Steve Sax has always been moving.

From his childhood -- when he would “run everywhere” -- to his days as a Major League second baseman who stole 444 bases (and ran, not jogged, to first base when he was walked), was selected to five All-Star teams and won two World Series championships with the Dodgers, he’s always known one speed: fast.

The speed was coupled with passion. Sax was passionate about baseball beginning in his youth, so much so that he attained heights in the game that few reach.

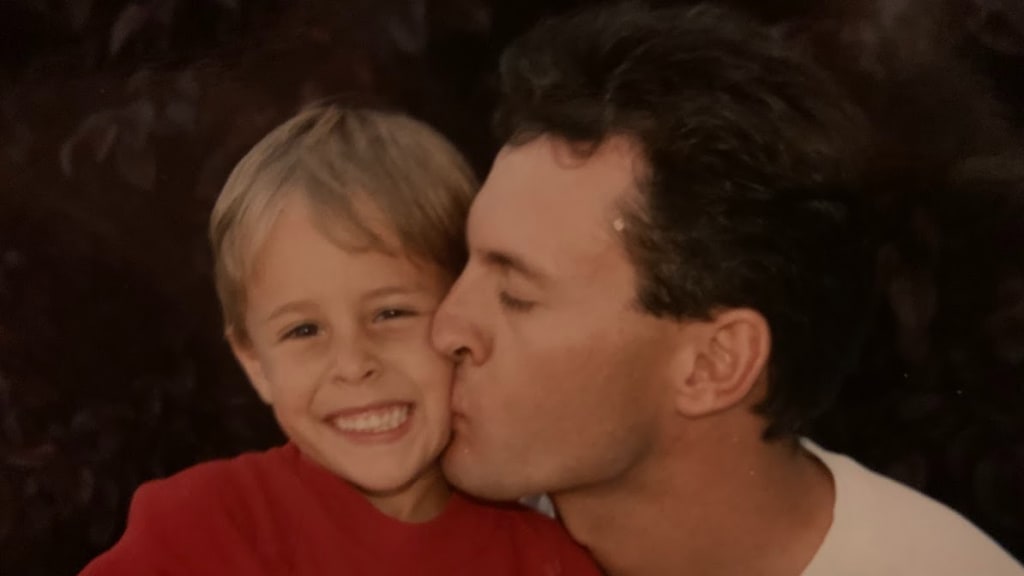

Then, he had two children. And the passion he had for his kids was beyond anything he could have imagined.

“It goes without saying: I was extremely close to my son, as I am with my daughter,” Sax said. “I’m very close to my kids.”

When Steve’s son, John, died in a military aircraft accident in 2022, he was shattered. But he has channeled his devastation into what he knows how to do so well: move.

“It’s one of those things where it never goes away or gets any better,” Steve said of the pain over losing a child. “You just try to move forward. That’s all you can do.”

Through the Steve Sax Family Foundation, Steve has raised money toward helping young people with dreams similar to those of his son achieve those dreams.

And in his latest project to that end, he has teamed with renowned sports artist Opie Otterstad to blend his passion for baseball with his son’s passion for flying, all to honor John and continue producing hope from tragedy.

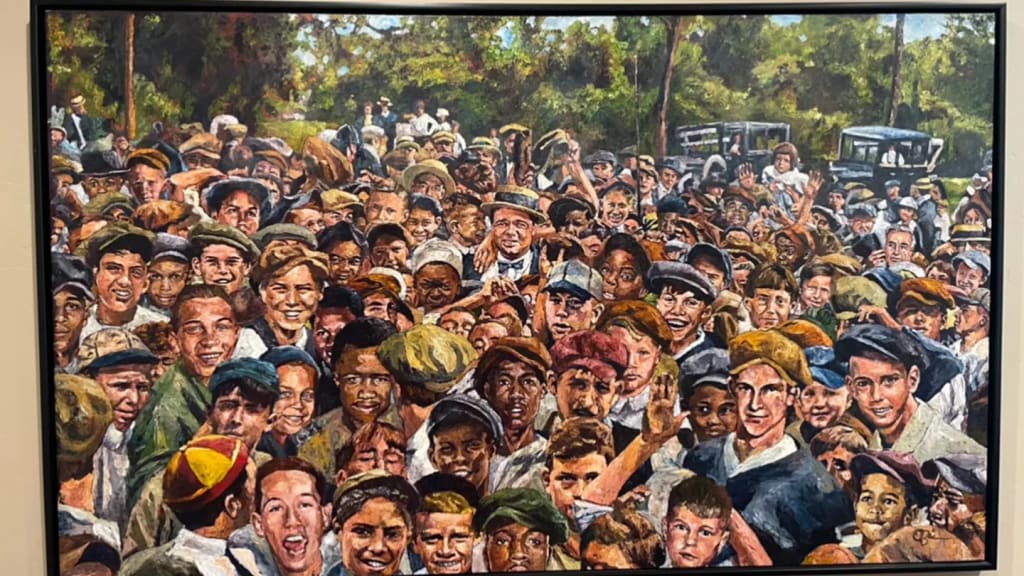

Babe and the Kids

When he first laid eyes on it, he knew he had to have it.

