Rays' pitching secret? It's surprisingly simple

Late last August, Cody Reed reported to the visitors’ clubhouse at Yankee Stadium for his first day of work with the Rays and sat down to meet with pitching coach Kyle Snyder and bullpen coach Stan Boroski. They presented Tampa Bay’s newest left-handed pitcher with a binder full of charts, data and reports, information dating back to his time at Northwest Mississippi Community College in 2013.

The binder covered everything from his amateur career, back when he thought the Rays might draft him, through his time in the Royals’ Minor League system and on the Reds’ big league staff. At every level, it was clear to Reed that the Rays had done their homework.

But Snyder and Boroski did not force Reed to dig into the data in front of him. They didn’t tell him everything he’d done wrong before or anything he’d have to change in the future. Armed with all kinds of information from the Rays’ front office, their guidance was actually about as basic as it gets.

“They were like, ‘Hey man, your stuff is this good. Just throw it over the plate,’” Reed recalled. “And that was probably about as easy as any advice I’ve ever gotten. I was like, ‘Well, I can throw it over the plate for sure.’”

They were like, ‘Hey man, your stuff is this good. Just throw it over the plate.’ And that was probably about as easy as any advice I’ve ever gotten.

Run prevention will always be the foundation of everything the Rays do. The defending American League champions parted with Charlie Morton and Blake Snell over the offseason, but they’re confident they have the pitching and defense necessary to get back to October. And it’s hard to argue with a team that has posted the AL’s best or second-best ERA each of the past three years.

How do the Rays keep doing it, though?

In their initial meeting, Snyder and Boroski offered Reed two things: complex information and simple messages. Those are the keys the Rays use to help unlock the natural talent they’ve identified in their pitchers, from Opening Day starter Tyler Glasnow to the seemingly endless parade of shutdown relievers marching out of the “Stable” that is their bullpen.

“They actually have concrete data to make you good at pitching,” Glasnow said. “They're not just shooting in the dark. They're telling you: 'If you do this, you will succeed.' And chances are, that usually happens.”

Simple messages

The details differ from pitcher to pitcher, but pretty much everyone on the Rays' staff has a story like the one Reed told. Glasnow might be the best example.

The 6-foot-8 right-hander possesses as much ability as any pitcher in the game, yet he floundered in Pittsburgh at the start of his career. On Aug. 1, 2018 -- a day after the Pirates traded him, Austin Meadows and prospect Shane Baz to Tampa Bay for Chris Archer -- the Rays asked Glasnow to start against the Angels at Tropicana Field.

There wasn’t much time to fill Glasnow's head with new thoughts or get him up to speed on how the Rays went about their business. Which was fine, because Snyder had no intention of doing so anyway. He wanted Glasnow to keep it as simple as possible.

“The first start was, like, just, ‘Middle. Aim to bigger areas,’” Glasnow said. “I had my change of scenery. And I was like, ‘OK, this is completely new.’ I didn’t even have time to think, and I kind of felt like I got back to myself.”

Over his first 12 innings with the team, Glasnow allowed three runs and walked only three batters while striking out 20. The Rays encouraged Glasnow to throw four-seam fastballs up in the zone, freeing him from the Pirates’ sinker-heavy, corner-painting approach. But Snyder said he mostly just made sure Glasnow would “understand the cost of a ball” and realize that the strike zone is larger than he might have thought.

“It's the right information. It's not like they give you any more or any less,” Glasnow said. “It's just like what they're telling you actually makes sense.”

The Rays kept sharing simple messages and let Glasnow flourish, further boosting his confidence. Unleashing the elite fastball and curveball that made him a top prospect, he has gone on to log a 3.21 ERA with 237 strikeouts in 35 starts for Tampa Bay over the past three-plus seasons.

Tampa Bay’s approach was eye-opening to Glasnow, who said teams spent years trying to support pitchers by passing on advice that had worked for others rather than addressing their specific needs. But the Rays don’t speak in generalities. They personalize their information, helping players understand specifically how their pitches play and what makes them effective at their best.

“It’s just a relentless pursuit of doing what you do best and trusting that it's going to be good enough to get hitters out,” Boroski said.

It’s just a relentless pursuit of doing what you do best and trusting that it's going to be good enough to get hitters out.

