Between Miggy and his mom: 'I hit better than you'

When Miguel Cabrera reached 3,000 hits a couple of weeks ago, the list of exclusive clubs he joined seemed never-ending. Thirty-third player and the sixth from Latin America to reach that number. The seventh with 3,000 hits and 500 home runs in the Major Leagues. The only one with 3,000 hits, 500 home runs and a Triple Crown to his name. Just one of three players with 3,000 hits, 500 dingers and a .300 average or better, along with Willie Mays and Hank Aaron. And the list goes on.

But beyond the numbers and records, the hit to right field off fellow Venezuelan Antonio Senzatela of the Rockies meant something more to Cabrera. After 20 years in the Major Leagues, he finally put an end to the oldest debate of his professional career, a topic of conversation that served as a source of motivation and still generates laughter from him and his loved ones: Being recognized as the best hitter in his family.

Although it does not appear in any official record books, until recently that distinction belonged to Cabrera’s mother, Gregoria Torres. Or at least that’s what she’s been telling him since he was a teenager.

“She’s always told me that she hits more than me,” Cabrera said recently during a Zoom press conference. José Miguel Cabrera Sr. confirmed this from his home in Maracay, where his son and namesake were born and raised. “One time she told him, ‘If you want, I’ll hit for you,’” recalled Cabrera Sr.

Did she say that to Miguel when he was still a youngster?

“No, as a grown-up in the big leagues,” said Cabrera Sr. “I think it came up last year. Totally joking.”

But no more. The matriarch, who made a name for herself on the diamond as part of Venezuela’s national women’s softball team and various state teams from Carabobo, Aragua and Lara, has ceded the throne. She told Miguel so during the days they spent together in Detroit, waiting for him to get his long-anticipated 3,000th hit.

“We talked about that and how it’s no longer the case. Now, he’s the better hitter because you have to have heart to get to 3,000 hits. That’s not easy,” said the mother of the four-time batting champ and two-time American League Most Valuable Player. “I don’t say that to him anymore. No one can tell him that. I can’t say it anymore.

“Before, yes, I would tell him all the time that I could hit more than him, that I was better than him, things like that. It was primarily to motivate him, and he likes that; it makes him happy. When you talk to him like that, he smiles, and it brings him joy. He likes it.”

Cabrera always viewed that competition with his mother as just that, a source of motivation. “We have a good thing going with that,” said the future Hall of Famer. “I like when she tells me things like that, that she always finds a way to motivate me. She’s one of the first people to criticize me when I’m not hitting. She’s always been tough on me when it comes to playing baseball.”

The banter is mutual. A year ago, in a Mother’s Day message he published on Instagram, Cabrera didn’t pass up the chance:

