fifth inning before the game became official. Which also meant Ripken would have to take the field for the top of the sixth inning while the numbers on the warehouse changed.

Each night, there was a long, standing ovation as the banners changed. Flashbulbs went off like fireflies around a remote campsite, with Ripken tipping his cap in between warmup grounders for several minutes. Now Ripken was in the middle of that campsite, standing alone at the back of the infield, with all eyes in the ballpark on him. The scene was shown nightly at the top of ESPN’s SportsCenter.

And then came Sept. 5, when Gehrig, the Yankees’ legendary first baseman, was caught and passed. For the first time since the second night of the banner’s dropping, the Orioles held the lead going into the bottom of the fifth inning. The game was official, so now, with the numbers on the warehouse about to change, Ripken could catch his breath, take it all in, and acknowledge the fans and his teammates from the dugout.

With Ripken on the precipice of breaking Gehrig’s mark, the scene repeated itself on Sept. 6. The Orioles held a 3-1 lead after 4 1/2 innings. This time, the game would stop for nearly 30 minutes in celebration of a man who simply came to work every day for 13 years and never took a day off, no matter how badly he was dinged up, no matter who was on the mound for the opposition.

That Ripken homered in both the 2,130th and 2,131st games was poetic. That he began his epic lap around the ballpark at precisely 9:31 pm -- which in military and Greenwich Mean Time is shown as 21:31 -- was even more so.

And it all started over one simple desire: to be able to be counted on by teammates, day in and day out. “I never set out to make history,” Ripken once said. The Streak, he says, is a byproduct of his desire to play and to be one of the players his manager felt should be in the lineup on any given night to give the Orioles their best chance to win.

“What it really signifies is that you were able to play a long time and play pretty well,” he said in spring 1999.

More than 16 years after Earl Weaver penned his name into the lineup on May 30, 1982, to unwittingly start The Streak, Cal Ripken did what only he could do -- take himself out of the lineup.

“When I look back, I feel very proud,” he said the night he sat down. “Not necessarily of the number of the streak but the fact that my teammates could always depend on me to be out there. The significance of the streak is not so much a number, but a sense of pride that this is my job and I went about it the way I thought I should.”

“So often, players are knocked for sitting out games,” Ripken said. “I always thought if you were able to play, that was what you were supposed to do.”

Playing every day was, to quote the title of his autobiography, “The Only Way I Know.”

In fact, Ripken had never watched an entire replay of Game 2,131 until this spring, when ESPN aired it as part of its “MLB Encore” series. In a pair of radio interviews earlier this year, Ripken talked for the first time about the lap around the ballpark, when Palmeiro and Bonilla forced him from the dugout.

“Rafael’s logic was, ‘Look, this game’s not going to get started unless you run around the ballpark.’ I was like, ‘I’m not doing that. I’m not doing that.’ I don’t know if you could read my lips, but I might’ve said, ‘That’s a dumb idea,’” Ripken told The Sports Junkies on Washington’s WJFK-FM. “It turned out to be not so dumb.”

On Washington’s ESPN 630, he said, “I ran down the [first-base line] and I started shaking hand, thinking, ‘OK, this is going to be a quick lap.’ As you start to get into it, the celebration turned from a large group of 40-some-thousand people to a very small, intimate experience where you’re looking into other people’s eyes. You’re recognizing names. I don’t know when it turned, but probably out (near) the outfield, the fence, I was thinking: ‘I don’t care if this game ever starts again. This is too cool.’”

Twenty-five years after setting a record that was 13 years in the making, it still is a moment for all time.

THE WORLD RECORD

One year after breaking Gehrig’s record, Ripken passed the world record of 2,215 straight games played by Japan’s Sachio Kinugasa from 1970-87. Kinugasa traveled from Japan to Kansas City to be present when Ripken passed his mark. Later that night, the two players with the longest streaks of all-time found themselves at the same Kansas City brew pub, and after finishing eating, pulled their tables together and conversed for more than an hour over beers, with several Orioles teammates and staff posing as flies on the wall, listening in.

Kinugasa, who died in 2018 at age 71, was a third baseman for the Hiroshima Carp who earned the nickname “Tetsujini” -- Iron Man. Unlike Ripken, Kinugasa’s streak was still intact when he retired after the 1987 season.