With one of the league’s smallest payrolls, the Rays rely on their ability to find value where others don’t. That’s one reason they’re consistent in their messaging with everyone, from a top-of-the-rotation starter like Glasnow to pitchers brought in via seemingly minor moves. Last year, for instance, Tampa Bay had three non-roster invitees make the Opening Day roster and nine who spent time on the active roster. Three of those non-roster players -- Josh Fleming, Ryan Thompson and Ryan Sherriff -- pitched in the World Series.

The Rays have shown a knack for producing narratives like that. With their pitching staff, it’s rarely a question of if there will be another arm who rises to the occasion. It’s more a matter of who and when.

Hard-throwing Stetson Allie, a non-roster invitee to Spring Training, said he heard nothing but praise from the organization and woke up every day thinking, “I can’t wait to come to the ballpark and learn something.” Non-roster left-hander Dietrich Enns, who went from independent ball to the Rays’ taxi squad last season, said their coaches created a supportive environment where players knew they’d get an opportunity no matter where they came from.

Left-hander Jeffrey Springs, acquired from the Red Sox just before camp opened, said the Rays harped on “rushing to two strikes” and showed him data without overwhelming him. One change they recommended was throwing his breaking ball more -- not because of any issues with other pitches, but because they identified it as being better than Springs himself might have realized.

“It just kind of gives a little bit more confidence in the ability that, hey, it is good. They're looking at it. They're supporting it with numbers. Numbers don't lie,” Springs said. “I think the biggest thing for me has just been, 'Hey, I've got good stuff. Throw the ball over the plate and attack hitters.'”

It has worked a lot lately with pitchers like Glasnow, Thompson, Sherriff, Oliver Drake, Chaz Roe, Pete Fairbanks and perhaps now Reed.

Last Sept. 1 -- on his second day with Tampa Bay, one day after his initial meeting and eight days after Cincinnati designated him for assignment -- Reed pitched two scoreless innings with two strikeouts against the Yankees. He made only one more appearance before a finger issue ended his season, then he earned a spot in the Rays’ Opening Day bullpen after a standout Spring Training.

If it all comes together for Reed, well, a pitcher discarded by another team finding a new home and a new level with the Rays would be a familiar story.

Fairbanks had two Tommy John surgeries on his right elbow and a 9.35 ERA in the Majors by the time the Rays traded for him on July 13, 2019. The 27-year-old right-hander has refined his game since then, improving the carry on his high-octane fastball, and he’s now one of the Rays’ top high-leverage relievers after posting a 2.70 ERA with 39 strikeouts in 27 outings last season.

The night he was dealt from Texas to Tampa Bay and assigned to Triple-A Durham, he got a call from Snyder. You can probably guess how that conversation went.

“He said, ‘Hey, we think you have really good stuff, and we think we can use it in a way that’s more beneficial to you,’” Fairbanks said. “And then I get to Durham, and [pitching coach Rick] Knapp’s like, ‘This is your chart. This is what you do. The arm talent is elite. Now let’s just throw it over the plate.’

“That's like pitching in a nutshell: Get ahead and make them chase something they don't want to hit. And when you get guys that do it really well, you have a very successful pitching staff, I feel like.”

The numbers game

The Rays’ front office has developed a reputation for its analytical savvy. That was true a decade ago under Andrew Friedman, and it remains true under general manager Erik Neander.

“When everybody thinks about Tampa Bay and pitching, the first thing you go to is analytics,” catcher Mike Zunino said recently. “We're very advanced when it comes to that.”

Snyder and Boroski are obviously fluent with the advanced information available to them. Boroski is the longest-tenured member of Tampa Bay’s coaching staff, now in his 10th full season as bullpen coach. He learned from Josh Kalk, formerly a Rays analyst and director of pitching research and development who now works for the Twins. Kalk, Boroski, Neander and assistant director of pitching development Winston Doom also helped Snyder, who took over as the big league pitching coach following the 2017 season, get familiar with the data.

Sifting through that information takes a lot of work from a lot of people. For a report like Reed’s, Snyder and Boroski were pulling from amateur scouting reports in their archives, professional scouting reports from Kevin Ibach’s department, their analytics staff and other sources.

