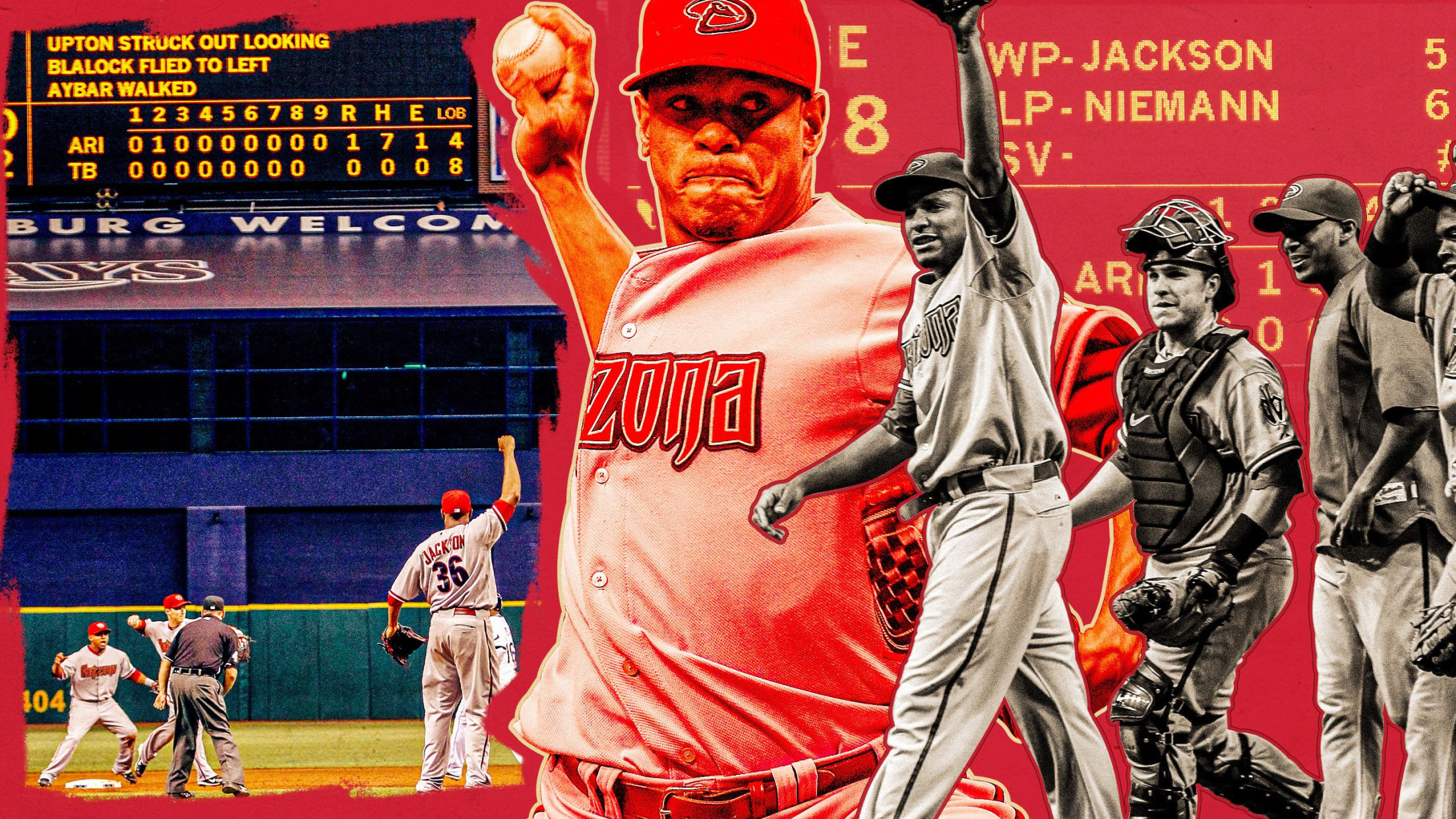

Reliving Jackson's 149-pitch no-no 15 years later

Initially, Miguel Montero couldn’t figure out what they were talking about.

