This excerpt of "The Milwaukee Brewers at 50," by Adam McCalvy, is presented with permission from Triumph Books. For more information or to order a copy, please visit triumphbooks.com/brewersat50.

When the call came at 10:15 p.m. on March 31, 1970, Milwaukee County Stadium sat dark and empty down in the Menomonee Valley, a cold reminder of Major League Baseball’s bitter departure five years earlier.

There were no uniforms. No baseballs, bats, or helmets.

No peanuts or Cracker Jack or cold beer.

No ushers. No vendors. No broadcasters.

No whispers of the stories that would be told there in the decades that followed. Of Robin Yount and Paul Molitor and Rollie Fingers. The return of Henry Aaron. Bambi’s Bombers and Harvey’s Wallbangers and Team Streak. Geoff Jenkins and Jeff Cirillo and the rise of Miller Park. Of Prince Fielder and Ryan Braun. Christian Yelich and a hometown kid named Craig Counsell.

When Bud Selig picked up the telephone at his Fox Point home that night, he heard three words from Milwaukee Sentinel sports editor Lloyd Larson that changed the course of the next 50 years and counting:

“You got it.”

With that, Larson slammed down the telephone and chased deadline. The Milwaukee Brewers were born.

A telegram the next day confirmed it. Selig had one week to put everything in place for a Major League game.

“It had been five and a half years of disappointment after disappointment,” Selig said. “I remember that night I took a walk, thinking, ‘Who would have dreamed after all these years of wanting to own a Major League Baseball team, and now we do?’ Wow.”

+++

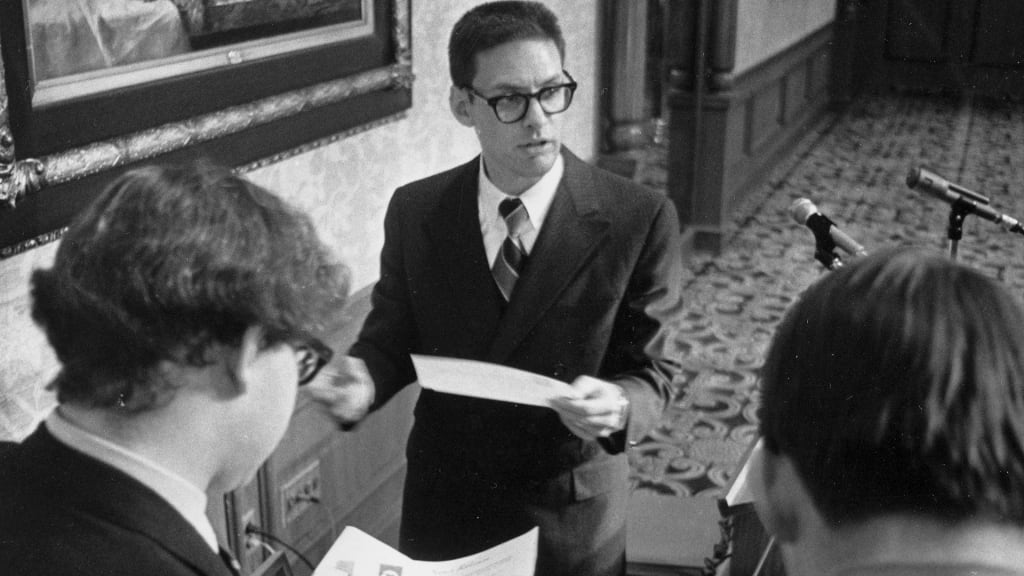

On April 1, 1970, the morning after that late-night call from the newspaper editor, it was official. Federal bankruptcy judge Sidney Volinn delivered a ruling that meant the Seattle Pilots could be sold to a group in Milwaukee led by Selig.

We’re Big League Again! Court OKs Sale of Pilots, read the headline in the Milwaukee Journal.

Opening Day was a week away.

For a few days, while Milwaukee County employees cleared the lower grandstand of several inches of snow, Selig was the team’s only employee. He was moving so fast, solving so many problems on the fly, that the details are sparse these decades later. There was a stadium manager, William R. Anderson, employed by the county. He ran a small grounds crew that had already been prepping the field for the potential of baseball. Members of the Pilots front office were told that if they wanted to move from Seattle to Milwaukee, their jobs would be waiting. Selig also brought back two or three former members of the Braves front office, who’d helped out when County Stadium hosted the White Sox. The most expensive season-ticket packages went for $375. The most expensive single-game tickets were $5.

