Precisely 24 hours before the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s 80th induction ceremony, sportswriters and photojournalists from all over the western hemisphere gathered inside the Clark Sports Center in Cooperstown, New York, for their first look at the Class of 2019. As Harold Baines, Edgar Martinez, Mike Mussina, Mariano Rivera and Lee Smith paraded onto the stage wearing matching Hall of Fame polo shirts, the Hall’s director of communications, Craig Muder, announced that the assembled media had two minutes to capture the photo op.

The quintet stood shoulder-to-shoulder, toothy grins frozen in place. It was a natural pose at first, especially for the ever-smiling Rivera. But as the seconds dragged on, it started to get … awkward. The room was relatively quiet, save for the sound of camera shutters clicking and photographers jostling for position. But with so many different reporters looking to document the historic moment, the five Hall of Famers had little choice but to grin and bear it. When the 120 seconds mercifully concluded and every last photog had loaded up their camera rolls with enough images to crash a server, Mussina surveyed the congregation.

“Is there anybody who didn’t get one?” he shouted, eliciting laughs.

“We can do it again.”

For 18 big league seasons, Mussina plied his craft in the gauntlet known as the American League East. Relying on brains and guile rather than brute overpowering stuff, he established himself as one of the top pitchers in the league, a dependable workhorse who could be counted on in a big spot.

But over the course of one beautifully sun-drenched weekend in a small town not altogether different from the one in which he grew up, Mussina showed a side of himself that fans might have only caught a glimpse of during his playing days. Back then he could be tough with reporters, who -- perhaps intimidated by the brainy Ivy Leaguer working on a crossword puzzle in the clubhouse -- often gravitated toward easier subjects to interview. Behind that exterior, however, was a sharp-witted, self-effacing, down-to-earth kid from rural Pennsylvania who simply loved baseball. And being in Cooperstown, surrounded by the game’s greats, accepting baseball’s highest honor, the 50-year-old, gray-goateed Mussina was more than willing to let that inner child roam free. While the majority of the 55,000 attendees -- the second-largest crowd in induction day history -- were on hand to see Rivera, there was no doubt that the happy, laid-back guy busting the Sandman’s chops and delivering one-liners all weekend was also right where he belonged.

***

Cooperstown is almost implausibly picturesque, from the shops and restaurants along its one-stoplight Main Street downtown to the immaculately well-kept homes that line its quiet streets. The village’s crown jewel (other than the Hall of Fame, of course) is the 135-room Otesaga Resort Hotel. With its eight 30-foot-tall pillars out front and stunning views of Otsego Lake from the back, this Historic Hotel of America, opened in 1909, is where baseball’s immortals stay when they return for induction weekend.

Just a few yards down the shoreline, at the southern terminus of the lake, Clinton’s Dam releases the headwaters of the Susquehanna River. And about three and a half hours south of this spot, or roughly 200 miles as the trout swims, is where Mussina’s epic baseball journey was spawned.

Montoursville, Pennsylvania, has always been home for Mussina. After retiring in 2008 with 270 wins and more than 2,800 strikeouts, he returned to his hometown situated along the West Branch Susquehanna River. This past January, Mussina was in the midst of his sixth season as the head boys’ basketball coach at his old high school when he got the “incredible and surprising” call informing him that, after steadily rising in the Hall of Fame voting since receiving 20.3% in his first year of eligibility (2014), he had surpassed the 75% needed for enshrinement.

Next door to the home of the Little League World Series in Williamsport, Montoursville was an ideal place for Mussina and his brother, Mark, to spend long summer days riding bikes and playing Wiffle ball. “The Little League years were great; just playing ball, no stress,” Mussina recalled during his Hall of Fame induction speech. “It was all about pizza and Sno-cones, the packs of baseball cards with that stale piece of gum inside.”

In the late 1970s, when Mussina was about 10 years old, his parents took him to his first Major League game, driving three and a half hours east to the Big Apple. Sitting in the mezzanine behind the right-field foul pole at Yankee Stadium, Mike and his brother decided to venture upstairs and take in the view from way up high.

“Two kids from small-town America to the back row of the right-field upper deck at Yankee Stadium — with no adult supervision,” he said. “The players look awfully small from way up there. That was my first taste of the Major Leagues.”

But for all the successes that Mussina would go on to experience after that moment, he never forgot where he came from. “Every time I leave Williamsport,” Commissioner Rob Manfred said during a party in Rivera and Mussina’s honor hosted by the Yankees at Cooperstown’s Brewery Ommegang the night before the induction, “one of the things that strikes me is the people in that part of Pennsylvania talking about how much Mike Mussina does for Little League, but more importantly, how much he does for youth sports in general in that part of the country. Both [Mussina and Rivera] have been unbelievable about giving back to our game.”

