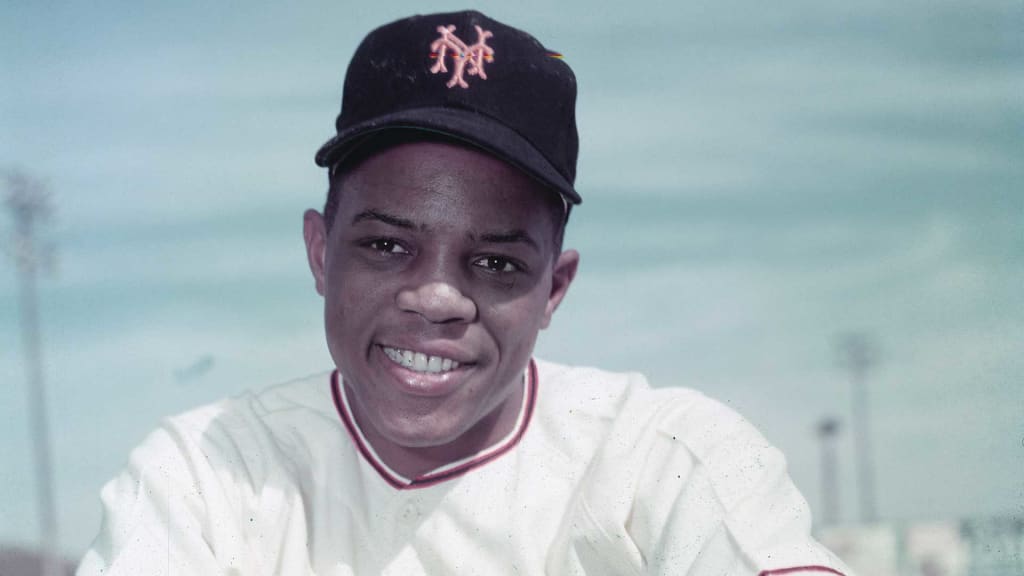

SAN FRANCISCO -- Hall of Famer Willie Mays and longtime San Francisco Chronicle baseball writer John Shea collaborated on Mays’ new memoir, “24: Life Stories and Lessons from the Say Hey Kid,” which was released Tuesday.

Shea, who first approached Mays about this project 15 years ago, spent over 100 hours with the Giants legend and interviewed over 200 people for this book, unearthing a trove of new stories and information about one of the most transcendent stars in baseball history. We caught up with Shea to discuss the memoir, The Catch, Mays’ relationship with Jackie Robinson and parallels to Mike Trout.

This conversation has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

MLB.com: How did you come up with the structure of the book, 24 chapters framed by a life lesson from Willie?

Shea: That really evolved. This was extensive research and sort of investigating Willie's life and career through his words, and the words and eyes of those among the 200-plus I interviewed. The format is unlike any other format I've ever seen, but it's real cool to present Willie’s voice in a different typeface and sort of allow for others to supplement his stories and for me to put a ball on the tee for him to hit out of the ballpark. That was a cool job to be the storyteller and historian for all these people who lived these lives in and out of baseball, telling stories and allowing me to write history that maybe hasn't been written before.

MLB.com: It seems like Willie understood that he was an entertainer as much as a ballplayer and developed his own style to please fans, inventing the basket catch and wearing a cap that was a little too small so it would fly off when he ran. Can you think of any current Major League player that has that type of flair?

Shea: I think that flair is expressed after a successful moment like a home run. After a great play, you can kind of show off a lot more than you were able to in Willie's time. But Willie's flair came through during the play. Willie’s way was with exuberance and joy and laughter. He wanted to make tough plays look easy and easy plays look tough, just to entertain people so that they could come out and watch the team the next day.

If you look at the road attendance, eight times in the ‘60s, the Giants had the best road attendance in the National League. Mays played every day. That stat with 13 straight years of 150-plus games is a record that'll never be broken. Not only was he the greatest all-around player, but he was among the most durable, and without a doubt, the most entertaining. That's quite a package. It's not just the five tools, it’s all these other tools that just set him apart like nobody else.

MLB.com: We’ve all seen footage of The Catch, and yet there's still so much debate over the details of the play, such as how far Vic Wertz actually hit the ball. Nowadays, we'd have all those metrics thanks to Statcast, but do you think not knowing the particulars of the play has added to its lore, in a way?

Shea: Tom Tango [stats analyst] was very helpful with all that stuff, where I tried to set Willie apart based on today's games, metrics and analytics. He was very helpful, but even he couldn't determine how far [Willie] ran, or how long the ball was in the air, or how long the throw was. All we know is that it was six-and-a-half seconds from contact off bat until the release of Willie's throw.

Even that's not exact because the timing in the film might not have been in real time. Unfortunately, we don't have a camera on Willie when he took off, so we don't know exactly how shallow he was playing. He said he actually moved in because Don Liddle was pitching, so he was expecting singles up the middle rather than a ball over his head. But sure enough, it went over his head, and he ran it down.

It's fascinating to me that we’ve seen it so many times but we don't know the exact data of the play, even though we have it on film. As [Tango] said, maybe it's best to be left alone because we can see it. We saw how great it was.

