Game Preparation and Play

The style of play in the Negro Leagues varied greatly from that of white professional baseball. This started with how teams prepared for their seasons to how they played on the field.

SPRING TRAINING

Spring Training, began in the late 1800s with some believing the tradition began when the Chicago White Stockings and Cincinnati Red Stockings traveled to New Orleans, Louisiana in 1870 to set up camp. Others point to a four-day camp held in Jacksonville, Florida by the Washington Capitals in 1888. Regardless of the official origins, by 1900 Spring Training had become the normal practice for the American and National Leagues.

Spring Training was - and is - an opportunity for players to work on their skills and for the team's manager and coaches to evaluate talent that would eventually make the roster.

THE ROSTER

Since around 1910, the American and National Leagues have allowed for their active roster - players eligible to play - to have up to 25 players. In 1921 the 40-man roster went into effect and includes players on the disabled list and players in the minor leagues who signed to a Major League contract.

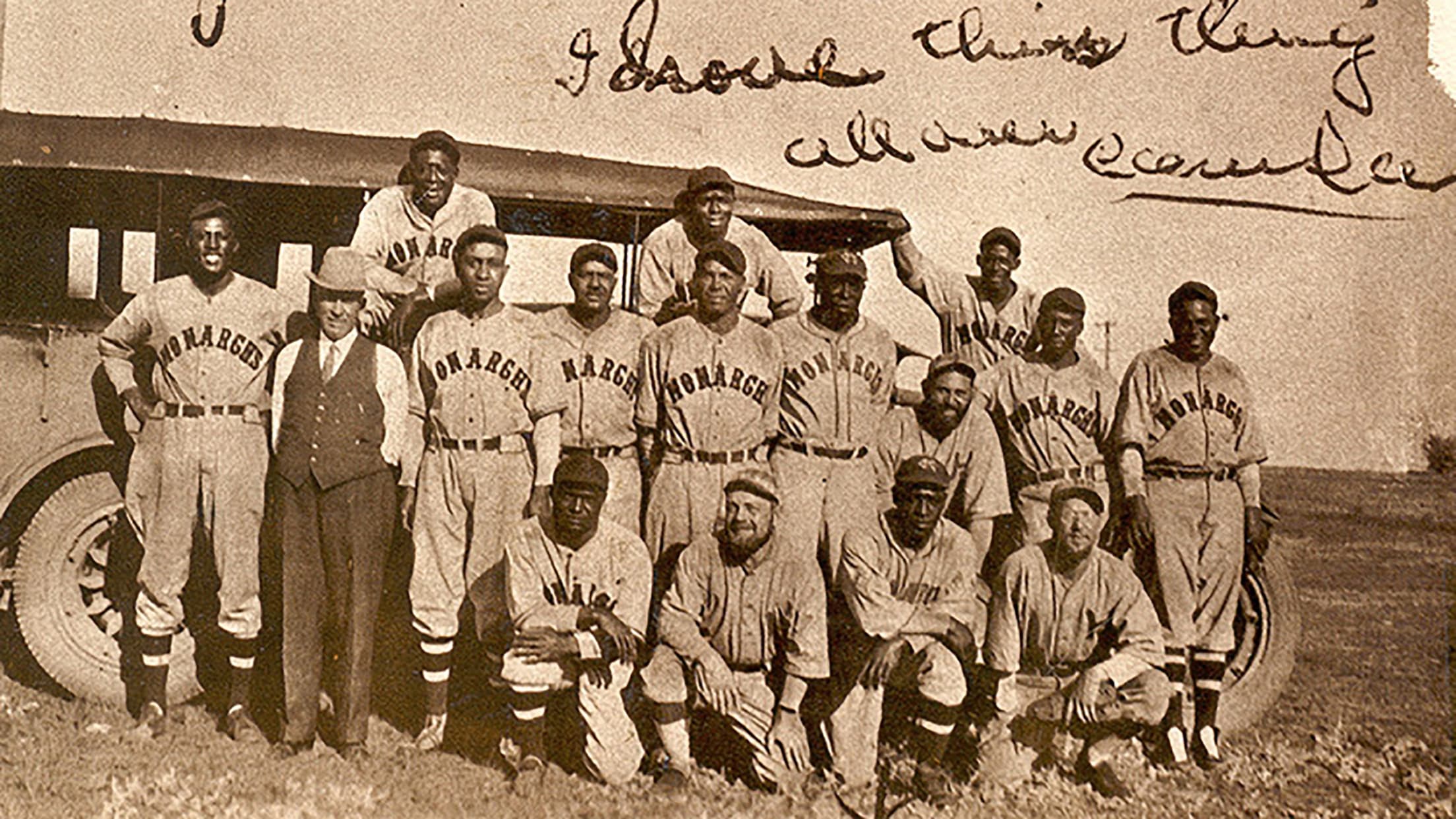

By contrast, Negro League teams carried between 16 and 18 players on their teams, far fewer players than the American and National League teams. This was partially due to the strict budgets of teams and lack of funds to pay for additional players. This meant that Negro League players had to be able to play more than one position, something that happened frequently as the teams traveled extensively and played multiple games in a day. Bill Cash, a catcher for the Philadelphia Stars shared that he played every position but shortstop and pitcher.

