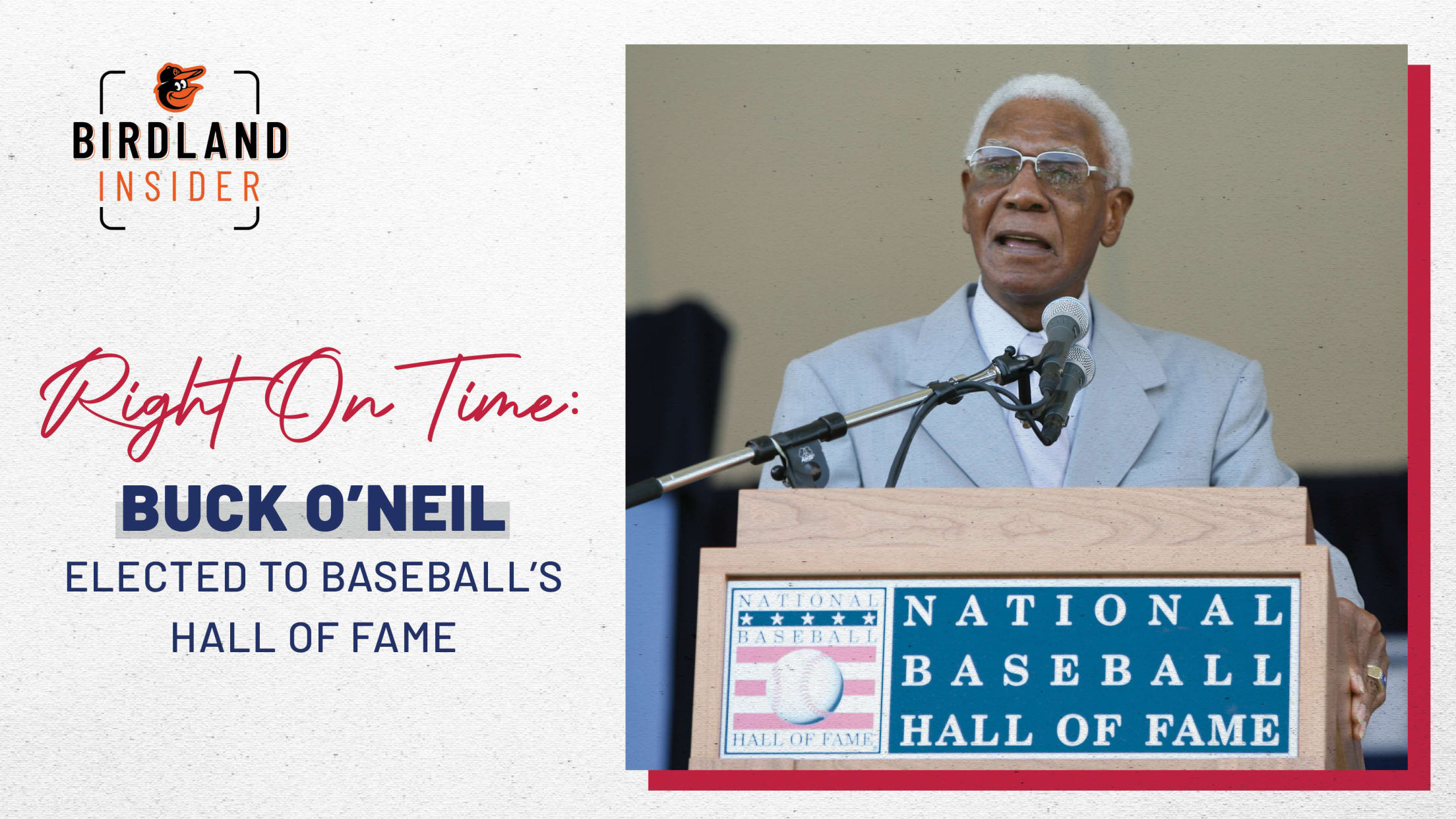

Buck O'Neil's Time Has Finally Come

There are those who think that Buck O'Neil's election to Baseball's Hall of Fame is long overdue.

If he was alive to revel in his being elected, there is little doubt what O'Neil's response would be.

"I was right on time," he would say -- as he did often when speaking about his seven decades in baseball.

After spending nearly two decades as a player and manager in the Negro Leagues, and more than 50 years as a coach and scout in the Major Leagues before his passing in 2006 at age 94, O’Neil never betrayed a hint of bitterness over being passed over for election to Baseball’s Hall of Fame.

“People ask me: How do you keep from being bitter? Man, bitterness will eat you up inside,” he once said.

