Swanee's hometown dream came true in KC

KANSAS CITY -- In 2006, Mike Swanson came home.

After his ninth season as the senior director of public relations for the D-backs, Swanson was looking for a change. Shortly after he turned down a job with the Cubs, the Royals called. They had an opening for the role of vice president of communications and broadcasting. The job was Swanson’s if he wanted it.

It was a chance to bring his family to Kansas City, where Swanson had grown up and started his career in sports. He couldn’t pass it up.

“It was so cool to be back with my hometown team, back with a team that George Brett is still involved in, with a team that literally played in a stadium three miles from my house growing up,” Swanson said. “It doesn’t get any better. And then we win in 2015.

“Now what? Now you retire.”

Fifteen years after Swanson joined the Royals' organization, he’s saying goodbye. It’s his 43rd season in Major League Baseball, a journey that has also seen him go through San Diego, Colorado and Arizona; serve as the public relations liaisons for the MLB All-Star team that played in Japan in 2000 and the Dominican Republic teams in the '13 and ’17 World Baseball Classic; and earn the prestigious Robert O. Fishel Award for Public Relations Excellence in '02.

• 'Swanee' honored during ASG broadcast

Tuesday marks the beginning of the Royals' final homestand of the 2021 season -- and Swanson’s final as their public relations director. At the end of the year, the 67-year-old is retiring, marking the end of an era in baseball and the Royals' organization.

“That is one of the most crucial positions in the organization, because you’re dealing with so many different personalities,” president of baseball operations Dayton Moore said. “It takes somebody like Swanee, who can create a bridge between the players, front office and coaches with the media. That’s what Swanee has been able to do so well for 43 years.”

*****

The first thing to know about Mike Swanson is that no one calls him that. It’s Swanee, and it has been for as long as he can remember.

“I walked into our first meeting when he was hired, gave him a handshake and said, ‘Hello Mr. Swanson,’ because he’s my boss,” Royals broadcaster Ryan Lefebvre said. “And he pulled me in, gave me a hug and said, ‘It’s Swanee. Don’t ever forget that.’”

The second thing to know is that he’s revered around baseball. Swanson didn’t think that by announcing his retirement in June, he would receive as much attention as he has in opposing ballparks. He wanted to be able to say his goodbyes, but he didn’t realize how many people wanted to do the same.

