The little-known story of an inspiring baseball upset

The 1945 Tucson Badgers were incredibly confident coming into their game on April 18, and why shouldn't they have been?

They were reigning, six-time high school state champions. They'd won 52 straight games. They were sending ace Lowell Bailey to the mound -- a senior who had a 0.00 ERA in 1944, just the fourth U.S. high school pitcher (up to that point) to finish a season without giving up any runs.

"He was a star pitcher," Joan Bailey, widow of Lowell, told me in a call. "He was really a big deal -- I mean, they all were. They were the state champions. Probably a little cocky."

But the Badgers may have underestimated who they were playing that day.

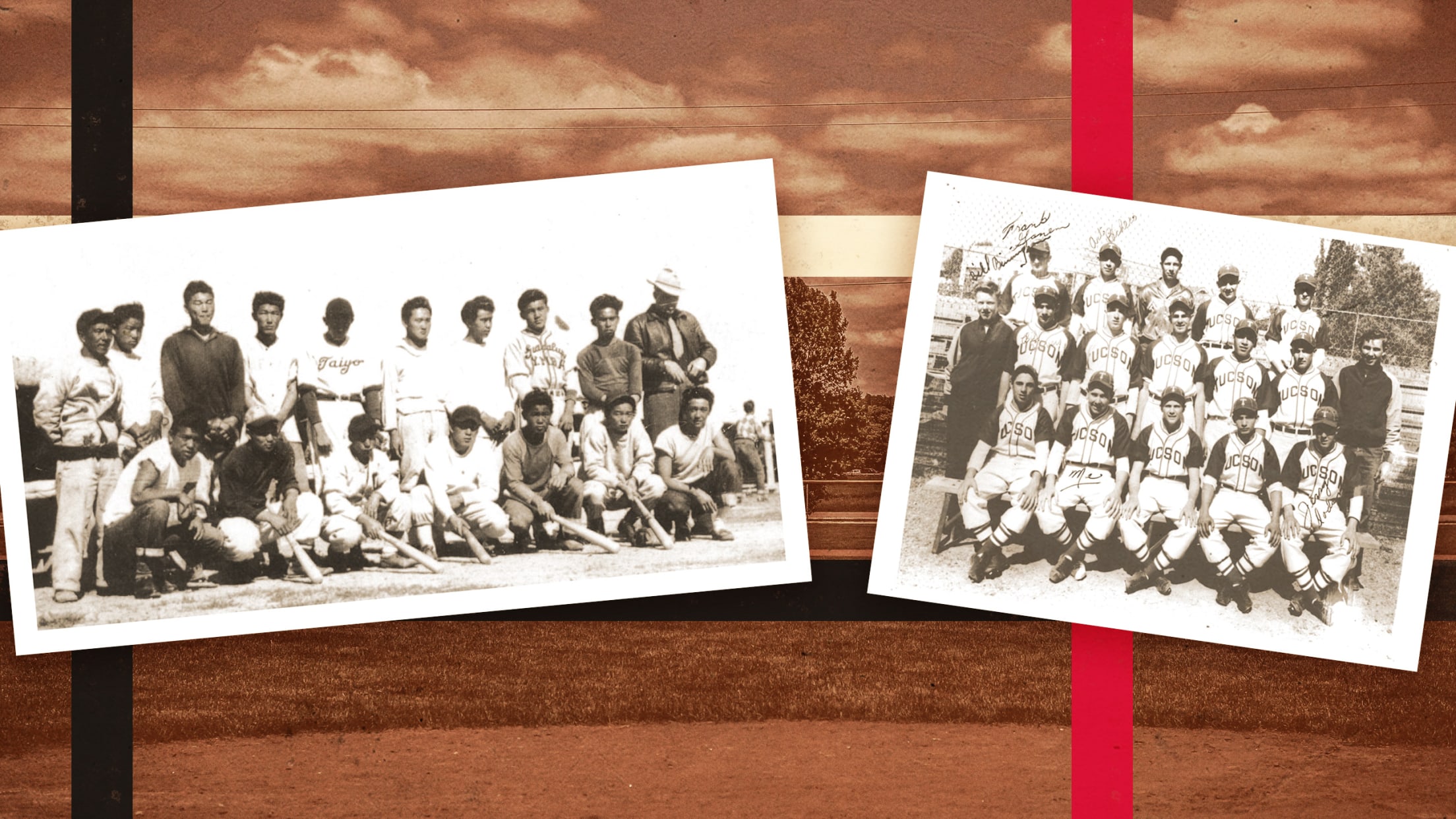

Their opponents were the Butte Eagles, a high school team that played at the Gila River Relocation Center -- one of 10 incarceration camps Japanese-Americans were forced into during World War II. They built and maintained their own fields, they installed seating, they took pride in playing America's pastime ... even when their lives in this country had been brutally uprooted.