It was June 25, 2010, and Montero was preparing for another inning behind the plate. He saw Arizona Diamondbacks manager AJ Hinch speaking with an assistant general manager in the visitors' dugout, and for some reason, the assistant GM was telling the rookie manager not to worry about Edwin Jackson’s pitch count.

Why, though? What would make this game different? Montero searched the scoreboard for answers.

“I look up, and it’s zero, zero, zero,” Montero said. “What the heck? I’m like, ‘He’s throwing a no-hitter!’”

So Jackson stayed in the game. At the end of the night, the Tropicana Field scoreboard still showed zero, zero, zero, followed by a “9” – nine runners left on base by the Rays. Jackson walked eight batters and hit another, and one hitter reached on an error. He threw 149 pitches, still the highest single-game total since 2005.

Jackson, an admirably resilient man with an extraordinarily durable arm, pitched through it all to complete one of the strangest no-hitters in Major League history.

It was a night that Jackson, then a popular young pitcher and now a 17-year veteran who’s played for 14 teams, describes as being full of “the good, the bad, the ugly, the crazy, the bizarre and, to finish up, the unique.” What follows is the story of that game, told 10 years later by those who took part in it.

(Note: All people are listed with their team and position/title at the time.)

A wild start

Edwin Jackson, D-backs starting pitcher: We had an off-day before, and I feel like with off-days, you never know how you’re going to feel the next day. Especially if you don’t come in to play catch, it’s like 50-50. I didn’t come in to play catch the day before. You feel it instantly when your arm slot is off.

Mel Stottlemyre Jr., D-backs pitching coach: As a pitching coach, you see all kinds of things in bullpens and you try to never show any panic to your players. But he was struggling to find the zone.

Jackson: As a starter, you just keep throwing. Warming up is warming up. But in my mind, I was like, “OK, it’s a possibility it’s going to be a long short day.” I know it’s an oxymoron, but the short games you have, you’re in the locker room a long time watching.

Stottlemyre: The stuff at the end of his pitches, it was fairly electric that day. So his bullpen wasn’t the greatest, and I do remember that. He probably wouldn’t remember that, but I do. But the stuff was really good.

Rays starter Jeff Niemann worked around two walks in the first inning by getting three outs on a pair of ground balls. Jackson, who pitched for Tampa Bay’s American League championship club in 2008, scaled the mound before a modest Friday night crowd of 18,918. Knowing Jackson’s erratic tendencies, the Rays stuck to their game plan and took 22 of his 27 pitches in the first inning.

Joe Maddon, Rays manager: Make him throw strikes and come after you, because he would do that. Early in the game, that’s when you wanted to get him. Because if he were to settle in and get to the seventh inning, he’s still throwing 95-99 mph with more confidence. … My experience was the deeper he got, the better he got.

Stottlemyre: Pitching coaches start getting nervous when guys get to 25-30 pitches in an inning, especially with traffic. You have to start saying to yourself, “Is he going to get through the inning?”

After a pair of walks and a wild pitch, the Rays had runners on the corners with two outs in the first. Matt Joyce grounded out, and Jackson was out of the inning. He walked B.J. Upton and Jason Bartlett in a 19-pitch second inning, but again, the Rays -- whose offensive mantra that season was GTMI (Get The Man In) -- couldn’t get a man in.

Derek Shelton, Rays hitting coach: That team was built -- and Joe used to talk about this -- to walk, strike out and hit homers. We had a lot of guys that did those things, and I think as you saw, we were very patient. … We got ourselves into a lot of good situations. We just did not capitalize on it.

Dewayne Staats, Rays broadcaster: It occurred to me that all of Edwin’s wildness might have been his greatest asset in throwing that no-hitter. No one was digging in to begin with, and I’m not sure if they were thinking in patterns or pitch location or where the next pitch was going to be. No one, including Edwin, was really certain of that.

B.J. Upton, Rays center fielder: I feel like we had him on the ropes a lot. Just when you thought he was going to lose it, it was like he hit another gear. And he kept getting out of jam after jam after jam.

Jackson: Man, I had a slider. That was my savior. The fastball command was everywhere, but my slider.

