A version of this story appeared on MiLB.com in 2021. We present it here, with updates, as MiLB and MLB celebrate Black History Month.

It's easy to forget that less than 20 years separated Jackie Robinson's integration of affiliated baseball in 1946 and Dick Allen's Triple-A debut in 1963. Between the time Robinson set foot in Ebbets Field on April 15, 1947, as the first Black man to play in the Majors in the 20th century and Allen's first game with the Arkansas Travelers, 22 Black or Hispanic players had won Most Valuable Player (10), Rookie of the Year (11) and Cy Young (one) honors.

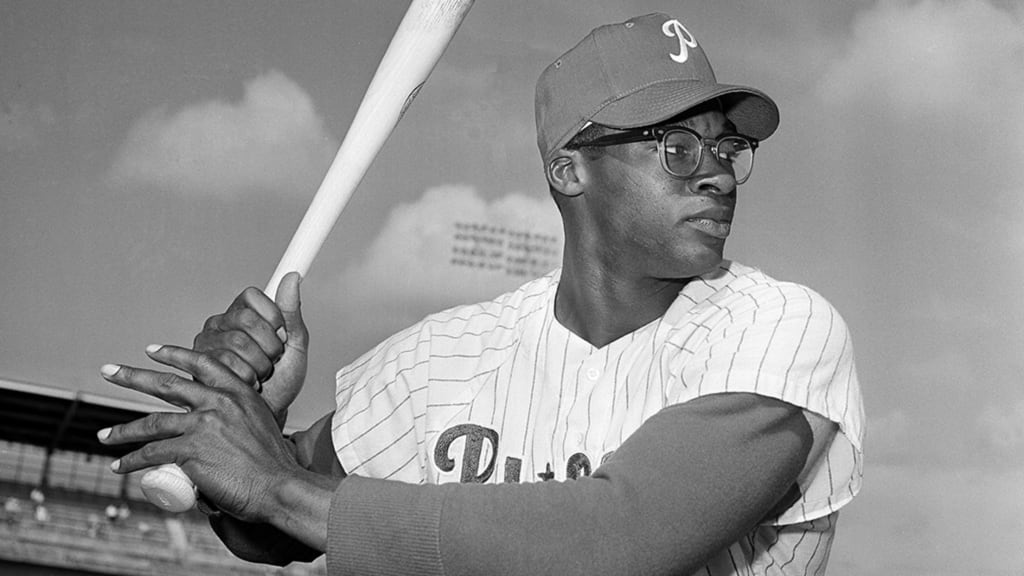

All of that meant little to the still-segregated city of Little Rock, Ark. -- and to the man with a fearsome bat who broke that barrier on the ballfield in 1963. For Allen, success as a Black man in the South came at a cost.

There was immediate pushback to the International League's decision to award an expansion franchise to Little Rock, which hosted a previous iteration of the Travelers in the Southern Association from 1932-61. Arkansas was governed by Orval Faubus, the man who called in the Arkansas National Guard in an attempt to prevent the integration of Little Rock's Central High School in 1957.

In fact, Cleveland Indians president and general manager Gabe Paul threatened to block the move to Little Rock unless there were assurances that Black players from his team's Triple-A Jacksonville squad would be treated the same as their white counterparts during trips to Arkansas. Paul dropped those threats after MLB commissioner Ford Frick vowed that, "our Negro players will receive equal treatment in Little Rock."

In front of that backdrop, Allen was introduced to a new way of life while becoming the first professional Black player to play the game in Arkansas -- an environment where the color of his skin mattered far more than the immense talents he brought to the field. Gov. Faubus threw out the inaugural first pitch in front of a crowd of nearly 7,000 fans, many with hate in their hearts and words. Allen was greeted with signs held aloft that read "Don’t Negro-ize Baseball” and racial slurs with the message: “Go Home.”

Starting in left field, Allen dropped a fly ball on the first play of the game. He wrote in his autobiography, "Crash: The Life and Times of Dick Allen," that he froze. "The ball flew over my head. I missed the ball because I was scared. I don’t mind saying it.”

Allen atoned for his first-inning miscue with a pair of doubles, the second of which set up the Travelers' first win. But his success did little to quell the ingrained racism from the home crowd.

"I didn’t know anything about the racial issue in Arkansas, and didn’t really care," Allen wrote in his book. "Maybe if the Phillies had called me in, man to man, like the Dodgers had done with Jackie Robinson, at least I would have been prepared. Instead, I was on my own."

The slugger wasn't blind to the struggles Black people faced in America, but hailing from Wampum, Pa., shielded him from the level of vitriol he'd experience in Little Rock.

“[Following the first game] I wanted to be alone. I needed to sort it all out," Allen wrote in his autobiography. "I waited until the clubhouse cleared out before walking to the parking lot. When I got to my car, I found a note on the windshield. It said, 'Don’t come back again, [slur].' I felt scared and alone, and, what’s worse, my car was the last one in the parking lot. There might be something more terrifying than being Black and holding a note that [includes that racial slur] in an empty parking lot in Little Rock, Ark., in 1963. But if there is, it hasn’t crossed my path yet."

Through it all, Allen didn't let his anxiety affect his play. Newly wed to first wife Barbara, Allen thought it best to leave his bride home in Pennsylvania to spare her the negative experiences ... and there were many. Because of segregation, Allen lived with a Black family in a separate part of town, was stopped by police on numerous occasions and was only allowed to eat in restaurants if accompanied by a white teammate. The enormity of what he experienced led to thoughts of quitting, but a chat with older brother Hank -- also a pro ballplayer -- kept Allen from leaving Arkansas, which history validates as a wise decision.

"I didn’t want to be a crusader," he commented in his book. "I kept thinking, ‘Why me?’ It’s tough to play ball when you’re frightened."

Tough, but not impossible, as Allen proved with an exclamation point. Despite being five years younger than the league's average age, the 21-year-old batted .289/.341/.550 and led the circuit with 33 homers -- a club record that stood for 35 years -- and 12 triples, 97 RBIs and 299 total bases.

“If I’m going to die, why not die doing what God gave me a gift to do," Allen wrote. "I’ll die right there in that batter’s box without any fear.”

Despite the rocky early reception, most Travelers fans came to know the type of player Allen was and rewarded him in kind, voting him the club's MVP at season's end. The conclusion of the season also brought a close to Allen's Minor League career.

He earned his first taste of The Show with the Phillies in September and kicked off his Hall of Fame career by winning National League Rookie of the Year honors the following season. Over the next nine years, the man known as "Crash" cemented himself as one of baseball's most feared sluggers.

Between 1964-72, Allen played with the Phillies, Cardinals, Dodgers and White Sox and averaged 30 homers and 94 RBIs a season while putting together a slash line of .298/.386/.550. He made five of his seven All-Star appearances and won the 1972 American League Most Valuable Player Award with the White Sox. Allen ended his career in Oakland following the 1977 season.

Allen was voted into the Hall of Fame via the Classic Baseball Era Committee as a member of the class of 2025, but, unfortunately, he wasn't around to see it. He passed away at age 78 in December 2020 after a lengthy battle with cancer.

Despite a stellar career marked by misunderstandings and controversies -- some of his own doing -- Allen learned to let go of whatever grudges he might have held, many of which began with his initial experiences in Arkansas.

"All I know is I played ball hard -- the only way I know how. So you've got to go ahead and live with it," he told The Evening Independent in 1982. "I have no regrets. ... I don't have anything in my heart against anybody. And I hope nobody has anything against me."