Aníbal Sánchez shouldn't be here.

Not at nearly 36 years old, which he'll be on Feb. 27. Not with a fastball that averages a mere 90.3 mph, an eighth-percentile velocity that rates among the slowest of any regular starter this season. Not among the living legends in this World Series like Justin Verlander, Max Scherzer, Gerrit Cole, and Stephen Strasburg, or even very good next-tier starters Patrick Corbin or Zack Greinke, and especially not after age 31-33 seasons that went like this:

Age 31 (2015) -- 4.99 ERA for Tigers

Age 32 (2016) -- 5.87 ERA for Tigers

Age 33 (2017) -- 6.41 ERA for Tigers

Combine those, and the 5.67 ERA he posted from 2015-'17 was the highest among any pitcher who threw at least 250 innings during that span. That's how careers end, especially when his age-34 season began with his being released by the Twins in Spring Training last March, less than a month after having signed with them.

But he is here, and he'll be starting Game 3 of the World Series on Friday night, throwing the first World Series pitch in the nation's capital since 1933, and with a chance to turn a commanding 2-0 Nationals lead into a nearly insurmountable 3-0 advantage. In two postseason starts so far, Sánchez has allowed just a single run in 12 2/3 innings, taking a no-hitter into the eighth inning of the first game of the NLCS.

So, as he prepares to face a Houston lineup that was legitimately one of the best in history this season, even if they haven't quite acted like it in October ... how? How does a soft-tossing mid-30s righty who seemingly bottomed out not only find himself in such a big spot, but to get there pitching so well that his team is thrilled to see him take the mound, not worried?

The answer is easy. It's how he got there that's hard. Sánchez, both this year and over the last two seasons -- he had an impressive 2.83 ERA in 136 2/3 innings for the Braves after the Twins released him last year -- has done a better job of avoiding hard-hit contact, the most damaging kind of contact, than any other starter in baseball.

Lowest hard-hit%, 2018-19 (starters, min. 300 batted balls)

27.5% -- Aníbal Sánchez, ATL/WSN <---------------

28.2% -- Ryan Yarbrough, TB

28.3% -- CC Sabathia, NYY

29.1% -- Noah Syndergaard, NYM

29.7% -- Jacob deGrom, NYM

(A "hard-hit ball" is one that's hit at 95 mph of exit velocity or more, and it's a big deal. Over the last two years, the Majors have hit .533 with a 1.090 slugging percentage on balls hit 95 mph or harder, and a mere .219/.259 on balls hit 94 mph or below. That's true for Sánchez, too, who has allowed a .544/1.149 BA/SLG on balls hit 95 or harder, and just .195/.238 on balls hit 94 and under. This isn't rocket science: Hit the ball hard, and damage will follow.)

It's true in just 2019, too, where Sánchez finished second only to Yarbrough in preventing hard-hit contact. For a pitcher who doesn't miss a ton of bats -- his 18.8% strikeout rate is below the Major League average of 23% -- this is it, right here. About three-quarters of the time that Sánchez allowed contact, he allowed weak contact. It's that skill which has allowed him to succeed.

You could see that in practice in Game 1 of the NLDS, where he allowed 18 balls in play, and just one -- a second-ining Marcell Ozuna flyout -- was hit hard.

But that wasn't the case when he was struggling with the Tigers, as he allowed a 34.1% hard-hit rate over his final three years, compared to the 27.3% he's allowed with the Braves and Nationals. He's gone from that 5.67 ERA with the Tigers to 3.39 with the Braves and Nationals, and he's done it with less velocity on his four-seamer, dropping from 91.8 to 90.3 mph. What's changed? Let's present three possibilities.

1) He's throwing different pitches.