Dontrelle Willis, D-backs pitcher: Every inning, he would come into the dugout -- he was dodging bullets here and there, mishaps here and there -- and I was like his corner man, hyping him up. That’s kind of weird, because usually you leave the starting pitcher alone. But we had such a good relationship that it was just normal. He was coming to me like a fighter after a round, and I was toweling him off and talking to him, reassuring him, “Hey, you’re nasty, bro. You’re dirty, bro. They can’t hit you. Just make pitches when you have to.”

The third inning looked like the breaking point. Jackson walked Ben Zobrist, Evan Longoria and Carlos Pena in order, giving him seven walks and six outs recorded on the night, and Arizona reliever Esmerling Vasquez started throwing in the bullpen. Jackson threw 22 pitches in the third, and only eight were strikes, but he danced out of trouble.

Shelton: Our approach wasn’t bad, because we put ourselves in situations to score runs. We just didn’t get hits.

Staats: Think about how difficult this is for a hitter. If you have a pitcher who, for a series of pitches, can pinpoint with the idea of overpowering you -- and then at the same time, at the end of that little stretch, he’s going to miss completely on the other side of the plate and up or down from where he wanted to be -- that makes it really problematic for a hitter.

Miguel Montero, D-backs catcher: At that point, I didn’t even know he was throwing a no-hitter. So I want him to throw strikes and get quick outs. But he still wasn’t capable of doing that. So like, get an out, get an out. We’ve got guys in the bullpen [warming up over and over] left and right: get up, get down, get up, get down. There were so many batters we faced in three innings that I really don’t remember. All I remember is a couple good plays here, a couple good plays there and we got out of jams.

Jackson: I stayed a hit away from being out of that game literally from the third inning on.

Willis: Every time a ball was in play, guys were diving all over the place and making plays. It was a real credit to the ballclub. They wanted it for him, and that’s the type of guy he was. He’s played for 392 teams, and you’ve never heard one bad word about him.

Jackson: A lot of people were like, “Man, we thought for sure we were going to get four or five off you.” And I was like, “I did, too. But I just kept throwing.” I mean, I walked the bases loaded. Most times, you walk the bases loaded and you’re giving up at least two of those runs -- at least two. That’s two sac flies. But man, somehow I Houdini’d my way out of there.

Cruise control

In three innings, Jackson threw 68 pitches, only 30 of them for strikes. But Adam LaRoche’s second-inning homer off Niemann gave him a lead, and when Jackson returned for the fourth, he rediscovered his arm slot and some semblance of fastball command. He needed only 10 pitches to retire Sean Rodriguez, Bartlett and John Jaso in order, his first clean inning of the night.

Jackson: I found my rhythm. You can feel it as soon as you’re warming up, like, “There it is.” Once that clicked, I was able to lock in and continue to throw the offspeed, which alone had gotten me to where I was in the game, period. I was able to add fastball command to that and continue to keep the repertoire sharp enough for me to enable them to hit balls at people.

Shelton: I think when he went out in the fourth and his stuff started to get a little sharper, that was where it was like, “Oh, here we go. We’ve had our opportunities, and we haven’t scored. Did we miss it?” Not that we thought we were going to get no-hit.

LaRoche: It didn’t really cross anybody’s mind that it was a no-hitter until really late in the game. You look up at the scoreboard expecting a couple hits or whatever, but you look up and see a zero. It was a little odd.

Jackson: It was so much traffic that umpires and coaches forgot I had a no-hitter going on. [Rays first-base coach] George Hendrick, he told me he and the umpire were on first base like, “Why is this kid still in the game?” Then they looked up at the board like, “Oh, damn. He’s got a no-hitter going on.”

Willis: Midgame, I remember he was like, “Man, I just don’t know what’s going on.” I was like, “It doesn’t matter what’s going on! They can’t hit you!”

For these Rays, it always seemed to be a possibility. About seven weeks earlier, Dallas Braden pitched a perfect game against them in Oakland. On July 23, 2009, Mark Buehrle threw a perfect game against them in Chicago. Three years later, they were on the wrong end of a perfect game by Felix Hernandez in Seattle. The Rays won the American League East in 2010, yet they were no-hit twice within the span of two months.