***

The decision to go with no logo on the cap of his bronze plaque wasn’t a hard one. “I kind of made it in about three or four minutes,” Mussina said. Those countless hours spent playing Wiffle ball led to a high school pitching career that netted a state championship for Montoursville and caught the attention of the Baltimore Orioles, who drafted Mussina in the 11th round in 1987. The 6-foot-2 right-hander didn’t throw much other than his fastball, though, so he decided to further hone his craft at Stanford, winning an NCAA championship as a freshman. Baltimore came calling again in 1990, selecting a more advanced Mussina with the 20th overall pick. (Along with Baines and the late Roy Halladay, Mussina makes 2019 the first Hall of Fame class to include three first-rounders.)

After just 28 Minor League starts, Mussina got the call to the bigs, losing, 1-0, at Comiskey Park in his Aug. 4, 1991, debut (thanks to a home run by now-fellow Hall of Famer Frank Thomas). The following season marked the opening of Camden Yards near Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, just down the coast from where the Susquehanna empties into the Chesapeake Bay in Havre de Grace. Pitching in front of a packed house of orange-and-black-clad fans every night, the 23-year-old Mussina was dominant in his first full big league season, going 18-5 for a Major League–best .783 winning percentage and making his first of five American League All-Star teams.

Back-to-back 19-win seasons in 1995 and ’96 led to his first taste of the postseason, bouncing Cleveland in the 1996 ALDS before falling to the Yankees in the ALCS. Mussina was lights-out the following October, defeating Randy Johnson and the Mariners twice in the ALDS then twirling two gems against Cleveland in a six-game ALCS loss.

Fans in Baltimore weren’t the only ones impressed by Mussina’s performances when it mattered most. “I put so much more weight on pitching the important games and how many times they pitch in do-or-die situations,” said Hall of Fame manager Joe Torre. “And to me, Moose is as good as any of them.”

Sanitation workers in Lower Manhattan were still cleaning up after the Yankees’ third straight World Series victory parade when Torre phoned Mussina, a free agent after the 2000 season, to let him know that he and general manager Brian Cashman wanted him to be part of their future plans. Mussina was impressed by the overture, and on Nov. 30, 2000, he signed on to make Yankee Stadium -- the same place where he had witnessed his first Major League game -- his new home.

“For the longest time while I was in Baltimore, I told myself that I would never play in New York,” Mussina said. “I’m a small-town guy, and that place was just too much for me. Well, obviously I changed my mind, mostly because of Joe Torre.”

From the get-go, it was a perfect fit. Mussina won 17 games in his first season in New York, finishing in the top five among AL Cy Young Award vote-getters for the sixth time in his career. His first postseason start for the Yankees was as pressure-packed as they come: Amid the emotional turmoil of 9/11, the Yankees fell behind Oakland, 2 games to none, in the 2001 ALDS, then handed the ball to Mussina for Game 3 on the road. Barry Zito tossed eight innings of one-run ball for the A’s, but thanks to Mussina’s seven strong innings, Rivera’s two scoreless frames and a heads-up “flip play” by Derek Jeter, the Yankees claimed a 1-0 victory and took back the momentum in the series.

“Moose was a different kind of pitcher,” said former teammate Bernie Williams, who performed the national anthem and “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” on electric guitar at the July 21 induction. “He had pinpoint accuracy. His best pitch, I think, was his knuckle-curve, and everything kind of went off of that knuckle curve. It was a 12-to-6, hard, biting pitch. If you kind of waited for that, then he had a 90-plus mile per hour fastball that he could spot in any location. He was really, really difficult to face, and added to that was the fact that he was very smart. He knew how to read body language. He knew how to attack hitters’ weaknesses. He was a tough competitor. He would give you everything he had. He would never give up.”

Mussina would help the Yankees to their 38th pennant, teaming with Rivera to win Game 2 of the 2001 ALCS at Seattle, and reach the World Series for the first time in his career. He struck out 10 Diamondbacks in Game 5 -- the third of three one-run Yankees victories in three nights during the 2001 Fall Classic.

But it was his performance two years later -- in relief, ironically -- that remains cemented in pinstriped lore. Rivera, the Hall of Fame’s first unanimous inductee, calls it the most memorable game of his career. Peter Gammons, the Hall of Fame baseball writer, said it was “one of the most consequential games in baseball history.”

Game 7. Yankees–Red Sox. The winner goes to the World Series. The loser goes home. Roger Clemens and Pedro Martínez started it. Aaron Boone ended it. But in the third inning, with Clemens exiting after he surrendered four runs and left runners on the corners with nobody out, it was Mussina who came to the rescue.

