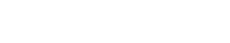

MLB.com is republishing this story after Willie Mays passed away on Tuesday at age 93.

There is a lot of GOAT talk these days, so much of it about Michael Jordan, because of ESPN's ongoing 10-part documentary “The Last Dance.” Jordan brings to mind the line that was always used about Sugar Ray Robinson, who was once called the best pound-for-pound prizefighter who ever lived. That is what Jordan was in basketball, and what Willie Mays was in baseball. Mays turns 89 on Wednesday, and we will celebrate his life and his career just like we do every year at this time, and with good reason. Willie Mays is the GOAT -- the Greatest Of All Time.

Willie Mays, 1931-2024:

- Willie Mays, a baseball giant, dies at 93

- Loss of Mays leaves Giants heartbroken in Chicago

- 'My heart is on the floor': Baseball world reacts to Mays' passing

- Rickwood Field game has new meaning: Mays will 'be watching over'

- Timeline of the Say Hey Kid's legendary career

- Griffey grateful for time with Mays, 'the godfather of center fielders'

- Cutch remembers Mays: 'He was a pioneer for the game'

- 24 amazing Willie Mays stats

- Willie Mays' best moments

- Mays always knew he'd make The Catch

- Willie Mays learned the game in the Negro Leagues

- Mays, Clemente in same outfield? It happened

- The thing that stopped Aaron-Mays OF? $50

- Mays' pure joy for baseball made him the GOAT

- The day Mays nearly sat out but hit 4 HRs instead

- Mays' last dance in NY came with '73 Mets

Perhaps it is fitting that when Jordan tried to be a professional baseball player, he played for the Birmingham Barons in 1994. One of the places where it all began for Willie Howard Mays Jr., out of Westfield, Ala., was with the Birmingham Black Barons in '48.

“He is still unlike any other player I have ever seen,” broadcaster Tim McCarver said on Monday. “Nobody ever more exuded the way the game should be played, and in a joyful way, than Willie Mays. Don’t get me wrong -- plenty of other guys had joy. Just not like Willie’s joy.”

Mays left New York far too early, in 1957, when the Giants moved to San Francisco, which meant Mays played too much of his prime in the wind and cold of Candlestick Park. When he came back to New York to play for the Mets, he was too old. So he never had the spotlight and the stage that Mickey Mantle did. He played at the same time as the great Hank Aaron. But Mays was the one. He was the greatest all-around ballplayer of them all.

There was a time in America when the biggest compliment you could pay any athlete in any sport was this: He had some Willie Mays in him.

Even playing over a decade of home games on Candlestick Point, he still hit 660 home runs in the big leagues. He only played in four World Series in his career, three with the Giants and one with the Mets, and he won only one in 1954. He played in 20 Fall Classic games, and in one of them, at the old Polo Grounds in '54, he made what is still the most famous World Series catch of them all, on a fly ball from Cleveland's Vic Wertz.

And then Mays wheeled around and came out of that catch, cap flying off his head and in that moment, throwing.

“You run the dugout,” Mays said to Bob Costas in a 2006 interview, recounting what he had once said to manager Herman Franks. “I’ll run the field.”

There will be so many Mays stories this week. One of my favorites comes from McCarver, who played against the Giants in so much of Willie’s prime in the 1960s. McCarver said that Johnny Keane, who managed the Cardinals to the 1964 World Series championship, had a rule for Cards outfielders: If Mays was on the bases and trying to score on a hit, they were not supposed to throw home, unless he was trying to score the winning run.

“Johnny’s theory was that it was what Willie wanted you to do,” McCarver said with a smile. “He wanted you to think you had a play, he’d make you think it was going to be close, you’d never throw him out, and the guy who hit the ball would always get an extra base.”

McCarver paused.

“I asked Willie one time if he actually did that,” McCarver said. “He smiled at me and said, ‘Well yes, Tim, I did.’”

And in center field? Mays is best described by one of the best baseball lines of all time, from the late Dodgers executive Fresco Thompson: “Willie Mays’ glove is where triples go to die.”

Even in the age of MLB Network and MLB.TV, so much of what Mike Trout -- the best all-around player in the world now -- occurs too late for an East Coast audience. In Mays' time, in the heyday of the Say Hey Kid, he was hardly available to the rest of the country except when they would be lucky enough to see him on NBC’s Game of the Week. Or in the kind of World Series the Giants played against the Yankees in 1962, a Series that went the distance and ended with Mays on second after he’d doubled to right, putting Matty Alou on third before Willie McCovey hit a screaming line drive that ended up in Bobby Richardson’s glove.

Mays spent some time as a hitting instructor with the Mets after he retired. I was with him one day in St. Petersburg and asked him the same question I asked Aaron the other day, about regrets. Aaron said his biggest regret was that he never won the Triple Crown.

“I just wished the people who only really saw me when I was old could have seen me when I was young,” Mays said.

We now feel as if we are watching every move that Jordan made. He did what he did in the 1980s and '90s. The best of Mays was in the 1950s and '60s -- in a different world, where not enough people saw him hitting, running, throwing and playing the game with joy. And making everybody else wish they had some Mays in them.

“The operative word,” Tim McCarver said, “being 'some.'”