Maddon: I don’t know how that plays out historically, but if you are a big punchout team and not putting the ball in play as often, that would play into that. And as a high-walk team, you’re taking pitches and you’re willing to take a borderline full-count or 2-2 pitch because that’s who you are, as opposed to trying to dump it in the opposite field. For me, a high-punchout, high-walk team would have that opportunity to get no-hit. We got perfect-gamed. We got everything.

Upton: We just had a knack for getting no-hit. It really became a running joke.

Shelton: We had stretches of guys that could be attacked with the same out pitches and same game plans. I think that’s something that we learned from that year. … You take the good with the bad. I would definitely take [96] wins with that club.

Jackson breezed through the fifth inning on nine pitches. He hit Upton, one of his closest friends on the Rays, but otherwise avoided trouble in an 11-pitch sixth inning. Unlikely as it may have seemed, he cruised into the seventh inning with a shutout and a no-hitter intact. But having thrown 98 pitches, he was about to make life stressful for his manager and pitching coach.

Talking through it

After a swinging bunt rolled foul down the third-base line, Bartlett finished a seven-pitch at-bat in the seventh inning by lining out to Mark Reynolds at third base. In Arizona’s bullpen, reliever Sam Demel warmed up as Jackson crossed the 100-pitch threshold. Jackson needed four pitches to retire Jaso and another eight to get through Zobrist.

“He’s nearing the end,” Rays broadcaster Kevin Kennedy said before Zobrist flied out to center, “and he knows it.”

Jackson: After the seventh inning, I had already pitched about 10 innings probably. I don’t argue with managers. I don’t step on anyone’s toes or anything. I’m super respectful. But I was like, “AJ, I ain’t coming out of this game until I give up a hit.”

Carlos Pena, Rays first baseman: The one thing I recall is that he was militant and he was resilient, because it didn’t look like he was breezing through the lineup. It’s the seventh inning and we’re like, “Wow, he’s still in there.”

Montero: I was thinking about, “When are they going to take him out?” Because I didn’t know it was a no-hitter going on. I knew he had 100-something pitches already. I’m like, “They’re going to break this guy right here.”

Willis: Guys are in the bullpen warming up, trying to fill the game, because it’s like, man, this could get hairy. Credit to AJ for keeping him in the game and understanding, like, “Hey man, he has a chance to do something historic.”

Pena: You get the sense that, OK, we’re going to knock this guy out early -- whoever you’re facing -- if you get going in the first few innings. That was the feeling we got in the first inning. And certainly by the third. So you can only imagine when the seventh inning came around, like, what in the world is going on?

