It wasn’t that long ago, a little more than two years now, but the new third-base coach for the New York Yankees remembers the day fondly.

It was Jan. 22, 2020, and Luis Rojas had ascended to the top of the New York Mets organization. A veteran coach with years of Minor League Baseball experience, Rojas had the backing of key players as well as the Mets’ front office. It was a proud moment for the newly minted manager, one that had Rojas’ cellphone buzzing early and often that day, but the first call left a lasting impression.

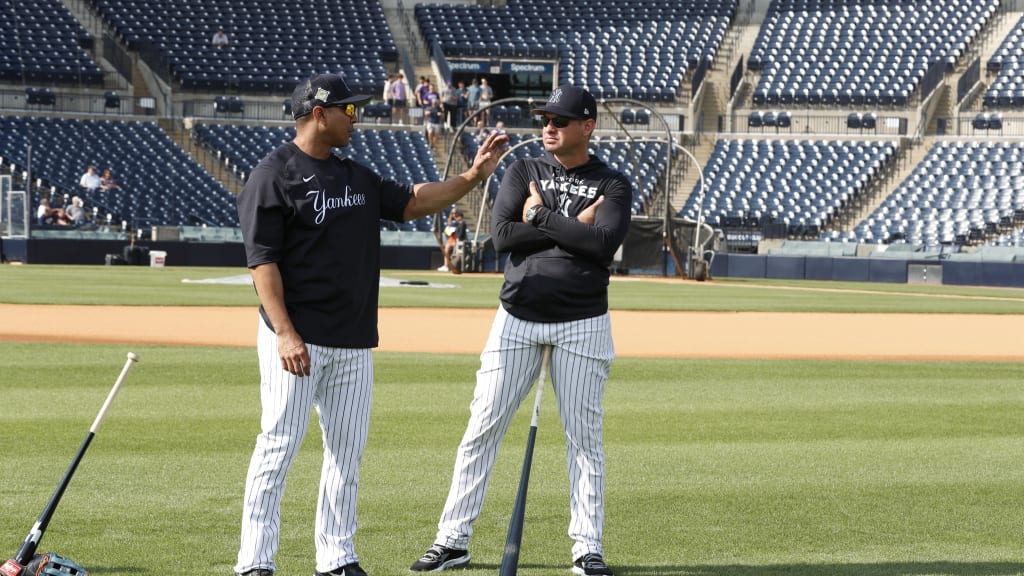

“Aaron Boone was the first person who called me when I got the Mets job,” Rojas says. “I thought that was pretty neat. We established a good connection.”

What ostensibly was a congratulatory, welcome-to-the-neighborhood call from the Yankees manager turned into much more. A bond was formed, and it was a subsequent call from Boone almost two years later, shortly after Rojas was dismissed by the Mets following the 2021 campaign, that cemented their kinship and a friendship formed by the familial ties of growing up among baseball royalty.

“I was in the Dominican Republic when Aaron reached out, and we talked about me and the third-base [coaching] job,” Rojas says. “There were just a lot of things, on a personal level, that were very interesting to me. Aaron is a great manager and a great leader.”

It’s likely that one of the things they discussed was their families, and the legacies that both men carry.

Luis Rojas is the son of the legendary Felipe Alou, a former Yankee himself who became only the second native of the Dominican Republic to play Major League Baseball and the first to make the bigs directly out of the Caribbean nation when he debuted with the San Francisco Giants in 1958. Alou also became the first Dominican native to manage in the Majors when he was named the field boss of the Montreal Expos in 1992. He had the Expos cruising toward a National League East title in 1994 when the Major League Baseball season was canceled in August of that year when the players went on strike.

The name disparity between father and son happened when a baseball official unwittingly stitched “Alou,” his mother’s maiden name, on the back of Felipe’s first jersey. But the Alou name, of course, became legendary. Felipe’s brothers -- Luis Rojas’ uncles, Jesús and Matty -- also made the Major Leagues, as did Rojas’ half-brother, Moises, a six-time All-Star in his 17-year career.

And Rojas had chapter and verse on the family history when he entered the profession.

“The legacy is tremendous and, of course, you want to perform up to it. Motivation and inspiration is the main thing. You want to impact people’s lives in the game and around the game,” the new Yankees coach says.

But certainly, there were moments of doubt.

“Yeah, absolutely, there was some anxiousness, too,” Rojas says. “I had it in my head in terms of what I was going against, to follow the family footsteps and the legacy. But for me it’s a win-win. I call it a transition of maturity. It became a case of, how could I absorb some of the things accomplished by my family?”

Boone knows the feeling well. In many respects, he and Rojas are kindred spirits.

The Boones are as well known a baseball family as can be. Aaron’s grandfather, Ray, was an infielder who was an American League All-Star in 1954 and ’56. Ray led the AL with 116 RBIs in 1955 for the Detroit Tigers, the second of his six teams during a 13-year career.

Aaron’s father, of course, is Bob Boone, a four-time All-Star with the Philadelphia Phillies and California Angels who helped lead Philly to the 1980 World Series championship. Like Aaron, Bob Boone also managed, skippering the Kansas City Royals and Cincinnati Reds.

Bret Boone, Aaron’s brother, was a standout player on five teams whose best years came during his time with the Seattle Mariners. Bret slugged 252 home runs and knocked in 1,021 runs during a 14-year career that saw him win four Gold Glove Awards and earn three All-Star selections. When he broke in with Seattle in 1992, Bret made baseball history as the first third-generation player to make the Majors. In 2016, he released an autobiography, aptly titled Home Game: Big-League Stories from My Life in Baseball’s First Family.

Aaron’s nephew, Bret’s son Jake, just completed his first pro season in 2021 in the Washington Nationals organization and could be the first fourth-generation player in the Majors someday.