A COMBO OF CAL RIPKEN JR. AND MIGUEL

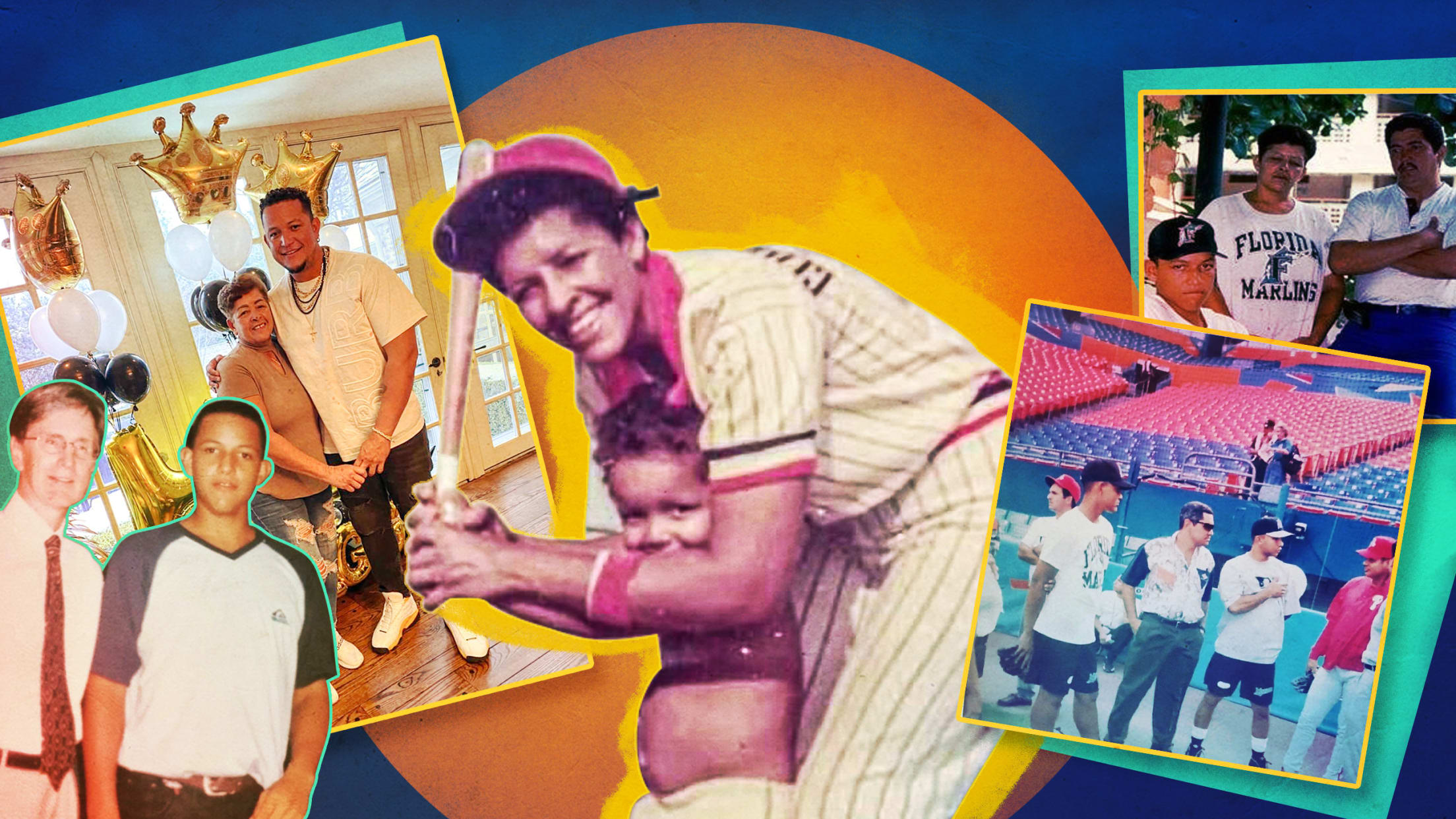

Miguel Cabrera doesn’t have many memories of his mother playing softball, although he traveled with her to various tournaments. “He shared moments with me when he was very young,” said Torres. “I have a photo from when I played with the Carabobo team and we were in Cabimas and he’s there in the middle. He was 3. Someone sent it to me around the time he got 3,000 hits.”

When Cabrera began to show his talent and love for baseball, Gregoria decided it was time to leave the field and focus on raising her children, Miguel and Ruth.

“I said to myself, ‘Either I play or he does,’” Torres recalls. “I did it to devote more time to him. He was already 7 years old and his sister was 3. It became more difficult.”

Torres walked away after 14 years with the Venezuelan national team, which included an appearance at third base and at catcher in the Women’s Softball World Cup hosted by Chinese Taipei in 1982, a year before Miguel was born. “There, I was part of the All-Star team,” she said with pride.

Germán Robles was the Marlins scout who first told his bosses about a prodigious young player named José Miguel Cabrera that they absolutely had to see. They ended up signing him on July 2, 1999, for $1.8 million. Robles also saw Torres, a distant relative whom he had known by the nickname “Goya” from the La Pedrera neighborhood of Maracay.

The Torres family has baseball in its blood. The family home was next to a baseball field where Gregoria’s brother, David -- who has since passed away and was considered Cabrera’s first coach -- ran a baseball training program for kids. David and José, her other brother, played professionally. Her sisters María, Bertha and Juana also played softball.

“It was like watching Cal Ripken Jr. at third, with Miguel’s bat,” said Robles, describing Torres via phone from Valencia, where he is the scouting coordinator for the Washington Nationals in Venezuela. “She was very good. Great hands, a fantastic arm, power. A strong, determined woman. A tremendous athlete.”

“Goya really could hit,” added Cabrera Sr. “First, she hit second and played shortstop, but later she developed strength and hit third or fourth with the national team.”

If you ask Torres what kind of hitter she was, whether she hit for power or average, she responds with a mix of confidence and humor: “Well, both. That’s why I would tell Miguelito that I was a better hitter than he was.”