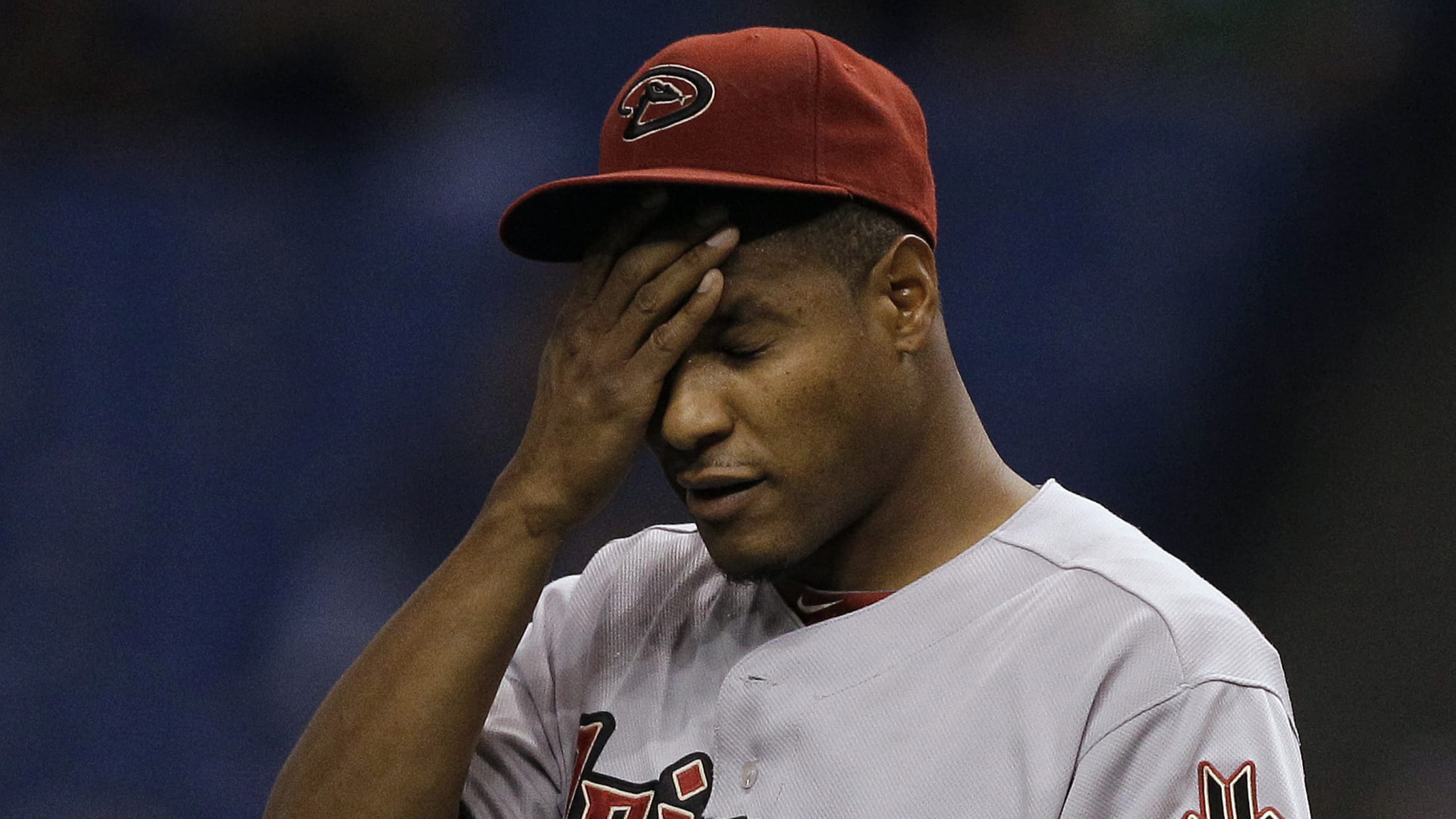

Stottlemyre: I’m going to tell you, from a guy that had a bunch of shoulder surgeries and fought injuries my entire career, I’m always very sensitive to thresholds, recovery and just not wanting to push past that point. I don’t believe in babying guys, but I was uneasy that day.

Maddon: I’m thinking to myself [Hinch is] just hoping so badly that we get a hit, because that takes so much off of his plate right there. I’m glad I don’t have to deal with it and am wondering what he’s going to do. The way front offices are thinking these days, normally that’s not going to play well. That’s why you should have a no-hitter meeting in advance with everybody on board to conclude exactly how you’re going to deal with it.

Stottlemyre: If it was somebody different that had a harder delivery with more crossfire and wasn’t quite as resilient, didn’t recover this quick, then the decision would have been made long before the ninth inning that that player wouldn’t have been allowed to go.

LaRoche: Edwin wasn’t coming out anyway, I’m pretty sure. I don’t know that it was AJ's decision at that point.

Stottlemyre: [Jackson] said, “I am not coming out. Let me go. I’ll skip the next game. I’ll use an extra day. Whatever. But I’m not coming out of the game.”

Upton: I knew he wasn’t coming out. He was still throwing 97! There’s no chance.

Stottlemyre: It was AJ's first year managing, and I was a first-year Major League pitching coach. So there was a lot on our shoulders. I can tell you, there was a nervousness that went with our decision -- something I’d never really experienced. In the coaching world, you always feel like you know what’s right. And I couldn’t tell you that day that that was doing the best thing for the player, other than that there was going to be a fight in the dugout if we took him out.

Jackson: It was super unorthodox. I’m talking to the manager. I’m talking to the pitching coach. I’m talking to everyone the whole damn game. It’s not like it’s one of those no-hitters where everything is smooth sailing and no one is talking to you. It’s so chaotic and so hectic with people on and off the bases, I was talking the whole game. Yeah, we talked our way through a no-hitter.