And there’s no need to rehash Aaron Boone’s career with Yankees fans. He solidified his place in Yankees lore with his dramatic Game 7, 11th-inning, game-winning home run to beat the Boston Red Sox in the 2003 American League Championship Series. He was named manager in December 2017.

Like Rojas, Boone calls the family legacy “overwhelmingly positive for me.”

“I grew up with two parents who were super supportive and, obviously, having a dad who played in the big leagues from when I was born to my senior year of high school was pretty influential,” Boone says. “My brothers and I had lockers in the clubhouse. We grew up in the clubhouse. Being in that environment, it was a childhood dream. From a baseball standpoint, it helped me as a player and now as a manager.”

Boone came late to managing, having spent 12 seasons as a player with six teams and eight as an analyst on ESPN baseball broadcasts.

But Rojas came around to the idea of coaching fairly early on.

Born in 1981, Rojas wasn’t even a teenager yet when he began roaming the outfield during batting practice and running the bases while Felipe Alou managed the Expos. As a teenager, Rojas signed with the Baltimore Orioles and was given a $300,000 bonus. But shoulder issues hampered his playing career, and after six years, he accepted that his dream of playing third base in the Majors was over.

“I was in denial about quitting baseball, and my father was one of the people who helped me make the transition,” Rojas says. “We talk a lot. I have, and always will, consult with him. He wasn’t sure about the remainder of my career continuing as a player. I mean, I played for three teams in six years in the Minors. He told me if you start your coaching career now, you’re going to start early and you’re going to make an impact.”

Rojas pauses and lets out a small chuckle.

“In retrospect,” he says, “my father made it sound really simple.”

In 2006, he was hired by the Mets and spent his first full season in the organization coaching in the 2007 Dominican Summer League. He moved up the ladder, leading the Savannah Sand Gnats to a championship in 2013 and earning South Atlantic League Manager of the Year honors the following season. His rise culminated with Rojas reaching the Majors as Mets quality control coach in 2019 and, ultimately, field boss in 2020.

When he was hired to lead the Mets, Rojas spoke reverently about his father, and in several interviews referenced having gone through the “university of life.” Asked to reflect on what he meant, Rojas is heartfelt.

“The university of life was about how much orientation my dad gave to all of us,” Rojas says. “He talked about his experiences as a Latino baseball player, someone who left the country not knowing any English, how he overcame some adversity and made it to the big leagues, and more importantly how he blended into society as a man. We talk life and baseball. I listen more than I talk.”

That sort of outlook and those kinds of communication skills figure to be a big part of the Boone-Rojas dynamic, the groundwork of which was already being laid long before Rojas put on the pinstripes.

“We had a really good first conversation, and he presented himself simply as, ‘I’m here if you need me.’ We actually talked a lot during the pandemic,” Rojas says. “It immediately tells you the kind of person you’re dealing with. He’s pure class. He’s a pure baseball man. You take that into consideration. A real good leader.”

“When he first got named as the Mets manager, I just wanted to reach out and welcome him,” Boone says. “There’s still that manager fraternity, and I wanted him to know he had somebody right here in New York to talk with and bounce stuff off. I just wanted to say ‘Hi’ and introduce myself.”

Two years later, Boone did more than that.

When Boone’s contract was extended following the 2021 season, the Yankees also went through a number of coaching changes. Rojas had just been let go by the Mets and, well, it wasn’t hard to connect the dots.

Rojas says Boone was one of the first, if not the first, to reach out about a potential job.

“We talked about the job, our philosophies, the organization, and it gave me a real sense of the Yankees’ culture,” Rojas says. “Throughout the interview process, it became appealing to me to work with, and for, a guy like Aaron. I felt blessed when he called me, and they had an offer for me.”

Boone says that their conversation from two years ago and their subsequent interactions throughout Rojas’ stint as Mets manager might have been limited but were insightful. It was something he and the Yankees used as their foundation, and their admiration of Rojas only grew during the interview process.

“He was always somebody that, certainly, I gained respect for and enjoyed my interactions with, and somebody I enjoyed talking with,” Boone says. “But once we started to do our homework on the different [coaching] positions we had, we felt like Luis was a guy who had gained a lot of respect, not just in our eyes, but in the entire game. People that we value were talking about what he brings to the table. This is a guy with a lot of experience. When we got a chance to speak with him, he really impressed us all. He was knowledgeable, likable and his experience shined through. We feel like we brought in a very capable person.”

Now Rojas takes over what is arguably the most important on-field, in-the-moment coaching position in baseball. He is already looking back at past notes he made with the Mets during Interleague competition against AL teams.

“Oh, we could talk for hours about the art of coaching third base,” Rojas says. “There’s so much to it. Let’s just say it’s a very exciting position in the game. You need to know the opposition. You need to know tendencies, strengths, weaknesses. You need to know that Tampa is very athletic in the outfield, for instance, and that Boston has good arms. You need to study those guys. You need to do your homework from series to series, from day to day.”

He will do more than just coach third base, though. Rojas will also serve as the team’s outfield coach, and Boone indicated he will lean on Rojas quite a bit and take advantage of Rojas’ managerial experience. The new guy will also have an impact on the Yanks’ running game as they try to manufacture more runs this season.

But, mainly, Rojas will be responsible for making split-second decisions when the Yankees are batting.

“For third base, you like to have a guy who is experienced,” Boone says. “He has a number of years coaching third base, and to have those reps and those physical mechanics is important. It’s a pressure-packed position, especially in New York. You have to have a lot of confidence and broad shoulders. You have to have a short memory.”

Rojas is fully aware.

“It’s one thing to be a thinker and be contemplative and to run through scenarios,” he says. “But when it’s bang-bang and you make your decision, it’s a whole different animal.”