"I look at it as kind of David versus Goliath," Kerry Yo Nakagawa, founder of the Nisei Baseball Research Project told me. "Here was this All-Star team inside an incarceration camp against this powerhouse Badgers team. It was almost like a Hollywood script."

More than 80 years ago, at the outset of World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066.

The law evicted nearly all Japanese-Americans from the West Coast -- they were deemed as threats to the country's security -- to incarceration camps. Families could take just two suitcases and had to sell off the rest of their belongings. The camps were decrepit, with tar paper-walled frame buildings, barbed wire and armed guards keeping a watchful eye. They were essentially prisons for these mostly U.S. citizens, from 1942-46.

But even after being ripped from their neighborhoods, after having their lives completely upturned, Japanese-American families attempted to transform their horrendous circumstances into new, working communities.

"Yeah, these were full communities that were essentially established overnight," Japanese baseball historian and author Bill Staples told me. "Phoenix and Tucson were the first and second largest cities in Arizona. Then these two Japanese-American camps [Gila River and Poston] were the fourth and third largest cities at the time. So yeah, they had schools, they had hospitals, they had councils that oversaw the community. They tried to recreate as much of their normal life as they could behind barbed wire."

And at Gila River, like at many camps around the country, another crucial part of their old lives was reestablished: Baseball. Lots of it.

"Baseball was first played in 1943 [in the camps]," Staples said. "That's when Zenimura Field opened up. The first two years, they had this 32-team league with divisions A, B and C."