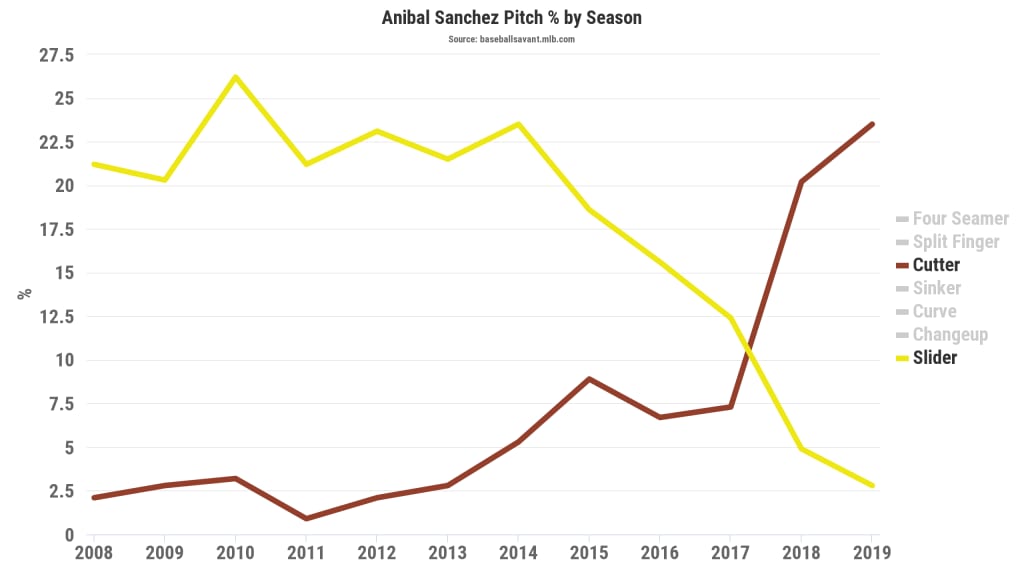

This seems like the obvious place to start, because whenever a pitcher's performance changes that drastically, you like to have something obvious to look to. In this case, Sánchez makes it easy. He all but stopped throwing his slider, and he replaced it with a cutter. We'll share the numbers -- those last three years with the Tigers, it was 8% cutter / 16% slider, and in the last two years, it's 22% cutter / 4% slider -- but this image probably tells the story just as well.

This is only a fraction of his repertoire, of course. Sánchez throws seven different pitches, also including a four-seam fastball, a sinker, a splitter, a curve, and a changeup with the slider and cutter. But the slider is now his least-used pitch, a big departure from his Detroit days when it was his primary pitch aside from his four-seamer.

It's easy to see the appeal. In 2017, his slider allowed a nearly unfathomable .471 average and .882 slugging, making it the second-worst slider season on record, dating back to 2008. Over the last two years, his cutter has allowed a .195 average and a .333 slugging, making it one of the best starting pitcher cutters.

"Stop throwing a poor pitch and throw a better one" isn't exactly revolutionary, but it's worked here. Sánchez's cutter has 4.6 inches more rise than other cutters at his velocity, a top five mark.

"I was working hard those years [in 2016 and 2017], too," Sánchez said the day before his Game 3 start. "But you know what, the result wasn't there. ... I signed with the Twins and I got released, and after that I said, 'OK, whatever happens is going to happen, I'm not going to force anything. I got an opportunity with the Braves and showed that I can still pitch on this level, and now I'm here."

2) He's preparing better, and working well with catcher Kurt Suzuki.

This is hard to quantify, but he's said it enough times that you believe there's at least something to it.

“Two years ago, I was not confident at all. I didn’t prepare at all in between games,” he told the Athletic during Spring Training.

Then look at what he said regarding his 2018 rebound with the Braves.

"I just prepared for my games better," Sánchez told MLB.com before signing with the Nationals last winter. As he told the Washington Post in March, he began studying two hours per day between starts on how to best attack the hitters he'd next face.

There's also some evidence that Suzuki, who was also in Atlanta in 2018 with Sánchez, has played a big part in this.

"That's a big thing for me," Sánchez said in December, referring to joining the Nationals shortly after Suzuki had signed a two-year deal. "Especially because of the way I pitched in 2018, Suzuki was involved in everything. In every change that I made, every sequence that we worked for, Suzuki was really involved."

Suzuki caught 26 of Sánchez's 30 starts this year, though his value might have been higher as an off-season pitching coach rather than an in-game partner; Sánchez performed better with Yan Gomes catching, and it was Gomes who was behind the dish for the near no-hitter in the NLDS.

3) The end of his Detroit tenure might not quite as been as disastrous as it seemed.

In 2017, Sánchez had that 6.41 ERA, which requires no context: It's bad. And yet, if you looked under the hood, there were even at the time reasons to believe he had more to offer. Headed into that offseason, we named him as a possibly "undervalued pitcher," despite the ERA.

When he signed with the Twins the next spring, they echoed many of the same thoughts.

"His analytics on some of the factors [our evaluators] feel are significant were a lot better than his results," then-Twins manager Paul Molitor said. "Obviously, the long ball bit him a lot. A lot of people think it has to do with pitch usage and some other things. But they really liked a lot of the weapons he still has. They think he got away from things that would give him a better chance to be successful."

Right there: Pitch usage, and "analytic ... factors [that were] a lot better than his results. (There was ample evidence that he was one of the least fortunate starters of 2017, helped along in no small part by Detroit's terrible 2017 defense.) Some of this was hiding right there in plain sight.

In some sense, Sánchez is like a righty version of Hyun-Jin Ryu, who relied more on deception, command, and a large repertoire of pitches rather than velocity to turn his 2019 season into a success.

"Last year, I put in a lot of effort to be here today,” he told MLB.com this spring. “When I see my uniform, I feel a blessing. I knew before 2018, I was really, really struggling for my career.”

He's right. For a million other guys, posting three increasingly-poor seasons as he aged into his mid-30s, then getting cut in spring training the next year, would have been the end of the line. That's generally how it works. For Sánchez, he didn't just find a way to stick around. He's found a way to succeed. When he takes the mound in Game 3, it's not because the Nats couldn't find anyone better. It's because they found exactly who they wanted. After four teams in the last two years, he's in the right place.