Stottlemyre: I hate to say this, and I would hate for E.J. to know that I was even remotely thinking this, but I’m not kidding you: When he got into the 120s, I was pulling for a hit. That’s terrible, but I was that uncomfortable.

Meanwhile, Jackson kept making pitches. Pena reached on an error by Stephen Drew with one out in the eighth, and the Rays sent speedy outfielder Carl Crawford to pinch-run at first base. Jackson got Joyce to fly out, bringing up Upton. After two pickoff attempts and two sliders, Jackson’s 133rd and 134th pitches, Crawford tried to steal second. Montero cut him down to end the inning.

Jackson: That was a big out right there. Carl Crawford doesn’t get thrown out a lot. And it was on a slider, too.

Upton: That’s one of those things in baseball where you’re like, all right, stars are aligned. It was rare for Carl to get thrown out. It had to be the perfect pitch. It had to be the perfect throw. And it was.

Jackson: I think C.C. would like to argue he was safe at second.

Montero: And you know what? If you look it up now, with the replays and stuff, he probably was safe. You know? It was a perfect throw. Everything was perfect. It was a bang-bang play. I really don’t know if he was safe, if he was out. They called him out, so I’m good with that. I’ll live with that.

Jackson still remembers every big defensive play that night. Ten years later, he’ll name every player in the D-backs' lineup when asked how he got through the game. He returned for the ninth inning to strike out Upton and retire Hank Blalock, bringing up pinch-hitter Willy Aybar with one out standing between him and history.

Montero: Adrian [Johnson] was the umpire. He wasn’t squeezing, but borderline pitches could’ve been called strikes, especially in the situation, you know? He called a ball and I turned around -- honestly, like, I could’ve jinxed it right there -- and I told him, “Hey, do you know what’s going on out here? I need you to open up a little bit right now!” He was aware. He goes, “Yeah, I know what’s going on.” [Heck], man, help him out a little bit.

Stottlemyre: I remember him walking a guy in the last inning. I remember AJ Hinch telling me, "Last guy. Last guy. Last guy." We were very uneasy, and he had a two-out walk.

Jackson’s eighth and final walk brought up Bartlett, who took one pitch and fouled off another before hitting a grounder to Drew at shortstop.

Willis: Stephen Drew gets the ball and double-taps it, so I’m like, “Throw the effing ball!” He wanted to give himself a little bit of time. But they could have called interference on me, because I swear, I was already 10 steps onto the field. Like, “Stephen, just throw it!” And there was someone on first, so I thought he was going to go the easy route. But when he threw it [to LaRoche at first base], I was like, “Noooo-yes!” That final out, I will never forget. Just get this over with, because I didn’t want another batter to get a chance to spoil it for him.

Jackson: It was disbelief, like, “Damn, I just did this! I just did this! I really just threw a no-hitter! I escaped all the trouble I had, walking the bases loaded, and threw a no-hitter.”

Staats: I think I’ve called nine no-hitters in my career, and that one was -- by far -- the most bizarre no-hitter I think I’ve seen. And it was thrown by one of my favorite guys in the game.

Maddon: It was such an unlikely no-hitter. It just didn’t make any sense. But Edwin had a tendency to get better as the game was in progress, and he’s as good of an athlete as anybody in the game in terms of strength and how his arm works. His velocity normally seemed to get better. If anybody was going to be able to pull it off, it was going to be him.

Jackson: After that, man, the hard work is done. You get to scream like a little kid out there, like it’s the Little League World Series, and jump up and down on the mound. To this day, I talk about it and I just laugh. Like, "Bro, how did you throw 149 pitches?" "Man, I don’t know."

Willis: He was so overjoyed. For anybody that throws a no-hitter, man, that’s your legacy. That’s for all time, regardless of how your career ends up. You’re immortal. That’s how I took it when he did it. Bro, this is one for the books. And this is my best friend getting a chance to do this.

Something to celebrate

On the field, Jackson received a shaving-cream pie to the face from his teammates and a round of applause from Tampa Bay fans showing their appreciation for his time with the Rays and his 149-pitch effort. While stadium staff prepared Tropicana Field for a postgame concert by Tantric, the D-backs celebrated inside the visitors' clubhouse like they’d just clinched a playoff spot.