But simply having that material isn’t enough. Every front office has access to information. It’s incumbent upon people like Snyder, Boroski, Doom and process/analytics coach Jonathan “J-Money” Erlichman to chip away at the data and find the core points that can help the Rays' pitchers get better.

“The information that Kyle and Stan have access to, what Winston does, all of our pitching guys, it's a lot. There is a lot of information,” manager Kevin Cash said. “Certainly I can't process and understand all of it. But those guys have studied it themselves to where they have just a knack for breaking it down.

“We could throw five, six, seven different things at [the pitchers], but I don't know how beneficial that would be to their time, their career in that given moment. So that's what makes Kyle and Stan very special in that they're able to just condense everything and pretty much cherry-pick what they value as the most important and really harp on that.”

It’s like an iceberg. Pitchers might see only a small portion of the available information, the part they need to succeed, but there’s much more supporting it beneath the surface. And that step of the process, Zunino said, might actually be what sets Tampa Bay apart. Snyder sounds like a teacher when discussing his presentations: breaking down broader points into sound bites, incorporating visual aids to speed up learning curves, using evidence to take opinions out of the equation and so on.

“You can go find just about anything with the resources that a Major League club has, so I wouldn't say it's necessarily the amount,” Fairbanks said. “I would say it's more of the streamlining and the simplification and the taking all the prep that Kyle does, that Stan does, that Winston and J-Money do. It's taking all that prep and then giving it to you in just the bite that you need to go out and try to perform at your highest level.”

That process starts with building relationships to understand what each pitcher values and how much he can handle. Diego Castillo has a long enough history with Snyder, for instance, to know that his coach will bring something to him only if it’s important enough. Meanwhile, Fairbanks wants everything he can get. Zunino is the same way, preferring to take the pressure off pitchers so they can think about executing pitches, not processing information, on the mound.

The Rays don’t employ a one-size-fits-all philosophy, Snyder said, besides imploring pitchers to throw strikes and get to a two-strike count as quickly as possible. Beyond that, their approach is player-centered: They recognize what each pitcher does best, which they can typically tell by identifying what each does most consistently, and revolve everything around that.

“Emphasizing strengths, letting these guys know how good they really are, why they're good, is always cooked into that,” Snyder said. “Just recognizing what makes them good. It seems simple, but that’s the key, is getting through to them what that is. … And hopefully when you deliver that message, there’s some positive results that follow early and you gain some traction with it.”

One reason Snyder sticks to simple messages at first, he said, is that there’s always time to dive deeper. This is an era of player improvement. The Rays will recommend changes in pitch usage, location, grips, arm slots, delivery mechanics and positions on the rubber. It’s difficult to pigeonhole players because, with the right instruction, they are constantly changing for the better.

“These guys are going to evolve,” Snyder said.

Take Archer, for example. He admitted he wasn’t as open to analytical advice in his first stint with the Rays, but upon his return, he asked, “Hey, what’s going to make me the best pitcher possible for this team?” Snyder and the rest of the staff dug into his arsenal, and they spent the spring working to create the best possible version of Archer’s changeup as a complement to his fastball and slider.

“That kind of opened the door for the analytics department to share with Snydes, and then Snydes put it into English for me to understand,” Archer said. “Because some of that stuff is deep. But it's huge. That's the way the game is going.”

Consider Glasnow, for another example. A year ago, he was a two-pitch pitcher with a negligible changeup. But as he showed on Opening Day, Glasnow now has a legitimate third weapon in his slider. These days, new pitches like that are created in a lab.

Or, more accurately, “The Lab” -- essentially a special bullpen outfitted with TrackMan tracking technology and high-speed cameras. There’s one set up between Fields 3 and 4 at Charlotte Sports Park in Port Charlotte, Fla., and another at Tropicana Field. While developing his slider, Glasnow threw a heavy bullpen session in The Lab under Snyder’s watch.

They consulted the data and video after every pitch Glasnow threw, tinkering with grips and different ways of throwing it to figure out what worked and what didn’t. The pitch evolved even more during Spring Training, at one point blending in too much with his curveball before finally taking the shape they desired. In roughly two months, the pitch went from a non-factor to a devastating breaking ball Glasnow leaned on in his first career Opening Day start.