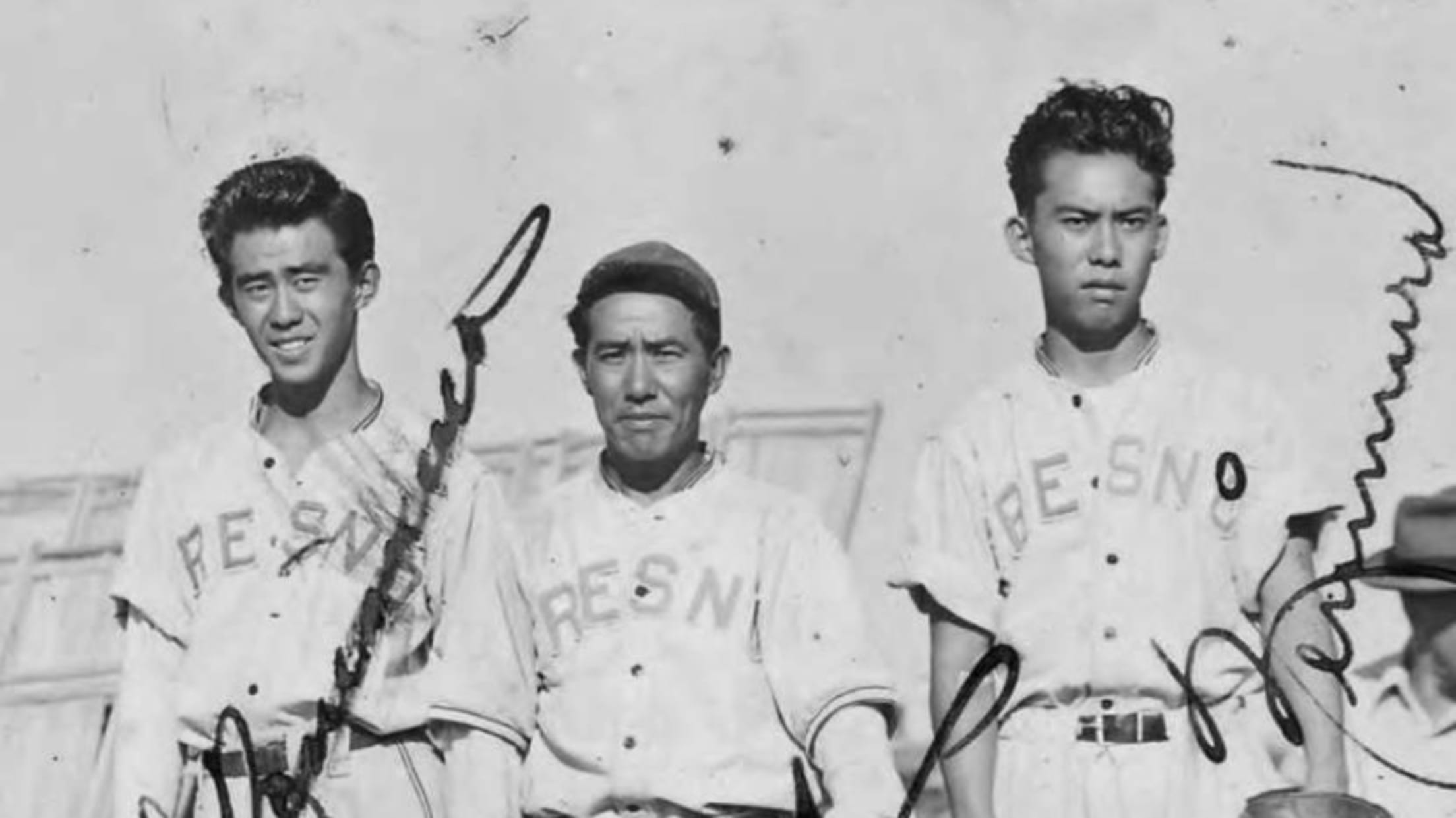

Kenichi Zenimura is known to many as the father of Japanese-American baseball. Born in Hiroshima, he grew up in Hawaii playing the game and then latched on to Japanese-American and previously all-white teams upon moving to Fresno, Calif. He was a fantastic player, but later became known for his influence and connections throughout the international baseball community. He was instrumental in organizing barnstorming tours to Japan that featured Negro League stars like Biz Mackey and Andy Cooper. He was also integral to getting Babe Ruth to visit and play in 1934.