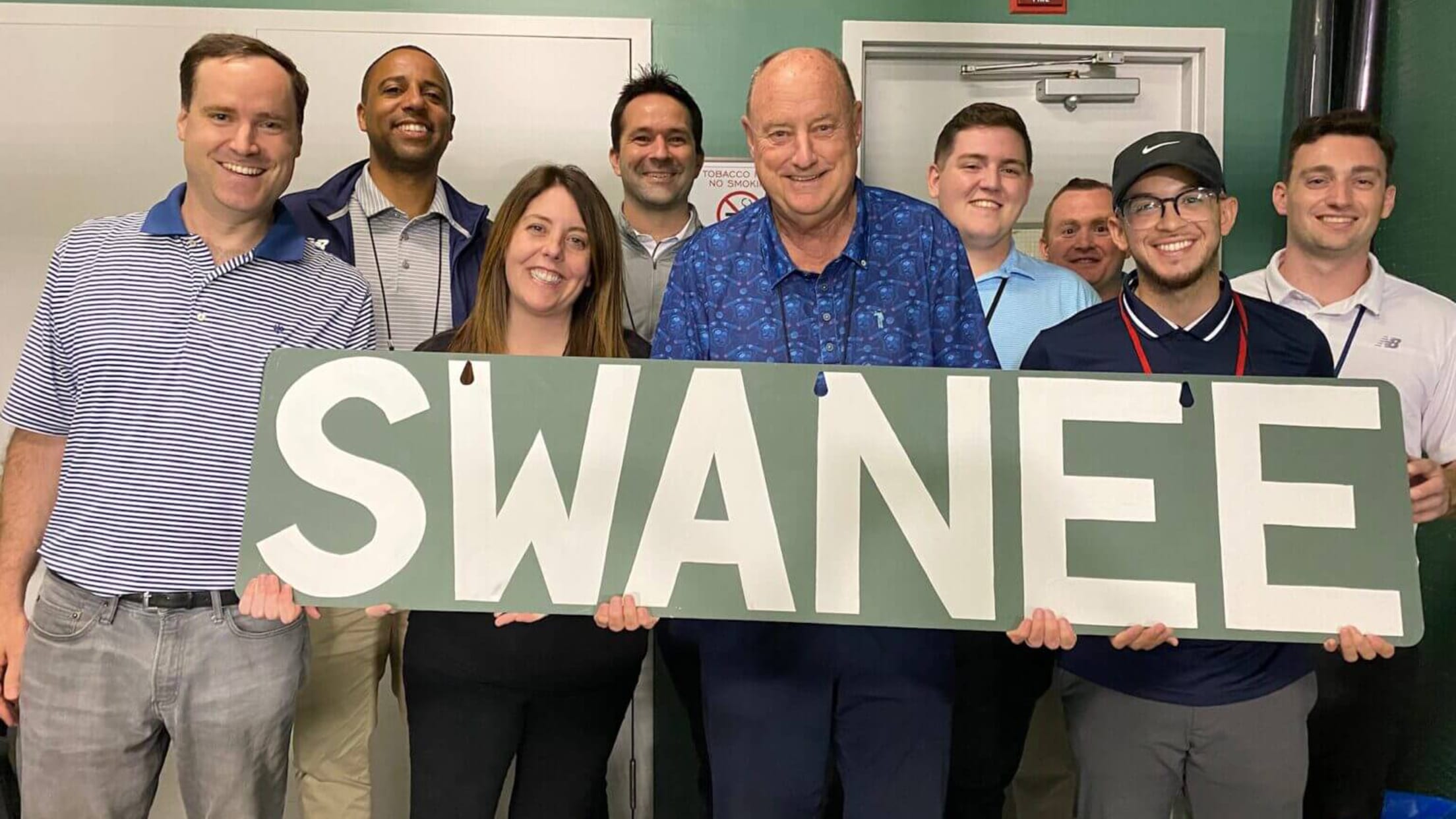

He has received scoreboard tributes, cake celebrations and plenty of gifts on the road over the past few months. He got a piece of the Green Monster at Fenway Park with white letters spelling out “Swanee.” The Twins gave him a personalized putter. The Astros and Mariners sent him home with golf balls and golf clothes.

He even threw out the first pitch at Wrigley Field in August.

“The role I’ve had for 43 years has been that of a behind-the-scenes person that gets the not-behind-the-scenes people doing stuff,” Swanson said. “You do it, and you don’t think you’ve done anything special, anything out of the ordinary.”

But Swanson is anything but ordinary.

*****

“Why is Swanee so good at it?” posed Cubs broadcaster Boog Sciambi, who has gotten to know Swanson while calling postseason games for ESPN. “He’s beloved by the players and beloved by the media. He’s able to execute the job exactly how it should be done.”

Swanson knows how to deal with ownership, management, players and media. In a time when the team-media relationship around MLB sees general distrust, and at times, tension, Swanson advocates for it -- and he makes sure his players know.

“I learned so much from the first rookie camp we had after I got drafted, and it’s because of Swanee,” said Mike Moustakas, the No. 2 overall pick in the 2007 MLB Draft and a core piece of the Royals' championship team. “The one thing he always told me is go up there and answer the questions honestly. He would make sure we were accountable, but wouldn’t let anything bad happen to you.

“One of the most trustworthy people I’ve ever been around. I was so blessed to be part of the Royals' organization, and he was a huge part of why we all felt so comfortable.”

The trust people have in Swanson allows him to connect with all parties, and he can handle any hectic thing thrown his way. That comes with 43 years in baseball -- and some advice from Tony Gwynn.

One night over a few drinks, Swanson, who was working for the Padres at the time, asked Gwynn how he’s able to be one of the best hitters the game has seen.

“He goes, ‘Swanee, it’s hard to explain. But I just happen to be able to put whatever’s going on in slow motion. If it’s 93, it’s just not coming in at 93 to me; I’m able to react,’” Swanson said. “I never tried to hit a 93 mph fastball, but the words stuck with me.

“I’ve had more than my share with spur-of-the-moment things, from winning the World Series title to losing it. MVP moments. Fights on the field. Whatever it is, I’ve always been able to take 10 seconds and go, ‘OK, what’s the first thing I have to do?’ And just get it in some sense of order in my mind or in my notepad. Then act.”

Sometimes it’s a job that requires veering off-course. In Spring 2002, D-backs outfielder Luis Gonzalez spit out a piece of bubblegum that would become an object of national intrigue for nearly two weeks. A fan had picked up the gum and put it up for sale on his website. A disc jockey in Arizona came across the auction. That’s when the gum became a national sensation.

The gum’s legitimacy was called into question. It was all anyone could talk about. Meanwhile, the D-backs weren’t playing well. Swanson knew he needed to steer the attention back to baseball.

So Swanson organized a media scrum in the Coors Field dugout on April 11, 2002, and had Gonzalez chew a piece of gum, seal it in a canister and send it off.

“I think Swanee thought the thing was ridiculous,” Gonzalez said. “I remember him saying, ‘We’re not playing good right now. We have to get past this bubblegum thing.’ And a few other choice words.”