Did You Know

The number of players allowed on MLB's active and 40-man rosters was impacted by events taking place in the country and worldwide?

The number of players on both the active and 40-man roster fluctuated due to World War I, the Great Depression and the period after World War II.

In 1945 and 1946 the 40-man roster limit was raised to 48 players to accommodate returning veterans.

From 1986 until 1989 the active roster was limited to 24 to help counter the expense of rising player salaries.

Play Style

During the first half of the 20th century the white baseball game relied on the power of the players. Players focused on hitting the ball out of the park, scoring runs in bunches. The Negro League game was much different. It was a game of finesse. Players manufactured runs with the bunt, base stealing and the hit and run.

With the fast pace of the Negro League game, players on both offense and defense had to be on their toes. While today you will often see players sliding head first, Negro League players never did so. They always slid with their spikes up and out so that the defensive player would not be able to tag or spike them in the hands or arms.

By the same token, the defense needed to be quick, particularly on double play balls. Mahlon Duckett who played second base for the Philadelphia Stars shared that "you had to know how to get that ball, make the play and get out of the way," before a player would take you out with a spike on a hard slide.

When players got on base, they did not like to stay still. They would look for the chance to take the next base either by a steal or attempting to take an extra base on a hit by a teammate. This constant activity on the base paths caused the defense, and pitchers in particular, to really pay attention to what was happening on the base paths.

When Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947, he brought the Negro League style of play to Major League Baseball. Stars' player Wilmer Harris shared that "Jackie took Negro League Baseball to the Major Leagues. There was no such thing as hitting a single and going to second. He made the Major Leagues better and everyone was trying to play like the Dodgers."

On the field the Negro League players were fierce competitors but off the field they were a tight knit crew. They harbored no hard feelings toward one another because each understood that what happened on the field should stay there. This was an attitude that was embraced because off the field they were facing the same obstacles and discrimination.

Did You Know

Negro League players often warmed up in a style called "shadow ball" where players pretended to hit and field a baseball. The players would dive around the field and the players sold their hits and catches so well that the spectators thought they were playing with an actual baseball.

Activity

- In what ways did Negro League baseball differ from professional white baseball?

- How do you see the Negro League baseball style of play reflected in today's game?

Playing White Teams

While Major League Baseball was segregated it was not unusual for white and African-American teams to play against one another. Barnstorming tours for Negro League teams often included games against white semi-professional and professional teams. It was also common for Negro League teams to create a team of all-stars who would also play against all-star teams from the American and National Leagues. In these games the contrast between the National and American League power game and the Negro League style of "small ball" was apparent. Records reflect that the Negro League teams won the match-ups approximately 60% of the time.

OFF-SEASON BASEBALL

There was money to be made during the off-season for Negro League players. Many players would travel to states such as California or Florida or even leave the country and play in Latin American countries in order to continue earning a salary while keeping themselves in baseball ready shape.

Hotels and Negro League teams had an early connection. The first professional African-American team played out of the Argyle Hotel in Babylon, New York so it was not surprising that Negro League teams continued a partnership with hotels during the winter months. Hotels would form Negro League teams that would play exhibition games to attract and entertain hotel visitors.

While not on the field, the players would work in the hotel to earn extra money as waiters, bellhops or in other roles that needed to be filled. Though this arrangement might seem to favor the hotels, the Negro League teams took advantage of the situation. Negro Leaguers who worked and played at hotels did not have to look for work to make up the salary they would lose during the offseason. They could continue to play the game they loved and stay in shape for the next season while pulling in some additional funds from their secondary role at the hotel.

Negro League team owners and leaders also used the opportunity to make business world connections with the hotel patrons by exposing them, and all hotel guests, to the exciting Negro League play style.

Other players traveled to Latin American countries to play during the offseason. Players reported that playing in Latin American countries was an exhilarating experience and one quite different from their time playing in the United States. Philadelphia Stars player Stanley Glenn who played both in Latin America and in Cuba shared that there was "no segregation in Latin American countries." The players there simply respected the talent displayed.

Those players who were not able to play winter ball returned to their hometowns and sought work that would get them through to the next baseball season.