“I was working on a slider all offseason and I didn't really get much out of it, just because it's hard to keep it consistent. Like, I didn't really know what I was doing with it,” Glasnow said. “And then I had one bullpen session, and it was like, 'OK, now I have a plan.' It just makes everything so much easier.”

So “trust your stuff and throw it over the plate” might sound like an overly simple starting point, but the Rays often target pitchers with enough natural talent to succeed doing exactly that. And if they can improve from there? As Boroski put it: “If you do one thing really well, you have a chance to be good. If you do two things really well, you have a chance to be great.”

If you do one thing really well, you have a chance to be good. If you do two things really well, you have a chance to be great.

The Rays’ charge is to find what their pitchers already do well enough to be good, give them that chance to be great -- and put them in the right position to show it.

“Typically, if there's a guy that comes over, there’s more than just one reason that he's here,” Snyder said. “That's also something that we stress every spring: ‘You guys are here for a reason. You do something most people don't.’”

Clockwork arms

Early in Spring Training, catcher Blake Hunt -- one of the prospects acquired from the Padres in the Snell trade -- made an astute observation while watching live batting practice.

“There’s no conventional arms,” Hunt said. “I don’t feel like any lineup that’s going to go through this big league staff is going to feel comfortable. Every guy has their own look. And then as soon as you go through a lineup once and a lineup does get comfortable, boom, new look.”