Gonzalez was willing to do it because he trusted Swanson. The five-time All-Star finished third in NL MVP voting in 2001, and he delivered the walk-off hit in Game 7 of the World Series. He often was the go-to voice on that team, so he relied on Swanson to tell him what media obligations to fulfill.

“First of all, he’s just a great friend,” Gonzalez said. “Someone who you always felt like he had your back. He wasn’t going to put you in an uncomfortable situation. Sometimes you have your blinders on, and he’s checking your rearview mirrors. He’s looking around to see what’s going to be the best path for you to take. He was always that guy for me.”

Swanson makes sure the media could do its job, too. That meant asking players to be accountable and answer for a bad game. Or taking a rant from a manager -- he’s worked with 17 -- before he went into the press conference room after the game.

“Everybody says, 'Well, that’s his job,'” longtime Kansas City sports reporter Frank Boal said. “And sure, it is. But it’s the way you do your job that’s the important thing. And no one does it better than Swanee.”

*****

The balance Swanson struck with the front office, clubhouse and media has been shaped from wisdom gathered over 43 years. But it started long before that, when Swanson was a young boy from Raytown, Mo., and the son of the late Betty Swanson, who worked for both the Kansas City Athletics and Chiefs over a 36-year span.

In 1969, 15-year-old Swanson was asked if he wanted to work Chiefs training camp in the summer in Liberty, Mo. He said yes without hesitation and did a little bit of everything: water boy, ball boy, cleaning gear, packing equipment.

As he did all that, Swanson observed the players. And he learned from them.

“The players were my second through 50th fathers,” Swanson said. “I couldn’t be a jerk or anything like that, because they wouldn’t let me. My dad was my dad, and he was pretty good at discipline. And then I got Willie Lanier and Curley Culp and Len Dawson. … I could go through the whole list of players. They’re like, ‘Don’t be an a-hole.’ So you learn how not to be. Very quickly.”

Boal added: “I think that’s where Swanee started to get his understanding of what the relationship should be between players and the media. He got a pretty good dose of that in the Chiefs' locker room.”

He’s beloved by the players and beloved by the media. He’s able to execute the job exactly how it should be done.

Boog Sciambi

Around that time, legendary groundskeeper George Toma asked Swanson what he wanted to do with his life. Swanson said he wanted to stay in sports but maybe not with the Chiefs, where he was always “Betty Swanson’s kid.” Toma checked with Bob Wirz, head of Royals PR, who asked Swanson if he knew anything about statistics.

“I say, ‘Yeah, I dabble a little bit,’” Swanson said. “So I become an intern with them in 1973, and I’m not even 19 years old. I end up parlaying that into six seasons. I meet some people during that.”

Swanson met iconic broadcaster Keith Jackson, who hired Swanson as his statistician for college football games, as well as the Monday Night Football crew of Frank Gifford, Don Meredith and Howard Cosell. In 1982, CBS hired Swanson, guaranteeing at least 60 games with a variety of broadcasters.

Swanson lists some jaw-dropping names, including NFL Hall of Famers Pat Summerall and John Madden, before saying, “At this point, you’re probably wondering, ‘How did you end up in baseball?’”

Swanson was on assignment for CBS at the 1984 All-Star Game, where he met and impressed broadcaster Jerry Coleman. A few weeks later, Swanson was hired to work in Padres PR. That’s where his baseball journey began. He was on two startup teams in Colorado, joining the Rockies in '92 before their inaugural year, and Arizona in '97.

Swanson joined Kansas City prior to the 2007 season and never looked back.

“I was so happy when he came back,” Boal said. “Just the way he helped us. And then he went from handling one of the worst periods of this franchise’s history to handling the other side of the coin. Champions.”

*****

It took Swanson time to decide whether he should retire, and even more time to tell Moore and Royals owner John Sherman. But there are many reasons why Swanson came to the conclusion that this was it.