On Friday, April 3, Selig showed up to work and a temporary employee was waiting. Her name was Betty Grant, and there would be nothing temporary about her assignment; Grant ran the Brewers’ switchboard for 33 years, spanning 13 managers, eight general managers, three club presidents, and two stadiums before hanging up the telephone for the last time in 2003 at Miller Park.

(Fun fact: [Bob] Uecker sometimes worked the switchboard in those early years. He remembers Selig being furious one day when Uecker inadvertently disconnected a conference call with the other owners.)

That first day, Grant sat on the floor.

“Everything happened so fast,” Grant said the day she retired. “[Selig] called me in and said, ‘Get to work.’ So I started selling tickets, even though I didn’t know the first thing about selling tickets.”

“None of us did, I can assure you,” Selig said.

On Saturday, April 4, the team’s general manager, Marvin Milkes, asked for fans’ patience with operational problems, since “we’ve got to do four months’ work in four days.” On April 5 -- two days before the opener -- the playing field was certified by representatives of the American League, and concession stands were stocked with beer. That night, the Pilots-turned-Brewers landed at General Mitchell Field in Milwaukee with as many as 8,000 fans waiting in the terminal after 10:00 p.m.

“I thought we would get a welcome,” said rookie outfielder Danny Walton, “but never one like this.” Milkes called the reception “something I didn’t think existed anymore. I just hope we’ll be worthy of them.”

By a stroke of fortune, the Pilots’ traveling secretary was Tommy Ferguson, who’d held the same job for the Milwaukee Braves before they departed for Atlanta. That meant Selig knew Ferguson. He was happy to know somebody. Ferguson got the first flight to Milwaukee, but the rest of the Pilots, including their 36-year-old manager, Dave Bristol, were still out west. While Bristol and his players absorbed the news in Tempe, Ariz., the equipment truck was in Salt Lake City. The driver was awaiting word of whether to drive northwest to Seattle or northeast to Milwaukee.

“[Ferguson] said, ‘What do I do about uniforms? They’ve got S on them,’” Selig recalled. “I said, ‘Well, you rip off the S and put on an M. That’s all we have time for.’ And that’s exactly what happened.”

Selig originally had more nostalgic plans for the new team’s logo and color scheme. He wanted navy blue and red, the colors not only of his beloved Braves but of their predecessors, the Minor League Milwaukee Brewers. But there was no time for that.

So, if you’ve ever wondered why the Brewers’ color scheme is blue and yellow, you can thank the Seattle Pilots.

“At that point, I just wanted to get us on the field,” said Selig.

On April 7, after years of trying and countless disappointments, the Brewers did get on the field. Under bright sunshine, right-hander Lew Krausse threw the team’s very first pitch to Sandy Alomar of the California Angels. Right fielder Steve Hovley singled with one out in the second inning for the Brewers’ first hit. He reached safely in all four of his plate appearances, including three hits. In terms of highlights for the home team on that historic day, that was about the extent of it.

Tommy Harper had the Brewers’ only other hit in a 12-0 loss to Angels righty Andy Messersmith, who tried to spoil the day by pitching a shutout on four hits in front of 36,107 fans, the third-largest Opening Day crowd in baseball that year.

Think about that path to that first Opening Day. It’s impossible to fathom a similarly frenetic week in today’s game. When Selig oversaw subsequent moves as MLB Commissioner, the details were worked out months and years in advance. When the Brewers played their first game, they didn’t even have a lease to play at County Stadium. They played the first two games on a handshake agreement.

“He’s pulled this stuff off his whole life,” said Yount. “There have been times when we sit down across a table ... and we go, ‘Can you believe what has happened to us in this silly game?’ Who would have thought 50 years ago that the two of us would be in the Hall of Fame?

“We look at each other like, ‘Really?’”

How many people did Selig and Yount influence along the way? Not to mention Molitor and Fingers, Jim Gantner and Cecil Cooper and Gorman Thomas. Jenkins and Cirillo. Fielder and Braun. Yelich and Counsell.

But on that night in 1970 when the phone rang with news from Seattle, there was just Selig.

He was 35 years old.

“I was young. Maybe too young to know that the odds were really stacked against us,” Selig said. “It was a simpler time, there’s no question about that. But even in that simpler time, it was an amazing story.”