“I saw this painting after getting an invitation to an exhibit in New York City during All-Star week in 2008,” Sax said. “This thing was under a light and it was showcased.

“As soon as I walked in, I said, ‘I’m buying that painting.’”

That painting is called “Babe and the Kids,” and Steve has digitized it into an NFT and placed it on the Ethereum blockchain, minting 200 limited edition copies for sale, with a portion of the proceeds going directly to helping young people who have dreams of taking flight.

“Babe and the Kids” was a special project of Otterstad’s, one that took more than eight years from concept to finished product due to the depth of research that was needed to complete it.

It features a familiar sight for many baseball fans since it is based on an iconic photograph of Babe Ruth during a barnstorming stop, surrounded by a throng of adoring children. But Otterstad decided to give it his own twist as a nod to all who followed in Ruth’s footsteps in the decades after he changed the game forever.

“In our library, we have about 1,200 books on baseball,” Otterstad said. “And I would come across that photo in many of them. And I would look at all the kids’ faces and I would wonder if any of them grew up to become like a mayor or state representative or somebody of note.

“And then I thought, ‘Well, what if they all grew up to be someone of note?’”

Otterstad decided to paint “Babe and the Kids” with the kids being future Hall of Famers.

For the next eight years, Otterstad gathered photographs of Hall of Famers from when they were children, utilizing biographies, visiting county records offices and calling players he knew. He even made two trips to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

Otterstad was able to get most of what he was looking for, but there were a couple of players for whom no such photo could be found.

So he improvised.

“I called Juan Marichal because I couldn’t find a photo of him as a kid,” Opperstad said. “And he said that was because none exist. And the other one I couldn’t find was for Roy Campanella.

“So in the painting, Campanella is actually his son, who is a dead ringer for Roy. And for Juan Marichal, I chose an image of his daughter, who is also a dead ringer for what he would look like as a kid.”

Carbon copies

There’s a connection between Steve and his son that is embedded within the “Babe and the Kids” painting, one that Steve couldn’t have known about when he was instantly captivated by it.

If Steve had been one of the subjects of Otterstad’s painting, and Otterstad needed an image of him as a child though none was available, a photo of John would be virtually indistinguishable.

“When my mom saw my son for the first time, it took her breath away,” Steve said. “She said, ‘That’s Steven.’ I used to tell John all the time -- I said, ‘I feel sorry for you, son … when you grow up, you’re going to look exactly like your dad.’

“We were like carbon copies.”

John Sax was the spitting image of his father. And he was like Steve in so many other ways. One of those was the passion with which he chased his dreams.

For Steve, it was baseball. For John, it was flight.

It all began when as a boy, John was taken up in a World War II-era biplane by a family friend.

“He absolutely loved it,” Steve said. “He just fell in love with flight.”

The dreams of father and son crossed paths one day while John was an outfielder in Little League.

There was a fly ball that was headed toward John, and as he looked up to track it, something else caught his eye and the baseball fell to the ground behind him while John continued to stare at the other object.

“People are yelling, ‘Johnny, get the ball! Get the ball!’” Steve remembers. “He just kind of gathered himself, got the ball and threw it in. After the inning was over and they started to run in, I said, ‘Johnny, what’s going on out there?’

“He said, ‘Oh, I saw the fly ball. But did you see that C-130 transport plane that flew over?! That thing costs $8 million just for the engines! It takes seven people to fly that!’”

As with any dream, there are obstacles. For Steve, he had them as he chased his dream to reach the big leagues. He had more when he got there -- in 1983, during his third Major League season and after winning the 1982 National League Rookie of the Year Award, he suddenly couldn’t make routine throws to first base. His case of the “yips” led to 30 errors that season.

But Steve, with the help of his father, overcame that, earning three more All-Star selections and helping the Dodgers win it all in 1988.

For John, too, there were some major roadblocks he had to break through to reach his goal. And he did.

“My son didn’t have an easy trek to becoming a marine,” Steve said. “When he died, he was a captain in the Marine Corps. He first went to the Navy and he got declined because he had broken his elbow. He had it repaired by the Dodgers’ doctor, Neal ElAttrache. So he got back in line, and then they said that now he had astigmatism in his eye. So he had to go get that fixed.