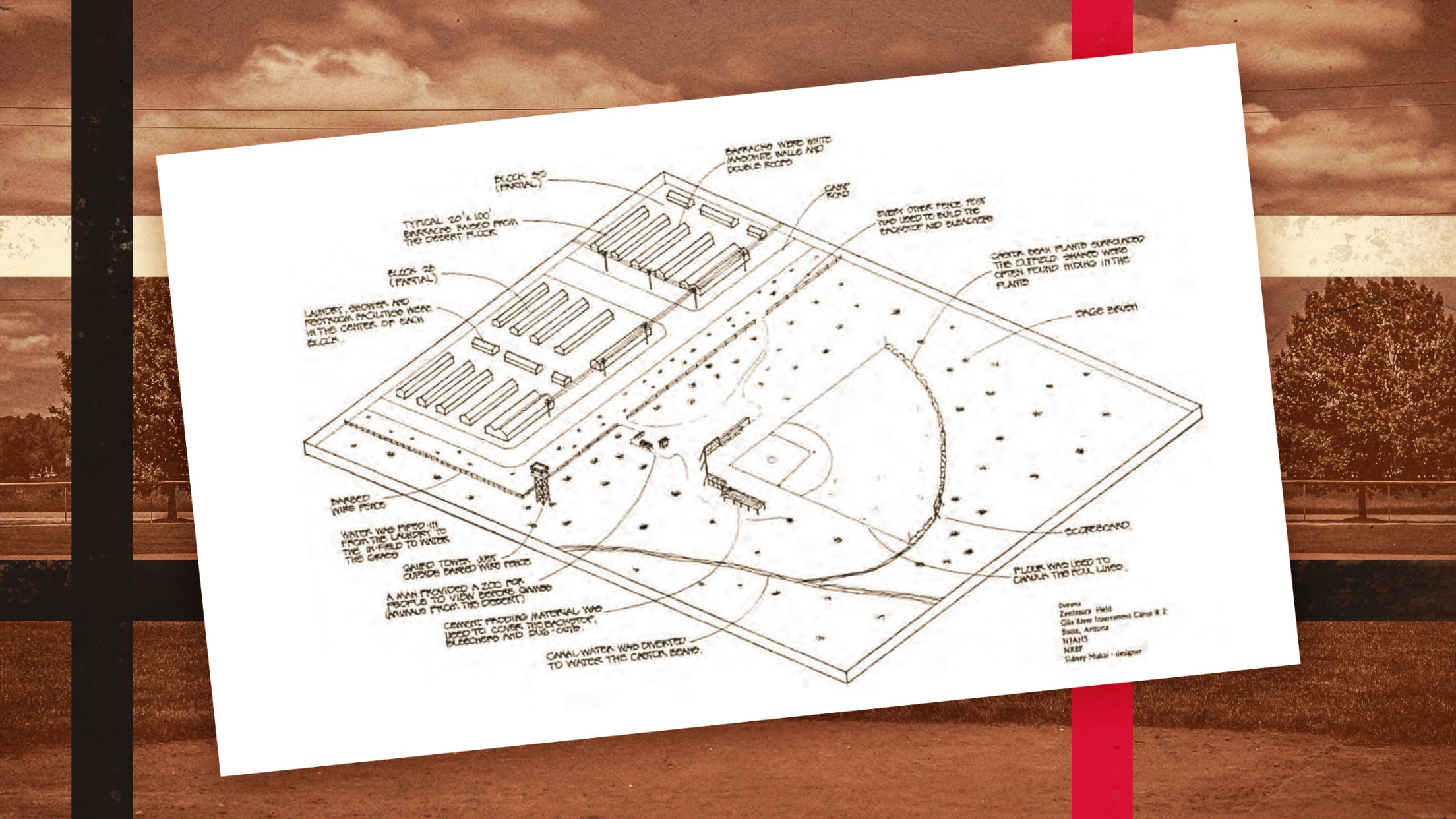

When Zenimura and his family became imprisoned at Gila River, he almost immediately set about building a baseball field with the blessing of the camp's director. It was located just outside the barbed wire that surrounded the barracks town.

They tried to recreate as much of their normal life as they could behind barbed wire.

According to Staples' book, "Kenichi Zenimura, Japanese American Baseball Pioneer," Zenimura just started cutting down sagebrush one day and clearing rocks with his bare hands. Others eventually came to help build what would become Zenimura Field with tractors and shovels. Zenimura would water the field every morning. Two other fields were added nearby.

Pat Morita, famously known as playing Mr. Miyagi in the Karate Kid films, was interned at Gila River with his family during this time. As noted in Staple's "Zenimura," the late actor remembered the Zenimuras' maddening effort to keep their field in shape.

“I remember watching this little old brown guy watering down the infield with this huge hose,” said Morita. “He used to have his kids dragging the infield and throwing out all the rocks. Jeez, I was glad I wasn’t them. They worked like mules.”

“Baseball was the only thing that kept us going," Kenichi's son, Kenzo, was quoted as saying in "Zenimura." "If we didn’t play baseball, camp life would’ve been unbearable. Even when we didn’t play, we were out there watching.”

Men of all ages and talents played in the various divisions at Gila River, while women played in softball leagues. Local high schools, semi-pro squads and barnstorming all-Black teams took on the Gila River teams -- some playing on the camp fields while others, if the county allowed, hosted Gila River at a diamond outside of Butte. Baseball supplies were brought in through arrangements with sporting goods companies like Spalding and, although uniforms became easier to get through fundraising, jerseys were difficult to come by at first.

"Think about the money it takes to uniform everyone," Nakagawa said. "The women took mattress ticking and made uniforms. Moms made sliding pads."

Eventually teams started asking for quarter donations at the gate to help with expenses and fans, with little other outlet to keep them distracted from how their lives had turned, were happy to come and chip in to catch a game.