MLB.com: And it's incredible to think that Willie doesn't even consider it his best catch.

Shea: It's funny, but in large part, his top offensive performances came in San Francisco. The [16th-inning] walk-off home run against [Warren] Spahn. The four home runs in Milwaukee. The home run in the final regular-season game in ‘62 to force that best-of-three [playoff] against the Dodgers. Obviously, his 3,000th hit and his 600th home run, all the big milestones happened in San Francisco.

And most of the great defensive plays, it seems, happened in New York. So, [his top catch] happened in ‘52, the Bobby Morgan play where he dived and hit his head on the concrete wall at Ebbets Field and got knocked out. He maintains that's his best catch.

MLB.com: It's interesting that Willie wasn't immediately embraced by fans in San Francisco after the Giants moved west in 1958, partly because he was living in the shadow of Joe DiMaggio. How long did it take for fans in San Francisco to warm up to him, and how would you describe his relationship to the city today?

Shea: That was only because of the great Joe DiMaggio. Everyone had memories of him. What people don't understand is Joe was Willie’s guy. He tried to emulate him because Joe could do it all, the five tools. Willie looks up to this guy, so he's stunned. He was cherished in New York. He comes out to San Francisco, and they have [Orlando] Cepeda in ‘58 and [Willie] McCovey in ‘59. San Franciscans were much quicker to accept those two guys than the out-of-town superstar who became famous in New York.

But [Willie] tried not to let that bother him, because he still put up great years. I'm pretty certain that a majority of people took to him right away. It was just so mysterious and odd that some people didn’t. That was the story of the day at the time, which, when you look back, is just ridiculous. All we know now is the great Mays, 24 Willie Mays Plaza. The first statue at the new park in 2000, put up by [former Giants owner] Peter Magowan. The retired number and the cable car, No. 24. It's such an iconic number, and it represents Willie.

MLB.com: Bill Clinton had a great quote where he said Willie made it absurd to be racist, yet he still experienced housing discrimination in San Francisco and faced jeers and taunts from fans in the Minor Leagues and beyond. Jackie Robinson, at one point, felt that Willie could have done more for civil rights, but what’s your view on the role that Willie played in advocating for his community in his own way, even if he wasn’t an activist?

Shea: Jackie expected more of him because he was the guy. But Willie told me he just wasn't Jackie. He wasn't able to do the things that Jackie did. Let's not forget that Jackie was raised in Pasadena and went to UCLA. He marries Rachel, and he spends time in the Army and Negro Leagues. He’s the first to sign with a Major League team, but he spends a full season in Montreal, and only then does he report to the Dodgers. This is a well-seasoned person who has a wonderful background and temperament and is the perfect guy to do what he did.

Willie Mays is 20 years old, a year removed from high school graduation, and he’s playing center field at the Polo Grounds. He didn't have the type of family that Jackie did. Willie was alone a lot. His teenage aunts raised him. His dad helped when he could, but his dad traveled and had two or three jobs. He has great memories of his dad, but he wasn't around all the time. So, Willie admits that he couldn't do the things Jackie did, especially because his dad told him not to do those things. Not to talk too much and just keep quiet and do your job. Willie wasn't raised that way.

But Willie, obviously, was a difference maker. Maury Wills, who knew Jackie very well from their Dodger connection, was very [clear] in suggesting Jackie was wrong. [Peers and observers] gave anecdotes and reasons why Willie actually was a motivating force for the black cause and was a big help during the civil rights movement. But he didn't do it Jackie's way.

MLB.com: Mike Trout is most often compared to Mickey Mantle, but I was really fascinated by the parallels that you drew between him and Willie, just because they were these two great players who were probably hurt multiple times in MVP voting because of their all-around skills.

Shea: Willie hates it when people try to compare other people to him because he saw that it might have affected Bobby Bonds, who was supposed to be the next Mays. That was way too much pressure to put on anybody. So he didn't want to see comparisons to him, and that includes Trout or [Mookie] Betts or anybody else.

But it is interesting to note that Trout has more second-place finishes than first-place finishes. He has three MVPs and four seconds. That's seven times that he was first or second in the voting over an eight-year stretch, which is hard to believe. But after talking to Tango and Eno Sarris and Bill James, you walk away thinking that [Mays] could have won eight to 11 MVPs instead of the two that he won based on today's analytics and the way teams and statisticians value players. Long before we knew what [Wins Above Replacement] was, Willie was the master of WAR.

MLB.com: Have you spoken to Willie since baseball operations were suspended because of the pandemic? How is he dealing with life without baseball?

Shea: I was over at his house [Saturday] for a while just to visit. I had to distance. He's 89, so this is kind of a bummer for him. This is his time to be at the ballpark and engage with players. The whole banter thing is something he loves. He doesn't get to do that. He's susceptible at his age and can't go out much. It's unfortunate for him at this time in his life. He's got so many friends, though, and so many people who love him dearly and check in on him. It's kind of a hard time for him, but it'll make the return of baseball that much sweeter to have Mays back on the premises, inspiring young players, greeting fans and hanging out at baseball games again.