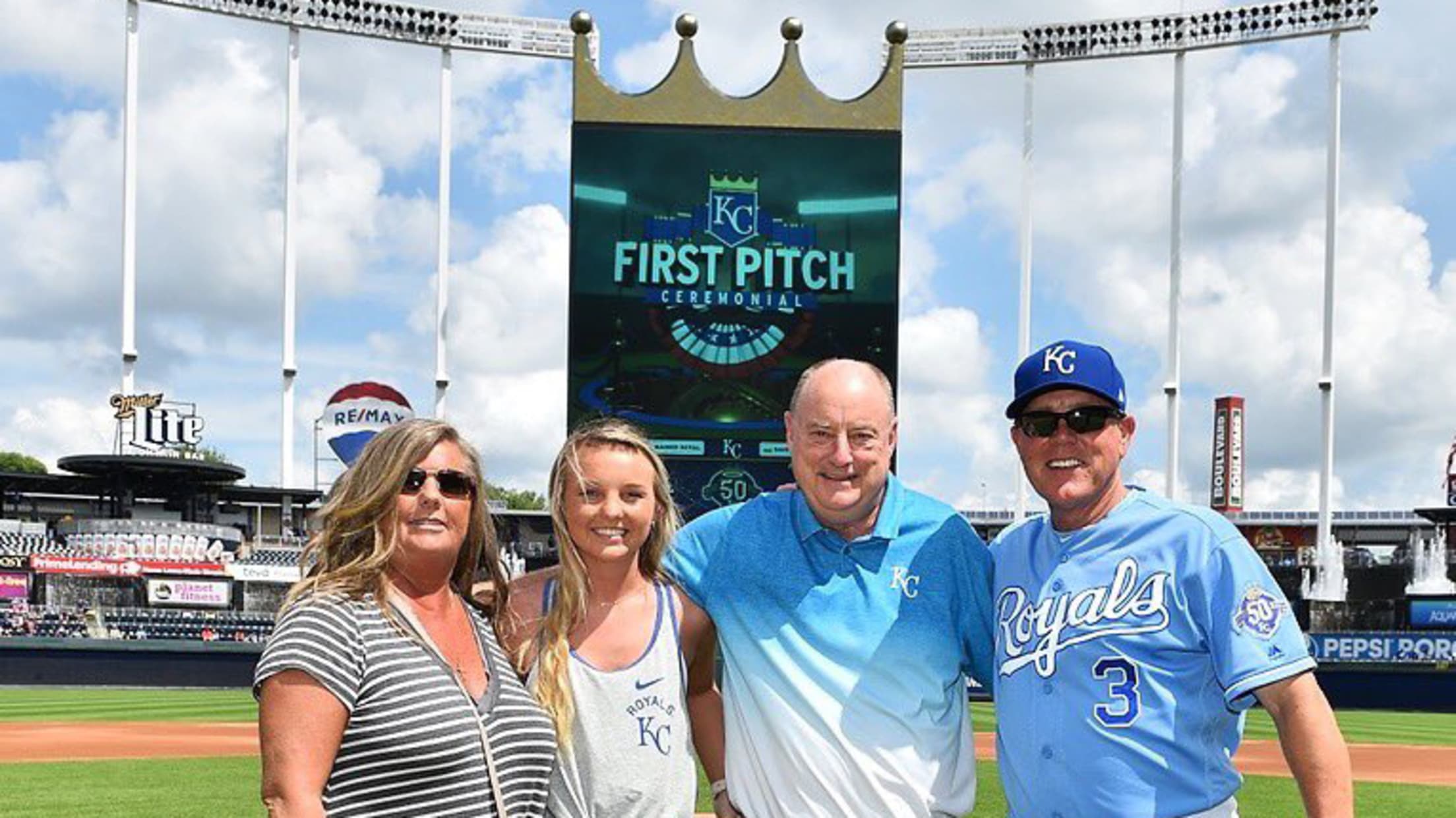

Baseball involves a grueling schedule of 12-hour days over an eight-month period. Swanson is healthy and wants to see what life is like away from the stadium. His daughter, Rachel, recently graduated from the University of Kansas and is beginning her own career in sports.

Swanson wants to be there to watch her thrive.

“I just feel like I’ve given all I can give,” Swanson said. “Not that I don’t have more to give, but I can’t do it on the consistently hourly basis that I’ve done it.”

He pauses, then continues: “I’m conflicted, don’t get me wrong. I can’t sit here and say I know I made the right decision. I guess I’ll find out. But for right now, it’s the right decision for me.”

Swanson is so good at his job and so beloved around the Royals' organization that it’s hard to believe he won’t be around next year. Royals officials have tried to convince him to stay. Many around the league aren’t sure what it will be like without him.

“I’ve never worked baseball without Swanee there,” White Sox media director Bob Beghtol said. “He’s one of those guys that everyone knows. They say baseball waits for no one, but this is a tough one. He’s still in the business of having fun and building relationships and enjoying it.”

Swanson is open to consulting or advising for the Royals. He’s also not opposed to more stats jobs. But for the most part, he’s ready to see “what life is like on the back nine.”

“It’s cool to feel like you’ve had just a tick of an impact,” Swanson said. “If you don’t try to make the game better than you found it, what are you doing? We’re caretakers of a sport that’s been around long before we got here and will be around long after we leave.

“When I’m done on [Sunday] watching games, they’ll play games next year. I’ll be cooking steaks on the grill in the backyard. Or I might be on a golf course.”