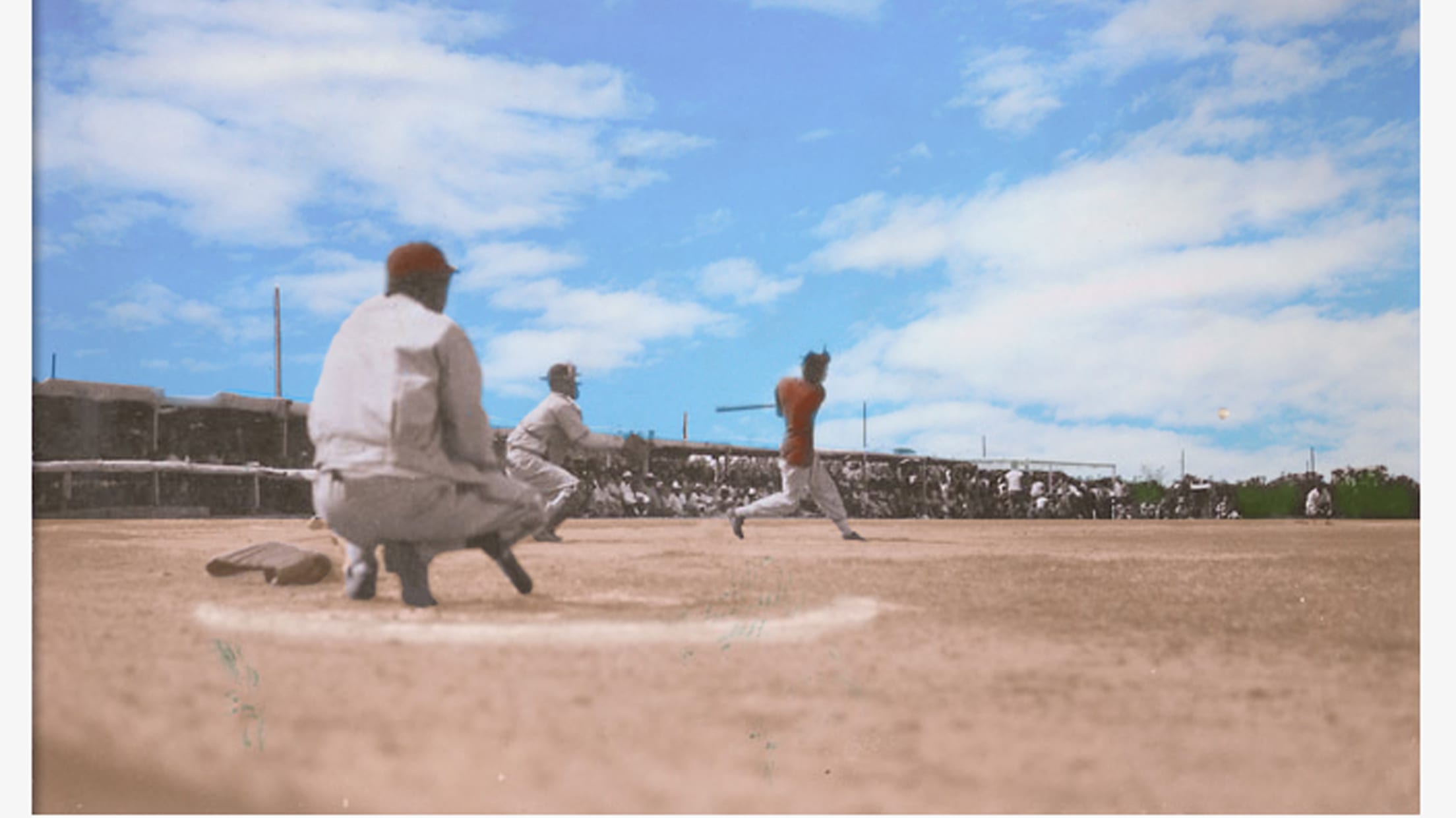

"It was vital for the self-esteem to have a positive kind of mental outlook," Nakagawa told me. "The fans were like 8,000 or 9,000 deep all the way around from left field to center field to right field to home. Where would you rather be? In a 20-by-100 barrack that was roped off into quadrants with a blanket draped over for your privacy? In 120-degree heat? ... I would rather be out there cheering on my favorite player or my favorite community team."

So, of course, when the '45 matchup between the Butte High Eagles and state champion Badgers happened, fans came out in droves.

Zenimura, who coached the Eagles -- his two sons, Kenzo and Kenshi, played -- had heard about the success of the Tucson High team and wanted to take them on. Not every coach accepted Zenimura's challenges (he would use the Arizona Republic to promote his team or write letters directly to schools), but Tucson head coach Hank Slagle had a unique background.

"Slagle was from the Phoenix area," Staples told me. "He had played for a high school called Phoenix Union where he was the shortstop and the second baseman was a guy named Bill Kajikawa, who was Japanese-American. And the two of them were close teammates. ... This early relationship in the mid-30s kind of laid the foundation for somebody like Hank Slagle to be open-minded and go into the camps and take advantage of this opportunity."

Even though Slagle seemed to know who and where they'd be playing, the kids weren't so sure what was going on in these camps. They were surprised to find out these were American high school kids, just like them.

"They thought they were going to be playing young kids from Japan," Staples said. "They didn't really understand the social and political implications of what they were entering. So, during pregame warmups, they start listening to these players and realize they're speaking English. And all of the Japanese-Americans are from California. So, they had to quickly adjust and get their head around what they were experiencing here."

"The kids didn't know they had dragged people into these camps that were U.S. citizens," Bailey recalled. "They had no idea. That was shocking."

And the group also quickly learned how good the Butte team was.

The Butte teenagers had spent the last couple years playing against barnstorming semi-pro and rival camp teams with much older adults as the opposition. They'd faced stronger, faster men. They were also undefeated so far that season. The high-schoolers were more than adequately prepared for the game, and later, many would go on to play college and even pro ball.