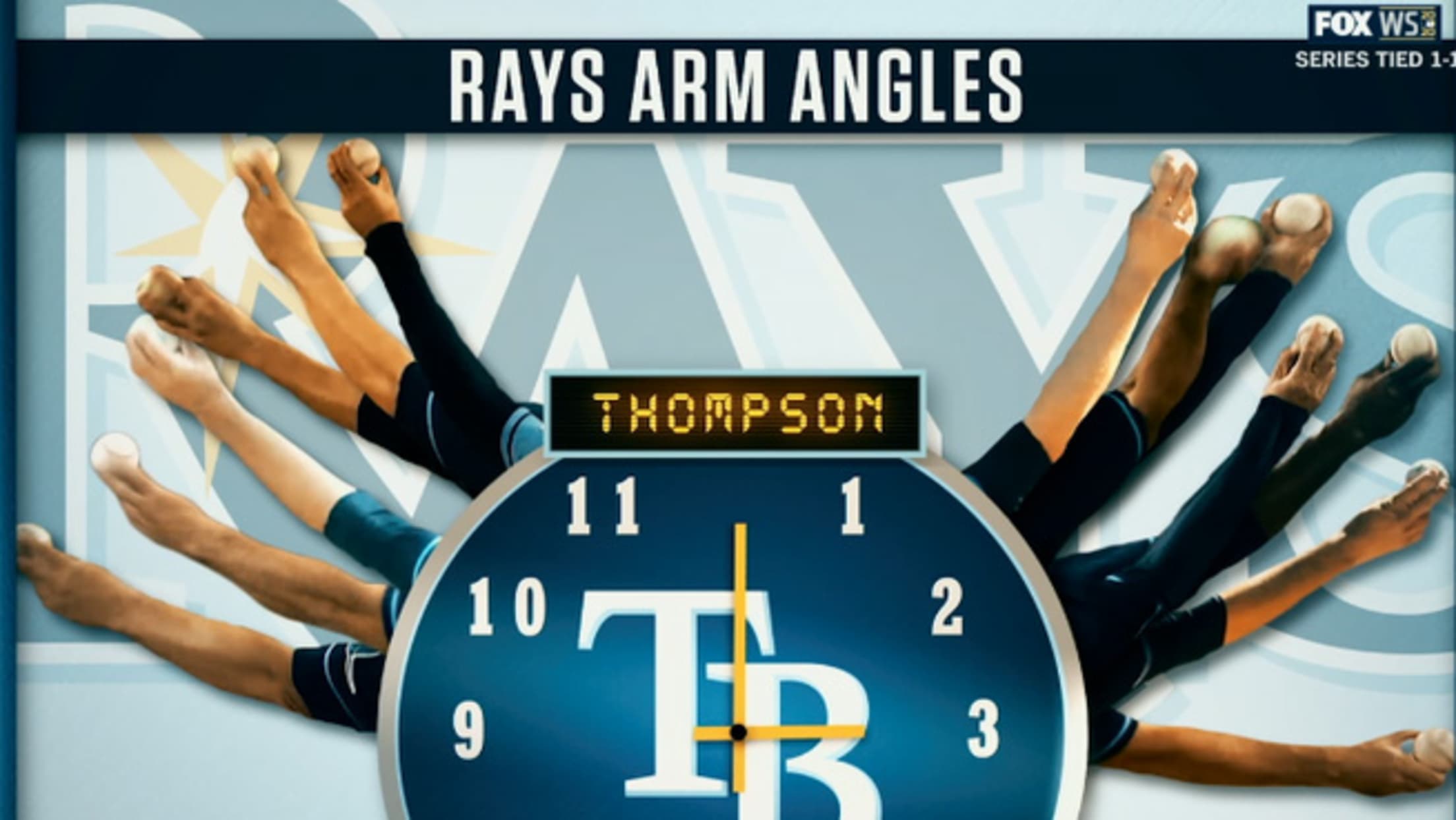

This part of the Rays’ pitching attack earned a lot of attention last October, when they stormed through the postseason by baffling opponents with a bunch of wildly different looks. A few days after the World Series, Snyder said, somebody sent him the graphic that ran on the FOX telecast depicting their pitching staff’s arm angles like the hands of a clock.

“I think there's a rhyme and reason for why we do things how we do,” Zunino said. “We can go almost multiple games and not show teams the same look.”

Maybe it’s a byproduct of the Rays’ need to be creative, but they clearly understand the impact that variety has had. There’s value in finding pitchers who do something at an elite level, sure, and there’s even more in deploying them alongside pitchers who do something completely different at an elite level.

“You can run out seven guys in a row that throw 98,” Boroski said. “But if it's a very similar 98 with very similar movement characteristics, then it's only going to be effective for so long because it's like seeing the same guy.”

You don’t run the risk of seeing many similar guys on the Rays' staff. It is full of outliers, pitchers at the extreme end of one category or another. Consider Tampa Bay's starting pitchers to begin the season.

