PITTSBURGH -- Steve Nicosia remembers the conversation he had with Dave Parker in the summer of 1979 well. The Pirates were approaching the All-Star break, and while they were in the playoff hunt, they still had a lot of ground to make up in the National League East.

That didn’t matter for Parker, who made a bold prediction to the team’s rookie catcher.

“He said, ‘Kid, we’re going to win, and in your first season, you’re going to the World Series,’” recalled Nicosia. “Looking back on it, I thought how ironic it was that he said something like that. It came true. It was amazing.”

“I just believed in my fellow players,” said Parker at PNC Park Saturday. “Even when we got down, 3-1, [in the World Series], we felt we were in the right position.”

Of course, Parker was right. That Pirates team would go on to win the division and eventually beat the Orioles in seven games in the Fall Classic. Parker was a major reason why.

While Willie Stargell was “Pops” for that group, Parker was the team’s older brother, as Greg Brown put it during the on-field ceremony honoring the 1979 team Saturday before the Pirates’ game against the Braves.

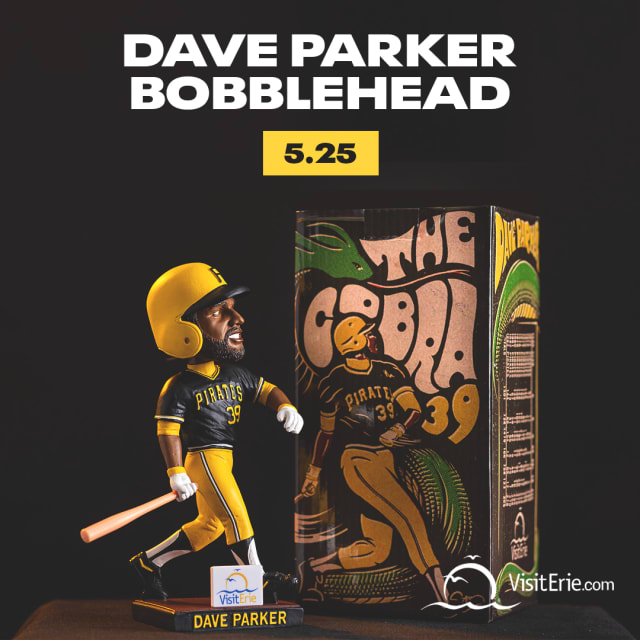

Thirteen players and the families of three more were recognized in a celebration of the 45th anniversary of that World Series team, but a little extra love was given to “The Cobra,” with fans in attendance getting a Parker bobblehead and giving him a standing ovation.

“It’s a great honor,” Parker said. “Something I’ll cherish for the rest of my life.”

Parker spent 11 of his 19 Major League seasons with the Pirates, winning an MVP award in 1978, batting titles in ‘77 and ‘78, and earning four of his seven All-Star nods in Pittsburgh. This is the second time the Pirates have recognized him in recent years; he was inducted into the inaugural class of the team’s Hall of Fame in 2022, though he has not been voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

“It’s about time. All I can say,” Nicosia said. “For a guy like that not to be in the Hall of Fame, it’s a shame and it’s an embarrassment to baseball.”

Parker’s exclusion from the Hall of Fame came up often when talking to his old teammates. While his involvement in the Pittsburgh drug trials of 1985 most likely hurt his cause, he never got particularly close to being voted in despite having impressive counting stats, including 2,712 hits, 339 home runs and 1,493 RBIs. They come up short of some traditional benchmarks customary of Hall of Fame players from his era, like 3,000 hits and 500 homers, but are extremely impressive nonetheless.

Those stats don’t take into account how complete of a ballplayer he was, winning three Gold Gloves and stealing over 150 bases. He was a true five-tool player who was firmly one of the best players in the game for a period of time.

“The things he could do reminded me of what Willie Mays could do,” said Tim Foli. “And he could throw harder than Mays.”

Foli also appreciated how much Parker contributed to that immortal Fam-A-Lee culture, especially with how Parker would joke with his teammates. Foli was the team’s No. 2 hitter and batted in front of Parker, but he wasn’t quite fast enough for the No. 3 hitter’s liking.

“If you could run a little bit, I would have 150 RBIs,” Foli remembered Parker once joked with him. “Can’t you just get a little bit faster?”

Mike Easler remembered before one World Series game against the Orioles in Baltimore, he walked into the clubhouse and there were tables of seafood there, courtesy of Parker.

“It had to have been two, three thousand dollars of crab,” Easler said.

And on top of that, Parker showed the type of teammate he was by his play on the field, even if he was not feeling 100%. In his prime, he was ferocious and rarely was taken out of the lineup.

“Unless he couldn’t walk or lift his arm, Dave wanted to play,” Easler said. “Dave was a baseball player.”

Parker has had a public battle with Parkinson’s since 2012, and his Dave Parker39 Foundation helps raise awareness for the disease. He has still returned to be recognized with his teammates several times in that stretch, remembering him as the elite player he was.

“Back in the '70s, he was a hell of a player,” said John Candelaria. “He hit a ground ball to second base and you had to throw hard. He was running full speed. He wasn’t jogging. He was playing his heart out every day.”