You shouldn’t feel sad for a man who lived his dream. You know what I always say? I was right on time.

O'Neil began his career in the Negro Leagues, almost all of it with the Kansas City Monarchs. Except for two years he spent in the U.S. Navy during World War II, his official playing career was from 1937 to 1948, although he played and managed in the Negro Leagues through 1955. While with Kansas City, he had a role in managing and mentoring future big league stars Ernie Banks and Elston Howard.

When the Monarchs were sold in 1955, O'Neil became a scout for the Chicago Cubs, signing future Hall of Fame outfielder Lou Brock.

The Cubs made O'Neil the first Black coach in Major League history in 1962. Two years later, he returned to scouting and signed outfielders Oscar Gamble and Joe Carter and Hall of Fame reliever Lee Smith, among others. O'Neil remained with the Cubs until 1988, when he joined the Kansas City Royals as a scout. He was still scouting for the Royals when he passed away.

In 1990, O'Neil was instrumental in establishing the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City and served as its honorary chairman until his death. He delighted in keeping alive the memory of the Negro Leagues.

He served on the Hall of Fame’s Veterans Committee for 20 years, from 1981 to 2000, and had a hand in electing 11 of his Negro League colleagues. And it was O’Neil who, in 2006, spoke for the 17 Negro League players, managers and executives who were elected through a special Hall of Fame ballot – a ballot he was on, but came one vote shy of the requisite number needed for election.

He died less than six weeks after the 2006 induction ceremony.

There would be numerous other honors and awards for O’Neil. He was presented a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. Statues of him grace the entrance to both the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown and the Negro League Baseball Museum in Kansas City, and his bust is in the Missouri state house.

In 2008, baseball introduced the Buck O’Neil Lifetime Achievement Award, presented every three years to “an individual whose extraordinary efforts enhanced baseball’s positive impact on society, broadened the game’s appeal, and whose character, integrity and dignity are comparable to the qualities exhibited by O’Neil.”

In honor of what would have been his 100th birthday, the Orioles’ Minor League facility in Sarasota, Fla. – where O’Neil was raised – was renamed the Buck O’Neil Baseball Complex. In Kansas City, where he played, managed, and lived most of his adult life, a bridge crossing the Missouri River was renamed in his honor.

Induction into the Hall of Fame, however, appeared to have bypassed him. The Hall of Fame has a number of inductees whose candidacy rests on their overall contributions to the game, not their playing careers – pioneers like Henry Chadwick and A.G. Spalding. But now, 15 years after his death, after he helped open the doors to the Hall for many of his contemporaries, O’Neil is taking his place among the game’s legends. His on-field accomplishments and his off-field legacy have earned him a plaque in the Hall of Fame gallery.

The grandson of a slave, John Jordan O’Neill was born in the town of Carabelle in Florida’s panhandle November 13, 1911. He moved to Sarasota at age seven but was not allowed to attend Sarasota High School because of the color of his skin (he would be given an honorary diploma in 1995). He left Florida at 23 to play semi-pro baseball. Three years later, in 1937, he signed to play for the Memphis Red Sox of the new Negro American League, and the next spring was acquired by the Kansas City Monarchs.

Renowned as an excellent defensive first baseman, O’Neil spent the next 18 years with the Monarchs, except for 1944-45 when he was in the Navy. Because Negro League statistics are often incomplete, it is hard to get a full measure of O’Neil’s career. Baseball-Reference.com credits him with a .283 career average; the Seamheads Negro Leagues Database says .262, while the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum has O’Neil at .288.

He managed the Monarchs for eight years starting in 1948, winning two pennants, before joining the Cubs as a scout at the end of 1955.

While O’Neil was known and well respected within baseball circles for decades, it wasn’t until 1994, when he was featured in the Ken Burns’ documentary “Baseball,” that he became what he called “an overnight sensation at 82.” He had extolled the exploits of the Negro Leaguers he played with and against for years, and used the fame that came with the documentary to spread the stories to new audiences.

“Buck was one of the finest human beings who ever walked the face of this earth, who just happened to be a great baseball player,” said Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. “He demonstrated you could go farther in this life with love than with hate.”

In establishing the Buck O’Neil Lifetime Achievement Award – and naming O’Neil as its first recipient – Jane Forbes Clark, the chairman of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, said, “Buck touched every facet of baseball, and his impact was among the greatest the game has ever known. The Board recognizes the impact Buck had on millions of people, as he used baseball to teach lessons of life, love, and respect. His contributions to the game go well beyond the playing field.”

And now – finally – his contributions have been recognized.

Right on time, you might say.