ON THE ROAD

Negro League players dealt with a lot of adversity and encountered many obstacles in their quest to play professioal baseball. From the late 1800s until 1947 they were kept out of white professional baseball due to the unwritten "gentleman's agreement." The racism encountered on the ballfield was amplified when players traveled and played particularly in the Southern portion of the country.

After the 1896 Plessy v Ferguson Supreme Court ruling in favor of separate but equal accommodations, players often had a hard time finding places to eat and sleep.

TRAVEL

Negro League baseball's success, in great part, depended upon a team's ability to successfully barnstorm. Barnstorming is when a team travels to different areas of the country in order to play exhibition games for pay. The more games the teams played, the more they earned. This meant that teams would often play up to three games in a day and sometimes seven or eight game a weekend. In fact, Negro League teams could play close to 300 games in a season between their designated league games and barnstorming tours. What makes this fact even more astounding is that the games were not always played in the same location. Once a game would conclude, players would jump back onto their bus and travel to another city to play the next game.

Travel was by bus and players were the ones doing the driving. Players would rotate driving responsibilities to allow for some rest in between games. But this was not ideal. The buses were often old and rickety and tended to be uncomfortable.

Making things more difficult was the fact that players typically had to board the bus without having had the opportunity to shower. The ball fields where they played either didn't have showers or the showers were not available to African-American players. "Don't think you're going to find a shower at the end of the day. There was ballparks there but they wouldn't run the water on for you," shared Philadelphia Stars' pitcher Harold Gould.

In contrast to what the Negro League players encountered, white ball clubs had use of private buses with a hired driver and access to trains with sleeper cars.

ACCOMMODATIONS

Throughout the country, but particularly in the South, hotels were segregated. Hotels that would accommodate African-Americans were scarce leaving the Negro League players, who traveled the country extensively barnstorming, to scramble to find places to sleep. Hotels that would accommodate African-Americans were not places one could sleep comfortably. Players shared how the hotels were bug infested and not cleaned regularly. When asked why they would stay in such unsanitary conditions, players shared that putting up with poor sleeping conditions was better than sleeping on a bus.

However, when hotels could not be found, players were forced to sleep on the bus resulting in restless nights. The players did not allow where they slept or how they slept to affect them. Stanley Glenn of the Philadelphia Stars shared that "America wasn't a very nice place to be south of Chester, Pennsylvania. So we did an awful lot of sleeping in the bus. We didn't seem to mind it very much. Just goes to show you how much we just liked to play baseball."

Players felt most fortunate when strangers within the African-American community in a visiting town opened their homes to provide a place to comfortable place to bathe, sleep and eat. Players relished the chance to take a hot shower and filled their stomachs with food better than any restaurant would provide.

Many restaurants that would serve African-Americans and those that did were not easy to come by. The establishments that provided food often directed players to go to the back door of the restaurant or store to collect their food because the tables were only for white costumers. In these instances the food was not fresh and could be a day or more old.

While staying in a home was a treat, there were difficulties associated with it. Homes could only accommodate a player or two and as a result players would be spread out across the town. This meant that when it was time to go play a game, or move to the next town, time was spent collecting players.

In the South laws not only impacted where African-Americans could sleep and eat, they also dictated when they could be out on the streets.

Stanley Glenn shared a time when, while playing for the Philadelphia Stars, the team bus was stopped by a policeman in Clarksdale, Mississippi. "We got to the city limits and a policeman stopped the bus. He said this game will be over by 10 o'clock because we don't allow black men and white women on the street past 10 o'clock at night." Sure enough the game ended and the team was on the road and heading out of town prior to the imposed curfew.

Activity

- Why do you think white teams wanted to play Negro League teams?

- Do you feel that Negro League teams playing American and National League all-star teams had an impact on fans perceptions of African-American players? Why or why not?

Barnstorming

Barnstorming was often a challenge to the creation and ability to sustain organized Negro Leagues that asked affiliated teams to adhere to a set schedule. Teams would barnstorm not just prior to and after the organized league season but also during the season. This meant that teams would often skip scheduled league games in favor of what was perceived as a better payday from a barnstorming game or tour.

Activity

- How did playing year round benefit the Negro League player?

- Why did Negro League players enjoy playing in Latin American countries? What benefits did they receive from the experience?

- Why were in-house hotel teams were attractive to hotel owners? Do you think that this concept could occur today? Why or why not?

Activity

- Negro League teams travelled primarily by bus. What do you think the benefits of bus travel would be? What were the negatives?

- Today a Major League Baseball season is 162 games. How do you think the Negro League players were able to sustain such a high level of play despite the intense schedule?

Activity

- Describe the conditions that players had to endure when looking for a place to sleep or eat.

- What were ways that the African-American community reached out and helped visiting players?

- Meal money was often provided to players. In what ways was this beneficial to players?