SARASOTA, Fla. -- The grizzly bear ambling across Brandon Bailey’s left arm is drawn in ink, rooted in tradition and surrounded by more symbols on all sides. Above it, a Native American warrior watches, war paint climbing down from Bailey’s shoulder. To the right, a biceps-sized bison stirs. Below, a 28-sided triangle chain stretches like a bracelet east to west, touching generations past and future.

If the grizzly somehow managed to find its way across the wilderness of Bailey’s upper torso and onto his other arm, it’d collide with depictions of two more staples of native culture. The tattoo of the woman, wearing the bear headdress and painted mask, symbolizes gender equality and Bailey’s sister, Bri. The wolf howling below her seems to be calling to everything else, caught in an eternal search for connection: between generations, between cultures, between humanity and the natural world.

Together, they form a mural draped across the upper body of Bailey, one of the two Rule 5 Draft right-handers in Orioles camp. Every time he kicks and delivers, the whole tapestry rises and falls in tandem, like the moon and sun, so that both carnivores peek out from Bailey’s jersey sleeve while he throws, as if it were a horizon. That morphs each pitch into a tribute, designed in intricate detail to honor his family’s Chickasaw ancestry.

“It’s something we are very, very proud of,” said Bailey, who at one-eighth Chickasaw is enrolled as a citizen of the tribe. “For me, it’s trying to keep my family heritage alive, but it’s also trying to give back to the people, who, over the course of time, were told their background was wrong.”

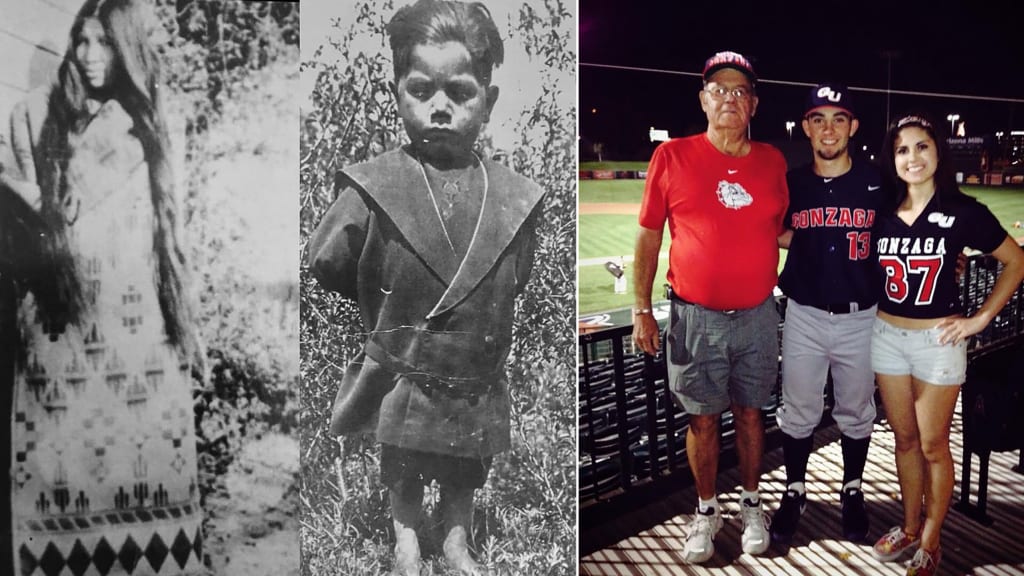

Known as the “Spartans of the Lower Mississippi Valley” by some historians, “The Unconquerable” in tribal lore, and later as one of the “Five Civilized Tribes” by the U.S. government, the indigenous Chickasaw first encountered Europeans while living in northern Mississippi, Alabama and Tennessee. Bailey’s great-great-great-grandmother, Matahoya, walked the “Trail of Tears,” according to the family’s oral history. Her son, George, Bailey’s great-grandfather, was full-blooded Chickasaw, born, raised and Americanized in boarding schools on the tribe’s Oklahoma reservation. A World War II army veteran, George married outside the nation and moved the family to Colorado after his military service.

“He did not want his children to grow up in the same scene as he did,” Bailey said. “After that, he never was the same, and he wanted to get away from that part of his life.”

From there, the Baileys' native lineage dwindled through the generations. George’s son, Keith, is Bailey’s grandfather. His father is Brad. Brandon and Bri, who grew up in the Denver metropolitan area, are of mostly white and Spanish descent, and Bailey knows it’s possible his future children will feature even smaller quantum levels of Chickasaw blood. (To be eligible for enrollment into the tribe, one must only be able to establish that they are a lineal descendant of an original enrollee on the Dawes Rolls, according to a Nation official).