“After he got that fixed, he got a degree in aeronautical science and went through officer candidate school. When he was finally accepted into the Marine Corps, he just blew his tests out of the water -- he was in like the top 5% of the Marine Corps.”

John’s journey was tough on Steve, too. While he didn’t know the first thing about aviation, he knew flying was John’s love, and he wanted to do all he could to support that. It was hard to watch him struggle, but Steve knew it was necessary.

It was not only uneasy, but even downright scary sometimes.

“When I saw him taking his G-force test, it terrified me,” Steve said. “I thought his head was going to explode. But he was not quitting. No quit, ever. The stuff they put him through in officer candidate school, it’s no wonder so many of them quit. But he didn’t quit. It wasn’t an option.

“When you have a passion for something, it gets you through the downtimes. It gets you through the struggles. And that’s what I saw in John.”

Powerful

There is a letter, framed on a wall in his home, that Steve Sax cannot reach the end of without crying.

It was written by Lieutenant Colonel John Miller, John’s commanding officer and the man who gave John’s eulogy in front of more than a thousand marines in 2022:

“John spoke of you often and about how great his childhood was. What is most amazing to me is that he never once mentioned that you were a professional baseball player. Humility was his most impressive character trait. He loved you, Deborah, Lauren and his family dearly. … His life and legacy are a direct testament to how you raised John and for that, you should be proud.”

“It’s the most unbelievable letter I’ve ever read,” Steve said. “To this day, I can’t read it. I have to have somebody read it to me. It’s so powerful.”

John was the type of guy people gravitated to. His character was something that was instantly evident to those who had a chance to meet him.

His first job was at a Safeway grocery store on Sierra College Blvd. in Roseville, Calif. Steve told John when he was 15 that if he wanted a new car, he’d have to work for it.

“He went to Safeway at least 10 times,” Steve said. “And finally, the store manager said, ‘OK, fine, I’ll hire you!’”

On his first day, he met co-worker Cecilia Ruiz. And he instantly made an impression on her, as well as the others he worked with at Safeway as a grocery-bagger. Cecilia and two other ladies who worked there came to be known as John’s “three moms” at work.

That’s saying a lot, given that Cecilia is a Giants fan, and John was the son of a Dodgers great (though Steve himself wasn't exactly a Dodgers fan growing up, either).

“He was our son,” Cecilia said. “I remember his first day like it was yesterday. Steve was looking at John through the window outside while John was bagging groceries. It was this special moment.”

Things went from heartwarming to hilarious.

“He came to me and asked, ‘Hey Cecilia, do you know where the bags are?’ And I said, ‘John, you’re holding one.’

“We laughed for two years on that one.”

These days, people still talk about John at that Safeway, both former co-workers and customers alike.

When John went somewhere, you knew he had been there even after he had left. There was something about him that changed a room when he was in it.

Even now that he’s not with us, the impact he had on people endures.

“I still have people, when I go through the line at Safeway, they sob up and they tear up,” Steve said. “And they just say, ‘I can’t believe that Johnny’s not here.’”

Honoring John

Otterstad is one of the premier sports artists in the world. And baseball holds a special place in his heart, thanks in large part to his father.

“Dad’s love of history, Dad’s love of a great story and Dad’s love of baseball” led to a deep love of the game for Opie.

Otterstad knows and appreciates that each painting of his means something unique to whomever owns it.

And in the case of Steve Sax, Otterstad sees that principle shining through brilliantly.

“I just made a big painting, and someone saw a greater meaning in it than I had even intended,” he said. “And that speaks to the power of the work itself, that I have nothing to do with. It very much has a life of its own once it leaves me. It goes on to be its own thing.

“And for whatever reason, Steve walked in and saw that painting in a gallery full of people, and that painting struck him that way because of his memories and his history and his love for his son. And that’s amazing.”

Steve and Opie have collaborated to make the viewing experience of this work even more incredible than it already was in the gallery. With the digitized NFTs, you can hover over each Hall of Fame kid’s face and a link will appear to a video about his career.

And if you hover over Otterstad’s signature in the bottom-right corner, there’s a video explaining how “Babe and the Kids” came to be.

Those who purchase one of the NFTs have a stake in the future of the initiative.

“The NFT has what’s called a utility attached to it,” Steve said. “And that utility is that everybody who owns one, we’re going to become a team. And every year, we’re going to have an event where we all get together and everyone’s going to give their input on what we should do the next year to raise money for the foundation.”

In the end, all of it is for one overarching purpose, one that Steve said he hopes will “go on in perpetuity.”

“This is how we can honor my son,” Steve said. “And that is so important to me.”