In other words, “Goya” had the authority to speak about and give opinions regarding baseball. She still does, although she notes that with Miguel she tries not to go too deep into technical things.

“Sometimes, I’ll tell him, 'Hey, they’re pitching you outside, really far outside,'" she said. "But that’s one thing. You can’t tell Miguel, 'Lift up your arms, you are dropping the bat too much.’ You can’t say those things to Miguel. You can’t because you’re telling one of the best hitters in the world how to hit. He’s in a better spot to give advice.”

GROOMING A PROSPECT

With Miguel determined to focus on baseball, the Cabreras’ original plan was for his uncle David to train him before signing with a Major League team. His untimely death changed everything. Gregoria and José Miguel Sr. decided to sign their 14-year-old son up with a team in Cagua, a small city near Maracay, and take control of his training and representation. No academies, no agents. And, with the same condition as always: He had to continue his studies and graduate high school.

“Fortunately, he listened,” said Torres. “And we were of strict character. He would get home and the first thing he had to do was his homework before practicing. If not, he couldn’t go.”

Robles witnessed first-hand everything that Gregoria and José Miguel Sr. did to ensure that Miguel had everything he needed, including the means to travel with the various state and national teams he belonged to.

“It involved a lot of sacrifices,” said Robles. “I remember that Goya sold handcrafts and organized raffles. His dad saved everything he earned fixing cars so that Miguelito wouldn’t want for anything. That has great value, because his parents really were always looking out for Miguel and Ruth.”

Cabrera was coached by his dad in various aspects throughout his childhood and adolescence. But it was also normal for his mom to accompany him on trips with the travel teams he played on.

“In fact, during many of Miguelito’s workouts, when Miguel played with local teams, they were led by his mother, who was with him,” said Robles. “She would hit him ground balls and throw batting practice, along with his dad.”

No one remembers the exact date, but it was before Cabrera signed with the Marlins -- probably during one of those few games when the future slugger did not perform well -- when Torres told him for the first time that she was better than him at the plate.

“That was always in good fun. She would tell him to get him to hit,” noted Cabrera Sr. “It didn’t always happen. But in competition, he always did well.”

But that grew into an ongoing inside joke between them, one that lived on as Cabrera made his way through the Minor Leagues and eventually to the Majors. A bond between a son and his mother. A world that no one else had access to. Is there another person who can tell Cabrera that they’re a better hitter? “No one,” said his father.

THE PERFECT GIFT

Like a devoted mother, Gregoria Torres has always been proud of her son. But she acknowledged that waiting for the milestone hit, and all that it represents, “was even more exciting.” She experienced something similar when her son reached 500 home runs.

Cabrera could tell how happy and excited his mother was during the days they spent together at the slugger’s home in Detroit.

“I don’t think she could be prouder, because I saw it in her face the last few days,” Cabrera said. “I saw how excited she was when the tears came. That’s something that gives me a lot of pride, because all that she taught me, all that she did to help me move forward, got results.”

That’s what made Cabrera’s embrace with his wife Rosangel, his two children and his mother on the field after the historic hit so special. The only one missing was his dad, who was not able to make the trip to Detroit from Venezuela because he was waiting for a new visa. “Family is everything in life,” said Cabrera.

“Proud?” asked Torres. “There are no words for that. I don’t know how to express so much joy, so many emotions, so many things at the same time. It’s too much. I am so, so, so proud of my son.”

She’s so grateful for her life that sometimes, without knowing why, she cries in her room. But they are tears of joy for sure: “I say thank you, thank you to God, because sometimes there are no words.”

With the Tigers on the road this weekend, Cabrera will not be able to spend Mother’s Day with his mother, who stayed in Miami. Was hit No. 3,000 enough for a gift?

“You never get tired of giving your mom gifts. [A mother] is the greatest thing in your life after your kids,” said Cabrera. “I will be grateful to her my entire life. Any token, anything I can get for her, I will always give it to her.”

But Gregoria Torres doesn’t ask anything more, except good health for her son.

“He already gave me a gift,” she said. “He gave it to me in advance.”

Perhaps Miguel Cabrera achieved a lot more than the obvious the day he got to 3,000 hits in the Major Leagues. Yes, first are all the records. Then, securing his place as the best hitter in his family. But he also found, with that milestone hit, the perfect Mother’s Day gift.