“When my grandfather [George] left Oklahoma, he was 18 years old, and he said he would never go back,” Brad Bailey said. “It was important for me because the traditions were kind of lost between my dad and me. ... Now, it’s coming full circle.”

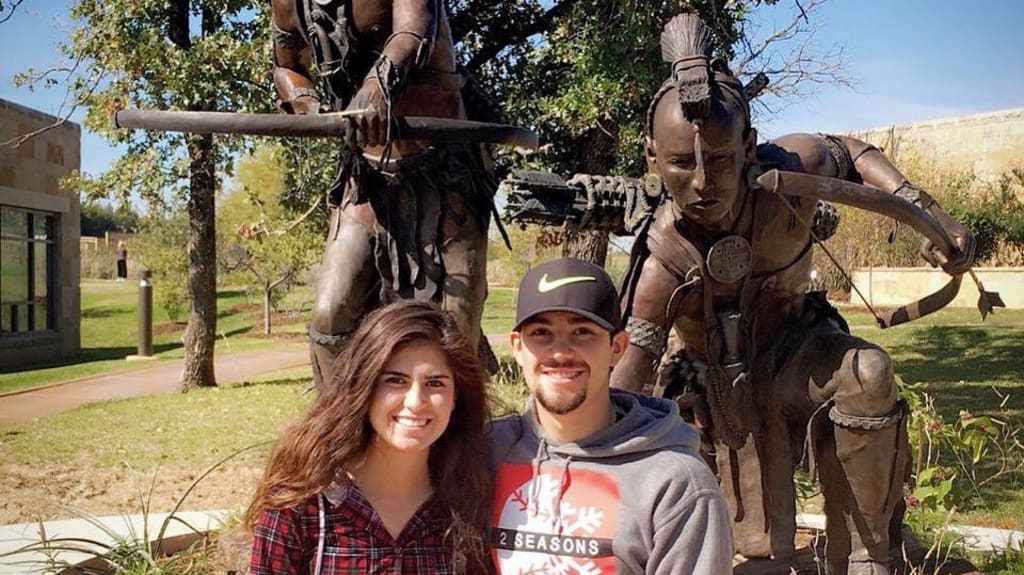

Brad began looking to reconnect with his native roots in the early ’90s, soon after Brandon was born. Though he raised his family hundreds of miles removed from Chickasaw Nation’s headquarters of Ada, Okla., Brad Bailey purposefully -- and routinely -- exposed Brandon and Bri to native culture. The family attended community outreach programs put on by the Nation and other tribes, traveling across the region for art festivals, family reunions and other events. They subscribed to the Chickasaw Times, a monthly newspaper published out of Ada. Bri originally attended Gonzaga but transferred to the University of Oklahoma, in part to be closer to her native roots.

Now 25, Brandon Bailey minored in Native American studies at Gonzaga, plans to learn the Chickasaw’s historic language, and speaks passionately about the dangers of forced cultural assimilation. If he reaches the Majors, he’d join current Minor League manager Wyatt Toregas, journeyman reliever Dallas Beeler and 1930s righty Euel Moore as the only Chickasaw natives to do so.

(In an amazing wrinkle, the Baileys learned during the course of the reporting of this story they may be related to Moore; George Bailey, Brandon’s great-grandfather, was actually born George Moore but legally took his step-father’s name.)

Brandon Bailey said he hopes to use his baseball platform to become an advocate not only for native issues, but also to help other young native people struggling with the complexity of their identities. Native people face disproportionately higher poverty, alcoholism (510 percent), suicide (62 percent) and high school dropout rates compared to national averages, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

“I don’t even think I could put into words how much that would mean to us,” Brad Bailey said. “I think it gives him a sense of pride in who he is. Every time he goes on the mound, he wants to represent the Chickasaw.”

What would his message be?

“I didn’t grow up on the reservation with you, but I know you exist, and I want to help any way I can,” Brandon Bailey said.

*****

Born weighing 9 pounds and with a thick, black mane of hair, Brandon was given both American and native names at birth. The latter, “Nita’ Iskanno’si,” was bestowed by Keith. Years later, it would inspire the grizzly tattoo.

Translation: “Little Bear.”

“Well, he looked like one,” Keith said, chuckling, in a phone interview. “You could see he had this energy, this determination and this awareness, even then.”

Said Brad: “It still suits him so perfectly.”

The righty’s tenacity remains an integral part of his personality, and his height will always be a part of his story. Despite being listed at 5-foot-10 (realistically standing shorter than that), Bailey has worked and willed his way on to the Major League periphery despite his non-traditional build. After being told in high school he’d be too small to pitch Division I, Bailey hit 95 mph as a junior, overcame Tommy John surgery and still had more than half a dozen scholarship offers from which to choose.