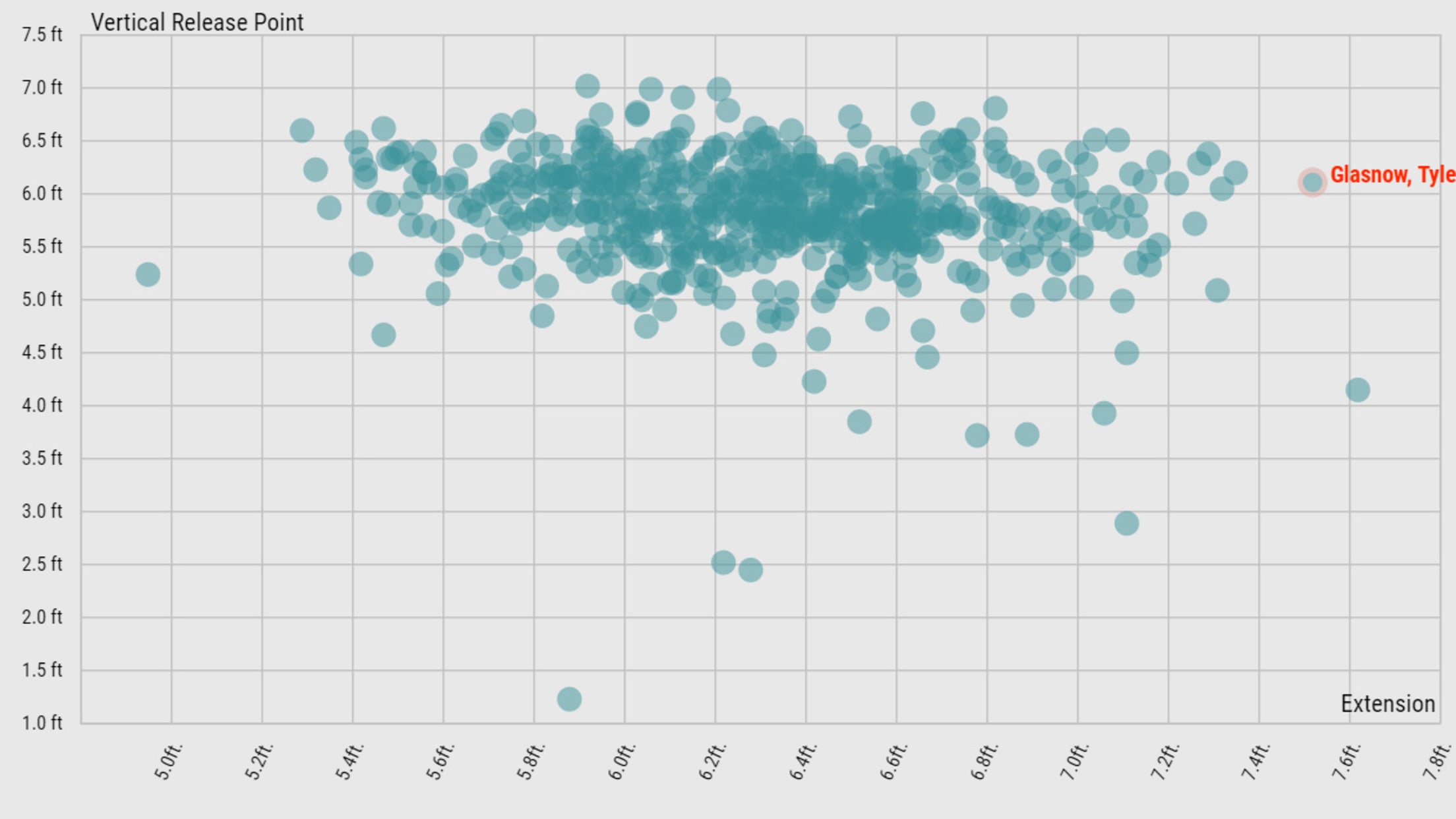

• Glasnow recorded the highest average extension on four-seam fastballs last season: 7.7 feet, 1.3 feet higher than the MLB average. Meanwhile, no pitcher with at least 300 innings from 2018-20 recorded a lower average exit velocity than Ryan Yarbrough, the “king of weak contact.” They began the season as the Rays’ Nos. 1 and 2 starters, forcing opponents to prepare for two extremes on consecutive nights.

• The three veterans brought in as free agents all get it done in different ways than Glasnow, Yarbrough and each other. No starter uses his curveball more than Rich Hill, who averaged an MLB-high 19 inches of horizontal movement on his curve last year; Morton was second, at 17.9 inches. Archer gets outs with his four-seamer and sharp slider. Michael Wacha's changeup produced a 40.8 percent whiff rate last year, nearly 9 percent higher than the league average.

“It's probably something that just organically happened,” Snyder said. “I don't make the decisions on the guys that we bring in, but we've always stressed that there's probably a benefit to some push-pull, some contrast, not just in handedness but in how guys arrive, and capitalizing on that is something we should probably look to do. And I think we've done that.”

It’s even more pronounced in “The Stable.” Consider the relievers currently in the Rays' bullpen.

• In the late innings, Fairbanks fires high four-seamers and swing-and-miss sliders, while Castillo misses barrels with his sinker and misses bats with his slider. Fairbanks had the third-highest vertical release point in baseball last year, at 6.8 feet.

• Nobody in baseball throws a slider with more horizontal movement than Roe. Among right-handers, only Tyler Rogers and Steve Cishek throw from an angle as low and wide as Thompson. Collin McHugh relies on his ability to spin breaking balls. Andrew Kittredge gets grounders with his sinker and slider.

• Reed throws power stuff from the left side. Last year, Springs produced the Majors’ highest whiff rate on sinkers (39.8 percent) and the second highest on changeups (52.8 percent).

“It's such a wide array of arms and what everybody does that, while you might have some that are similar, nobody's quite the same,” Fairbanks said.

But the Rays’ ability to get the most out of their pitchers, conventional arms or not, remains the same.

“It's amazing what our pitching guys find and what they deem valuable, and it's just created a fine-tuned machine with guys they bring in performing,” Zunino said. “And then the next wave of guys come in, they do the same thing.”