Jackson: It was crazy. It was fun. It was like a mini-playoff game [celebration] in the clubhouse, especially for a team that had been scuffling that year. It was great for us to finally have that much fun for something. We needed that.

Montero: AJ Hinch called me to the office and he said, “Hey, are you going to go celebrate with Edwin or do you want to play tomorrow?” And I remember asking, “Who’s pitching tomorrow?” He’s like, “David Price.” And I’m like, “No, I’m going to celebrate.”

Willis: It was just a crazy game, man. Even guys on the other team that he was friends with, because he was in Tampa, they were excited and happy for him. And we all went out after and hung out.

Montero: Even the opposing team got so happy for him that he threw a no-hitter. That tells you what kind of a guy he is.

Upton: You’ve got to understand: This isn’t a guy that we wanted to leave our ballclub. He helped us basically put the Rays on the map. If we don’t have that ‘08 season, what are we talking about? That was a guy that was close to us. It was more than just being a teammate for me. I had known him before he even became a Ray. To get to see him do it, it was bittersweet. I was very, very happy to see him come back and be like, “Yeah, this is what you missed out on.”

At least one person was still worried amid the revelry. The D-backs pushed Jackson’s next start back two days and only let him throw 88 pitches in that outing, but they wouldn’t feel like they were out of the woods until they knew he was healthy the next day.

Stottlemyre: In that instance, you’re still really kind of uneasy. I’m going to tell you, for a couple days, I stayed on eggshells because I knew 149 pitches was above and beyond anything that we would ask pitchers to do.

Jackson: I mean, I was a little hungover [the next day]. But aside from being hungover, my body felt good. I long-tossed the next day. I was good to go. Anything I felt was from festivities off the field.

Upton: I can’t say that I wasn’t with him. I’ll tell people that now. Couldn’t say that then.

Parting gifts

Arizona was 29-45 and less than a week away from firing Hinch and GM Josh Byrnes. A little more than a month later, the D-backs traded Jackson to the White Sox for David Holmberg and Daniel Hudson. Jackson took parts of that game with him. In his house in Arizona, he still has the pitching rubber from the mound that night, the lineup cards, some tickets and a number of game-used balls. One of the lineup cards came from Maddon.

Maddon: Every time I’ve been no-hit as a manager, I get the scorecard -- the wall card -- and I will write a little note and send it over to the other side. It happened so often that I got in the habit of doing that.

Jackson also delivered gifts of his own. Before the D-backs left town two days later, Jackson had copies made of the photo of him recording the last out. He signed one for every member of the Rays’ support staff: clubhouse managers, public relations officials and so on. He didn’t stop there.

Montero: I got a replica lineup card, authenticated. I think Edwin made one for each teammate. He was great. He made something for everybody.

About a month later, LaRoche received a watch from Jackson that his wife, Jennifer, found earlier this month. Engraved on the personalized timepiece: “6/25/10,” the date of the no-hitter LaRoche helped Jackson win.

LaRoche: He’s just one of those selfless guys. He deep down viewed it the other way, that he was totally lucky here and it was all because he had a great team. Just totally humble about that whole situation. No surprise. His whole career is like that.

Pena: For you to say, “Yeah, I threw a no-hitter in the Major Leagues,” that’s crazy to be able to tell your grandkids. Then he can say, “I threw one of the most unique no-hitters in the history of the game -- possibly the most unique no-hitter in the history of the game. I walked this many guys, threw this many pitches, everyone thought I should be coming out of that game.” That’s where the story gets cool, because now he can really say he walks the talk: “I didn’t give up.”

Jackson: You probably won’t see that many pitches again. [Tim] Lincecum went 148 one time [in 2013], and I was watching like, “Damn, he’s going to get it.” But nowadays, you probably won’t see that many pitches thrown again. You’ll see 115, 120ish, but you probably won’t see that many pitches again.

Willis: I can honestly tell you that, out of my whole career, it was probably in the top five coolest things I saw live.

Jackson: It’s definitely up there. It’s one of those things that can’t be taken away. People can say, “Oh, it’s an ugly no-hitter.” I look at it as, I just stacked the odds against me -- and I defied them.