He blossomed into an all-conference starter in Spokane ... and before the Draft, was rejected on the spot by one Rockies scout who used a tape measure to literally measure him by hand. This week in the Orioles dugout, manager Brandon Hyde was comparing Bailey to undersized MLB mainstay -- and All-Star -- Marcus Stroman.

“He’s not the usual big stature pitcher, but there are a lot of guys that are a little shorter that are successful in the big leagues,” Hyde said. “We’re excited about the pitch mix that he has. He’s got five really good weapons.”

The Oakland Athletics ultimately made him a sixth-round pick in 2016, then traded Bailey to the Astros for Ramón Laureano the following November. He spent all of 2019 at Houston’s Double-A affiliate in Corpus Christi before the rebuilding Orioles, starved for rotation candidates and eager to add young talent, scooped him up with the second pick in December’s Rule 5 Draft. Bailey was doing at the time what he’s does every winter -- studying biomechanics and pitch design at Seattle’s famed Driveline pitching lab.

Driveline exploded in popularity after the publication of Jeff Passan’s 2016 book, “The Arm.” Bailey has been going since 2014, diving head-first into the lab’s tech-based approach to pitching development. It’s helped turn Bailey into an unconventional strikeout pitcher, with a five-pitch mix Hyde described recently as “a bag of tricks.”

Bailey works off a low-90s fastball that plays up due to his high spin rate, using it in tandem with a changeup that scouts consider his best offspeed weapon. He also features a spike curve and slider that he can morph into a cutter at times, and Bailey draws rave reviews for his makeup and competitiveness.

Though many still believe his future is ultimately in the bullpen, Bailey is one of seven pitchers being stretched out for consideration for three open spots in the Orioles' rotation. He arrived in Sarasota seemingly on more stable ground than most Rule 5 picks typically do, given the Orioles’ place on the competitive spectrum and all their uncertainty on the pitching side. Baltimore could easily audition Bailey in a variety of roles to keep him on the active roster all season, even if he doesn’t make the rotation out of camp.

*****

The hyper-inquisitive Bailey has a photographic memory, is fascinated with astrology, and stuffs philosophy books behind cleats in his locker. He could recite full MLB rosters and mimic batting stances by the age of 3. He has written a pitching blog, subscribes to the famed self-help teachings of “The Secret,” can speak fluently about the principles of growth mindset, and dove into data before it became mainstream. It is an eclectic mix of interests not often found within the walls of a Major League clubhouse.

“I think high school was a good time for him but also a tough time for him,” Brad said. “It wasn’t cool to be a jock and to be smart.”

By college, it was. Bailey made the president's list at Gonzaga, earning All-Academic conference and region honors during his junior year. He nearly bypassed pro ball altogether after receiving Nike’s N7 internship that May, weeks prior to the Draft. Bailey beat out thousands of applicants for the chance to work for Nike’s N7 Fund, which raises money to promote health and disease prevention programs among native tribes. He says he would’ve taken the position had the A’s not matched his $300,000 asking price that June, and still hopes to work for Nike should this baseball thing fall through.

“It was one of the more difficult things I’d ever had to help him through, since there were a lot of right answers, and which the most right was, was hard to determine,” Brad Bailey said. “All of us were torn. But we also knew Brandon had dreamed of playing professional baseball since he was 3.”

Contract in hand, Bailey chose to honor the N7 opportunity permanently -- with a tattoo of its logo within his native body mural. He hopes it’ll soon help “bring social awareness to all the issues going on in native country, to give all the young kids motivation to be active, to move, to live healthy lifestyle through sport,” he said. Other goals include helping part-native people (“I know I look more white than I do native,” Bailey says) embrace their ancestries and speak out against injustices in ways he feels the country’s social and political climates, for generations, have discouraged.

“It’s really unfortunate that in our own country, not many people talk about [what happened to Native Americans],” Bailey said. “I think it’s something people are ashamed about actually happened, and don’t want to think about it and don’t want to know the facts about what took place at the expense of a lot of people.”

Before his great-grandfather George died, Brad and Brandon heard him speak in Chickasaw rarely.

“Do you remember the language?” Keith asked his father.

“I do,” George replied. “But when you get beat for speaking it, it makes you want to forget.”

Bailey plans to have children one day. He wants things to be different.

“There isn’t going to be that dominant connection, but I think it’s good for them to know their grandfather and great-grandfather were native,” Brandon said. “I think it’s important for them to know what happened to the people who came before them. It’s history that needs to be told.”