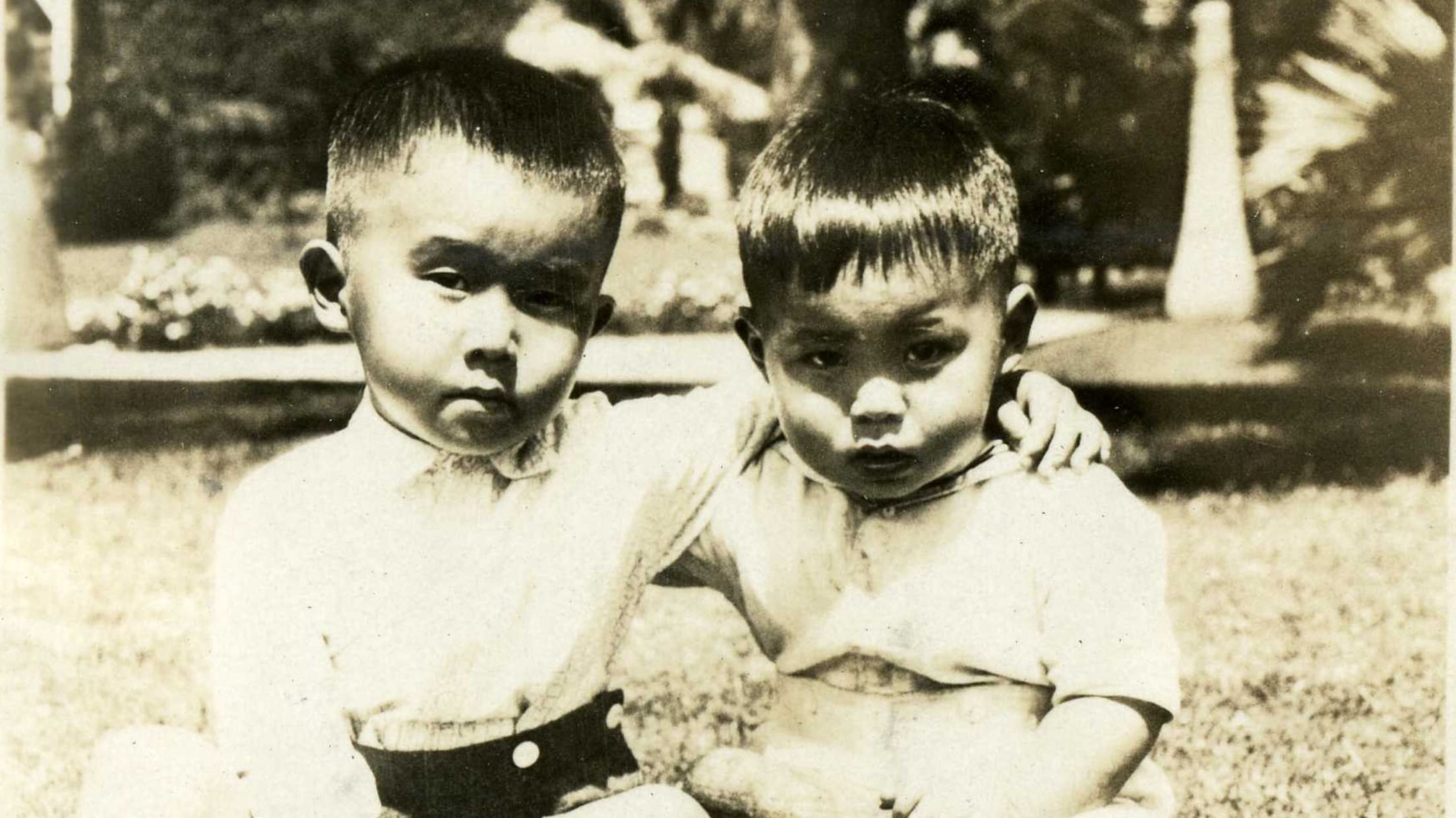

"Several of them went on to play college ball at Fresno State and Cal Berkeley," Staples said. "But two of them -- Kenzo and Kenshi Zenimura -- went on to become the first Americans to play for the Hiroshima Carp."

The contest ended up being a thrilling back-and-forth affair.

The Eagles played an errorless game and showcased smart, timely baserunning. They rallied to come back in the second, sixth and eighth innings and the two teams headed into the bottom of the 10th frame, tied, 10-10. Butte had the bases loaded with two outs. The crowd was delirious, the dugouts were tense. Here's Nakagawa on what happened next:

"There was probably 7 [or] 8,000 internees at that game," Nakagawa told me. "Kenichi's son [Kenshi] comes up, takes three straight balls, two straight strikes, and then, on the sixth pitch, rips it past third base. The local paper, the Tucson paper, said it was a bloop single -- which, of course, it wasn't."

The ball blew past Tucson third baseman Lee Carey (who would go on to become one of the most prized Cleveland Draft picks in franchise history), and Shoshan Shimaski came around to score the winning run.

I look at it as kind of David versus Goliath.

Zenimura Sr. called it "one of the most thrilling chapters in the history of Butte (Gila River) baseball."

"Pandemonium unfolded," Staples said.

Tucson suffered its first loss in three years, but as Joan Bailey told me, it was one Lowell and the rest of the team could accept. Especially after realizing the ugly situation these kids -- who could've been their own classmates and friends -- were forced into.

"I think they never got over the Japanese fans coming off the stands like they did," Bailey recalled. "Hugging everybody, cheering everybody. It was just really good."

After the game, the two teams had some nice exchanges. They shared watermelon together -- which Gila River families had grown on farms -- and the two sides participated in some sumo wrestling contests.