Pitching coach Mel Stottlemyre had told Torre before the game that Mussina, who started Game 4 in Fenway Park three days earlier, would be available out of the bullpen, but only to start a clean inning. “I said, ‘OK, that’s fine.’ But when we got in trouble all of a sudden, I say to Mel, ‘Get Moose up,’” Torre said. “They have a chance to blow the game open at this point in time, so I went out and made the pitching change. Moose has absolutely no expression on his face. He comes in business-like, takes the ball from me, proceeds to get out of the inning.”

A strikeout, a double-play ball, two more scoreless innings, and two hours later, Mussina was heading back to the World Series with the Yankees.

“Both organizations were tremendously involved in this, and I just don’t feel right picking one over the other,” Mussina explained of his plaque. “The decision to go in without one logo versus the other logo, it’s the only decision that I can make that I feel good about.”

***

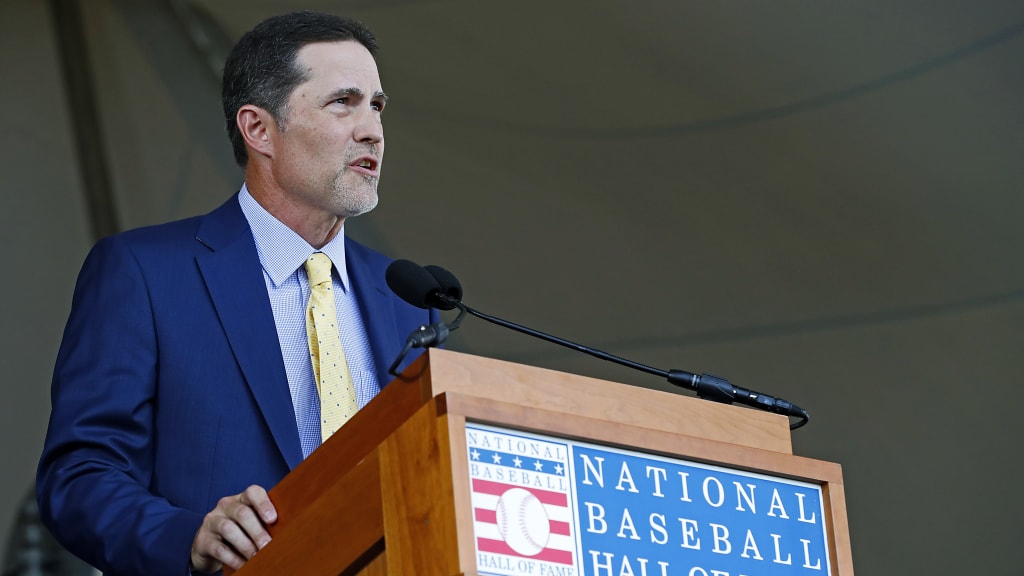

It was evident, from the sea of teal Mariners jerseys and the abundance of Panamanian flags in the crowd, that fans had traveled from far and wide to show their love for this year’s Hall of Fame inductees. It was also evident, from the bright orange O’s caps to the dark red No. 25 Stanford jersey and Montoursville athletics gear in the crowd, that Mussina’s supporters were thrilled to be there for their guy. They felt a shared pride when he spoke glowingly about his hometown, and laughed out loud when his opening remarks included the lines, “I’m standing up here with the best who ever played the game -- some are my former teammates, some are former opponents, some I grew up watching on television. So, the obvious questions are: What am I doing up here, and how in the world did this happen?”

It happened naturally. There was no fall ball or summer travel teams for young Mike Mussina, just a love of the game forged in the backyard that led to an incredible 18-year career without an arm surgery. He was fortunate to come from a great family in a great community and eventually marry a great woman, Jana, who did the lion’s share of raising their three children, Kyra, Brycen and Peyton, so that Mussina could wrap up his career on his own terms -- which he did, defeating Boston at Fenway Park on Sept. 28, 2008, to reach 20 wins for the first time in his final game.

In reflecting on the journey that led him from the banks of the Susquehanna to its source, and thanking all the “pieces of a giant puzzle” that helped him reach baseball’s spiritual home, he concluded that, for him, this was the way it had to be -- and he wouldn’t change a thing.

“I was never fortunate enough to win a Cy Young Award or be a World Series champion,” Mussina said. “I didn’t win 300 games or strike out 3,000 batters. While my opportunities for those achievements are in the past, today I get to become a member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Maybe I was saving up from all of those ‘almost’ achievements for one last push. This time, I made it. Thank you to baseball for an awesome ride. To all the fans for supporting this great game, and to all of you for being here with me today, thank you.”