"They dressed me up in all this sumo wrestling garb," Lowell remembered years later. "I went out there and this kid who had played ball with us, he was grinning and laughing, and he picked me up and stuck me."

"I realized that these kids were Americans, just like myself," outfielder Bernie Weinstein later said. "The more I thought about it, the more I thought what a big mistake it was putting these people in a relocation camp."

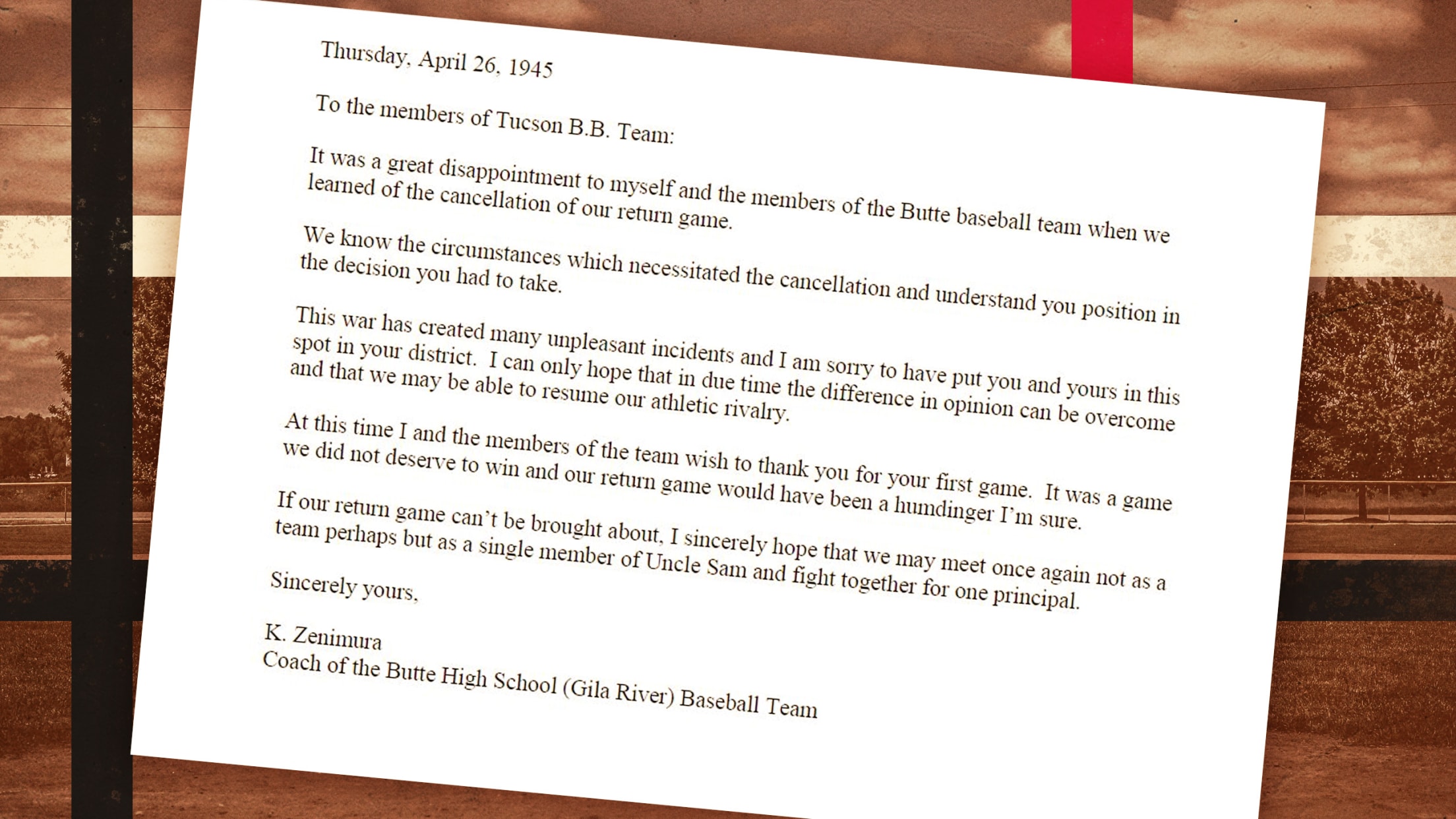

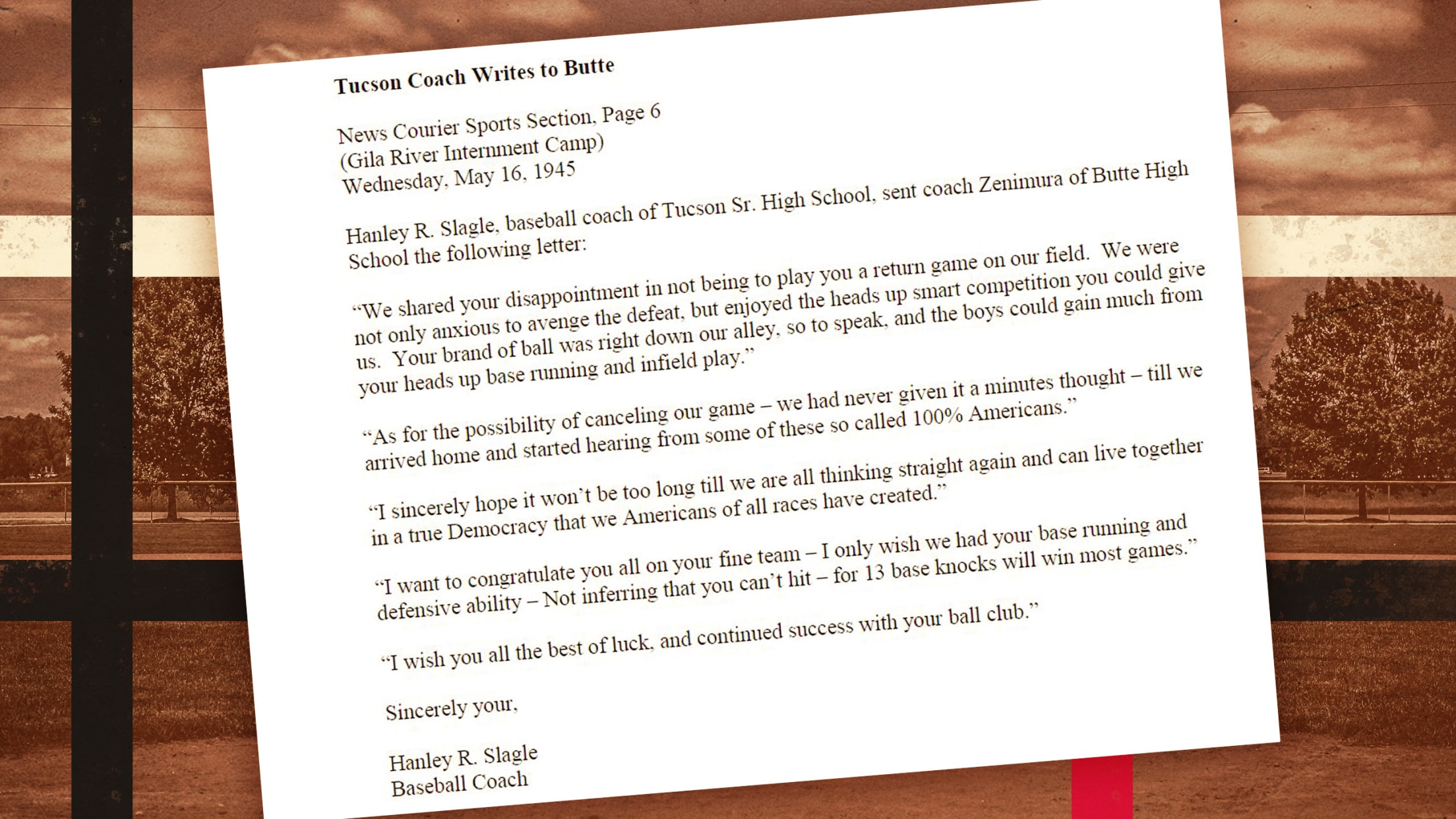

Unfortunately, a return matchup between the two teams a few weeks later in Tucson was cancelled. Tucson was a bit different from other parts of the state, and as Nakagawa put it, that county "didn't feel that [the Eagles] were 100 percent Americans. They were enemy aliens."

Zenimura and Slagle exchanged heartfelt letters after the second game was cancelled, complimenting each other's teams and hoping for a better future for America.

But surviving members of the teams would meet again: 61 years later in October 2006. The Tucson Hall of Fame, a museum in the city that had prevented them from playing a second game so many decades before, inducted the two teams as the Model of American Sportsmanship. They all spent time together at a luncheon organized by Nisei Baseball Research Project.

"They were like Little Leaguers, you know?" Nakagawa, who helped set up the event, recalled. "Talking about the story and the games and the moments. And for both teams to close the circle with the same community that banned them, and now was inducting the teams as the Model of American Sportsmanship, that was pretty special."

And the home plate, the one that Zenimura created with his own bare hands for his dream field, now resides in the National Baseball Hall of Fame forever. It commemorates the enduring, fighting spirit of Japanese-Americans in the face of unimaginable hardship. Hope in the form of baseball.